By Adelina Gina

The fourth part

-“I cried for you like dead, I waited for you like alive”-

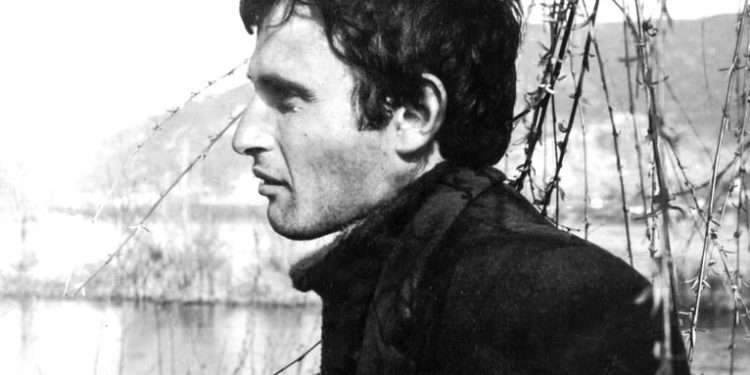

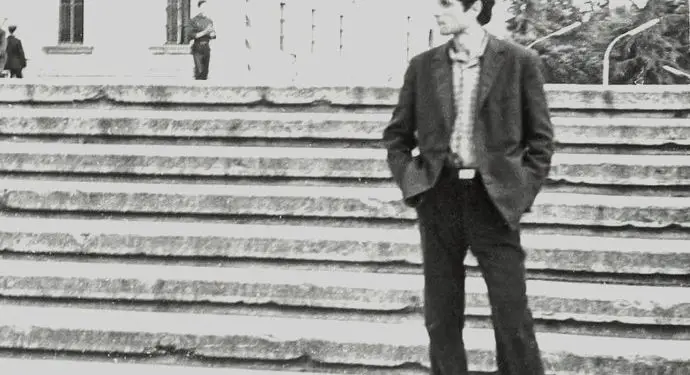

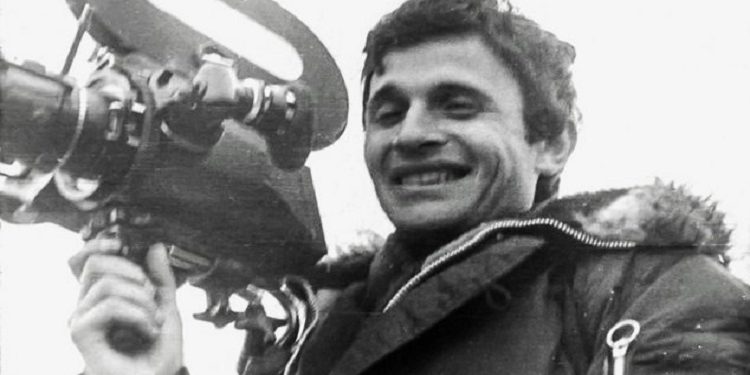

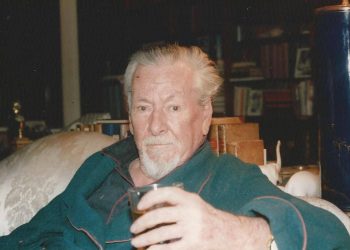

Memorie.al / Rescue Gina, graduated in Journalism at the University of Tirana, in 1974, playwright, screenwriter and librettist, in the early 70s, thanks to his extraordinary talent, his work, works and creativity, “shocked” the artistic institutions of Tirana, as; The People’s Theatre, the Opera and Ballet Theatre, the High Institute of Arts and the Albanian Radio-Television. He was one of the most sought-after chiefs and senior leaders of these institutions. In the time period 1971-1974, he left his mark, having collaborated closely with some of the most famous names of that time, such as: Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, Pirro Mani, Mario Ashiku, Zhani Ciko, Nikolla Zoraqi and director Mevlan Shanaj and operator Pali Kuke. But the traces he left in these cultural and artistic institutions were unfortunately lost in the official silence of the communist regime?! In August 1974, Shpëtim Gina, lost his life in unexplained circumstances, drowning in two feet of water, in the river Drojë of Mamurras, (where he was performing the military choir together with other students), two days before, he had put a lightning sheet to the Chief of the General Staff of the Army! Was it really an accidental death, or was Shpëtim Gina eliminated by the State Security?! Why his “friend” who was with him until the last moments, declares that; “The body that was taken in the ambulance, wasn’t it Rescue?! Or the doctor of the military department of students, Mark N., who says: “We immediately went to the scene, but we did not find the body of Spetimi”?! And his family, why insists that; “They didn’t allow us to open the coffin before the burial when they brought it home and years later, we opened the grave in ‘Stalin City’, to bring it to Tirana, where we had moved as a family, those bones were not of Salvation, as they were missing. ..”?! Many questions, which have not yet received an answer! His sister, Adelina Gina graduated in journalism in the late 60s, in a book of hers entitled; ‘Where did you take Salvation’, published in the USA.

I went to the festival in a purple sundress and a blouse with small purple, yellow and sky-blue checks. They fit me well. I had a seamstress friend who had been a ballerina in her youth. At the hotel, I stayed in a room with the well-known artist Vaçe Zela. She was from Lushnja and was friends with the Ginats, our father’s family. It was well known and everywhere we went we were greeted with shouts; “Vaçe, Vaçe”! We ate dinner in a flower garden, where there was music and dancing.

The evenings were cool. At the door of the flower garden, we always met Memtor Xhemal, the well-known opera artist. He sat with us at the table. “How come we meet you every night”?! I told him. He winked at me. “I stay and wait for you, because if you stay with Vače, you don’t pay. It doesn’t bother me, because I’m young”. We laughed and, as always, the dinner was prepaid by the admirers.

August also came. Sadija, with her children and Dritëroi, went on vacation to Shengjin. He ordered me to get a service and go there myself for a few days. I remember that it was the fourth of August, when I asked the editor-in-chief for a service to the Shengjin Pioneer Camp. I told him the truth, that on this occasion I want to meet my brother, who makes the choir in Mamurras, and at the same time, write a report about the camp. He agreed with me. I started that day.

During this time, I had never been, because I knew that Ana went to see him. Shengjin has a deep blue sea, the water is a bit cold, but I like it very much. I spent four days. Sadija kept me in her apartment. The building was two stories and close to the shore, they had a large room, a kitchen and a balcony. There were other artists who were resting there at that time.

I remember that near us, there was also Mario, one of Spetimi’s close friends, with his wife and sons. Salvation has a poem for Bland. It is titled “To Bland, My Friend’s Son.” The last line is: “I go out to kiss your cheeks, little dramatist”! He was connected with Mario Ashiku by his work with dramas, at that time he was a director and lecturer at the High Institute of Arts. I know that Shpetimi valued his friendship with him and loved him as a person. “He is noble,” he said, “he also has modesty, then he tries for new things on stage”!

The days were pleasant by the sea. I used to go to the children’s camp in the early hours, then swim, sunbathe with Sadija, Lona and Artan. Driteroi stayed on the balcony, rarely went to the beach and wrote. I would have philosophical discussions with Sadie and tell her that, being eleven years older, he had other desires and that this is a matter of generations. She laughed with me, she enjoyed it, she was young. At dinner we stood on the balcony and Dritëroi read us the new poem he was writing. I remember it was about the poem; “Mother Albania”

The sea is scary at night. I could only hear the sound of the wave, but I did not turn my head from him. I don’t want that night. In the morning, with the League’s car, the driver was a blond, silent boy, I left for Shpëtimi, in the choir. To go to the military ward, from the main highway, it does not take much. The door to the ward was barbed, there were two guards with guns and an officer standing at the entrance. I asked for Salvation. “You’re lucky, the student soldier told me, he’s in the hospital, he didn’t go to training. Wait, I’ll call him.” Salvation came a little later. We hugged tightly. “You’re not in training, you’re sick? Why are you hospitalized”?! He put his hand on my arm and we walked away from the guards.

“I’m not sick. It’s good that you came. You’re tanned. No, you don’t tan, I’d rather say you’re red, you’ve taken a bath.” “Why did they put you in the hospital”?! I interrupted him. “Listen, he said, I shocked the doctor. He laid on me in vain, he even told me, if you have a friend, bring them so you don’t get bored.” At that moment, it seemed to me that someone threw cold water on my back, I got goosebumps. “Be careful, I told him, when he starts talking, you open his heart, who knows what kind of person he is.” “Don’t be afraid, he told me. How can I speak to him, when he himself told me that he is part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs?! Do you understand now? Here is how I, a trainee doctor, conducts the military chorus”.

I don’t know, I had a doubt. Who was this man? And why was he doing all these violations, for Salvation? There was something wrong. The fact that my brother knew that he was a member of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, seemed to calm me down, because he would be discreet, however this closeness caused me some kind of fear. “Know me with him, I said to Shpeti, let’s go meet him.” “It’s not here today,” he told me. “Where did he go?” “They called him to Tirana, to give him some medicine for me”! “Medication for you?! I asked scared. Why what do you have”?!

“I have nothing” and laughed mysteriously. I don’t know, but in those moments, because I got the impression that they were talking about a medicine that men used, so it was something that my brother didn’t want to tell, and I didn’t ask him any longer. “You will come with me,” I said. “Yes, he said, here I come.” He hurried to the shed. He returned with some clothes in his hand. We got into the car and headed towards Tirana. On the way, he took off his military clothes and put on his civilian pants and shirt. We arrived in Tirana quickly. “Now you’re free, walk where you want, I’ll go to work, I’ll do the writing. We’ll meet at Vollga”. At “Rruga e Durres” we parted, I entered the newspaper, he walked along the road. I wrote the report about the Shengjin camp, handed it to the reporter, it was planned for the next issue and at 2:00 PM, I went out relieved to have lunch.

Salvation was waiting for me at the door of “Volga”. When we used to go there, he always liked a table, which fell from the side of the window, outside it was a flower garden with tables. In the evenings there was music and cold beer. “Take what you want, I told him, don’t look at the prices”. We had a good lunch. He had taste in the choice of dishes. We also bought wine, he rarely drank, he didn’t want to spoil it for me. After we had lunch, we went to the cafe where we ordered cakes. “We will buy pumpkin seeds with the remaining lek,” he told me.

Walking along the boulevard he said: “I wonder how you became so generous today, you spent a lot”?! I laughed. “Come on, take these lek, but don’t make them grapes and plums, rent left and right, because I don’t have that much money, then I don’t work for your friends”, and I handed him 500 ALL. Meanwhile we reached the train station. I went and booked him a ticket to Mamurras. “You are mad today,” he said. We hugged and he boarded the train.

I don’t know how it came to me, I don’t know what I thought, but I put my hands in front of my face and burst into tears, I didn’t want him to see me cry. I felt my shoulders fall and rise. He got off the train. The train was on its way. It hit me hard, “What’s wrong with you? Why are you crying?! But you didn’t cry when you made me a soldier. Today you remembered that you should cry?! Then yes, it was cute. But today it’s useless”?! I smiled through my tears. I hugged him tight, tight. He rode in haste. The train started. I waited until he left.

That day, since the newspaper came out the next day, they worked in the afternoon until late. I climbed the stairs of the newsroom, with torn legs. I sat down at my desk, put my head on my hands and cried. “So, what’s possible”, my office mate asked me, I continued to cry. “What do you have, man”?! And he shook me. “Nothing, I said. I don’t know, I’m crying. Leave me.” It was Thursday, August 8, 1974. A few days later, on August 14, Mira came to Tirana. The next day we would leave for vacation in Saranda. We went to the shops together, bought some things, and entered the cafe “Tirana”, which was frequented by artists.

At the entrance, we met a well-known writer with his wife, later she told me that I looked like a flower to him. We ate an ice cream and talked about vacations. With Mira, you always feel good. I was happy that Mira was separated from that home environment, from daily chores, from the small town and we were going to rest together. Father was happy when he found out that I would take Mira with me. “Don’t worry about us, Tito and I will both be fine. Mira has everything fixed here.”

The next day we took the half past nine train. Part of the route was by train, the rest by bus. The day was beautiful, with lots of sun. As soon as we left in the morning, it was hot. At this time, another train was leaving for Mamurras. Later, the secretary of the collegium revealed that that day, someone had asked him on the phone about me. It seems that the voice had been authoritative, because against its nature, this one, which was a little arrogant, had been forced to answer it accurately, that; “has left for vacation in Saranda”.

It was August 15. It was hot. The road was long and tiring. We didn’t eat, we only drank water. The bus made a few extra stops, because there were also children riding in the car, so we arrived late. It was nine o’clock in the evening when we arrived in Saranda. Our legs were numb. In addition to the man who had booked our room, he worked in the Pedagogical Cabinet and was an associate of the newspaper, we also saw several other men. What was this waiting?! They approached us. “Only the flowers were missing. What is this whole delegation”?! I said jokingly. They lowered their heads, apparently the joke didn’t take place.

We introduced ourselves to them, they were education and government workers in the district. Walking along the road, a petite woman approached us. She was the wife of one of them. “The room has not been arranged yet, come to me tonight, she said. We have room, you can arrange it tomorrow. It was late tonight”. I thanked him, but declined. They were unknown people and I was so tired that I wanted to lie down, I could barely stand. They didn’t bother, they gave me the keys and left. We were tired and lay down immediately.

Maybe from tiredness or changing the place, I couldn’t sleep. Even Mira tossed and turned in bed. There came a moment and he seemed to fall asleep, I didn’t move anymore, I was afraid of waking him up. In the stillness of the summer night, there was the rhythmic sound of the sea wave, coming, crashing and receding. Behind her was a sign, as if someone was crying. Another wave came with its noises, then the crying was heard. Mira woke up. “Who cries like that”?! she said. “I don’t know. I didn’t know that place and I knew that this crying came from the mill. “Sleep”, I told him. “Are you listening to him crying”?! she said. “Tomorrow we will look for another place, do you sleep now? There came a moment when I could no longer hear the wave, only the boat was full.

I may have slept a little, but when there was a knock on the door in the morning, I was up. It must have been six in the morning, because the sun had started to rise. An unknown woman informed me that someone wanted to talk to me. I got dressed and went out. He was a middle-aged man. He presented himself as the oil director. There was also oil research in Saranda. “You are Adelina, he addressed me, the eldest daughter”?! I nodded.

“Your father called me because he is sick”! “What’s the matter?”, I interrupted him. He thought for a moment: “One of his hands is paralyzed. If you want, the father said, if you want, you can stay.” “We’ll be back right now,” I said. “Can you help us find a car?” Goodbye and farewell to father”. He left.

Two years ago the mother had died, now the father with a paralyzed arm. How should I tell Mira?! I had to appear strong so that she would not be afraid, because she is like a sparrow bird, always looking for support. Even so, it is subtle, subtle. I opened the door of the room. She was waiting for me. “What? Why did you come out? Who was it”?! “Miroshe, father has announced that he is a little sick, how about we go back”? Without letting me continue, she squeezed me:

“Tell me the truth, he’s dead”?! “No, – I shouted louder, – for my mother’s soul, no, I won’t lie to you.” She sat on the bed and wiped her tears with the palm of her hand. I closed the suitcases, the spoils we had taken off, only our nightgowns. We went out into the street. We climbed some stone steps and, on the street, we saw a car. I recognized the license plate of Tirana. When I got closer, Çyli, the head of the administration of the Ministry of Education, appeared in front of me. The driver was sleeping on steering wheel. I told him how I was in trouble.

“Get in,” he said, “we’ll take you to Lushnje, then find another car.” On the way out of Gjirokastra, the car broke down, they were worried, they found a policeman, I don’t know what they told him, but the policeman found a mechanic and fixed the car. When we arrived in Tepelena, we were asked to eat something, or at least drink a coffee. We did not accept; nothing was wrong with us. Mira was crying slowly. “Father is dead,” he said. “No,” I said, “my heart doesn’t move.”

When we arrived in Lushnja, the driver told us: “I’m doing the honor until the end, I’m taking you home.” And continued on his way. “Gas” stopped in front of the house. The whole place in front of her, the road, the flower garden, the alley was filled with people, it seemed as if the whole city had been flooded. “After my father died,” I thought. “They came, they came,” voices were heard from the crowd. At the door of the house, the father came out, followed by Petrit. I dumbbells. “And why have they come?” I uttered in a low voice. Father took us both in his chest, the crowd fell silent.

I was not understanding anything. The uncle, nearby, said: “Salvation has died for us.” “Salvation…”?!, I said and the ground shook. I rushed into the house, I looked for him in all the rooms. They were full of women dressed in black, men, but he was not there. “No, it is,” I said. “It’s not true.” I didn’t cry or scream, I was stunned with my eyes fixed somewhere. I didn’t know a single person. According to custom, I had to dress in black. I came with a red and blue checkered dress I don’t even know today how they dressed me.

I had frozen. They were crying, screaming. “Don’t, rest, the father called. My daughter is running away”! The doctors screamed. As they told me later, there was a grave silence. I don’t know what they did to me, but some time passed and I noticed a white spot, I extended my hands in that direction and said: “He”. “He survived,” said the doctors. Everyone turned their eyes to “He”. It was Mevlan Shanaj, the director, his friend. He hugged me and for the first time, I cried on his shoulder. At that moment I understood what had happened.

They brought him late, at half past three. I didn’t kiss him. I had kissed my dead mother and from that moment, she was no longer my mother. No, I didn’t want to lose Salvation. Mira was crying loudly: “Oh my mother”! as if asking for help from her dead mother. Father did not cry. The night before, the news had spread in the city, he did not know anything, even she, the Italian, my mother’s friend, had gone home, his father had asked him for a coffee.

Nothing went wrong with her. He had stayed for a while and left. The father’s people, who lived in Lushnje, had been notified. They arrived at night. Silence everywhere. Father and Petrit were sleeping. They were sitting in the yard and had waited for it to come. They let him sleep for a few hours. In the morning there was a knock on the door, the father opened it in surprise. The brother, the one from the war, said: “Salvation died for us”. The father only stuttered: “Take off my pajamas”.

His brother took them off and put on his pants and shirt. No tears were shed, this was not death, this was beyond death, all bounds of feeling had been crossed. They opened the coffin. He was wearing a military uniform. They discovered only the upper part, from the middle to the top. His hands were covered with a red cloth, his hat was pulled up to his eyebrows. He seemed young to me, like an eighteen-year-old, and healthy, without the sharpness of his features. The eyes were closed, they seemed big, the lips were full, as they had been.

The thought popped into my head; why the dog looked as if with paints, as if every feature was drawn, colored. They left him there for only half an hour. In that room, where only women stay, there was also a man, a civilian. As they told me later, when our people wanted to dress him in a costume, that civilian refused, even, as my aunt’s daughter says, when she reached out to touch Shpetim’s hand, the civilian pulled her so hard that she had cried out in pain. That unknown civilian did not leave the room for a moment.

The commander, Agimi, who had come along with some student soldiers, did not know the civilian. A cousin of ours, a short, intelligent man, whom Shpetivan and I called “Kerenskina”, because he wore a coat like that of the time of the Russian Tsar, said to the civilian: “The civil state does not give permission for burial without the cause of death”. The civilian pursed his lips and took out a letter from his pocket.

“Us,” he said, “mechanical asphyxiation, drowning in water.” Then he took out two pens and some money from his pocket. “These were found in his military clothes, when he was washing.” “Kerenskina” mischievously asked for the cause of death, because a little while ago, the desperate uncle had said: “They have killed our Salvation.” “What is this nonsense,” replied the father, “who killed us?! Hold on, you’re desperate and you don’t know what you’re talking about”?! /Memorie.al