By Kristale Ivezaj Rama

The first part

Memorie.al / “I was born in a prison in Shkodër and after two weeks, we were interned as a family in Berat. Finding pleasure in seeing others suffer, especially children! Man, then, begins to suspect these people who have nothing in common with man, except the name man”.

Mr. Simon, first of all, who are you and what was the reason for your isolation in special camps by the communist regime, right after the war?

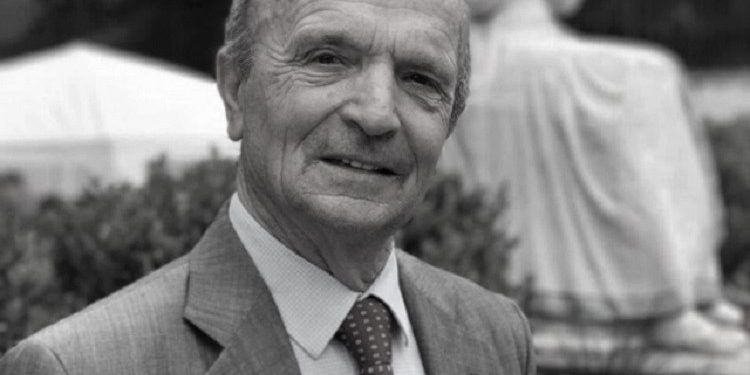

My name is Simon Mirakaj. I was born on June 7, 1945. I was born in a prison in Shkoder, because many houses in Shkoder had turned into prisons: The owners of the house had either been shot and their families had been exiled, or they had been put in prisons. This tragedy happened among the best families of Shkodra. I was born there, in one of these houses. They say, to a family named Vuksanaj, who owned the house then. After two weeks we were interned in Berat.

I mean, you were a newborn, a baby just two weeks old?

Just two weeks, and the reason for our displacement and isolation was the family’s anti-communist stance. My father, Pal Bib Mirakaj, had two brothers. He himself was the youngest. The eldest of the brothers, Col. Biba, was a minister at the time of Italy, Minister of Internal Affairs. The other aunt, aunt Pashuk, together with her father and her nephew who had come from studies – he was in the third year of studies in Italy for engineering, – went up the mountain, together with others.

What time is it about?

Father together with his followers stayed in the mountains from 1944-1951, in the mountains of Puka, in the area of Mirdita, Tropoja.

Your brother told us that he found a diary of your father, Paul Bib Miraka.

Yes, that’s how it is. Baba kept a diary while he was on the mountain. His brother, older than his father, was killed there. His nephew, 29 years old, married with two children, was also killed. However, the father continued the resistance against the communists together with his followers.

What happened to him, how did the resistance continue?

In 1951, since our country’s friendly relations with Yugoslavia were severed, they hoped for some anti-communist help in Yugoslavia, so they crossed the border. There they were put in a camp in Podujevo.

So the father escaped?

He escaped. Father was in the mountains, for this reason, we were moved from Shkodra and isolated in Berat. In 1949, when relations with Yugoslavia were broken, we were sent to the Turhan camp, where 30 children died within 24 hours. Turhani, if you have the idea of Tepelena, is on a hill in front of the camp, on the right side. There they put us through the cattle stables. Those children died from lack of hygiene, food and adequate shelter.

Did you later learn how your mother managed to feed you, baby, in those conditions where there was a lot missing?

No I do not know. God has fed us more than mother. That even mother had nothing to feed us. Only 300-400 grams of bread was given there.

What was your late mother’s name?

The mother’s last name is Kune. Catholics have two or three names. Kune and Sofie, but we know her by the name Kune. They landed us in Tepelena and the tragedy continued. After Stalin’s death, the Tepelena camp was destroyed.

How old were you when they took you to Tepelena?

How many siblings did you have? We were two brothers and a sister. The sister, Adelajde, was 9 years old, a little older than us. He passed away two years ago. The biggest burden fell on her. At the age of 14, he was separated from us; this happened to other girls as well. They took them to Tirana, to Kamëz, to the Brick Factory, a terribly hard job for that age, especially for girls.

Still a child. What did he do there?

Physical work, brick cutting. You have no idea how hard work it was. Today there are modern brick factories, but back then, they cooked clay mud for bricks, a terrible, very heavy job. After the clay was cooked, a brick-shaped box split down the middle was filled with clay. A little sand was thrown so that it wouldn’t stick to the boxes, after they were taken out of the boxes they were put to dry and after drying they were baked. And it was used for the wall, and for everything.

You, what work did you do?

We were small in Tepelena. However, on Sundays, we worked with war munitions left over from the war. Tepelena was filled with war bombs; there were shells on the ground and under it. The most dangerous were those that were just below the surface, because they caused tragedies. The women put the kettles to boil the clothes and the children came near the fire to warm themselves. There have been many cases where many children have died from the mines that were under the boiling cauldron. They were torn to pieces. We were taken for those that were above the surface, we stacked them as wood is stacked.

Where did you store the bombs?

Inside the wires. While the girls and boys who had finished the seventh grade, they were taken to work, accompanied by soldiers with machine guns. They carried stones up the mountain; they carried manure for the command. To come to the camp they had to cross a footbridge, those are the bridges that shake. A group of girls, tired and desperate, decided as soon as they arrived at that bridge, to jump into the river, to end their lives. He had come this far. There was also an older person with them.

She was Italian, as far as I remember, married to Mustafa Kruja’s son. Her husband was in prison and she had come to Tepelena with her son. She was a professor, she graduated from Bologna for literature, and she says to these girls: If you jump, of course you will end your life yourself, it is your choice, but do you understand what pain you cause your mothers? Then the girls stopped, looked at each other and did not jump into the river, but continued on their way.

The Tepelena camp has been compared to Auschwitz. It cannot be imagined by anyone. Even I, who lived there myself, today, it seems to me as if I am telling a novel, a short story. So incredible was the animalistic behavior of those people: Finding pleasure in seeing others suffer, especially children. Man, then, begins to suspect these people who have nothing in common with man, except the name man. In 1954, after Stalin’s death, we were removed from the Tepelena camp. It was closed and we were brought to Lushnje. Lushnja was an agricultural country.

How old were you?

I was 9 years old. I did my first and second grade in Tepelena. It was very difficult because the way to go to school was a little uphill, we climbed the hill. We were without food, without breakfast.

Can you tell us a little about your school experience, how was it? Did all the children go?

All children who turned 6 years old started first grade.

Were you forced?

No, it was announced by the Ministry of the Interior, through the command that we had in the camp, the police command that the children who have reached the age of 6, get out of the wires and go to school. And we went and enrolled in school. Someone had finished the second or third grade. Someone started over like I did. At school we did not have any differentiation with others. They were also smokers.

They didn’t look down on us. They were children just like us, while the teachers were. Teachers made the difference. I have had a case of my own. I was in first grade. The lesson was ending, the teacher caught me: Stop! I thought now that there is no good news. And he says: Do you love your father? I had not even seen my father, because when I was born, he was in the mountains. And I say: I love him! Instinctively. How do you want it? – said. She took the ruler and shot me with its blade.

Was it male or female?

Man.

How did you react afterwards?

Like the child who always does the opposite of what he is told. He kept shooting me, I kept telling him “I love him”. He kept falling for me. I started to cry. However, behind the door was the brother. He was in second grade. He started crying too, because he heard that I was crying. He was with his sister, she was about 10 years old. After half an hour, the teacher let me go and we headed towards the camp. As soon as we passed and took the road that was a little lower, I fainted. My brother and sister took me by the side and when I went to the camp, I came to my senses.

Can you describe the teacher? What did it look like?

It’s been many years, to tell you the truth. He was a young man, about 20 years old. I don’t know if he had finished school or not. That at that time you had 4th grade school, it is enough to have partisanship.

What did he teach you?

Primer.

Even for the party?

No, I don’t remember. Maybe the third and fourth grades could have some rhymes for the party. Of course, they, the teachers, also did the party’s propaganda work.

Also, were you afraid of the teacher? How was the figure of the teacher built in your consciousness, because it is known that it is a very important compass in the life of every child?

Of course, when I saw it, I saw it with fear that the same story is continuing, but it didn’t happen again. Only that day. Imagine, now, how much that behavior of his is embedded, that even after 60 years, I remember it. As I said in 1954, we were removed from Tepelena. They sent us to Lushnje. Lushnja was an agricultural place, there were swamps, it had to be drained, and no one could do this work more than the internees could: opening canals, various jobs.

How old were you?

I was 9 years old, but I did not work. I continued school; I had just entered the third grade. We continued school in Savër. Savra was the camp where we first stabilized. Many of the internees who came from Tepelena were dispersed among the camps. We in Savër, another part in Plug, were distributed according to the need for work. But the situation had already changed a little, you worked, certainly hard work, but you were rewarded for that work.

How old were you when you first worked?

For the first time I worked at the age of 20. I just finished high school. When I finished the 7th year, we were given the opportunity to continue high school. We always appeared in the morning before the police, and during this time interval, breakfast and dinner, we appeared again on appeal before the police. They gave us the opportunity to continue school. So, that class war had not intensified much. In this period we were connected with the Russians and there was certain liberalism.

It can be called as our most successful days, compared to later years, because we were given the opportunity to finish high school. At that time there were also translations by various classical writers, Russian, English or American. During school, we were also engaged in reading and after school after we finished high school. Every evil has a good, whether in prison or in the camp, there were great people who kept us close and fed us with love for knowledge, for reading, because it is the best food to endure suffering.

Where did you find the clothes?

Yes, as I said, the class war had not intensified. We were bothered by our father. The father fled in 1960, fled Italy and went to America. During this period, he used to send us a package.

Where did your father get the information about your whereabouts? How were the packages?

We used to send letters.

Where did you find out your father’s address?

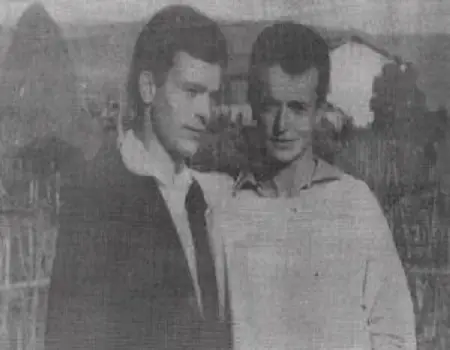

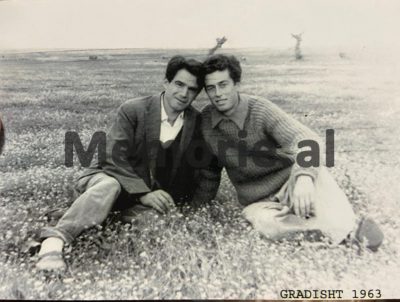

Look, through letters. Father was the first to bring us letters and photographs from Podujeva. Then, based on that address, we also replied and sent our photos. Then he again wrote us a letter that was sent by Podujeva. He was given the opportunity to go to Italy. In Italy, he had a brother, Kola, Col. Bib Mirakaj.

He joined his brother and then in 1960, because he didn’t stay in Italy, so in 1960 he left for America in New York. The father wrote on a typewriter and did not write with his own name, he wrote with a woman’s name. With the name Dalina. But he always put his signature. So we spoke very rarely. He could send us a letter once a year. They didn’t even give us the letter; they didn’t even give us the letters he sent. So…!

What were you writing about?

He wrote 3-4 lines enough for us to understand that he was alive. When we sent them the pictures, he said “I got them”. Even, when my brother got married young, 21 years old, because there you married young with the stupidity of the young, so, he got married young, and we wrote a letter to my father, and my wife Vali is pregnant. Back then, there were no devices to know if it was going to be a boy or a girl? He sends us 3-4 lines and says: if a boy is born, you will name him, if possible, Filip, Rrok or Leon. Sokoli goes to the civil registry, and they do not accept any of these names.

Why?

Because they had their own names. They had their own names and a name they had there will come. And luckily there was the name Luan. Leon – Luan, that’s how Luan recorded it. But we called Leo, for dad’s sake. We still talk to Leo today. In 1966, the correspondence was stopped.

Remember any lines from the letters?

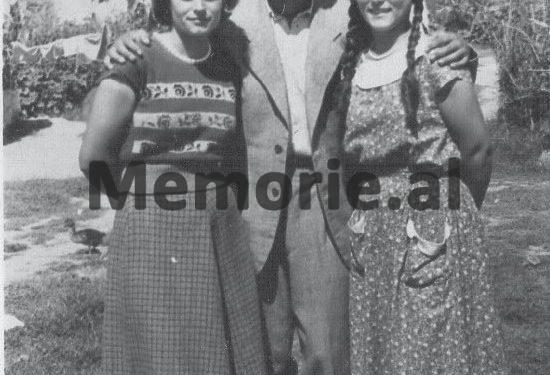

I remember. We sent him a picture of Vilma. Vilma was 3 years old, she raised her hands from the sky and he tells us: “I was happy with the photograph. Vilma’s hands seemed to me as if she was praying to God”. That he had lifted them up.

What about the pictures where you took them, because you were in exile, in the village? Or did photographers come from the city?

Yes Yes. They came from the city. Savra with the city was 4 km. They were private. They came often, because Savra was with families who wanted to have memories, either from work or from life. They often did. Every time they came, you could see almost all of them getting changed, cleaning up, and these photos were sent to the families who had them outside or inside. Father had sent us a picture with 4-5 other people.

But the father was without hair, like my business. The rest of them were all hairy, and I say to mother, how did you get this wax? And we wrote him a letter and he says, so, so. Simon saw the picture, – he tells him, – and says how you got this hairless hair. And the father says: “When I read Simon’s letter, I laughed with tears.”

Did you know, personally, any photographers of that time?

I don’t know if they are alive or not. I believe they are dead, because at that time they were. I remember the name of the woman who came to take pictures of us. She was a city photographer. His name was Fajka. From the first photographs of the city of Lushnja. Husband and wife photographers.

When you turned 20 and started working for the first time, what kind of work did you do?

The work was very painful, the first day. After I made the appeal, the first day, the next appeal began to get the work plan where you will work. These were called brigadiers. I even go to the brigadier and tell him, I am so-and-so, I present the documents. He tells me, you will work in the channel, there is no other job. Yes, where is this channel? The canal was by the road. However, think about it, a 19-year-old boy… what impressed you was not the work, but the problem was that, I said, my classmates will pass by and see me working there.

The canal I went to, I could see all the workers, the canal was 3-4 meters deep. With boots, because there was also water. I had no idea about the job. I had to clean up, throw the soil up. However, there was a worker who was nearby. He was older, had work experience and came to tell me how I should work. Straw hats were used there to prevent the sun from catching you. We made them ourselves. He had made us sisters out of a hat.

Did you have tools?

Yes, the shovel. I had put the hat on my head to disguise myself, as for the sun…! Then we started becoming professionals too, how to work every day.

How were your working hours?

Schedule, work started at 7 o’clock. In the summer there was no schedule, we stayed until 8 o’clock. But we had the police schedule, so we took advantage of this opportunity. We broke up. There were times when we worked from 7 to 9, depending on the job. We were forced to quit our jobs.

Was there a watch over your head?

Overhead guard no, stated, no. But they were all, they were undeclared. We were guarded by everyone. For lunch we had bread, summer greens, tomatoes, cucumbers, some cheese. In winter, a large jar, some yogurt.

How was the work during the winter in Savër?

The winter was a difficult winter. It didn’t snow, but rain, wind. Even in the rain we were forced to work. If you didn’t work a day, it was a lack of income. We were forced to wait for the rain to stop before we could take the day off.

What was the work quota, what was the rate?

The jobs were different. For example, there was plowing, opening of canals, there was corn irrigation, and not all of them had the same payment and rate. For example, to open a channel, the ribs had to be shaken well, 14 cubic meters was the norm. It was extremely difficult, but you had to, because if you didn’t do the norm, the income was less. Even in the rain we were forced to work. If you didn’t work a day, it was an absence. We were forced to wait for the rain to stop before we could take the day off.

Were you physically able to cope with the work?

It took time to recover. However, there was a good one; we faced it with the age of youth. We faced it because we saw old people dragging themselves. However, we tried to help them, but they had to do our norm. We helped them when we were near them.

How many years did you work there?

From 1965 to 1990, 25 years in the shovel. But the most difficult years were in 1969 when we were removed from Savra and sent to a 20 km sector away from Lushnja. They isolated us there. We were not allowed to move, only within the acres of designated land. In fact, when the State Security came to present us to the head of the Sector, they put us in a room and the one who appealed to us said to the operative chief who had come from the Internal Branch of Lushnja: How far do these people have the right to move?

And he expressly tells them that: “They have the right to move 700 hectares of land. They crossed the border, the bullet in the forehead”! They have been terrible years. We used to go there three times a day. If a foreign delegation came to Tirana, I remember from Cambodia, we were also appealed to 3 times a day there. Or, if Enver Hoxha passed by on his way to Vlora, when the holidays of November, New Year, May 1, etc. came, we were called 3 times a day.

I was passionate about football and in my youth I played very well. At least that’s what others who have seen me say. And when we were in Savër, we went to see “Tractor”, that’s what the Lushnja team was called. However, when they removed us from Lushnja, we were isolated there and there was no more. 15 years without watching sports.

The operative had arrived. We made the morning appeal and I told my brother, I’m going to ask him for permission, since Shkodra had come to play with Lushnja. And I was a fan of Shkodra and Lushnja. My brother tells me: “Don’t go, because there is no permission to give.” I’ll go, I told him, because I’m lost, I’ll go try it. I’m leaving. He saw me walking towards him and stopped. When I arrived there, I greeted him, – Mr. Captain. – “I’m not God, I’m a friend”, he said angrily. I tell him, – you are a friend, but you are not my friend. And here the provocation began. If I told him that you are my friend, then there were other things to do.

-“Why did you come”? – He told me, but in an animalistic way, with contempt. – I came to ask permission, to go to Lushnje to watch sports. – “Who plays”? – He said. – Yes, “Vllaznia” has arrived and will play in Lushnja. – “Why are you a fan of who?” – I – I told him – am a fan of Lushnja because I live in Lushnja, but I am also a fan of “Vllaznina” because I am from the north.

– “Why aren’t you with “Dinamon” – he said not without provocation? (“Dinamo” was the team of the Ministry of the Interior). I tell him that I am not with “Dinamon” and I will never be. – “Then, you don’t even have to go to watch sports” he replied angrily! I come back, I go home. We, in such cases, had to be determined, because if you were a little wobbly, you opened yourself up…! Memorie.al

The next issue follows