Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by the famous German historian and albanologist, Johan George von Han, who after many years of research, in his book entitled “Albania now a hundred years”, has reflected in detail and details the whole economic and political situation of Albania, from the second half of the XVIII century and ten decades later. From that book, parts of which were first published in 1943 by the periodical magazine “Leka” published in Tirana, we have selected some chapters, which we are publishing below in this article, adapting them to today’s language.

Although it was located at the far end of the Ottoman Empire, and one of its most backward and underdeveloped countries for more than 500 years, its own Geo-political and strategic position at the crossroads of trade routes. , its ports and harbors in water spaces from north to south, numerous mineral resources, handicrafts, orchards, fruit-culture, agriculture, livestock, etc., Albania was and remains a country that was constantly of interest to foreigners. This, among other things, is best seen in a study by the famous German historian and albanologist, Johan George von Han, who after many years of research, in his book entitled “Albania now a hundred years “, Has reflected in detail and detail the entire economic and political situation in Albania, since the second half of the XVIII century and ten decades later. From that book, parts of which were first published in 1943 by the periodical magazine “Leka” that was published in Tirana, Memorie.al has selected some chapters, which we are publishing below in this article, trying to adapt them in today’s literary language.

German Albanologist Johan George von Han: Exports of Cereals and Leather

It seems appropriate to supplement this writing with some remarks on the main export items we have mentioned above. The export of corn and other agricultural products could be greater if the reforms with the Tanzimat legislation and the signed treaties were fully implemented, which would ensure the commercial freedom of every citizen. On the contrary, the export of grain was often blocked, which came from the opposition of the rulers and their interests. Of great importance was the export of leather. The skins of foxes, thieves, and squirrels, to be further processed, were sent to Bosnia and from there to Shkodra and other places in Rumelia (the part of Turkey that lies on the European continent, our note), according to their needs. those places. The restriction on the export of cow, goat and ram skins depended on their use for opinga and other needs of the importing countries. Several factories in Prizren, Peja, Gjakova, Skopje, Ohrid, Bitola and Shkodra were set up and operated to process the skins.

Olive oil and fish hunting

Olive oil from the Ulcinj and Bar counties was exported to Austria, while the oil produced in Lezha all went to Albania for the needs of the country. Fishing was a monopoly right of the government, which gave the right to any entrepreneur, who had to pay 100,000 piastres (banknotes of the time), per year. Annual production exceeded the needs of the country and so it was transported to other nearby provinces. Likewise, the hunting of saragas (sardines, our note) was a common dish of the Catholic population for the holidays. On dark autumn nights, villagers living on the lake shore lit large fires. This was done with the aim of attracting to the shore the herds of sardines that came in bulk to some special places set up especially by fishermen, who then with their nets caught them without difficulty. The annual production of sardines went to about 2 to 3000 ounces, which in addition to a small amount, were all exported to Dalmatia and Italy. While the amount that remained for the needs of the country, was sold in Shkodra and its surroundings with ½ grosh oka. The sardine-rich country was the coast of Montenegro, so sardine hunting was one of Vladika’s most lucrative and lucrative activities. Even during the wars between Istanbul and Montenegro, when killings, arson, looting and the horrors of war prevailed, the shores of the lake enjoyed great tranquility. Both Albanians and Montenegrins fished together and shared the profits as brothers. Qefulli was mostly found not only in Lake Shkodra, but also in other smaller lakes located on the right and left sides of the Buna and it was sold for up to 1 grosh oka. Puppies (sardines) of mulberry were dried in the sun and then exported to Istanbul and Venice. The best ones were the ones caught in October, while the ones caught in the summer were bigger but less delicious. Eels also came in large numbers from the sea, especially in the autumn. Their fishing was done by settling on the Buna River (near the bridge near the bazaar), several rows of huts, set at a sharp 30-degree angle, from the sea. The wings of the baskets were closed, and as the water passed, the eels got stuck inside the net or sack that the fishermen put on top of the baskets. In this way the eels that wanted to get out of the lake towards the sea, fell into those bask.

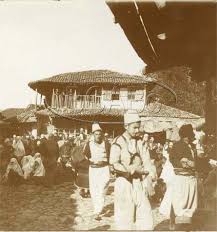

Silk market in Shkodra

Shkodra was once a good market for silk, even among the best of Rumelia, but around 1830 it suffered a major decline, which came as a result of the great competition made by the factories of Thessaloniki and some firms. French merchants operating in Edrene (Adrianopuli). Around 1845, a large amount of silk was brought to Shkodra from Filipopoli, Ternovo, and especially from the Edirne fair, which was worked either in the houses of the people of Shkodra, or in the 200 small factories that flourished at that time in that city. These factories, the population of the Muslim faith kept them as a monopoly of them, and the population of the Catholic faith was excluded from that kind of industrial activity, although the Tanzimat reforms allowed them to do so. This had caused great harm to the Catholics, as the use of silk and its sale was widespread. At that time, not only the rich or aristocrats, but also the middle classes of the population of Shkodra, used silk items a lot, such as shirts, napkins, bed and tablecloths, etc., and a large amount of these items. it was also exported to Bosnia, Dalmatia, Trieste, Venice, etc.

Exports of timber to France and Spain

Of great importance at that time was the export of cashews, wood which was found and collected especially in the area of Mirdita. Later, about 100-15,000,000 ounces a year were sent to Shengjin, to be exported to France (Marseille and Nice), Spain (Barcelona), where it was processed into powder and used to make various paints. The price of that type of wood was 3 ounces, while its leaves were sold much more expensively, reaching up to 12 ounces. This was because the leaves of the cashew tree had a coloring property many times greater than the stem of the tree. In ancient times, large quantities of timber for heating and construction were exported to Malta and Tunisia. But this kind of trade was then stopped for various reasons that came from the politics of these states.

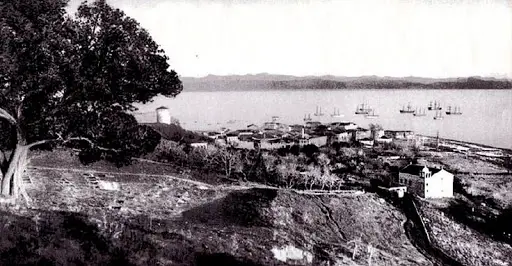

Maritime trade of Northern Albania

In the maritime trade that took place in Northern Albania, the main part was occupied by the people of Ulcinj, who had practiced this type of trade since ancient times under Turkey. Which made them the horror of the Adriatic and their actions had caused great resentment to the viziers of Istanbul and Shkodra. For this reason, Istanbul had ordered the destruction of the Ulcinj fleet several times, but it always failed, as in the last moments a counter-order arrived, canceling the first one. But one day, Sulejman Pasha, a declared enemy of the people of Ulcinj, as soon as he took command of the High Gate of Istanbul, acted with great speed, burning and destroying the entire fleet of Ulcinj found in Valdanoz Bay. Some time later, sometime in 1830, the people of Ulcinj were able to rebuild and regain their fleet, making that in 1845 they had about 53 small units, with 14 brigades, 12 trabakuj, 20 fëllunga (types of ships and boats) and 7 other boats, which were all built by the people of Ulcinj themselves. Most of the ships and boats that the people of Ulcinj had were dealing with the transport of salt and another part (with completely Albanian personnel) was dealing with the transport of passengers from Ulcinj on the line Shkodra-Trieste, Shkodra-Venice and vice versa. This made the Ulcinj fleet a great competitor to the Austrian merchant fleet. All this creates a great surprise, considering that the Albanian, who far from his homeland, on the warships and merchant ships of Turkey or Egypt, proved to be a skilled and very brave sailor, like Hydriot and Speciot, the heart of the Greek fleet, in its homeland, seems to have nothing but a sea of apathy and great coldness.

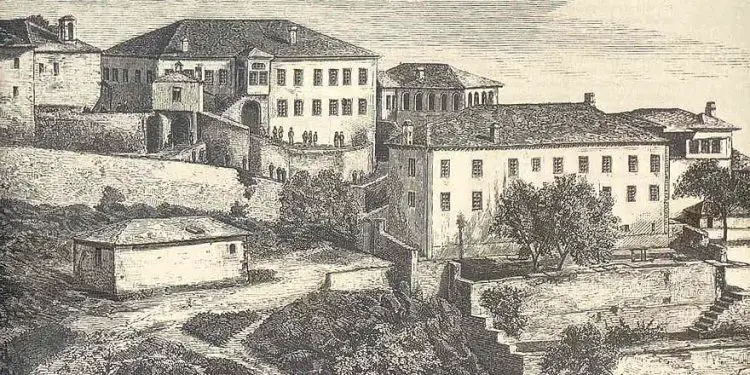

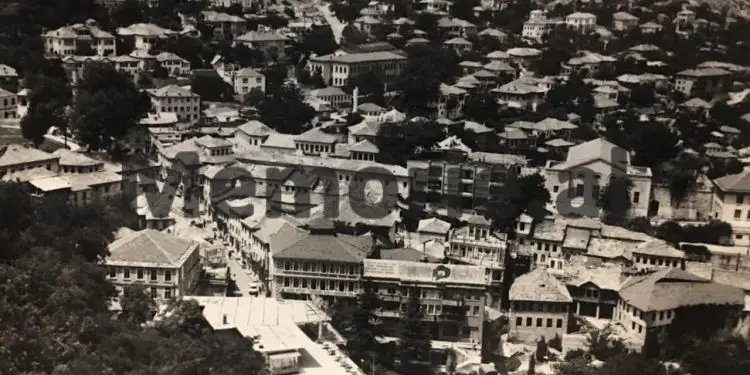

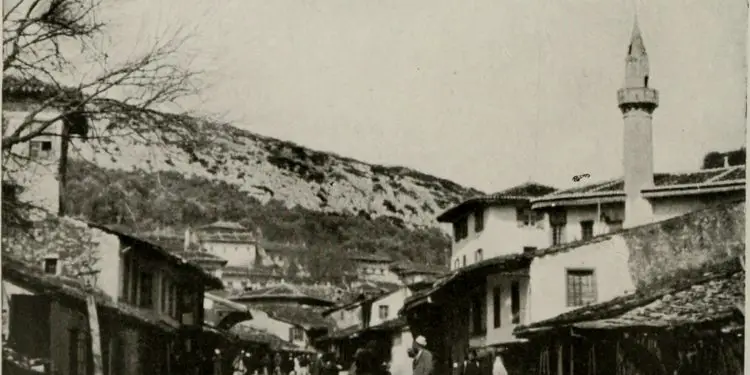

Ethnic Albania, Gjirokastra

The province of Gjirokastra is one of the most interesting and most populous in Albania. Its population, in terms of religious beliefs, is divided into Orthodox and Muslim. Orthodox are found in the villages and hamlets of Lunxheria and Rrëza, while Muslims are found in Nepravishtë, Kardhiq and Kurvelesh. It also has a mixed Muslim and Orthodox population, which is found in Gjirokastra and Labova. The owners of the lands of the villages of that whole province live in Gjirokastra. Their houses are tall and strong buildings. Among the lower floors they have no windows, but only a few turrets. The opposite happens with the higher floors, which are equipped with large windows and bring light and liveliness inside them. Their courtyards are surrounded and protected by high walls and secure doors, which lead the visitor to a small courtyard, from where the owners of the house from their turrets watch and control everything. The gate or other door can be opened by the owners of the house, only after they are sure who are the friends and the purpose of their visit, and then from the yard they can enter the house. The style of these buildings is more or less the same as those of the castles, owned by the aristocratic strata of Western Europe in the Middle Ages. Even the lives of their inhabitants are no different from those of medieval knights. Each lord used his income to keep as many servants as possible and to go to war with them when the Sultan sent word to him, or to enter the service of a Pasha or other official of the Ottoman Empire. . In difficult times, when the city was divided into different groups fighting each other (which was almost common), each gentleman, locked in his own house, tried with a rifle and gunpowder, and by any other means. , to harm his opponents. But since even this one was well kept in its own home, these wars were usually not very bloody. Here and there the peasants were given even after the plunder, but this happened to the little peasants, and when they hoped for a great and secret gain it was much less than the former generosity of the Western aristocracy.

The aristocracy of Gjirokastra, like that of the West

The Albanian aristocracy, on the contrary, in addition to the war, also dealt heavily with the payment of taxes and tithes of monopolies. It was like an industry, a monopoly of our (Western) aristocracy, which they (the Gjirokastra people) carried out with great and indescribable zeal. For this, real societies were set up that naturally reflected the political spirit of their members, causing harmful and dangerous competition in this area as well. The people lived in the service of the aristocracy, as soldiers or tax collectors, or by giving in to livestock, agriculture, trade, or handicrafts. Muslims usually entered the service of the aristocratic class, while Christians engaged in other work. Thus, the population of Libohova and Nepravishta, as well as that of the eastern side of the Gjirokastra valley, was closely connected with the faith, customs and political groupings of the aristocracy of the city of Gjirokastra. The Muslim population of Kardhiq, as well as the Christian population of Hormova, already a well-known name after the cruel atrocities of Ali Pasha Tepelena, derive their livelihood entirely from the military service they perform, as do the population of Himara and Zagoria. The population of Kurvelesh, which is entirely Muslim, deals with livestock and agriculture, but barely makes a living, as the land is not very fertile, which means that it produces bread only for 8 months a year, and over the years. worst, only for 4 months. A characteristic feature is the population of mixed faiths, which is spread over nine villages of Lungeria.

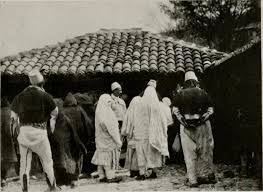

Gjirokastra men and boys in emigration

Since the land is not fertile, men leave it under the care of women and the elderly, and they themselves go to work in emigration, where in most cases working as gardeners in Istanbul. This is also the case with 11 Christian villages in Rrëza. There, too, men leave elders and wives to care for their families and lands, and they themselves go to work in exile. While two villages specialize in plumbing, making it possible for them to work on the construction of Istanbul’s waterworks in the old days, with special orders from the Sultan. The men of other villages specialized especially as traveling cloth merchants. Usually this craft of the men of the villages of Gjirokastra was followed by their sons, but this did not always work. In some families, the profession of folk doctor was inherited, which is widespread in other parts of Albania and the East. The temporary relocation of Gjirokastra men and boys to emigration has also occurred in other surrounding provinces. The men of Zagoria and Himara went as far away from Albania as soldiers, while the men of Delvina as farmers and gardeners. Thus, the residents of the villages to the east of the city of Ioannina are ready to have all the bakers, merchants, drinkers, doctors and tax collectors walking. In European Turkey, in Greece and in Asia Minor, there is no center of great importance for not having a small colony of Albanian artisans. More than 6,000 Albanian workers are found in Istanbul and other districts alone.

Immigration of Dibra and colonial masters

Of particular interest is the relocation of Dibran and colonists. It is not a displacement of a few, but organized, displacement that included all the men of the country. As it is known, the characteristic profession of the people of Dibra is construction. Dibrans are born masons. So it is today, so it was a hundred years ago. The buildings that were erected, the forests that were expected, the planks and beams that were being prepared for the Balkans, everything was almost without exception the fruit of the work and tireless activity of the Albanians. The excellent example of the labor force and the flourishing of Albanian relations was the fact that the people of Dibra joined the society and under the leadership of a master, were distributed in different places where the work of their craftsmanship was required. The departure usually took place on St. Demetrius’ Day (October 8), and they returned on St. George’s Day (April 23) because they believed that in order to be healthy, the summer season had to be spent in the fresh, fresh mountains. And perhaps they had reason to do so, as the countries of Greece, Thessaly, and Macedonia where they would work were often times malarial and extremely dangerous to their health. Regularly, except in special cases, they worked one year in one country and one year in another. For this reason, the master from Dibra used to visit the jobs offered to them, make the relevant contracts as needed, so that each group of them was safe to work for the whole year in the same place. Merchants and artisans did not leave and did not return home at a certain time, like the masons mentioned, but earlier and later, more often under the circumstances presented to them. Some of them stayed outside Albania for many years, never returning to their homes, as in the case of a merchant from Zagoria who left just a few days after his marriage, and returned home only after 12 years.

Southern Albanians, calm people

Southern Albanians are generally calm and correct people, and given this fact, when they leave Albania, they quickly earn as much money as they need to provide their family not only with a living, but also a very good economic situation. . For this reason they have good, big houses and with a beautiful architecture, they dress in elegant and colorful clothes, while the other villagers have thick clothes and live in small houses and in poverty. Based on this fact, it is understood that these poor people are not the owners of the arable land, but only the mercenaries who receive 2/3 of the harvest, as in other Eastern countries. And although there is no slavery in the Ottoman Empire, in spite of all this, sometimes the bread is trampled on worse than the slaves of their owners, who manage to dishonor their wives and daughters. Farmers looked to them for their most powerful advisers and defenders against the injustices of envious relatives or bloodthirsty officials. It was a miserable time, in which, for the constant negligence of the central government, the right to force ruled in Albania, not the force of law./Memorie.al