Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the testimonies of the Italian General, Emilio Bertotti, Commander of the Special Troops in Albania during the First World War, or as he is otherwise known as “The Great Lufa”, where among other things he writes that: “After being broken by the Austro-Germans, the Serbs saw the passage through Albania as the only salvation. The Serb soldiers, left without shoes and replaced with pieces of blankets, torn clothes and filled with lice and infected with diseases, continued their retreat. During the march, soldiers surrendered their weapons to a chicken or turkey, and officers sold horses and equipment. The unknown story of the First World War in Albania, seen in the book “Our Expedition to Albania” written by the Italian general who commanded the special troops in our country, which also refers to the memories of his former colleagues, such as the Czechoslovak, Rudolf Prohaska, or German, Helmut Shvanke.

The First World War, which also affected Albania, has been the subject of harassment by many foreign historians and scholars, who have exploited memories published by former military personnel in Albania, as well as rich documentation preserved in archives. of Italy, Austria-Hungary, Prague, Belgrade, and several other European countries which were involved in the vortex of that war, have occasionally published books which have aroused interest from numerous readers. The material published in this article by Memorie.al, is prepared from the memoirs of the Italian General Emilio Bertotti, who was the commander of the Special Troops in Albania and published them in his book “Our Expedition to Albania” where he refers. and some of his colleagues in other armies who fought in Albanian territory at the time, such as former German officer Helmut Shvanke, or the memoirs of former Czechoslovak officer Rudolf Prohaska, in a book he published in Prague in 1928, etc.

Death of 43 thousand Serbs in Albania

Seeing that the Serbian army of Krajl Peter was finally defeated on the battlefield by the Austrians, as the only way to save alive the rest of that army, it was seen crossing the Albanian territory to go to the Adriatic Sea, and then to return to Belgrade. The withdrawal of the Serbian army through Albania is considered one of the most tragic events of the First World War, or as it is otherwise known by many scholars who have dealt with that period as: “The Great War”.

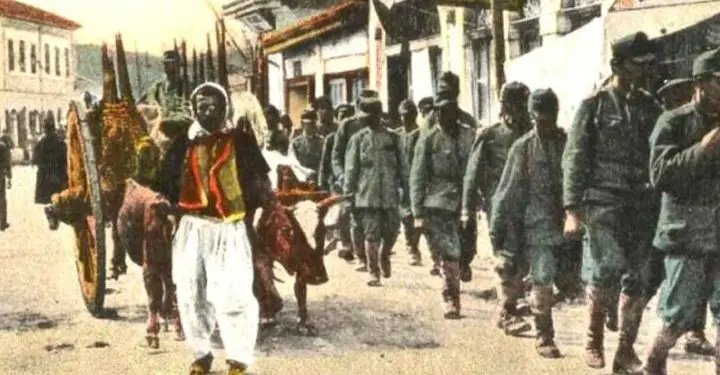

Since the beginning of October 1915, after the Serbian army was attacked in its northern part by Austro-German forces and in the east by the Bulgarians, who aimed to prevent the unification of the Franco-British forces, which were deployed in the Vardar Valley. , the Serbian army was forced to retreat to the west, where it had the support of the Montenegrins. Following this decision from Nis where it had been deployed, the whole army began to withdraw, and at the head of the long column of 70,000 troops, they had put the Austro-Hungarian captives, who had captured them during the fighting in the first phase of the war.

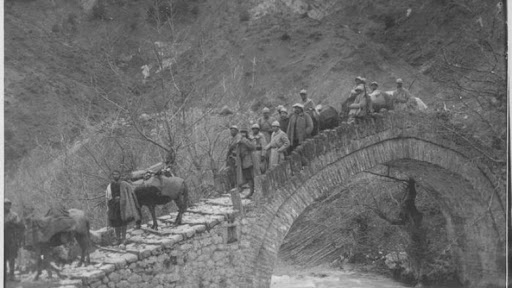

According to various Italian archival sources, the journey of that long column of Serbian forces through the mountains and snow-capped reefs of northern Albania was a real hell for the Serbian army, who were forced to march day and night over and over to escape. from the revenge of their opponents, who were following them from the north and the east of Serbia. During that exhausting march from the harsh weather conditions, in the ranks of the Serbian army, which was also malnourished, there were heavy losses from the typhoid epidemic that affected a large part of the army, causing them to escape that ordeal. only 27 thousand of them. He wrote about this in his memoirs and the former Czechoslovak officer, Rudolf Prohaska, in a book he published in Prague in 1928.

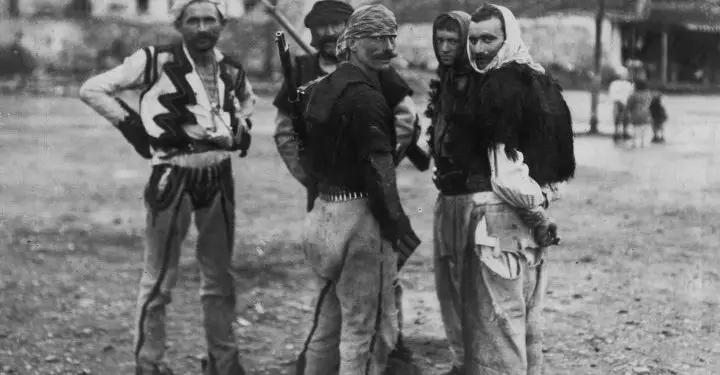

In his memoirs, Prohaska writes: “During those two months, the withdrawal of Czech prisoners along with the mass of Austro-Hungarian prisoners at the head of the Serbian army was a terrible experience for us. At that time we were walking and marching exhausted through that frost and frost, wherefrom moment to moment we could find death from the surprises of that road in the snow-capped mountains. Most of the soldiers were somewhat relieved by the personal equipment they carried on their backs, because along the way near the villages they had exchanged clothes and blankets with genius meat and potatoes, with the rare inhabitants of those areas where we passed.

After detailed descriptions of that march, the former Czechoslovak officer, Prohaska, captured by the Serbian army, talks about Albanians in his book. Among other things, he writes: “Equipped with a relentless instinct for freedom, but deprived of a sense of discipline, in bloody and constant rebellions with his own authorities, unprepared for any spark of state acceptance and divided into clans eternally rivaling each other, they preferred to deal with Austro-Hungarian captives rather than with Serbs who viewed them hostilely.

At the end of that chapter, where Prohaska talks about the suffering and torture suffered by Serbian soldiers during the grueling march on Albanian territory, he says: Anyone who was exhausted died without being able to get any help. During that march, the Serbs threw into the Drin River all the equipment that prevented them from walking, such as trucks, cannons, and even the car of their King, Peter.

Occupation of Albania

Regarding the whirlwind of the First World War, which included the Albanian territory, the German author Helmut Shvanke, among other things, writes: Mesopotamian, Dardanelles, various colonial fronts and the one for the possession of the Suez Canal, the Albanian front was the one that lasted the longest, postponed until the end of the world conflict, although certainly one of the least bloody. But it has been a front with very dramatic aspects, if counted in addition to the Serbian army, the naval war, on the surface and under the sea for the control of the Otranto Canal. The Albanian Front was also strategically important in limiting the annexationist pressures of the border countries and because it had entered the Balkan anthem of the Balkans. Independent a year before the outbreak of World War I, Albania returned to be an occupied country during the conflict, as it had been for centuries by Roman and Byzantine invasions. In that great war, it was occupied in two-thirds of its territory, by the Austro-Hungarians, and in the rest, in the South by the Italians and the French. The bombing of Durrës, which took place on December 6, 1915, by the ships of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, had pushed Esad Pasha, who at that time had Prince Vidin, to retreat to Tirana. Moving from Lake Ohrid, the Bulgarians penetrated through central Albania and occupied the cities of Berat, Fier, and Kavaja. In November of that year, the German supreme command had almost completely withdrawn its troops from the Albanian front. The Austro-Hungarians were free from this and decided to invade Montenegro and Albania. The Germans saw this as an unsolvable and debatable solution for their Austrian allies because it was impossible to supply the army in the roadless regions of those countries where hostilities between the populations were evident. In this context, that action would require a major military disproportion. For the invasion of Montenegro, the Austro-Hungarians actually used more troops than in Serbia, which was equal to 20% of the local population. After occupying Lovcen in early January 1916, the Austro-Hungarians had the freeway to march towards Shkodra and Northern Albania “, writes the German author, Helmut Shanke, in his book.

Austro-Hungarians in Vjosa

According to the Italian general, Emilio Bertotti, who was the commander of the Special Troops in Albania and published them in his book “Our Expedition to Albania”, based on the situation that was precipitating at that time in Albania, the Italian troops benefiting from the difficulties of the Austro-Hungarian troops, they started the defense of Durrës with the “Savona” brigade, the 159 territorial Battalion and some artillery batteries. But despite the commitment of all these forces, in February 1916, Italian troops were defeated by attacks by four Austro-Hungarian brigades. By the end of February, the city of Durres had been completely emptied of Italian troops who boarded ships but were unable to take with them artillery installations, which remained completely intact in the hands of the Austro-Hungarian army. After the fall of Durrës, in April 1916, Austro-Hungarian troops advanced to the banks of the Vjosa River, which marked the frontier line with the Italians.

The objectives of the Italian expedition in Albania remained almost limited to the possession of the southern part and to the east with the Franco-British Army, commanded by the French general Serrail, operating in Thessaloniki. Despite the neutrality of Athens that was broken only on August 29, 1917, when Greece entered the war by joining the Entente, the Eastern Army grew by 220 thousand French, 120 thousand English, 80 thousand Serbs, 20 thousand Italians ( under the command of General Petit) and 16,000 Russians. The connection with the Franco-British made necessary an Italian operation which led to the evacuation and evacuation of the Albanian territories occupied in the South by Greece since 1914 and annexed in March 1916. On June 28, 1916, the Italian units captured the region of Himara and there from the beginning of September and the centers of Tepelena, Gjirokastra, Delvina, and Saranda. Shortly afterward, they came into contact with French vanguard in the Korça region. In the occupied Albanian territories, the Italians and Austro-Hungarians did their best to gain sympathy and military cooperation with the local population, and from this, the Italians managed to put together two battalions of local troops, against various battalions recruited in the north by their opponents.

Italo-Austro-Hungarian conflict

Given the internal conflicts that had engulfed Greece in the rapes of French and British territorial sovereignty, the resignation of King Constantine, who had been replaced by his son Alexander, was provoked in June 1917. At that time, on the 29th of that month, Greece went to war with the Entente and its territory became the basis for military action in the Balkans. After the general mobilization, of the three divisions that were in early 1918, at that time their number reached nine.

That same spring, French attacks on the territory of Lake Ohrid shattered the sluggishness of the Albanian front, forcing the forces of the 19th Austro-Hungarian Corps to disband, whose defense system went into crisis in July of the same year. year as a result of the intervention of the XVI Italian Corps. As a result, after losing the Mallakastra hilly chain northeast of Vlora, the Austro-Hungarians were forced to retreat to the front line for about thirty kilometers. On October 2, 1918, the 16th Italian Corps, consisting of several Infantry Brigades and Artillery Regiments, launched an attack against the Austro-Hungarians, who limited their resistance to the withdrawal.

The Austro-Hungarian troops commanded by General Karl von Pflanzer-Baltin, from the wells they had encountered in the Mirdita region, had left in the hands of the Albanian rebels about 1,200 rifles and 10,000 Austrian gold crowns. Taking advantage of the great losses of the Austro-Hungarian army, Italian troops entered the city of Elbasan on October 8, 1918, and on the 14th of that month, they entered Durrës and a day later in Tirana. After the fall of Tirana, on October 31, Italian troops entered the city of Shkodra, which all came under international administration.

The breakup of the Italians in 1920

The end of the First World War, or as it is otherwise known by foreign scholars as to the Great War, rekindled anarchic hearths in Albania and annexationist hopes in neighboring countries, which all emerged victorious from that war. The repatriation of the marked contingents of the Italian Special Forces and the transfer of some units to Montenegro and southern Dalmatia, in early 1919, seriously weakened the Italian military position in Albania, which could not be improved even with the arrival of six Alpine battalions. which were sent specifically from Italy.

The gangs of thieves who plundered the provinces, after being well-armed with the spoils of war, benefited from this. From the attacks on Italian troops in Albania at the time, which for Italian General Piacentini meant “the beginning of a prelude to a possible revolution on the part of the Albanians”, he forced what happened in May 1920. to return to Italy the military garrisons that were scattered in the main cities of Albania. After the French had fled Shkodra and Korça earlier that year, only the Italian garrison of Vlora remained in Albania, reduced to 1,800 troops who were attacked by 6,000 Albanian forces in June of that year. At first, the Italians were able to withstand the Albanian attacks, but then they were defeated and withdrew from Vlora. The only one left in the hands of the Italians at that time was the island of Sazan./Memorie.al