The Parish of Gomsiqe: The Seat of Gjeçovi’s “Kanun”

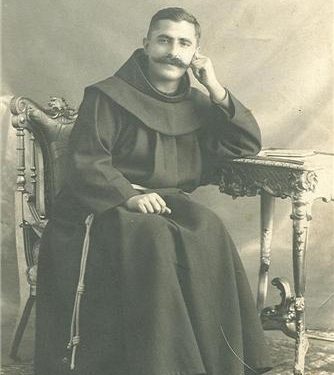

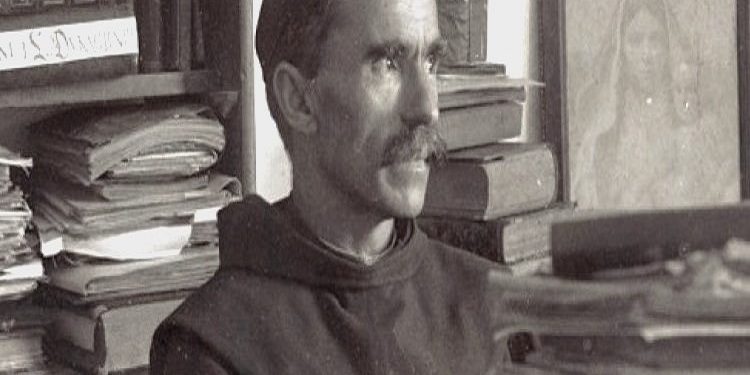

Memorie.al / Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi were the model of the Albanian scholar who lived and worked in the provinces. While many scholars of the time engaged in scientific work in Shkodër and Tiranë, near archives, libraries, and scientific nuclei, Father Shtjefni built his research-scientific center where he went, starting with records, archaeological finds, ethnographic exhibits, etc., which included books in Albanian and foreign languages. The parish among the mountains was both an object of worship for the spiritual formation of the inhabitants and a hearth of scientific knowledge.

In truth, nothing new had happened if we consider the history of monks in the Western world, who prayed, studied, and worked the land. But the news is that this was not done in the abbeys and monasteries of France, England, Spain, Italy, Austria, Poland, Portugal, etc., which had a tradition in this field, but in poor Northern Albania, where customs, songs, tales, and old artifacts of the national cultural treasury were diminishing day by day. If they were not collected and documented by the turn of the 20th century, the coming generations would no longer possess them.

In the Albanian context, the parish, as a culturological metaphor, is much more than the tracing and archiving of the old. The Albanian author, the writer, emerged from a church, from the enlightened parish of Buzuku. The first was the Word… of the Meshari (Missal), “being the first work and very difficult to implement in our tongue!” Since the day this pioneering book first appeared in the window, the Albanian author has signed according to the inalienable style: “I am Don Gjoni, son of Bdek Buzuku…”!

Can other old writers be understood without the parish: Pjetër Bogdani, Pjetër Budi, Frang Bardhi, Gjon Nikollë Kazazi, Pali of Has? Or the Bishop of Arbënia, Mark Skura, of Durrës, Rafaele D’Ambrozio, the prelate of Independence, Dom Nikollë Kaçorri, etc.? From a parish in the Mat mountains, we also have the first document of the Albanian language, the “Formula e Pagëzimit” (Baptismal Formula) of Pal Engjëlli. There is a continuity of writing since antiquity. Saint Jerome (340–420), the Roman author of Illyrian origin, is also the leader of this enlightened race of scholars. It is these wise workers of letters who configured the parishes in the highlanders’ lands as study centers, especially the Benedictine Abbeys, where they worked the fields and vineyards, wrote, transcribed, and archived.

Meanwhile, the folk rhapsodists hastened to pronounce the epics, the songs of the heroes (kreshnikëve), of the seasons, of history, the songs of birth and death, which would be recorded on paper by the culturologist parish priests Bernardin Palaj, Donat Kurti, Aleksandër Sirdani, etc. The parish (Monastery, Abbey, and Bishopric) would not cease to create and sign in Albanian the essence of the Albanian identity.

Gjeçovi re-dimensioned the meaning of the parish as a center for research and study. He had a boxwood staff, a witness to the addresses he visited, from Malësia e Madhe to Labëri, Mirditë, Pejë, Gjakovë, Elbasan, Berat, etc., which started with the carved words: “Rrnoftë Shqypnia” (Long Live Albania). About 30 years with that staff in hand, like an “old man” of knowledge, the first Albanian archaeologist and ethnologist. Gjeçovi’s emblematic staff, to which the poet Xhevahir Spahiu dedicated a poem, is kept in the Shkodër museum, being the extraordinary guide of the heroic scholar’s journeys.

The missionary map of Gjeçovi and his life’s work, “Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit” (The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini), encompasses all the Dukagjini territories and broader Albanian regions: Kryezi, Janjevë, Troshan, Lezhë, Shkodër, Bogë, Pejë, Gomsiqe, Orosh, Kashnjet, Rubik, Laç (Sebaste), Vlorë, Zllakuqan, Zym, etc. Among all these, the parish of Gomsiqe in Mirditë stands first, serving as a connecting bridge with Shkodër, Pukë, and Dukagjin.

It is Faik Konica, the aristocrat of the Albanian-American metropolis, who sketches Gjeçovi’s parish in a few lines, astonished by it as a research studio and museum of archaeological, ethnographic, and other exhibits, calling Gjeçovi “one of the highest men of Albania,” who at the time “was dealing with the old institutions of Albania, of which one that reaches our days is the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini. No one could approach Father Gjeçovi in the knowledge of this Kanun…!”

“On the upper floor of the parish, on a large table, were laid out a collection of Greco-Roman antiquities, discovered and collected one by one, with rare good fortune and a perfect taste, by Father Gjeçovi’s own hand.” This was the Albanian parish of the first half of the 20th century, not only in Gomsiqe but everywhere. The “Bashkimi” (Union) Society of Shkodër, led by Abbot Prend Doçi, was a research academy with branches everywhere in its parishes.

Following the ecclesiastical elite of the Middle Ages, a new line of prelates of the pen and knowledge emerged during the Renaissance, such as: Father Leonardo De Martino in Troshan, Dom Mikel Tarabolluzi in Stubëll e Epërme of Karadak, Pjetër Zarishi in Orosh, Dom Ndoc Nikaj in Shkrel, Dom Ndre Mjeda in Kukël, Father Gjon Karma in Pukë, Archbishop Luigj Bumçi in Kallmet, Father Bernardin Palaj in Dukagjin, Dom Nikollë Kimza in Kalivare, Dom Dodë Koleci in Ndërfanë, Father Pal Dodaj in Rubik, Father Pashk Bardhi in Vig, Dom Prend Suli in Kashnjet, Dom Nikollë Gazulli in Shkrel, Dom Nikollë Mazreku in Kryezi, Dom Zef Oroshi in Ungrej, etc., whose parishes were also creative and study centers.

The national mission of the parish extends to Vlorë, where Dom Mark Vasa stylized the national flag that would be raised in the historic city in 1912. Fishta and Gjeçovi were two of the peaks of the Franciscan elite who created the pinnacles of the culturological corpus, with “The Kanun of Lekë” and “The Highland Lute,” by enabling: the former the transition from the anonymous rhapsodist to the genuine literary author, who does not immediately sever the thread of creative tradition, and the latter – by taking upon himself the “authorship” of the Kanun, which until then belonged to the people. Therefore, they are also the two most popularized friars in the first half of the 20th century, known even abroad.

Gjeçovi made the mountain towers part of his own studio. Two of the distinguished bards from whom he gathered much valuable Kanun material were: Çup Kolë Skana of Orosh and Palucë Prengë Gjoni of Kashnjet, as well as some captain from the Gjomarkaj family. These, along with Ndue Prengë Nikollë Lleshi i Simonit, the Elders of Fan, and others, were Kanun judges, and ‘Plak Kanuni’ (Elder of the Kanun) was a title of nobility, different from the inherited titles of the region’s, flag’s, or village’s leaders. The title ‘Plak Kanuni’ was won through individual abilities in conflict resolution and was not inherited. The ‘Plak Kanuni’ was the embodiment of justice in the eyes of the public. Noted Kanun judges were also sought out in neighboring regions to arbitrate.

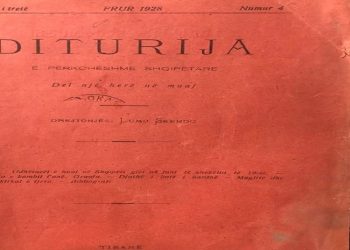

No one knew this supreme race better than Gjeçovi, from whom he “picked” the Kanun day after day and week after week. His parish in Gomsiqe, where he stayed for over ten years, gradually acquired the attributes of a culturological institute. There came a time when the mountain parish priests were simultaneously collaborators of cultural-religious press organs, such as Hylli i Dritës, LEKA, Kumbonma e së Dielles (The Sunday Bell), etc.

In this view, today’s Albanian should definitely make a stop at the Kuvendi i Arbnit (Assembly of Arbër) (1703) in Mërçi (Lezhë), as that temple blessed a historic Albanian assembly of national proportions, to erect an obelisk there. Just as one should discover Prend Doçi, in his two “abbeys,” that of Orosh and the “Bashkimi” (Union) Society (Shkodër), which gave this nation its own alphabet with Latin letters, with which Albanians everywhere write and sign today.

On the road to the Albanian author, we must certainly meet Dom Ndoc Nikaj (in Dajç i Bregut të Bunës, etc.), dealing with the History of Albania (its first history), Shkodra e Rrethueme (Shkodra Besieged), Bukurusha (The Beauty) (the first Albanian novels), or the humble linguist with the lesser-known name, Dom Dodë Koleci, who, established in the parish of Ndërfanë (Mirditë), drafted the ‘Fjaluer i Ri i Shqipes’ (New Dictionary of Albanian) (1908).

The culturological parish was also in “Andrra e jetës” (The Dream of Life) of Ndre Mjeda, the lyrics of his own city by Vinçens Prenushi, the melodramas of Ndre Zadeja, the music of Father Martin Gjoka and Dom Mikel Koliqi, the first Albanian Cardinal. In one of the oldest Albanian parishes, that of Saint Demetrius of Kalivare (1154) in the Land of Spaç, the historian Dom Nikollë Kimza wrote valuable articles, especially for the history of Mirditë, but also of Tiranë, or in the many parishes where Dom Prend Suli served, collecting “old Mirditor kernels,” folklore and customs of the region, as well as many other parish priests who were writers, linguists, ethnologists, painters, museologists, archaeologists, etc.

A great cultural merit belongs to the later parish priests, distinguished scholars, Dom Simon Filipaj in the vicinity of Ulqin, the translator of the Bible into Albanian, and Father Vinçens Malaj, who melted like a candle in his Albanological library in the parish of Tuz, to bring us the Assembly of Arbër through the archival testimonies of the Vatican. In a vanished parish, there may also be “the most important monument of Northern Albania,” – the renowned geographer Armao tells us, referring to the Benedictine monastery of Shirq on the bank of the Buna in Shkodër, built by the Illyrians in the 6th century.

In the Arbërian parishes of Shkodër, Mirditë, Stubëll, Dhërmi, Kurbin, Vele, Pllanë, Blinisht, Orosh, Gjakovë, Prizren, Shkup, Zllakuqan, we have the first Albanian schools; the itinerant missionaries of blood feud reconciliation, Jungu and Passi, in the second half of the 19th century; the distinguished Albanologists Zef Valentini, Fulvio Cordignano, etc.; the first parliamentarians Father Gjergj Fishta, Father Ambroz Marlaskaj, Dom Ndre Mjeda, etc.

We must affirm and testify through studies and publications the cultural role of the Albanian parish, especially at the turn of the 20th century and its first half, without fear of slipping into some kind of cultural “religionism,” because we come from an ideological world unsettled by communist atheism, from a laicism with deformations, and we are moving towards a “vigilant” world regarding the approach and spectrum of beliefs, etc.

In the style of the old priests, especially the Franciscans, other intellectuals far from the metropolis have also spent a lifetime on literature, research, writing, and translation, such as Lasgush Poradeci in Pogradec, Jakov Xoxa in Apolloni, Ndoc Gjetja in Lezhë, Dom Frano Illiaj in Kurbin, Dom Simon Filipaj in Shëngjergj & Kllezë of Ulqin, Dilaver Kurti in Mat, Fatos Mero Rrapaj in Myzeqe, Xhemal Meçi in Pukë, Shtjefën Ivezaj in Tuz, Prend Buzhala in Klinë, Gjon Gjergji in Krushë e Vogël, Agim Faja in Shijak, Gjergj Vlashi in Durrës, etc.

Finally, in Gomsiqe, a Mirditor village on the western edge, it would be appropriate to have a Museum of the Kanun, where the unparalleled research-scientific work of Father Gjeçovi would be immortalized. It is enough to see how the contemporary parish priest and historian, Dom Nikë Ukgjini, has revived the temple of Ndre Mjeda in Kukël of Zadrima. In fact, it is past time for a Gjeçovi museum in Gomsiqe, especially in the era of cultural tourism. / Memorie.al