By Dr. LAURENT BICA

Part Two

Memorie.al/ I must not have been more than 5-6 years old. I am sure of one thing: I had not yet gone to school. My mother, my late mother, was teaching me numbers and the letters of the Albanian alphabet in a notebook she had found somewhere, who knows where. These were the 1950s, difficult years following World War II. She told me that she had completed her primary schooling during the time of King Zog, around 1935, in a village in Opari, Lavdar, which was the center of the commune of the same name, Opar. She herself would walk every day from the village of Karbanjoz, together with her sister. Every day, before the lesson began, all the primary school students, which at that time had five grades, would sing a song that was sung in all schools of the Albanian Kingdom, which also contained these verses: “Dhe flamuri kuq e zi/ Do valojë përsëri/ Në Kosovë e Çamëri” (And the red and black flag/ Will wave again/ In Kosovo and Chameria).

Continued from the previous issue

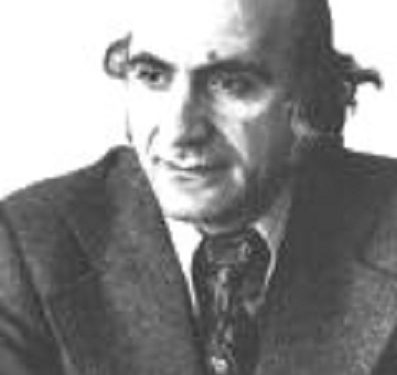

I also attended a lecture by Prof. Dr. Ali Hadri at the Faculty of History and Philology. Among other things, speaking about the Renaissance, the League of Prizren, and the four Albanian vilayets, he deliberately underscored that Ioannina (Janina) is Albanian land, it is an Albanian city. I noticed a dissenting reaction in the auditorium from our history professors at the University of Tirana, and Prof. Hadri was momentarily put in a difficult position.

At a time when Chameria was not even mentioned in Albania, it was heresy, and saying that Ioannina was Albanian was even more severe. I bring up these examples because I remember them as clearly as today, and they are recorded in my mind, down to the smallest detail. They concerned issues that fundamentally interested me, and everything was instantly fixed.

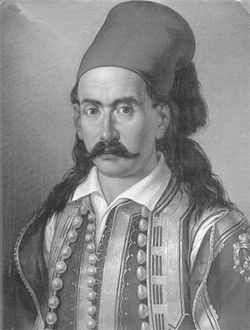

From the 1980s, I will share a detail about Chameria and Hasan Tahsini. There were two distinguished Cham people, one a professor at the University of Tirana, Department of Electronics, Mr. Lutfi Saqe, and the other a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts, Mr. Hilmi Kasëmi; both colleagues, friends, and companions of mine, and both like-minded, with whom I spoke extensively about Chameria and the Chams, about Hoxha Tahsini, Marko Boçari, Abedin Dino, Mihal Artioti, and a host of other enlightened figures from this patriotic region, even back then.

I maintain my friendship with them today without changing a single comma, even though we may have been far apart at different times. Lutfi left for Germany after the 90s, Hilmi went to Italy, and I went to Turkey. Today, the three of us are in Albania, and we maintain our old friendship, coming into contact occasionally to have a coffee when the opportunity arises.

Two days ago, I congratulated my friend, the professor and sculptor Hilmi Kasëmi, for the monument of Father Gjergj Fishta that was placed in the center of Lezha. It is one of the most successful works from his golden sculptor’s hands. His two sons are following in their father’s footsteps. In the 1960s, with these two respected friends, we talked until we were “tired” about Chameria and its Hoxha Tahsinis, and we followed each other’s work and successes.

Time has taken its toll, having sprinkled a little “snow” on our heads, but we remain who we were 30-40 years ago, “fervent Chams,” convinced and dedicated to the national cause. With Hilmi, we have discussed and continue to discuss the immortalization of the most prominent personalities of Chameria in sculpture. In the 1990s, those simple conversations of ours about Chameria would materialize in the anthem of the patriotic association “Çamëria” and the newspaper “Çamëria-vatra amtare” (Chameria-Ancestral Hearth), from which the suppressed Cham voice of the monist period would burst forth.

The three of us, Lutfi Saqja, Hilmi Kasëmi, and I, rushed as fast and as much as we could to join the ranks of the “Çamëria” Association and subsequently the Party for Justice and Integration of Mr. Tahir Muhedini. I do not want to elaborate on this, as it belongs to another time, and I do not want to stray from the framework of the subject I am examining, concerning the Tahsinian research…!

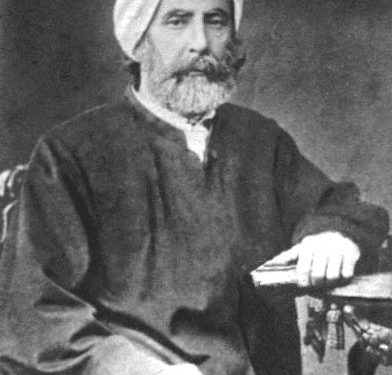

Writings During Hasan Tahsini’s Lifetime

Hasan Tahsini was born in 1811. In the 1820s and 30s of the 19th century, he lived in Albania, in Shkodra, Berat, and his birthplace, the village of Ninat in Filat. Apart from some distant echoes from oral tradition and other sources, we have no specific data about this period. Written sources about Hasan Tahsini are not found in Albania. Neither for him nor for his father. Hasan, at this time, had not yet become Hasan with a capital letter; he had not yet become Tahsin. He only had the simple name Hasan Hoxha from the Ahmetanjet tribe, in the village of Ninat, Konispol.

We also lack written sources for the 1840s and 50s, although he was living in Istanbul then. If one glances at the Ottoman press, it was just taking its first steps, especially in the 50s. The organs in the Ottoman language could barely be counted on the fingers of one hand. No one has entered the Ottoman archives with the genuine goal of researching Hasan Tahsini, let alone for an early period like the one we are discussing.

However, for the 1860s of the 19th century, when Hoxha Tahsini was in Paris, France, as an embassy employee (and an employee of the most important, the main Ottoman embassy of the time), the situation changes somewhat. For the first part of this period, we have an already published diary of the Ottoman Ambassador in Paris in the early 1860s, Hayrullah Efendi, who provides information, among other things, about Hasan Tahsini, whom he also had as a private home tutor for his children, especially for the one who would later become a distinguished Turkish poet and writer, his youngest son Abdylhak Hamit.

In the second half of the 1860s, the number of Ottoman newspapers increased, and Hoxha Tahsini’s name must certainly have appeared in the contemporary newspapers dealing with education issues, such as “Maaref” (Education), “Mymejiz” (The Observer), etc., not to mention the official newspaper “Takvim-i Vekai” (Calendar of Events).

There are three important events in which the name of Hoxha Tahsini surely appears. This is the visit to Paris, London, and several other capitals of Western Europe by the Sultan of the time, Abdülaziz. It was the first time a Sultan had visited the West, and it was given extraordinary publicity. The entire burden of its organization fell on the Ottoman Embassy in Paris. The Second International Exhibition of Industry, Crafts, and Arts were opening (The first was organized in 1851).

In 1867, Sultan Abdülaziz set foot in Marseille and from there to Paris. Among the employees of the Ottoman embassy, Hasan Tahsini was the second most important figure after the ambassador. This was widely reflected in the contemporary press-French, Ottoman, and other countries’. But who has delved into this for Hasan Tahsini? No one!

The French were astonished by the clothes of the Sultan’s guard, who were tall Catholic Albanians from the region of Krajë above Ulqin, and they surprised the Parisians by reminding them of Turks. How did Hasan Tahsini feel when he spoke Albanian with his compatriots, the Sultan’s personal guards, in the middle of Paris?!… Surely at least these were reflected in the official newspaper “Takvim-i Vekai.”

Let’s move on. In February 1869, the Ottoman Foreign Minister, Fuat Pasha, died in a hospital in Nice, France, where he had gone for treatment. The difficult task of accompanying the corpse of the head of the imperial Foreign Ministry was entrusted to the number two of the embassy, Hoxha Tahsini. This included representing the embassy in its escort by a warship to Istanbul, and simultaneously serving as the embassy’s Imam to perform the official and religious ritual of washing the deceased’s body and accompanying it to Istanbul for its final resting place.

Every time I have seen the grave of Mehmet Keçecizade Fuat Pasha in the Sultanahmet area, in the heart of Istanbul, near the Topkapi Palace of the Sultans, in my mind’s eye, I have thought of Hoxha Tahsini. How he directed the magnificent burial ceremony of an Ottoman Foreign Minister and former Prime Minister (several times), one of the main figures who led the bourgeois Tanzimat reforms, alongside a Reshit Pasha and an Ali Pasha.

Imagine what responsibility this man bore on his shoulders during the burial of such a high-ranking functionary in the empire! Was this not reflected in the contemporary press?! Undoubtedly, yes. But nothing has been scrutinized to this day, especially to uncover something about Hasan Tahsini. We come to the events of the university. There are three very important moments related to this epochal event for the Ottoman Empire: the opening of the first pan-Ottoman university.

The duty of presiding as rector, directing it, and organizing it was entrusted to Hoxha Tahsini. The opening of the university was prepared throughout 1869, and the official ceremony took place in February 1870. I do not believe there was a single contemporary newspaper published in Istanbul that did not write about this event and the university’s rector, Hoxha Tahsini.

Superficial research has been conducted concerning the history of the first Ottoman university, especially by Turkish researchers, among whom we would single out Mehmet Ali Aynî with his history of the university published in Istanbul in 1927, or a series of very important modern studies by Prof. Dr. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu.

But the contemporary press still remains unexplored, barren ground concerning Hoxha Tahsini. Various researchers have entered, often foreigners like Americans, Canadians, English, French, Germans, but there is nothing specific about our Tahsini. When he is mentioned, he is treated as incidental; they do not focus on him. Even Turkish researchers, who are more interested in this point, have not, to this day, focused on Hasan Tahsini’s role in the establishment of the university.

Another culminating event, also related to the university, was the scientific conferences held there. In fact, some of them, held by Hoxha Tahsini and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, became the reason for the university’s closure. Thus, both the conferences and the closure of the university in 1871 undoubtedly resonated in the public opinion of Istanbul and beyond.

Similarly, the contemporary press wrote about them and about the two figures that were targeted by the clerical circles of the time and the fanatic environment, as well as by a part of the state bureaucracy, the reactionary circles, refractory to progress in the field of education. They saw the opening of the university as a weakening of their power, of the control that religion had traditionally had over education, a transition of education and culture towards laicism, which weakened their positions.

Therefore, to avert this danger and to frighten others in the future, some “heads were cut.” One of them was that of Hasan Tahsini. He was dismissed from the post of rector and isolated, and was branded with labels like “heretic”, or translated with the language of the East, “gjavur” (infidel), “mësjë Tahsin” (Tahsin the evil/sinner), etc. These had their influence in hindering their path. But men like Tahsini did not give up. They continued preparing cadres for new battles.

Thus, the university’s closure also caused a stir in public opinion, but it was also widely reflected in the contemporary press. How much research has been done is another matter. One fact is that these events concerning the entire empire were reflected in the archival documents that are “sleeping,” as well as in the foreign-language press published in Istanbul, such as in Greek, Armenian, Bulgarian, Arabic, French, etc.

This educational and cultural activity was also reflected in a series of books written at that time about Turkey, in English and French, or even in another language, by authors such as J. Lewis Farley, and a line of other French authors. There is a whole literature in Ottoman and foreign languages that needs to be carefully scrutinized for Hoxha Tahsini.

In 1872, in Namik Kemal’s newspaper “İbret” (The Example), Tahsin Hoxha is mentioned and praised, as a Russian author Zheltjakov expresses, for the establishment of the Geographical Society of Islamic countries and the work it was doing. This notice informs us about the connections this Albanian Rilindas (Renaissance figure), Hasan Tahsini, had with the Ottoman Rilindas, Namik Kemal. They knew each other from Paris and continued their connections later.

Hasan Tahsini, together with his friend Mahmut Nedim, wrote a pedagogical work titled: “Myrebei Etfal” (The Education of Children), in 1873. Its publication certainly resonated. We only have the information from a contemporary newspaper, “Hulasatul Efgar,” where the publication of this work is announced. In our days, Prof. Dr. Jashar Rexhepagiq found this work of Hasan Tahsini, in which he is a co-author, in the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul, where I have been, and he conducts an analysis of it in one of his own works.

Again in 1874, Hasan Tahsini went to Albania. He traveled back and forth across it, engaging in patriotic propaganda and dealing with the dissemination and popularization of scientific knowledge among the masses. He was arrested in April 1874 and imprisoned in the notorious Seven Towers (Yedikule) prison. Thanks to the intervention of Albanian patriotic circles and progressive Ottoman ones, he was released from prison. Surely, this event also left traces, not only in archival documents and European chancelleries but also in the contemporary press. But how much and how it was reflected remains to be left to future research and future scholars of Hasan Tahsini.

Even during his lifetime, the activity of a personality of imperial stature like Hoxha Hasan Tahsin Efendi did not pass without leaving a trace. Our duty and that of future Albanian Ottomanists and Turkologists is to “rummage” through the contemporary press because they will find treasures.

I am convinced that even just one very long-lived Greek-language organ, like “Neologos,” which was published in Istanbul for several decades, will contain information about Hasan Tahsini. For the years 1875-1876, we have no data, but we know that Tahsini was certainly in Istanbul. It must have been the year 1877, when the Russo-Turkish War began and when events rolled one after another, for the name of Hoxha Tahsini to reappear on the scene.

In 1878, Tahsini himself published an article on the importance of the alphabet for Albanians, published in the Istanbul newspaper “Basiret” (Judgment or Wisdom). In that article, he highlights the role of the alphabet as a weapon of knowledge and progress. Also in the same year, in the “Basiret” newspaper, Abdyl Frashëri published an article on the Albanian question, concerning the danger of fragmentation facing the Albanian lands from the Treaty of San Stefano, which was signed in Istanbul that same year.

It is the same newspaper, and its director was Sherafet Efendiu, who was friends with a number of Albanian personalities living on the shores of the Bosphorus, including his colleague, Sami Frashëri. The latter must have been the intermediary for the publication of both Abdyl’s and Hoxha Tahsini’s writings. Possibly, in the case of Hoxha Tahsini, the connection was direct with the director of the “Basiret” newspaper. Whatever the case, what a matter to us is that Hoxha Tahsini is present in the contemporary press. He wrote both before and after. How much we know today is another problem.

In 1879, the “Society of Istanbul” was created, or as it became known: “The Society for the Printing of Albanian Letters.” Hasan Tahsini was also on the alphabet commission. This is fitting, as he was an initiator of meetings for the determination of the Albanian alphabet even during 1869-1872. Indeed, at that time, all the newspapers of Istanbul began to write and refer to Hasan Tahsini as the “initiator of the creation of the society of letters.” This was reflected in the newspaper he published in the Bulgarian language in Istanbul by the Bulgarian Rilindas, Petar Slaveykov.

Hasan Tahsini did not limit himself only to publishing articles here and there during the stormy years of the League of Prizren, but he himself also published, under his direction, the “Mecmua-i Ulum” (Scientific or Knowledge Magazine), which I have seen with my own eyes in Istanbul. Seven issues are known to date, and it was published at the turn of the years 1879-1880. There he also published some works, translations from French Enlightenment figures, or some of his own poetry. His final poems were published in another organ in Istanbul, “Hazine-i evrak” (Treasury of Acts).

In conclusion, we can say that in the 1860s and 70s of the 19th century; the activity of Hoxha Hasan Tahsin Efendi was widely reflected in the contemporary press, in memoir literature, and in the books of foreign travelers who visited Istanbul. Furthermore, this personality himself wrote numerous articles that need to be collected, translated, and published in Albanian, because along with his works in prose and poetry, they are a contribution to the illumination of such an important figure of our nation.

Naturally, until now, the great archival wealth that is “deeply asleep” remains “undisturbed”! It is the duty of the new forces of future Albanian or Turkish Ottomanist scholars to “dig in,” to “immerse” themselves in this multitude of writings that were published during his lifetime, by him or by others, to bring his colossal figure into the light of day…! / Memorie.al