By Prof. Assoc. Dr. Thanas L. Gjika

Part one

(A portrait-biography dedicated to the distinguished activist, Professor Sami Repishti)

Memorie.al / Sami Repishti is one of those who suffered, who, after enduring torture during investigations, the suffering of prison, the danger of escape, and persistent work to qualify and serve the homeland as anti-communists, deserve to be called, even while alive, heroes of the Albanian world. Along with Arshi Pipa and Martin Camaj, he constitutes an elite trio from Shkodër who, with their life and work, furthered the patriotic and intellectual mission of the National Renaissance and of the patriots of the Second World War and beyond. For more than half a century, Professor Repishti has merited the title of an Autonomous Institution through his multifaceted work in defending the rights of Albanians wherever they live, with memoranda, political articles, analyses, essays, literary creations, speeches at conferences, interviews on “Voice of America” (VOA) Radio, his work as a co-founder of several patriotic organizations and associations, and his concrete actions in the homeland and in Kosovo to closely assist the processes of democratization and the creation of a law-governed state.

To draft this portrait, I did not start with the idea that I have untold opinions and evaluations about him, because in this regard, I can help very little. I say very little, because his multifaceted values were highlighted by well-formed intellectuals such as; Agron Alibali, Anton Çefa, Prof. Asc. Dr. Eleni Karamitri, Ph. D. Elez Biberaj, Fotaq Andrea, Frank Gj. Shkreli, Ph.D. Grid Rroji, Dr. Lumira Rroji, Ph.D. Niko Qafoku, Ramadan Gashi, etc., during the Symposium organized on July 18, 2015, on the occasion of his 90th birthday at International House, NY.

Prof. Peter Prifti had previously written: Prof. Dr. Sami Repishti stands at the head of the Albanian-American diaspora intellectuals. He is a worthy successor to the Rilindas (National Renaissance figures) because he faithfully implemented their high ideals. The main impetus for writing this portrait-biography was my desire that such people with special values should be written about continuously, until their values are internalized by many, many Albanians wherever they live, so that we too can achieve an enlightened society like that of the European Union countries, where we aim to arrive…!

Getting to Know Professor Repishti Up Close and the First Meeting

Reading several articles by Professor Repishti in newspapers sparked in me a feeling of deep respect for this analyst who was known for his depth of thought, constructive criticism of the communist regime and the transition governments, as well as for his cultured and dignified language, without insults or affronts to the opponents of his ideas. Such features brought to mind Vaclav Havel (1936 – 2011) and Karl Popper (1902 – 1994). I took courage and asked him to send me his two literary books, “Pika Loti” (Tear Drop) and “Nën hijen e Rozafës” (Under the Shadow of Rozafa).

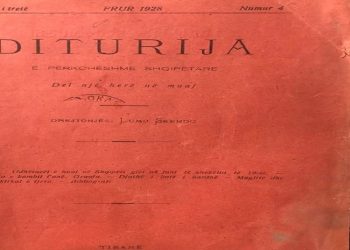

After reading them, I wrote the appreciative article “Communism Kills the Elite, Mistreats the Mediocre, and Elevates the Inferior,” which I published in “Dielli” New York, on March 21, 2013. I had never seen him in person. Learning about his life through reading these works pushed me to meet and personally know this exemplary activist of our nation. In May of that year, I asked him to give me a chance to meet somewhere. He set the meeting in the square in front of the Public Library, at 42nd Street, New York. I couldn’t navigate large New York, so I went a day early to stay as a guest with my cousin, Mondi Thimio, who lived in Ridgewood Queens NY. He took me to the meeting place, where we sat in the chairs at a table and waited for the professor’s arrival. After we met and were introduced, Mondi left.

Professor Sami was driven by his daughter from his home to the nearest train station, and then he had traveled by train and gotten off near the library. From there he had come on foot. He was wearing a dark suit, a white shirt, but no tie. He had an elegant and straight physique, like the highlanders of our Alps. He was taller than me, had no gray hair; his hair, though thinned, was chestnut-colored.

In the photos I had seen of him in the press, I had noticed his oval face, large forehead, and a characteristic sweetness of kind-hearted intellectuals. These features reminded me of the portrait of my Latin professor, the unforgettable Henrik Lacaj (1909 – 1991). While drinking coffee, I felt as if I were meeting with Henrik and Sami, two Shkodrans I admired, one Catholic and the other Muslim, both had cheerful looks and spoke a sweet Shkodran dialect.

They were educated in schools outside Albania. Their culture was evident in their speech, writing, and in the upkeep of their athletic bodies even past their eighties. The conversation revolved around ordinary things without much importance, and then the professor invited me to go for lunch at the TONY’S DI NAPOLI restaurant, where he usually had lunch when he was in New York. The owner was a Dibra native, a friend of his. We walked about 300 meters to get there. The owner was there and greeted us with respect and affection. After a while, he called one of the waiters and signaled him to take a picture of the three of us.

We lined up, placing the professor in the middle. I recalled the experience of Mr. Antony Athanas, who, during receptions at the “Pier 4” Restaurant, Boston MA, would photograph every personality and friend of his, which was, and naturally is, a great asset to our community, but I wonder if his sons preserve this asset. It would be good if most of those photographs were published in several albums accompanied by the names of the people, the dates of the moment captured, and some explanatory notes…!

After sitting down at one of the side tables, the professor said: “Today you are invited by me!” I told him that we were both far from our homes and, since I had extended the invitation to meet, it was up to me to pay. However, he interrupted me, emphasizing that he could not break his rule, according to which, in the first meeting with a friend, he would not allow anyone but himself to pay.

After we ate, the professor read me a new article he had written those days. He hadn’t sent it for publication yet. I was struck by the strength of his thought and the richness of his ideas, his concern for the progress of democracy in Albania. Progressive, humane, and democratic goals and attitudes. The force of expression, the liveliness of his thoughts, and the pleasant language created the idea in me that the author was very young in age, and not close to 90.

I thought to myself: Here is a mind that does not age. It was precisely the youthfulness of Professor Repishti’s thought that researcher Fotaq Andrea pointed out in his paper read at the 90th Anniversary Symposium: The youth of thought in Prof. Repishti is ageless throughout that long journey of life full of effort, struggle, steadfastness, and dedication, when the sufferings of the soul for human dignity in the world of darkness and dictate hardened his high character early on, turning him over time into a weighty Albanian personality, who understood amidst crime, murder, and inhumane torture what Liberty, Human Value, Humanism, and Tolerance mean. In Prof. Repishti, the innocent victim and the winner, the democrat and the patriot, the humanist and the visionary intellectual, full of exemplary wisdom, honesty, and courage, as a worthy son of the Kastrioti Nation, as a worthy son of Shkodra Locë, are embodied in one!

The Second Meeting

In the spring of 2018, the two brothers Sergio and John Bytici asked me to edit their biographical book “SHKOJMË TE BYTYÇËT – Jeta dhe aktiviteti i familjes Bytyçi / Bitici” (LET’S GO TO THE BYTYÇI – The life and activity of the Bytyçi / Bitici family). While reading and especially while editing this book, I became closely acquainted with the activity of the society “Rinia Shqiptare Kosovare në Botën e Lirë” (RShKBL) (Albanian Kosovar Youth in the Free World). This society, during the years 1968 – 1992 and later, until Kosovo was declared an independent state, played a major role in the fight for the recognition of the violations of the rights of Albanians in Yugoslavia, especially in Kosovo, and for the need for Albanian freedom.

The Bitici brothers are making some improvements and additions before publishing this book. I, on my initiative, wrote a portrait about them, to make known both the generous and long-standing financial aid of these brothers and their activity as restaurateurs (restaurant owners) in the service of our national cause and the Albanian-American community in New York. I published this portrait in my new book, “Një letërsi kombëtare, një atdhe i vetëm” (A National Literature, One Homeland). ‘KUMI’- 2018, on pages 337–352. However, the idea that the evaluation of the work of the RShKBL society deserves many other appreciative writings, to sensitize the government of Kosovo and that of Albania to properly evaluate the activity of this society, which became the initiator of the major achievement – the creation of the independent Albanian state of Kosovo. This idea makes me feel obligated to write more about this still little-known and little-appreciated society.

To learn more about the activity of this society, it was necessary for me to listen to Professor Repishti, the most active figure of this society. I contacted him by e-mail and proposed that we organize a meeting here in Worcester MA, with some intellectuals, where he could talk to us about his life and the RShKBL society. He wrote to me that he no longer left the house and that he could host me at his apartment in Ridgefield CT. With my old car, I did not dare to go alone such a long distance, so I contacted Mr. John Lito, head of the Worcester MA “Vatra” Federation branch. He had once told me that he would like to hear from Professor Repishti some memories from the time when he and his father, Milto Lito, were convicts in the labor camps during the 1950s. We agreed that on November 3, 2018, Mr. John Lito and I would go to the Repishti apartment at 1:00 PM. We said we would only stay two or three hours and that to save time, we would have had lunch on the way.

The travel day was sunny and beautiful, so we arrived 20 minutes ahead of schedule. We stopped at a club from where we announced that we were 10 minutes away. Then we went and knocked on the door. The door was opened by Mrs. Diana, the Professor’s wife, an elegant woman with a sweet look and beautiful face, without a single wrinkle. She was the daughter of the Çipi family, Gjirokastra emigrants. She was born in America, but spoke fluent Albanian. Her husband, the Professor, rose from his armchair and approached us, leaning on a cane. He was also tall, unstooped, and elegant, but the bald area of his head had widened, and I thought he had lost quite a bit of weight…!

After greeting each other, the lady of the house showed us a sofa on the left, where the living room was. We noticed the height of the ceiling and the large windows from which the sunlight came. John and I sat on the sofa, while the Professor sat facing us in an armchair. Between us was the center table, where Mrs. Repishti soon placed three small glasses, a bottle of raki, and a crystal dish with some chocolates. She filled the glasses with raki and offered us the chocolates and the raki glasses. After wishing each other well, we men sat down, while the lady of the house withdrew and went into the kitchen area. At first, we asked the professor to tell us something about his family and his escape from Albania.

We learned that the Repishti family had settled in the city of Shkodër from the village of Repisht in Malësia e Madhe, since the 1750s; that they had lived in their own house since 1803; that his grandfather, Jusuf Repishti, had been one of the most active figures of the League of Prizren’s Shkodër branch; that he had signed the June 1878 Memorandum addressed to the Prime Minister of England, Lord Disraeli, to protect the integrity of the Albanian territories at the Congress of Berlin; that his father, Hafëz Ibrahim Repishti, graduated from Istanbul University in 1912, in Islamic theology and law. That he had fought with the Albanian volunteer forces against the Montenegrin army during the siege of Shkodër, from November 1912 to March 1913; that this same intellectual had participated in the political movement of 1921–1924 as a member of the “Ora e Maleve” (Mountain’s Hour) political group of Father Gjergj Fishta, Luigj Gurakuqi, etc., that he was elected as a deputy of Shkodër in 1923–1924 and that in January 1925 he went underground, because as a Fanolist he was sentenced to death by Ahmet Zogu, who had just come to power.

He returned home in November of that year, because he was included in the list of those pardoned by the amnesty announced by President Zogu. Hafëz Ibrahimi died from mistreatment by the Italian fascist police in September 1943, leaving his wife, Havana, the daughter of the Bushati clan, widowed and surrounded by six orphaned children. The eldest son, Sami, had just turned 18, having just interrupted his university studies in contemporary history in Florence.

“Here began my struggle to secure bread for myself and the family,” Sami continued to narrate in his low voice and with an expression of sympathy on his face, and then he resumed: “At the ‘Father Gjergj Fishta’ Lyceum, my classmates included Androkli Kostallari, Vasil Kati, Jorgji Sota, Koli Bozo, Rako Naço, etc., who were connected to the Communist Group of the Albanian Communist Party, while Injac Toni, Luigj Toni, Hamdi Sokoli, etc., were connected to ‘Balli Kombëtar’ (National Front). Eqrem Rusi and I participated in anti-fascist activities without being connected to any party group. After January 1945, as soon as the Directorate of Public Works was formed in Shkodër, I was employed there until October 22, 1946, when I was arrested ‘for activities against the government.’ They called the request I made with some peers for the elections to be free and multi-party an activity against the government. In the cells of the Shkodër Investigation, I was subjected to inhuman torture. I forgot everyone, and from the intense pain, I begged God to take my soul to save me.

After 14 months of torture, I was sent to prison. I spent the years of prison in forced labor camps, in Beden, Maliq, Myzeqe, the airport near Ura Vajgurore, and Rinas airport. In April 1949, my mother, my 14-year-old sister, and my 11-year-old brother were interned in Berat, and later they were taken to the infamous Veliqot camp, Tepelenë. Such very worrying family circumstances caused me great pain and sadness. The day seemed as long as a week, and the week as a month, and the month as a year. This time, as a victim of the communist dictatorship, I suffered much more than I had suffered before as a victim of the fascist dictatorship, and more than I suffered later in Tito’s Yugoslavia.”

John asked him how he managed to leave Yugoslavia for the West, when the agreement for the handover of fugitives was in force between the Albanian and Yugoslav states?! Sami explained that while he was in incommunicado prison in Yugoslavia, he heard that a convict had been returned to Albania, who, when asked why he had fled Albania, had said he had fled because he wanted to go to America. When Sami was interrogated several times, he always insisted and told them that he had fled because he wanted to continue his higher studies in Zagreb. They told him they could send him to continue his studies in Belgrade, but he told them that in Zagreb, the Serbo-Croatian language was taught with the Latin alphabet, and that he found it difficult to learn the Cyrillic alphabet, which was used in Serbia. Thus, after a year, they sent him to Zagreb to continue his studies. Here he attended a language course and later found the opportunity to escape to Italy, where he lived in several refugee camps until he gained the right to go to the USA as a political refugee. / Memorie.al