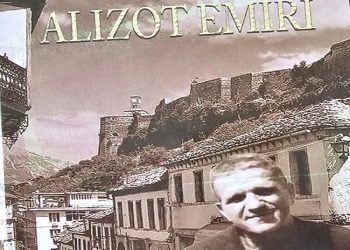

By Vangjush Gambeta

The third part

– The rare testimony of the well-known former journalist of the “Voice of the People” newspaper, who was interned in the villages of the Mat district in 1975, where he worked in agriculture, until the collapse of the communist regime-

Memorie.al / I left the office and headed to the dental clinic, next to the Journalists’ Club. Since I was leaving to go to the meeting, I told my friend to wait for me right there, not at the Journalists’ Club, where we often left the meeting. -No! Not in the Club of Journalists! -Why? – From the first meeting, everyone avoids meeting me in places where there are other people. Nobody likes witnesses. They are right, they hurt themselves and me: “Why did you meet him?”, “What did you say to him?”, “What did he say to you?” The vigilance mechanism starts to work to “detect” the enemies…!

– “The war reaped the brave, while after the liberation the dictatorship put the rabbit in people’s stomachs”!-

Continues from last issue

– Okay, now go out and notify the administration staff. I don’t believe you will leave this job to me. Don’t forget the bakers, the miller, the carpenter, the cook.

The calculator came out. He returned after a quarter of an hour. Immediately after her, the secretary entered the office:

– Did you make the announcement?

– Yes.

The secretary looked worried. When the time was approaching 11.00 people started to gather in the school yard. The activists of the Front had announced that one person from each house would participate in the meeting. It was a warm and beautiful spring day, the sun was shining.

The seniors sat cross-legged on the ground, their backs against the school wall. I sat down too. Mehmet Qerimi, a former Zog officer, an old man with a noble appearance, the first of a large family from Derjana, came and sat down next to me.

Mehmet looked tired. I could tell by his deep but irregular breathing, sometimes more frequent. Age, I thought, approaching eighty…! From the shaking of his hands, from his breathing, I understood that uncle Mehmeti was very worried.

They had brought a table from the school into the courtyard, covered it with a meringue, and placed some chairs in front of the people who were sitting. And the elders of the village came. Among them, an elegant man stood out, who was not our fellow villager. He was the district delegate.

And it was this, the elegant man, this instructor of the Party Committee, who stood up and spoke on behalf of the Front Council. His face expressed almost nothing. Without gestures, with a voice that neither raised nor lowered, calm, as if he was talking about the time that was clear and warm, and not as if he was talking about the fate of an old man, his family and Derjan, that his name would come out as a village, that he had an enemy still undiscovered.

But according to verified information, he said, this old man, Hajriu, did propaganda against the party and the government. In conversations with his fellow villagers, he always complains about his poor life, talks longingly about his past life, complains that the government did not recognize the right to the few properties he had before, and even the debts owed to him were denied fellow villagers for a cow or a goat, which I once sold.

He was not grateful to the government and the Party for the new life it created for him, for the education of the boys and their employment (one a teacher and the other a seller), for the new and happy life of the entire village, with the urban that connects him with Burrell, with an agricultural secondary school, with culture houses and others, and others.

His guilt is very great, concluded the delegate, he deserves to be judged as an enemy, but the Party is generous, and therefore, taking into account his age, proposes that he alone be stripped of the Front card, while all others put their finger to their head and think before they speak again and again, encouraging hostile work.

Thus spoke the delegate and sat down.

The leader of the meeting invited the attendees to discuss.

Silence. No one was asking for the word.

The delegate was worried. And why would he report to the Party Committee, if there were no discussions? He turned his head sometimes to the left and sometimes to the right; he said something to those in his arms in a low voice. Apparently, he was asking them to encourage discussions.

Another two or three minutes passed.

Silence!

The delegate’s face did not express anything. She was cold, ice. Perhaps he himself was not convinced of what he had said. But you have nothing to do! Party duty! A “hit” had to be given in Derjan, as a preventive measure against hostile propaganda.

Silence!

I took out the pack of cigarettes, opened it, took a cigarette, but I couldn’t close it, when I saw Mehmet’s hand, which, twisting, reached towards the box and took a cigarette. He put it on his lips. I was surprised! I knew very well that Mehmet had quit smoking for over ten years. I reached for the match to light it, but he put out his hand, which was now shaking even more, and stopped me. It didn’t turn on. I hesitated, when I saw that Mehmet was shaking not only his hand, but also his face, his whole body.

I was surprised: what was happening? The cigarette on Mehmet’s lips, unlit, was shrinking, entering his mouth, slowly, until it disappeared completely. Mehmet ate the cigarette. In what state of mind should a person be who, ten years after quitting smoking, eats a cigarette, without realizing what he is doing?

At this moment someone from the presidium shouted:

– Mehmet Qerimi! You often talked with Hajriu. Don’t tell us, what did he tell you?

It’s clear: Mehmeti talked to Hajri. But someone told him, or I heard it myself, or eavesdropped on it, then “completed it”, and finally reported it. On this basis, the “strike” was organized.

– We were asked about health. He told me that he has not been feeling well lately.

– No, no, leave these. Tell us why he complained to you, – insisted the vigilante.

– He didn’t tell me anything else! – Mehmeti said sharply and closed his mouth.

Just one phrase, but said in such a tone, as if it were part of a battle report, perhaps left unsaid when he was an officer, part of a battle order that does not allow for discussion. He did not submit to provocation. This one I call “man”, Matjani character.

And the discussions were closed. I don’t know what the district delegate reported, but the truth is that the meeting failed, the goal was not achieved. A couple of very lukewarm discussions, neither meat nor fish, appealed to Hajri to be more careful next time in conversations with his fellow villagers. His two sons also had such discussions, forced to keep their jobs. That the Party was in control of everything, including school, work, and even their lives. That the Party had given Derjani both the high school, the center of culture, and the city to go down to Burrel. That the Party had everything in hand. But the Derjanas in this meeting did not eat the soap for cheese.

Because, at the end of the day, for the wise old man Hajri, it didn’t matter if he had the Front card or not, but only that the boys didn’t get fired. Didn’t kulak Hysen Preni live without the Front card, just like all the other villagers?

The meeting is over. Mehmet Qerimi kept shaking. I asked him:

– How are you, uncle Mehmet?

-I’m fine. Very good. If you tell me I’m not well, they’ll tell me you’re unhappy with the government!

NEW YEAR

The New Year was approaching. I had been living here for six months, in the center of the cooperative, of a cooperative that I could not have imagined. Only once in a meeting of the editors, the editor-in-chief drew the attention of journalists to write more, about the positive example of advanced cooperatives, because there are still in our country, as he said, cooperatives that distribute from thirty lek per working day, as for example in Xibër i Mati, when a pack of “Partizani” cigarettes cost eighteen lek.

After the meeting, I asked the head of the agriculture editorial office, Faik Labinot, how the peasants could live who received thirty ALL per working day. And he answered me: “The editor-in-chief told us how much ALL per working day the cooperative distributes, but he didn’t tell us how much the cooperatives steal…! And who knows how many goats they keep secretly in those caves…?!

I was the only resident of Vanari, which was the center of Xibri’s cooperative. The word “center” was appropriate, because it was really the center of a triangle, at the vertices of which were three villages, Xibër-Hane, Xibër-Murrizi and Keta, which made up the united cooperative of Xibër. In this center were the offices of the cooperative, the warehouse, a small dairy that processed the little milk that the cooperative produced, the post office, the armory, a micro ambulance and a micro canteen.

The sixth month cut off from the world. I was talking to myself for six months. Six months that no one even said “good morning” to me! They greeted me with a slight nod of the head, without saying a word. God forbid, lest some vigilante overhears you and accuses you of making friends with the enemy. In the morning, the storekeeper who was assigned to play the role of brigadier for me, gave me a cup and told me: “Here, go over the offices and clean the thorn”!

But I soon found out why this situation had arisen: word had spread that I was a dangerous enemy. For the first time, during these months, I felt an inner joy: I was also someone, even dangerous, that’s why they isolated me like this. Here’s how I learned this.

One December afternoon, Vanari had fallen into a grave silence, when the great cold had locked the storekeeper in the warehouse, the guard of the armament depot in the warehouse, the postman in his office, the doctor in the ambulance, near the stove. Only the firewood here was out of stock. Wood laths were not known here. The forest was close, go and wait as long as you want, no one asked about the fate of the forest, when they were playing with the fate of people.

I was lying down, wearing a coat, putting my head under the blanket. But from time to time I felt the need to get up, go outside, take a couple of steps to shake off my numb body. I did not fear the cold, which could be about 15-20 degrees Celsius below zero, for the sole reason that it was as cold in my room as it was outside.

I came out. From the window of the office a pipe spewed out black smoke, perhaps it was the chimney of some ship of the time when they worked with coal. The other window panes looked like slabs of ice. I was looking closely at this site with envy: how nice to be in a warm room in this winter, which for me was merciless!

But what am I seeing? Someone is cleaning the ice from a window pane. The glass became transparent and the head agronomist’s face appeared in it, as if on a television screen. He saw me, I saw him. The head agronomist’s face left the “screen” and the door opened instantly. And the chief agronomist told me:

-Come inside quickly, our room is getting cold, come and take a steam.

I entered thinking: What does the chief agronomist have to do with me?! Surprise! What was this invitation? Pity for the enemy of the party and the people? No! It was just humanity, decency. Living among them, I understood more and more that the Matjans have a special respect for the Jabanjis, especially when they fall into misfortune.

He brought me a chair near the stove.

– It is very cold today, – said the chief agronomist.

When the chief agronomist brought the chair closer to me I felt the first warmth, before I felt the heat of the stove. But I didn’t like the beginning of the conversation about time. I knew that people start talking about the weather when they have nothing to say, or when they don’t know where to start the conversation. The first case was excluded. The chief agronomist had no business with me.

The fact that I was not even achieving half the rate was worrying for me, but not for the chief agronomist. I was initially tasked with clearing the brambles, enough to find Kola at work, as the Shkodrans say, enough to give me a few days’ work for a piece of dry bread. The second case remains: the chief agronomist was thinking about where to start.

His meditative face, as if frozen, scared me. If it was for the better, he would have it easier; he would even put his mouth on the gas, just a little. Too bad, I thought. Did something happen to my people in Tirana and they asked the chief agronomist to tell me? That in such cases, always the mind to his own detriment. But I collected myself and fixed my eyes on the chief agronomist, who sat down in a chair on the other side of the stove, as if I wanted to say to him:

“Shoot, then, the desert, what tortures me more”!

The chief agronomist realized that he had to speak. He couldn’t find a better way to start the conversation, so he got straight to the point:

-Yesterday in the Executive Committee, I heard a word that they want to transfer you from here…!

– Where should they send me? – I couldn’t bear to ask him.

– It was about Martanesh, in some isolated corner. I don’t want you to have meetings with people.

– But I don’t even talk to anyone here…!

– I know, I casually threw such a word in a conversation, drinking coffee in the club. But who believes me? Do you know how a strong communist answered me? “You must understand,” he told me, “that the enemy never shows his claws, but puts the water under the rug, with a word, with a conversation”!

But don’t be afraid of us. Men live in these mountains, they never betray the Jabanxhi. But with others, if you had the chance, be careful, don’t talk! And don’t worry. The Martanes are not worse; maybe they are better than us. Memorie.al

The next issue follows