Dashnor Kaloçi

The first part

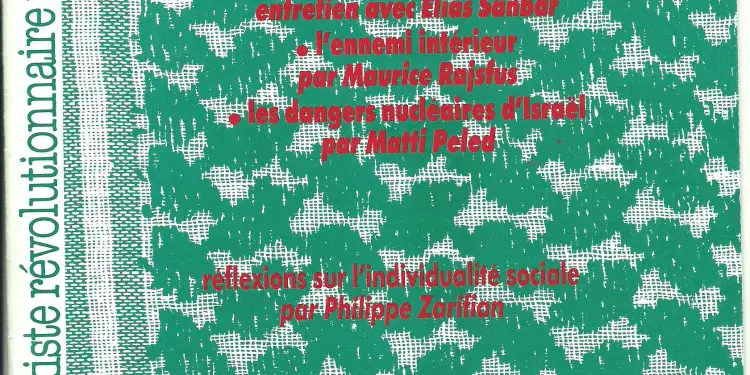

Memorie.al/ brings the unknown memories of Sadik Premte, former chairman of the Communist Youth Group and one of the founders of the SNP, published in the magazine “Le drapeau du socialism” published by the IV Communist International in France, and in two of its 1988 issues, the editorial board published his memoirs entitled “Enver Hoxha a tobacco seller” and subtitle “Memoirs of Sadik Friday, an Albanian communist”. These memoirs were prepared by journalist Maurice Najman, presenting them more or less in the form of an interview…

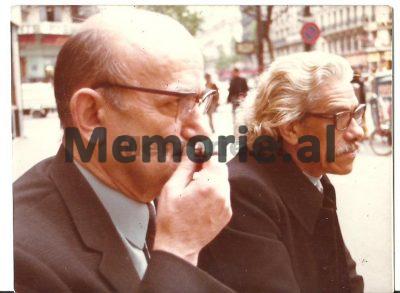

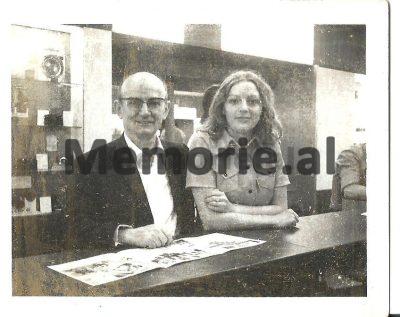

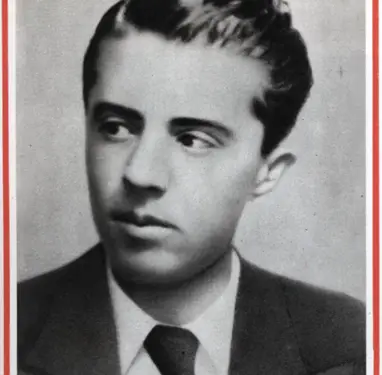

During the entire period that Sadik Premtja stayed in France, from 1946 until his death on April 7, 1991, he had an active life in political engagements as a member of the French Communist Party and also as chairman of the Fourth International. Communist for the Albanian section. As a result, he occasionally published various articles in the magazine “Le drapeau du socialism” published by the IV Communist International, and in two of the issues of this magazine in 1988, its editorial board published Sadik’s memoirs. Friday with the title “Enver Hoxha a tobacco seller” and the subtitle “Memories of Sadik Friday, an Albanian communist”. These memoirs were prepared by journalist Maurice Najman, presenting them more or less in the form of an interview. While the period of their publication a few years after the death of Enver Hoxha and when political changes were beginning in Eastern Europe, most likely has to do with the fact that he did not want to bring further consequences to the family and relatives he had left in Albania. As we will see below in this chapter of the book, Sadiku’s memoirs are with explanations by the editorial board of the magazine and from the beginning they talk about Enver Hoxha, calling him a “tobacco seller”. In this regard, it reads: “The story we are publishing below is an essential evidence against the distortion of the history of the communist movement in Albania. Our friend, Sadik Premtja, tells what happened, in 1941, during the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War, the Albanian Communist Party was formed, one of the founders of which was himself and how, from the beginning, this movement was prey of Stalinist gangrene, which enabled the tobacco seller, Enver Hoxha, to seize power. Below Friday’s memories continue with a chronology of his life and activity, starting from his native village, Gjormi, family and relatives, Fultz American Technical School in Tirana, acquaintance with communist ideas, adherence to The Communist Youth Group, the founding meeting of the Albanian Communist Party, the contradictions with Enver Hoxha and the fight he waged to eliminate him physically during the War period in 1943-’44, concluding them with the assassinations of Sadik by of Albanian Intelligence in cooperation with the Albanian Embassy in Paris, etc. etc. Things that we will see expanded as published by the French magazine organ of the Fourth Communist International giving them in full and without any cuts.

Enver Hoxha, a tobacco seller

Memories of Sadik Friday

An Albanian communist

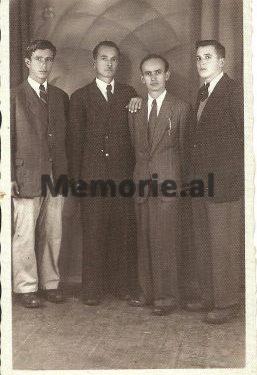

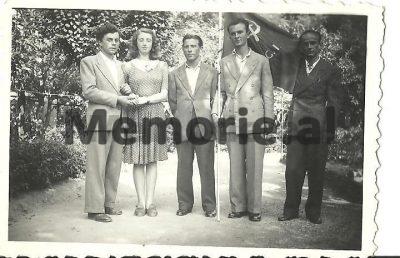

The story we are publishing below is an essential evidence against the distortion of the history of the communist movement in Albania. Our friend, Sadik Premtja, tells what happened, in 1941, during the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War, the Albanian Communist Party was created, one of the founders of which was himself and how, from the beginning, this movement was prey of Stalinist gangrene, which enabled the tobacco seller, Enver Hoxha, to seize power … Gjormi was a typical village in pre-war Albania. With a few wooden huts around the mosque and a pharmacy, the hard life of the village was maintained by a mountainous farm. The tax collector was the only visible presence of the state, if we can call it that ostensibly administration, that the feudal lords had set up in the villages, before in the early 1920s, a so-called central government achieved national unification, under the tutelage of a Republic as short-lived as well as clumsy. This is where I was born, in January 1915. Like all the inhabitants of Gjormi and like 80% of the inhabitants of Albania, my parents, my family, were poor peasants, owners of a small piece of land, of some sheep and goats. . Like everyone else, we were Muslims, but we did not follow the rules of the religion even during the month of Ramadan, when only my grandmother fasted. Even the young people made fun of “those old men” who went to the mosque. I spent all my youth in this village, isolated from everything, without any data about the world, without radio, without newspapers. Political life? We did not even know the meaning of this word. Albania at that time did not know at all what political parties were. Elections were held at the time of the Republic, when deputies were to be elected to Parliament. It was actually an indirect system. An “electoral college” was elected in the villages. Its members then elected members of Parliament. A cousin of mine was chosen to represent our village. But why they chose him, I do not remember. As far as I remember, politics, political programs, human rights, and the like, did not even get in the way. He had agreed with a candidate for deputy that he would give his vote, if he promised to provide a scholarship to the Technical Institute of Tirana, to his new cousin. So after four years of studying in Vlora, I was able to leave for the capital. At the time, Ahmet Zogu, the country’s future king, was a landowner whose family lived in the highlands, as well as the interior minister of the Republican government, whose president was the country’s Orthodox patriarch, Fan Noli. Fan Noli was known as the writer and translator of the Rubairas of the Persian poet Omar Khayyam, whose characteristic feature was the questioning of the existence of God. In 1923 Zogu organized an uprising against the Republic. Fan Noli responded by calling on the people to stand up. At that time everyone was armed; there was no regular army, only a few militias in the service of the feudal lords. The civil war escalated rapidly, forcing Zog to take refuge in Yugoslavia, where he was kindly received by monarchists and White Army groups, with whom he also associated. Fan Noli, like many young Albanian intellectuals, did not hide his sympathy for the October Revolution. In 1924 he demanded that the Albanian Parliament observe a minute of silence over Lenin’s death. This disturbed the surrounding countries, especially Yugoslavia, which, from that moment on, did not spare its support for the monarchist conspiracy against the Republic of Albania. In this way Zogu, with the help of the White Russians, was able to set up a regular army, with which he invaded Albania. The new civil war lasted about three months. But what can the unarmed peasants do against Zog’s well-organized army? The defenders of the Republic were quickly crushed. The villagers did not understand why Fan Noli had to associate with the Republican feudal lords, which prevented him from giving the civil war a social content. After the defeat, the Republicans emigrated to Italy and France, while Zogu was appointed president of the Republic, before being proclaimed by the Parliament, king of the country, under the name Zogu I, king of the Albanians. From this moment something was created that resembled a “modern” state, with the army, the police, and so on, but without any major change in the lives of one million Albanians, who always remained far from the great currents of thought, without political life, without unions. Most of the Albanians are poor villagers, 80% illiterate. My conscious life started when I came to Tirana. Back then the capital was a very small town, a small town, so to speak, with some 30,000 inhabitants, kept alive by the bazaars, where the villagers of the surrounding areas, twice a week, were allowed to sell their goods. By 1934 I was making it a hassle-free life for a scholarship student. But that year things changed. Royal police uncovered a Republican plot and arrested some twenty intellectuals and merchants who, after some suspicious contact, thought they could take over the army. Unorganized and without a clear program, they were quickly discovered, or denounced. Two of my cousins were involved in this futureless plot. One of them managed to escape to Greece. The other was arrested and sentenced to death. My revolt against the monarchy begins immediately after this event. At the institute all the students talked about the “issue”, although, in general, they had no idea what the essence of the issue was. Beware of the King’s countless spies, who were circulating everywhere, I began trying to contact young people who, like me, wanted to “do something.” So one day I came across some students who gave me a brochure written by Kropotkina. It seemed like a revelation to me. I discovered the world with great joy, which surprises me even today when I think about it. Reading this booklet made me really decide to go to war. But then this to me as if it did not mean much, that I did not know what to do. It was at this time that I met Anastas Lulon. He was also a student of the Institute. We had ever met. But I did not know he was a communist. He had discovered me. He knew my anti-monarchist feelings. In that period, a Republican quickly became a communist. Anastasios was part of a faction of one of the country’s three communist groups. Albania, then, was the only country in Europe that did not have a communist party, even in illegality. There were some small groups set up on a sentimental rather than a theoretical basis. Each of them held itself as the only “true party”, although geographically their base was simply limited to one city or province. The “Albanian Communist Group”, to which Anastas Lulo belonged, was formed in Moscow in 1928 and was recognized by the Communist International. It was called the Korca group, after the city where it was located. Enver Hoxha, then a tobacco seller, was one of its leaders. Anastasius explained to me Marxism, the ways of exploiting society, the class struggle, the characteristics of feudalism … He told me a lot about the Soviet Union, about the October Revolution … We started recruiting some students, high school students, even girls from the Institute of Women of Tirana. Soon we were added and divided into cells, first with three and then with five. Our activity focused on the problems of formation and political education. We published books, translating into Albanian the major works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and even Trotsky. From the latter we have also published some articles of a military nature, without knowing in fact that they had been banned. Until 1939 we had no ties to other communist groups, nor any real political activity. The occupation of Albania by fascist Italy on April 7, 1939 changed the situation. On the eve of the occupation, the inhabitants of Tirana gathered by themselves in front of the King’s Palace, demanding weapons to fight the fascist troops. A minister came out on the balcony “to speak on behalf of the king.” He said that “the king was ready to go to the mountains on his own to fight fascism”, but “the people had to be patient”. As some army forces and several hundred civilians struggled to cope with the advance of Mussolini’s armies, the King packed his bags and fled to Greece, Great Britain, France, Egypt, and beyond. The invasion immediately created a fertile ground for us to recruit new members. Our only problem then was to organize as many people as possible, to form cadres, to expand the spread of the group, in preparation for an armed resistance. Our most trained militants were sent to various areas to make propaganda against the invaders and to create nuclei of resistance. I remember that during these months, I passed all the villages of Vlora district on foot. When I arrived at a village, I first asked to meet the village elder, to whom I explained the situation, and asked him to call the villagers to a meeting. When the people gathered, I spoke condemning the fascist occupation and calling for national resistance. At the end of the meeting, we elected a national liberation council, which, among other things, was tasked with recruiting the most militant and willing young men to take up arms. But all this activity was aggravated by the division of communist groups. We had some contact with each other and, from time to time, we published tracts and proclamations together. After the Soviet Union entered the war in June 1941, our efforts to bring the Youth Group, with Shkodra and Korça closer together, to establish a unified communist party were in vain. Then, through some of our friends who lived in Kosovo, the Albanian province of Yugoslavia, we sought the arbitration of the Yugoslav communists. At that time I met Enver Hoxha. At that time he was about 35 years old and knew very little. He was a third or fourth category leader. It was very bloated. He left as an intellectual, it is true that he had studied at the University of Montpellier, in France (some say about law, some about literature), after graduating from the French high school in Korça. His father was a wealthy merchant from Gjirokastra. According to the legend, he jumped into the war at a very young age and after completing his studies in France, he returned to Tirana “to take the lead in the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War” …. In fact, he could not take the exams in France and was employed at the King Zog Legation in Brussels. I do not know if he carried out any political activity in France, as they say, but if he was in fact expelled from the Legation for “political reasons”, how he was able to find work as a professor, in his old high school, at the time of King Zog? Indeed, Enver Hoxha, a handsome young man, chased after women and whispers have been circulating for some time that his girlfriends were a non-trivial factor in his university and professional failures. However, in the early 1940s, when I met him, Enver Hoxha had no political authority over the communists. According to his biographers, he led the great anti-fascist manifestation in Tirana, in 1942. Lie./Memorie.al

Summary by Maurice Najman

Continues tomorrow