By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-one

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the ignorant investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Internal Affairs Branch in Shkodër, split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth, and the thumb of my left hand, on October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the wretch Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After cutting my sentence in half because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Rrëps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the political prisoners’ revolt, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a process that is perfectly normal in the democracy we claim to have. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Rilindas” (Renaissance) Government sent Order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for; The dismissal of a police employee. So, Divine Providence was intertwined with the neo-communist “Rilindas” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more and no less, by the former operative of the Burrel Prison Security. What could be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

RREPSI

(Forced labor camp)

Memoir

The First Meeting

(The boat sunk in the swamp)

Maqo Çomo: – “Right, it didn’t take any special skill to be a minister; it was enough to execute the orders of the high-ups and to demand accountability for their execution down at the base. In cabinet meetings, more was discussed about politics than about the realization or non-realization of plans; the directives came from above, the two-year and five-year plans were sent out detailed. I don’t know exactly who dealt with the planning, however, if they weren’t sent ready from the Soviet Union, they were drafted by their specialists who were attached to our ministries.

Thus, the minister remained an honorary role, but this phenomenon was barely noticeable among the people. I tried to be a proper minister of agriculture; I tried to give the best I could. I never abused my position, and I made countless friends among the simple people; no one was afraid to knock on my office door. As long as I was in office, there were no sharp problems, and as a result, I was positively evaluated. But this was one side of the coin, the one that was visible; the other side depended entirely on the affairs being played out in the backstage of big politics.

After the cult of the individual was condemned in the Soviet Union and the concentric circles of this fight were rapidly spreading throughout Eastern Europe, our leaders were at risk of the ground slipping from under their feet, so they hastened to avoid an overthrow. Naturally, as always in crucial moments, a cause and some deviators had to be found to throw the blame for the successive failures in foreign policy, domestic policy, economy, etc., on their backs, and in this case, it was the turn of Koço Tashko and my wife.

They incited an imaginary storm with insults and fabrications, alleging that some espionage networks had been discovered at the head of the leadership, and that was enough for the Security to begin a wave of widespread arrests. To complete the group, deviators and criminal elements allegedly implicated against the enemy powers’ counterintelligence were invented. I believe you know these, there’s no need to spin it out any longer; the case of Teme Sejko speaks for itself. Naturally, the blow to my wife was undoubtedly a blow to me, as her husband, and also to the family and friend circle.

So, one fine day I was summoned to the Politburo, almost the same people who had sealed the marriage bond a decade ago. They presented me with the alternative: ‘Either break up the family or condemn your wife, to keep your current position and privileges, or be with your spouse and share the headlong fall, along with her!’ Of course, I found myself facing a dilemma upon whose solution depended my fate and that of my children, my relatives, and all those who, in some way, had inextricably linked their future to mine. As I told you, I had long understood the dishonest game being played behind the backs of the puppet figures of power.

The previous events, the exemplary punishments of my former comrades from the War and work, from Koçi Xoxe and Pandi Kristo to Tuk Jakova, Bedri Spahiu, and company, had equipped me with the necessary experience. No matter how mercilessly you condemned your relative, you couldn’t escape the subsequent shockwave of the war; you might delay it a little, but not escape it. With full consciousness, I made my choice, perhaps not the best, but the most righteous. I stood by my life partner and the mother of my children.

I told them more or less this: ‘Honored comrades, when I married Liri, you almost forced me to, but now that you ask me to break up the family, it is up to my will. You accuse my wife of betraying the Party, maybe it even happened, but she has never betrayed me as a husband and my children as a mother; she has been a loyal wife and a devoted mother!’

In this way, I predetermined my fate. Ultimately, I was discharged from duty, allegedly for incompetence, and circulated as a farm director. Worried, I awaited further developments, that is, the inevitable end, prison.”

Ilia: – “But later, did you regret the path you chose?”

Maqo: “The way we accepted the arrest, without counteracting, shows that we have been reduced to unconscious, experimental guinea pigs. To a kind of brainless species, simply some dreamers who hope the butcher will let us vegetate for a while longer, even though the end that awaits us is the same for everyone. It can’t go on like this; the people must be made aware of the dead end we have sunk into, and the paths to salvation must be projected!”

Ilia: – “Of course, you are right, but the path to salvation cannot be individual.”

Maqo: “We were lulled by the dreams of youth, supposedly with the triumph of communism we would be saved from the extreme poverty into which we had been plunged by the exploitation of beys and aghas, and other such tales. But now? So many years have passed, and the poverty has multiplied several times, terror has included even the most indifferent. You turn your head back, you see the bloody path and thousands of victims without motivation. The nation’s brain was eliminated; rascals are selling us ideas from the tribunals, inappropriately!

Each of us must ask ourselves: Was this what we dreamed of on frosty nights, under snow and rain? For what did we sacrifice even our lives? The answer comes naturally: No! No! If once in the village there was a bey or an agha, the farmer still felt like the master of his property. While today, several hundred red beys and aghas have sprung up like mushrooms after the rain, and everyone feels stripped of their property, risking their lives. This is the deduction I have drawn from the practice of these years. I have reflected on the illusions of youth. Now that reality is whipping our faces, I have no intention of playing the ostrich.

Undoubtedly, to get out of this bloody circle into which we have been plunged, even with our help, extraordinary efforts are needed. This is not easy to achieve. Communist madness, like amok, has infected an entire people, has drugged the minds and hearts of the youth; it will take years to detoxify from this toxic substance, perhaps after our death. I definitely regret the path I followed, but what value does it have! We are condemned to break through the boiling steam of HELL; we are paying for our irresponsibility! But what fault does the new generation have?”

It seemed this man was deeply disappointed in his utopian beliefs, he sought to relieve his soul of the burden of guilt, but perhaps he had woken up a little late from his lethargy. He was one of the few former officials who had sobered up from the red intoxication.

Reorganization

(Or taking it off Lenka and putting it on Prenka!)

Life in prisons and forced labor camps rolled on like a daily nightmare. Tortures; public lynchings; with stakes; with rubber hoses filled with sand, or cut into meters; ties to electric poles with barbed wire. Then the isolation cells and sentences of thirty days, and as soon as the month ended, after the first day of release, re-sentencing for another month, and then another, and another, so often the punished person “forgot” himself in the cells, for months and years. The case of Tomorr Allajbeu – nearly four years of uninterrupted isolation, or Pal Zefi, which became the cause of the fellow sufferers’ anger and the explosion of the Spaç Revolt, on 05.21.1973. Thus, they imprisoned the prison itself…!

They attached other forms of torture to the arsenal of physical violence, such as psycho-mechanical and psycho-chemical ones. The first block included controls everywhere: frequent physical checks, check at the entrance-exit gate, check at the work front, check in the barracks, check in the bathroom, check in the private kitchen, check at the barber’s, check in the line for roll call, check at the dentist’s, check…, check…, check…, even check during sleep!

It was enough for a policeman to think that something impermissible, according to his own definition, had been introduced into the camp, or that there was a signal that it might be introduced, and the control would begin! Or a spy, to justify the double-ration of bread and the super-ladle of soup, would report that he had supposedly sniffed out that someone was preparing means for escape; again, control. Or, simply for sport, if an officer felt like having a little fun to push through the twenty-four hours of duty: again, control!

The most pleasant way, the one that gave them the maximum aesthetic pleasure, was the moment they saw the enemies of the people’s power exhausted and tormented to the point of complete exhaustion. No one worried about the material damages, the psychological consequences, the disorder, and the confusion left behind by the control. The block of psycho-chemical tortures included: forced cold-water showers in the dead of winter; crucifixion outside in the middle of the square, barefoot, naked, under snowstorms, under pouring rain, in the peak of the summer sun or the icy frost in winter; forced swallowing of dead insects or animals, such as flies, caterpillars, worms, mice, human and animal excrement, etc.

The case of the old man from Kukës, Arif Muja, who was forced to put a dead mouse in his mouth in the cell, bitterly outraged the political prisoners, who were on the verge of a new revolt. The periodic disinfections of the barracks, when they thought that parasites had found shelter in them, was torture upon torture, which they practiced inappropriately, for the most banal reasons. For example, when one of the internal service police scratched his head or simply suspected that a flea he found in his clothes might have attached itself during his duty hours, even though he might have picked up the parasite in his goat shed or at home, in the dog’s kennel; several dozen sanitarians with masks and a pile of bags of disinfectant would land in the camp square.

Then they would dust all the beds and the entire territory, an action that caused a general hullabaloo and was followed for a week straight by delirium, sneezing, straining, vomiting, dizziness, headaches, etc. But the most depersonalizing, insulting, even mentally violating cases were the violent body searches. We were often ordered to strip naked, as our mother had made us. Some condemned snitch, accompanied by police, would examine us closely, from head to toe, to see if we had caught parasites.

There was no more terrible mockery, when you saw the hounds throw the lice they hid in bags in the faces of old men with a load of mustaches. Then they forced them to parade naked for review in front of the council. They lynched them, took their honor, and disgraced them in front of the whole camp. Then they separated them from the others and, still naked, disinfected them with D.D.T.

The honorable men, hurt in their pride by this cruel treatment, could not swallow the insult and either collapsed, poisoned by the physical-moral venom, or suffered psychological shock. At this point of the “spectacle,” the police and spies would burst out laughing, while the rest of us, confined in a ready-to-move position, were forced to follow this painful, contemptuous, and humiliating tableau. Thus salted from head to toe, with the heavy-smelling gray dust, the wretched naked men resembled some ghosts emerging from the grinding mill.

They were left for hours; in summer, in the sun; in winter, in some corner, at the mercy of the wind and rain, until the parasites “died.” Embittered by spite, ashamed by nudity, dazed by the suffocating effects of phosphorus fumes, a moment came when the sensations were disturbed and acted weakly on the psyche. Humiliation negatively affected the worsening of the mental health of the unfortunates, who often ended up in madness. Faced with the scenes of rape, almost all of us suffered the same shock. However, this objective completed the final goal of the executioners; that by increasing the torments, they increased the suffering of the “enemies of the Party” to break them down psychologically.

After all, this therapy made them happy!

In the camp-prisons, the barracks were usually built with wood, clad on the sides with pupulit boards and for a roof; they threw some asbestos eternit slabs. The defective materials, besides being cold or hot depending on the season, had become the most ideal shelter for parasites of all kinds, while the asbestos roofs were the most dangerous carcinogenic radiator of all forms.

Living in massive groups, often eighty to one hundred people in one building, where each person was entitled to no more than seventy centimeters in width and one hundred and ninety centimeters in length, or, converted to a unit of surface area, one hundred and thirty-three square centimeters of space, but these dimensions could also be narrowed, with the increase in the number of prisoners, made diseases spread at the speed of light.

Then add to the above the numerous sanitary deficiencies, such as, for example, six faucet spouts, of which only four emitted water, the unhygienic tanks with oxidizable tin, the carcinogenic bowls made of meat can lids that we used to wash ourselves, plus the foul-smelling pit toilets where three hundred men dumped their excrement, it is easy to imagine what miserable hygiene existed there. Filth and sloppiness dominated the territory far and wide.

This state of collapse had caused many prisoners to lose interest in cleanliness. However, these were the minority, because the overwhelming majority had become aware of the place where they were confined, of the absolute negligence of the authorities, so they gathered their senses and took care to maintain personal hygiene even in those wretched conditions. Furthermore, to keep the internal developments in the prisons under strict and permanent control, they also applied other supplementary methods. One of these forms of camouflaged torture was reorganization.

But what did reorganization represent and why do I classify it as a method of torture? To give a clear answer to this question, I will have to go back a bit, to the history of the first years, and onward. Initially, the prisons were not truly prisons. But some improvised structures adapted for this purpose; such as military barracks, livestock stables, state offices abandoned and degraded, seized cult objects to torture the religious, etc., whose destination had been changed to cram as many people as possible into them.

Inside them, every necessary furnishing for minimal living was missing. There was no kitchen to cook, no beds, no mattresses, no blankets; faucets and bathrooms were missing, where an undefined number of detainees and convicts had to fulfill vital needs. The isolated, besides having to take shelter in narrow corners where they lay down and got up on the side they were lying on, in the absence of toilets, were forced to perform their personal needs in collective pots or tins, and endure the heavy odors of their excrement for days.

Since that time, the expression has remained: “May I see you shit, in a pot or a tin!” as a curse for someone you wanted to see in prison. But if all that was needed for a normal life was missing in those environments, handcuffs, chains, collars, ropes, axes, shackles, helmets, whips, sand-filled hoses, cut into strips, belts with heavy buckles, rubber and wooden sticks, stakes, cudgels, iron rods, and willow rods, etc., were never missing, that is, a whole arsenal of torture tools.

Hundreds of detainees were taken out as corpses from those structures; dead from the stake, from hunger, from thirst, from the heat, from the icy cold of the cells; add to these those who were immersed and drowned in the filthy sewers of the latrines; then many, many others who, finding themselves under the pressure of brutal violence, could not withstand the pressure and chose self-sacrifice, hanging themselves with their tongues out in the window cages or throwing themselves from the heights of the stairs or from the balconies of the investigation buildings.

These victims, already erased from the ledgers of the Internal Branches or deliberately hidden by the prison staff themselves at that time, are nowhere to be found. In the annual balances, these unfortunates were reported as killed in escape attempts, or simply: died of natural causes. But the oral accounts of that small minority who survived the tortures, sometimes even the voluntary or involuntary confessions of the prison police service employees who, either out of mercy or more often out of boastfulness has confessed to these macabre acts, which have reached our ears mouth by mouth.

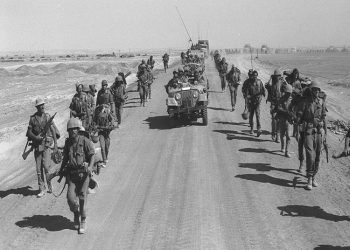

The first arrests of political opponents began before the occupiers had even left because during the War, in the absence of control over the territory, they only applied capital punishment; whoever was caught was killed, even though the crime for which the next victim was accused did not constitute a criminal offense. Later, in the liberated (read occupied) areas, where the communists established power, the prisons or the facilities adapted as such operated above normal capacity. Within a space, let’s say for five people, twenty were confined. In these environments, there were no living conditions; in the absence of toilets, for good or bad, one had to do it in a tin container. The lack of air was suffocating; infectious diseases wreaked havoc. People died for the most banal reasons.

Whoever was lucky enough to escape the scythe of death, still did not come out unscathed; they ended up either in a lunatic asylum or in a hospital, of course, when they were taken there. Mass eliminations were in the interest of the communists because this way, they gained twice; their enemies were thinned out without the trouble of trials, and the expenses for guards and execution platoons were reduced. The extermination methods had their effects from the very beginning; dozens of unfortunates were extinguished within a short period, others were permanently maimed physically or mentally and, as such, became harmless and were neutralized.

Meanwhile, these forms served as a school for future Security agents, where they were trained in practice in the technology of violence they learned in theory, but also as a sieve that separated the “hare-hearts” from those who would later become the regime’s “black hand.” I will talk about how the first political prisoners were treated when their turn comes. Since there was a prison in every district center, often more than one; in the early years, all detainees were concentrated there. The prisons were packed full, but the state guaranteed nothing.

It was up to the families to think about the survival of their relatives; to provide them with everything from food, clothing, mattresses, and blankets. Naturally, the heavy burden that fell on their backs put them to the test of sublime sacrifice. Although facing difficulties themselves, they deprived their children so that they could keep their loved ones in prison alive. They prepared the food, filled bundles with washed clothes, and took them to the prison gates. When they were allowed, even twice a day.

For this, they took advantage of the proximity of the prison to their homes, or to the homes of friends living in the city, when they themselves lived far away. This form of organization was an ancient heritage, dating back to the time of the Ottoman Empire’s jails, which to some extent favored the detainees, because they would always have something to eat, something to wear; when one didn’t have it, others would have it, and everyone was getting by. Thus, when they were released, if they were lucky enough to survive the tortures and were not targeted for disappearance, their health was not reduced to the level the abusers would have wished.

Naturally, our barefoot communists did not feel good when they saw the detainees eating and drinking even where they were. They sought the help of their brethren in arms, the Yugoslav UDBA agents, who, equipped with devilish experience to eliminate as many “Shiptars” as possible, offered them classical and modern torture methods. It was the UDBA agents who conceived the exhausting method, the transfers outside the territories of residence. For example, sending Shkodrans to Durrës, Durrës residents to Korçë, Korçë residents to Vlorë, Vlorë residents to Shkodër, Berat residents to Gjirokastër, Gjirokastër residents to Tiranë, Tiranë residents to Kukës, and so on, increased the quality of suffering and consequently the number of deaths. Memorie.al