By Petraq Xhaçka

Part thirty one

Memorie.al/ The purpose of this book is to join the efforts made to present the truths and horrors of the communist dictatorship in Albania. The main purpose of the book is not to show our people or anyone else, that we oilmen have been innocent, because this has become known from publications in our press, from foreign televisions, as well as from direct meetings with the International Forum and the Albanian Human Rights. The author’s desire, is that through this story, together with other stories, fight any manifestation in any form, even moderate, that he may have to create a communist society. I think that even through this bitter personal history, the cruel, treacherous and overbearing face of Enverism will appear, that for half a century, held the knife with the tip in the chest of the Albanian people, with a pine eye, intercepting the movements for salvation from the outside, or rebellion of the people themselves, ready to push the knife to the heart, at the first movement. The events are set in the economic fields where it has appeared most strongly, such as the oil and gas industry, where I was fortunate to pour my energies, for a lifetime, and become a participant and witness in those events. All the events that are written in this memoir are true, not only without any exaggeration or embellishment, but perhaps, I don’t know how much I was able to present the terrifying force of the events that took place in that decadent system of socialism, where no there was no human feeling.

Continues from last issue

Zejmeni, near Lezha

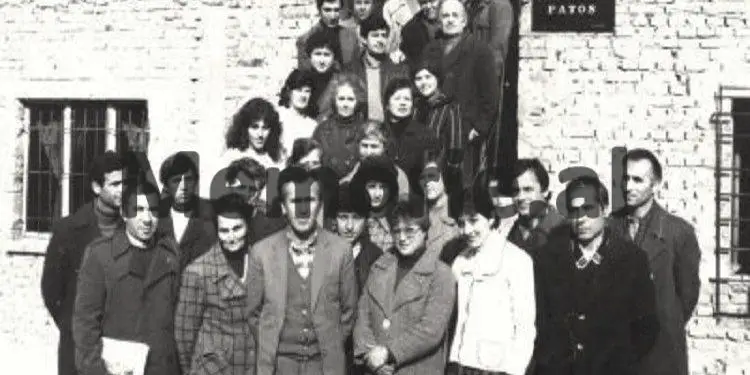

When the auto-prison stopped, as we were, still locked in on all four sides and telephoned by the hallucinatory journey, we thought we must have arrived at the unknown place to which we had been addressed. And indeed, after the doors of this living coffin were opened, we could look at the open sky and be filled with fresh air, but we also noticed that we were in a courtyard, which was in front of a three-story building. The other sides of the courtyard were bordered by one-story buildings. The entire camp was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire, up to a height of several meters.

There were hundreds of prisoners in the yard, who at that time had their walking time. They had dead faces, in a color like white from the lack of sun or the diseases they had, as well as from old age and the heavy suffering they carried on their shoulders, for many years in the prisons of communism. Even more lifeless they made their clothing of dock clothes look, poorly tailored, which made some people loose, while others were tight, all of them ended up on sneakers or torn shoes. They gave the impression of a very large crowd of street beggars who beg for a living.

Over these dock clothes, most of them had also thrown a coat, one of those thrown out of use by the soldiers, but they had already changed their color to dark brown or red. The coats fit the prisoners even worse. In addition to this uniform clothing, they also had in common their haircut, for they were all without hair; or bald, or shaved with a machine without the point of care. So even this feature, which often serves to distinguish people from afar, was already flattened. They all looked the same. Some of them wandered alone, deep in thought, while you often saw lots of others, who were passionately discussing with each other.

For us it was more reliable that all that great crowd of people seemed uniform to us, because we were all strangers to them, just as we ourselves could not recognize ourselves, when after a year, we were given the opportunity to face a mirror. The sight of people with faces killed by suffering, not well fed, tired of life morally and physically and with such clothes, did not allow you to think that among them, you could find engineers, doctors, teachers, priests, lawyers, artists, army officers and intellectuals of all kinds. The outward appearance at first glance devalued these victims of the dictatorial regime, but when you got into the conversations and got to know them closely, you realized the wrong impression you had on the first day.

This was the camp of political prisoners in Zejmen, located very close to the small town of Lezha. Adjacent to this camp were other buildings, which did not communicate with our buildings and which constituted the camp of ordinary prisoners. Both these camps were surrounded by the same belts of barbed wire. This building gave the appearance of a horse stable in the desert, because there were no other buildings around these two camps. On all four sides stretched far away, a large open space.

When we got out of the car, we sat as if stunned, just as small children sit when they get off the bus, in a new environment and wait for the teachers to accompany them and explain the wonders of the country. That’s how we waited for the instructions, where we were going and what we were going to do. At first we were ushered into a small office to complete the registration formalities. Soon after, we were led into the three-story building and divided into different rooms, where there were lots of empty beds. The rooms were large, in the form of silos, and in each lived more than thirty prisoners, placed on double plank beds, built floor above floor, alla sailor.

It is easy to imagine what kind of sleep could be had in such a stable, where mostly elderly people in their sixties slept. A few weeks later, we who had been terrified of solitude, began to hate such intolerable associations. The hall was noisy with the snoring of the elderly and the winter cold, on the other hand, made our sleep look like a black and white film, torn to pieces. Sometimes you were woken up by the screams of other prisoners, who complained or were scolded by their mothers, those desolate old men who snored without being able to control themselves.

Only the beds were well arranged, according to certain rules, with each person having two blankets and two sheets. The mattresses were filled with straw made of wheat ears, to pierce the body. In winter, we put one sheet over the blanket because it made you feel much warmer. The upper sheet prevented cold air from entering the interior. In winter, the buildings were without any kind of heating.

After showing us the place to sleep, we were given the prison uniform, which, as I said, consisted of a jacket and a pair of trousers, two white undershirts, with long sleeves like those of the soldiers, of two pairs of benevrets, which we had to change them from the red coat. This clothing of the ward was relatively acceptable, but still insufficient, especially for the winter period, when we had to go outside for appeals or walks.

The first thing we did in this new apartment was a nice shower, as we hadn’t showered in about three weeks. In fact, we found better conditions there than anywhere else, because the shower room was closed, the windows had glass, and the separate one was heated by hot water vapor.

After a year, it was the first real shower we took under normal human conditions. After the last rinse, a prisoner in his fifties, with partially fallen, partially bleached hair, enters my shower room. His face was covered in wrinkles and they showed a man suffering more than anything else. Suddenly he addressed me by name. -“Partridge”! The voice seemed familiar to me, but I was tormented by his face, which I was not bringing to mind. I focused all my attention and found the one I never imagined I would find there, my childhood friend, work and life friend, engineer Niko Goxhobashi.

We embraced with great longing, like true brothers. He had been in political prison for about eight years. I thought of that big, nimble Niko, with his well-chosen and carefully dressed. I imagined the mechanical engineer that most of the oilmen loved and respected, until he stepped on the rotten board, said that; Pali Miska, member of the Politburo, was not so capable. This was his only “crime”, a crime that led him to be sent to prisons for years, to be chased by the police, and from an honorable name, turned into an appeal number. While I, years after him, had my hands tied and sentenced to a quarter of a century in prison, to admit that he, Pali Miska, and some of his friends had agency connections so that they could be punished from day to day. Oh my God, what was going on in that place?!

Of course I did not tell Nikos about my surprising impression of his appearance, just as he did not tell me about the same. We both barely knew each other. The meeting with Niko made us all very happy, because we found a true friend there, with whom we could talk openly. At first, he told us about some prison rules so that we wouldn’t break them, that we would have consequences of up to a month in the dungeon, and harsh regime, stripped down to our clothes in the middle of winter thin interior.

Then he informed us about some prisoners, with whom we had to be careful not to socialize and talk about political issues, and especially not to cry about our problems, because unfortunately, due to the threats of the Security, they had turned into informers his. We were very curious and wanted to know who were elected members of the Political Bureau in the recent congress, and when we heard the names Nikoja told us, we couldn’t believe our ears!

We were amazed how those people, for whom the scenario of our arrest was mainly organized, for whom we were tortured for months, could be re-elected, and we resisted writing how they were in this direction; “sabotaging dirty work”. We racked our brains for the explanation of this puzzle and cut it with our judgment that the continuation of this scenario would have been left for later, for reasons that we of course did not know. It took us days to tell Nikos the details of the investigative process, the torture, the living conditions, what they asked us to accept and how we were forced to accept it.

When we counted the figures of the Politburo who were in the plans of arrests behind our group, he was left with his mouth open in surprise at these new scenes and intrigues, in the high leadership of the party and the Albanian communist state. He was not at all surprised by the exploits of the investigator, because he had experienced them on his own skin, and had heard hundreds and hundreds of stories of all kinds, full of atrocities. He was well informed with the criminal methods used by the Security and the Enverian investigation, as a way to bring the entire people to their knees, and to keep their fortress of communism, so stained with the blood of Albanians.

In the Zejmeni camp, I finally managed to realize one of the wishes that often kept me awake since the time I was locked up in the dungeons of the investigation, the meeting with my family. The day I saw them after so long remains among the long-awaited days that are so rare in human life. We couldn’t get enough of seeing each other. In the first moments, I read in their eyes my bitter image of an old man, his face whitened by the long absence of the sun, his hair shorn with the camp car, all tangled up in that red coat, above the dock clothes. Suffering had added wrinkles to Janet’s beloved face.

The children seemed older and more beautiful to me, and it seemed to me that they were suffering, but cruel bullets had passed by them, and could not catch them. And this truth was a great happiness. We barely had tears that even today I can’t tell if they were from sadness or happiness. It seemed like we had millions of questions in our mouths and couldn’t get them out. This first meeting happened after a year of lack of information about the health, work and general condition of my family members. There I learned that my daughter, Hilda, who from primary school, high school and university faculty, had kept excellent results. However, the girl was expelled from the university immediately after my arrest. She only had the last two months of her degree defense left and still; they didn’t let her finish it.

This girl, who came to the faculty with a gold medal from the high school of foreign languages, was proposed to stay as a lecturer in the same faculty. But with a special order from the Internal Affairs Department of Fier, the rectorate was forced to order her expulsion from school for political reasons, related to her father’s imprisonment.

Hilda had started wandering around job centers, but no one would give her a seat. Finally, after several years of wandering up and down, she was able to get a job at the Textile Factory in Tirana, as a worker in the loom department. Zhaneta’s sister had adopted Hilda as her daughter, and was able to keep her in Tirana. In those years, from the Textile Factory, they complained that they could not find workers to go to work there, because the technical condition of the machines was degraded, the working conditions were very difficult and the pay was very small.

However, the girl was happy to find that job as well. Newspapers called for young people to go to work at the Combine, but the youth did not respond to the calls. The family’s joy over Hilda’s employment faded very quickly. She stayed at Kombinat for only two months, because the staff fired her again, with the intervention of the State Security bodies, who did not take their eyes off the children of political convicts.

Fier’s security, upon learning that the girl found a job, with vigilance and partisanship rooted in her blood, intervened to remove her from her job, for subtle political reasons. It must be said that the Committee of the Fier Party, which at that time was headed by Pali Miska, had expressed the exile of my entire family, in remote areas. I have not yet found out which body canceled their decision.

In these circumstances, the girl was forced to open, without being noticed, a course with some young people who wanted to learn English. She successfully developed that course in the small house where her aunt lived on rent, which was now taking care of and loving Hilde as her own child. The young people who followed her course loved and respected the teacher who was almost their own age, and they prepared themselves so well that after a not-distant period, when the democratic changes took place, they all entered the competitions that were held held at that time in Tirana for the English language and won. With the small income of the course, she was able to help the family a little in this period of austerity, in all economic and social directions.

The boy, Genci, was in his last year of high school on the day of my arrest. Although he had very high results in lessons and was a member of the national competition of high school students for mathematics, where he stood out among the best, he was still not given the right to study for university. When he was left without school, he was called to perform compulsory military service. He served in the wards without weapons, in those so-called special wards, where only the children of political prisoners were sent. These were wards of the genius and the soldiers only worked there.

They were digging to open tunnels for the army, in very difficult and dangerous technical conditions, without any prevention of technical disasters. Soldiers like my son only had strict military discipline, military clothes, but it was openly declared that they did not enjoy the confidence of the party to carry weapons, with which soldiers are depicted. Soldiers like Genci were simply needed as slaves for hard manual labor without pay. Several times his life was put in danger by the collapse of the tunnel, by the suspicious releases of wagons by enigmatic persons, who could not shoot at the target in the direction of the front of the tunnel, where Genci was located.

Fortunately, he managed to get out early, notice and avoid the impact, so the wagon could not touch him. Thanks to the support of his two fellow soldiers, who were wonderful boys, he was able to withstand the difficulties and survive that dangerous stage for an eighteen-year-old kid, fresh out of high school.

After completing his military service in the engineering department, in the mountains of Elbasan, he continued to look for work in the most difficult places, such as opening canals and construction works, but no one accepted him for work. The goal of the rulers was the destruction of my family.

This was another crime, which was attached to the crime they did to me. The boy was dealing with a difficult situation, which became more difficult with those frequent calls to the Internal Affairs Branch to put pressure on him. Genci went through severe nervous stress, which started with the absence of his father and continued with threats to his life. My family members were completely isolated; it almost seemed to them as if they too were in a prison regime. Under these conditions, the mother was forced to teach her son how to sew pants. He did this at home illegally, first approaching his friends as clients. The instructions were strict: no one was allowed to do private work, and if caught by the authorities, the offender was severely punished. Therefore, Genci did this work with great fear, lest the Security officers find out and imprison him.

Thus the children, under the care of their exemplary mother, with an extraordinary savings regime, were able to live and support me with food. With Niko’s help in the camp, we were able to get to know very quickly, prisoners who had been there for years. It was a real pleasure to talk with them. Some more elaborate, some more simple, they told their own dramas and, as a result, their families’ dramas. They were shocking, painful. All the stories had a common denominator: their innocence. Thus we learned that with the scheme that had been implemented with us, although not in those dimensions and manner of development, hundreds of other prisoners were suffering in Zejme, which showed the ruined basis of the political system in Albania, repression, terror, injustice, lack full of human rights and deep poverty.

Thus, the political prisoners were completely innocent, no matter how you find cases with people convicted, because they had spoken or said any words against the government, against any state authority or official in the district, with deficient skills and corrupt morals. Some had stayed there as victims of their passion, to listen to Western music, or even news from the radio stations of the Free World. Punishments for these causes may seem quite absurd now, but they did not seem so at the time. Memorie.al

The next issue follows