“New York Times”: Behind the Scenes of the Alia-Mitsotakis Meeting in 1991

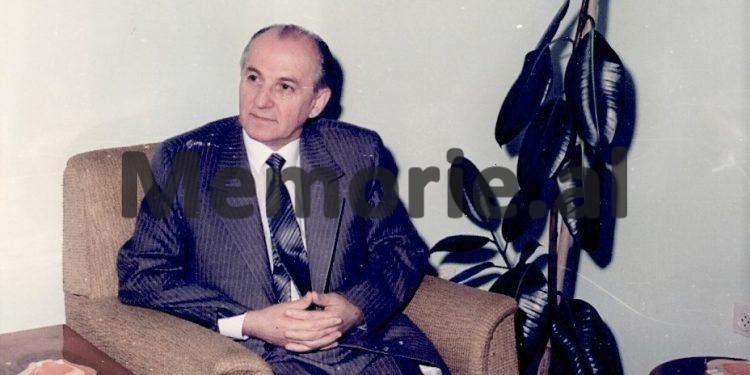

Memorie.al / Today’s talks between the Albanian and Greek leaders have failed to resolve the crisis caused by the exodus of more than 6,000 Albanian refugees who went to Greece. The differences were so visibly serious that the Prime Minister of Greece, Constantine Mitsotakis, the first Western leader to visit Albania since the communist regime was established in 1944, declared that; “he is not entirely sure whether his visit will bring about better or worse developments between the two countries.”

Speaking in the presence of journalists during a somewhat strange public discussion with the President of Albania, Ramiz Alia, Mr. Mitsotakis expressed his expectation: “It is not enough to say that we want good relations, but we must do something about them. And to achieve this, it is simply not enough for only one party to act.”

The Greek Prime Minister’s two-day visit to Albania, in fact, sought an agreement to end the tensions surrounding the influx of Albanian refugees into Greece, the majority of who are ethnic Greeks. Athens has accused Tirana of instigating the exodus to rid the country of a potential minority threat and, through it, to shrink the political opposition on the eve of the first multiparty elections, which are to be held in February.

Greece demanded the formulation of a public stance by Ramiz Alia, guaranteeing amnesty for the refugees and promising their safe return, as well as a series of measures to provide assistance to the ethnic Greek minority.

Greek Demands Are Not Accepted

In fact, the Albanians rejected most of the demands made by the Greeks. Sazan Bejo, a spokesperson for the Albanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said that; “Tirana refused to declare an amnesty for the refugees but will discuss their ‘relief’ under Albanian law. This means they will be penalized only if they left without a passport, a visa application, and an exit certificate – or the majority of them, who will claim they fled from political persecution.”

Bejo also added that; “the Albanian side rejected the Greek demands that a United Nations delegation be allowed to visit ethnic Greeks in Albania; that Greek consulates be established in three Albanian cities in the Southeast, which are largely populated by Greek minorities; and that Greek priests be allowed to perform services in the Greek Orthodox churches.”

Official Tirana responded that; “the visit of the United Nations delegation is an issue that will be requested by that organization itself; that the Greek Embassy here is sufficient, without the need for other consulates; and that the Albanian Orthodox Church is independent of the Greek Church.”

Also, both parties did not agree on the number of the ethnic Greek minority. The Albanian spokesperson said that official Tirana estimated a number of about 60,000, compared to Greek data, which spoke of about 400,000 minority members.

Furthermore, not only was the Greek claim of mistreatment of minorities rejected, but for the first time, official Tirana launched a counterattack, announcing that; “there is an Albanian ethnic minority there.” Greece refused to discuss this issue.

President Alia did not accept the arguments that there was a total failure in the talks. But he did not give details of the announced agreement on any fundamental issue. Speaking in the presence of Mr. Mitsotakis and journalists in his office in the Presidium of the People’s Assembly, he said that; “I will not speak of a failure. I cannot say that Albanian-Greek relations are strengthening, which we all desire, or about the issue of the ethnic Greek minority.” Both sides made last-minute efforts to reach a partial agreement, which was reflected in a joint statement by the two Foreign Ministers.

Although a full amnesty for the emigrants has not been guaranteed, the two diplomats said: “Both parties agree that it is in their mutual interest that the minority Greeks remain in their country, i.e., not leave; and that those who have left can return and continue to live here without any punishment, as free citizens of Albania.”

The Greek Foreign Minister, Antonis Samaras, said at the close of the press conference that “the stance shows that the talks have not been a failure.” He also said that “Greece’s other demands have not been entirely rejected but are still being considered by the Albanians.”

Yugoslavs Forcibly Expel 368 Albanian Fugitives in 1990

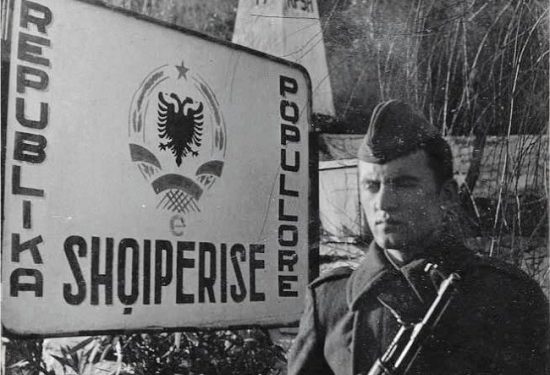

Faced with the increasing number of Albanian asylum seekers and the growing reluctance of Western states to grant them final shelter, Yugoslav authorities in recent weeks have begun to forcibly return all fugitives from Albania, whom the government of the communist state had reported as condemned and who, if returned, would suffer up to three years in prison.

“Yugoslav authorities returned 368 Albanian fugitives on January 30-31,” United Nations officials said today. The group reports that among them are women and children.

Double Punishment for the Fugitives

Western diplomats here have expressed concern that 100 other Albanians are expected to be sentenced to a 30-day term here for illegal entry and may soon be returned to Albania, in addition to those who have previously been with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who were held as asylum seekers until they were sheltered in third countries.

For many decades, Yugoslavia has been a transit point for people fleeing the former Eastern Bloc countries. Such escapes have been decreasing as the new governments in these countries made legal travel procedures easier, but officials here and elsewhere in Western Europe are now afraid that economic poverty and the new ease of emigration could produce an unavoidable surge of refugees seeking a better life in the West.

Albania, the poorest and most backward country in Europe, has been governed by communists so strictly since the Second World War that even now, in recent months, they have closed travel abroad to almost all citizens. Even their requests for permits are reduced before they travel to another city within the country. The recent influxes of fugitives from Albania have been due to the desperate living standards here and a reduction in border control.

Official Tirana Provides No Security

“The Yugoslav government is especially sensitive about Albanian fugitives because it has problems with the Albanian ethnic majority located in the Serbian region of Kosovo,” says a Western diplomat.

“The Belgrade government informed the United Nations High Commissioner on Tuesday that Albanian officials at the border crossing near the city of Titograd, in the Yugoslav Republic of Montenegro, had given verbal guarantees that the Albanians would not be punished if they were returned across the border,” said a UN official.

“This kind of security is not enough,” the official insisted. According to him, “The inviolable principle of refugee protection is that persons are not returned to their country when their life or freedom would be endangered.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees “would welcome security from Albania that these people will not be in danger,” the official said. “But the vague assurances given at the border are not sufficient.”

“We have documented cases from Albanians who recently presented themselves, where some of the returned fugitives have been sentenced to over 3 years in prison,” the official says. Albanian and Yugoslav government officials refused to comment on the return of the Albanians.

The number of Albanians sheltered in Yugoslavia has been increasing in the last 50 years, with more than 1,000 Albanians between 1980 and 1990, and 472 in January of this year alone,” officials say. Memorie.al

The articles were published in “The New York Times” on January 14, 1991, and February 23, 1991.

The titles are editorial.

Prepared for publication by Albert Gjoka.