By Namik Mehmeti

Firenze

Memorie.al publishes the memories of the well-known journalist and publicist, Namik Mehmeti, originally from the city of Shkodra and living for years in Florence, Italy, who brings to the reader some events from the period of the late ’60s, when he served as teacher of Language and Literature in the district of Mirdita, where he had the opportunity to meet Musine Kokalari, the dissident writer who after being released from prison for a long time, lived there during the years of exile. His rare testimony: how his fellow teachers labeled Musine Kokalari, who was the man they had put to monitor him and what was in the package she sent to Enver Hoxha from the Post-Telegraph of the city of Rrëshen ?!

How did I meet Musine Kokalar?

(On the occasion of the 37th anniversary of separation from life)

I only knew him as a physicist, that is, a silent portrait, which even today, after half a century, I still have fresh in my memory. So I got to know him without being able to exchange a word with him, a greeting or a smile.

– Then how did I introduce myself to Musine at a distance?

In 1961, after graduating from the Pedagogical High School in Shkodra, I was appointed a teacher in the district of Mirdita, where the city from the line I was destined by the Ministry of Education to be a support for the development of education in this province.

I, a young 18-year-old, joined an army of teachers who were known as citizens of Shkodra, but almost all of them with “sticks” in their biographies, as I was, as my father had suffered in the camps and prisons of Albania, as an enemy of the people ”.

Remember the surnames of the teachers from Shkodra who came from families with “sticks” in their biographies such as: Sinani, Juka, Hoti, Baqli, Jegeni, Mjeda, Çefa, Shurdha, etc., and who were scattered around Mirdita.

Fate followed me after I heard that I was involved in sports and journalism, and from this I was appointed to the 8-year school, where I taught the language of Literary Reading.

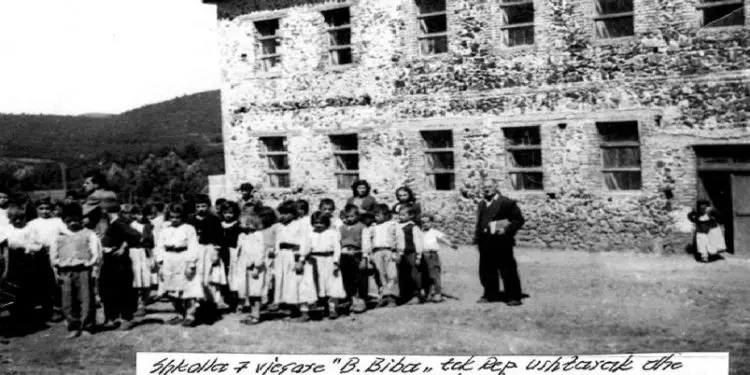

The first acquaintance was with the school, the high school named “Bardhok Biba” was opened. The old school was built on a hill, where the road leading to it was beaten only by students and teachers.

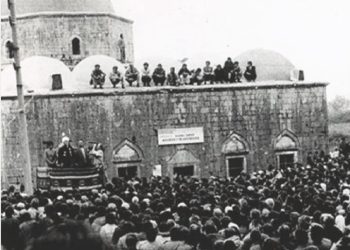

In that emptiness of houses, a building like a silo, with eternity coverings and walls plastered with cement, attracted attention. The deputy director of the school, no doubt from Shkodra, told me that the teachers had lived there before, but since it had become a shelter for the interned families, care had to be taken.

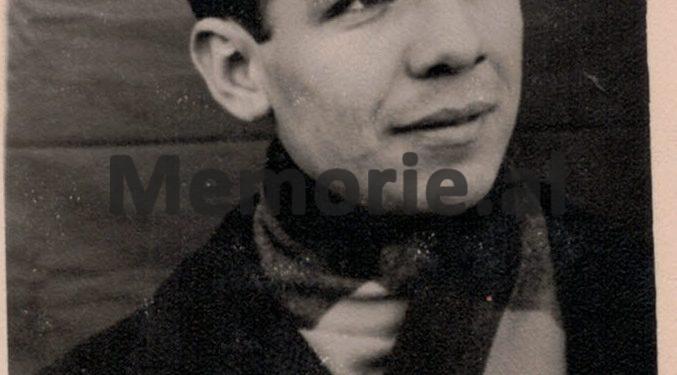

As I spent days on that street, my eyes always focused on the walking of a seven-year-old woman, dressed in the work clothes of a Construction Company, or a Utility Company.

Teachers who knew her instructed me not to greet her even if she approached a greeting with a nod or a smile. “She is a Gjirokastra woman who has spent several years in prison as a declared opponent of the communist regime,” someone told me, and now she was suffering years of internment.

This woman had a special gait, looking only straight, without turning her head either left or right, with a pride of an intellectual, I say without exaggeration: even proud.

Spontaneously after a distance acquaintance, I was interested and curious to learn who was this woman who so bravely ignored that exiled contempt.

No doubt I too had to be careful when quenching my curiosity about her name. A friend of my father who had served his sentence in the prisons of the dictatorship together, lawyer Sabri Quku, who had studied in Turin (since Rrësheni did not have a lawyer, in old age, for survival, had come to work there, sacrificing to support the family), I asked who this woman.

A day later he told me: “She is a writer and inspiration in the first politicians who created the Social-Democratic Party, coming out openly against Enver Hoxha. In her trial she has openly displayed hatred against communism. They call him Musine Kokalari. When you go to Shkodra, you ask your father, Et’hem, that you know him very well as a family, that he worked in the municipalities of Gjirokastra, in the years of the Zogist Monarchy, why not in the camps of the dictatorship. “Every time I meet him, I greet him”, moving the republican hat from his head, lawyer Quku concluded the conversation.

I had heard from my father conversations at home with friends and cousins about the suffering of prisoners in labor camps, swamps and canals, trials by communist prosecutors, the stoicism of Catholic and Muslim clerics, and in between others mentioned the trial of Musine Kokalari.

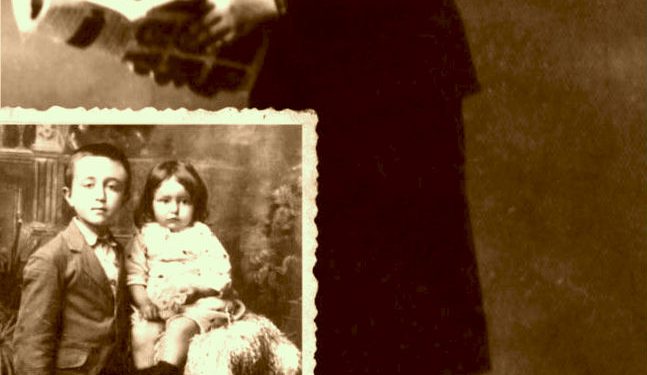

“I knew Musina and her brothers who were shot without trial. A family with traditions and a very intelligent female. “You are surprising me with this acquaintance you have made”, my father told me, not a little surprised.

She asked me about her health, the work she did and her treatment. “Worse than a slave,” was my reply.

I stayed in Rrëshen for five years until it was my turn to go as a soldier. In those five years I also met other internees who were scattered from Shpali to Kurbnesh. Among them is a brave and charming boy from Kosovo, Selim Kelmendi, who worked with his wife, Drita, a girl from Shkodra, of the famous Dani family.

Musine, after two years when I returned to Rrëshen, I found him older, but proud as I had known him in the beginning. This pride infuriated the employees of the Internal Affairs Branch, where she made her presence in this criminal institution twice a day.

I remember one afternoon, when at the city post office I was waiting to talk on the phone with my parents in Shkodra, this woman entered without shyness in a different outfit from that of daily work, simple, but radiated a nobility and a citizen to attract attention . He was holding a bag of meringue, from which he pulled out a package, addressing it to the postman, who was alone in the service that afternoon.

He glanced at the address written with a black pencil and I fixed the name of the address where this package was sent: “Enver Hoxha Central Committee P.P.SH. Tirana “.

The centralist looked scared, this package with that address. He put the plugs in and connected to the Inner Branch. I was pulled from the counter and only heard the answer given by the centralist:

“You mistyped the address. It should be written: Comrade Enver Hoxha ”. I did not hear her answer, but after the centralist used the chips once again, I do not know with whom he communicated, but the answer was: “Leave the package here and tomorrow look again and get the answer”.

I heard that a safe was opened and the package was placed for safe storage.

The centralist approached me after the line with Shkodra and I then approached him to pay the telephone call fee, he did not ask what Musine Kokalari would post at that address, he told me: “It was a book, until he went to the address of written in that package, the party in how many hands it will pass ”.

I was surprised by these words of the centralist, whose name I have now forgotten after half a century, but I remember that he was a night school student in those years.

Seeing that I was not showing any curiosity, he spoke again: “However, what I told you, do not talk to colleagues.

With a nod of my head I approved of the order and left the post office for the House of Culture.

On the occasion of the 37th anniversary of her death, I remember as today her portrait, that walk in solitude, the sidewalks and streets of Rrëshen with a stop at the bakery or grocery store, and then the hours of solitude in that house, only home was not where she spent her years until August 14, 1983.

That house full of damp, that shovel and pickaxe, that life in the dark approached his untimely death, without even the slightest medical help, even though the hospital was not more than 100 m away. from Argjiri’s house.

They called that house that, because the only chef of the restaurant of Rrëshen lived there. I remember he was a Greek miner from Saranda. It was her surveillance.

Even today, when I remember those episodes that I described, the portrait of the writer and anti-communist Musine Kokalari, I still have in my memory, as well as that house of Argjiri to express fear with her gloomy appearance, the gloom that Musine Kokalari challenged with her intellectual and democratic spirit./Memorie.al