By Niazi Nelaj

The twelfth part

Memorie.al / Expelled from the Soviet School of Aviation, with dreams cut in half, part of the group of student pilots, who had studied for a year in the city of Bataysk, on January 8, 1962, after a “hell” cruise ”, with a cargo ship, we arrived at the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School in Chin Zhou City. It is located in the “heart” of Manchuria; at that time there were about 200,000 inhabitants. Without any prominent industry. A city with 2-3 story buildings but paved roads. The terrain around the city was plain; next to it are the Western shores of the Yellow Sea. One of the values of this city was the fact that it was the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School. My going to this school and that city was a lucky chance. In the list of 7 students of our course, which included: Adem Çeça, Dhori Zhezha, Mihal Pano, Bashkim Agolli, Andrea Toli and Sherif Hajnaj (Bracki), my name, Niazi Nelaj, was included, quite by chance?

Continues from last issue

-At the Chinese Military Aviation School-

The delegation had returned to the Motherland; Gogoja, for reasons we couldn’t find out, was separated from his current friends, he had to return to Albania with us. He was about 35 years old, with a fit body and a smiling nature. He spoke the Bulgarian language well. In Bulgaria, Gogoja had studied and in Bulgarian he communicated freely, just like us who spoke Russian. We burst out laughing when we followed Gogo’s communication with our translator. Gogoja in Bulgarian, Russian translator; they got along, for beauty.

I’ll say it from the beginning: Gogoja was a mature man, without vices, kind, prudent and cultured. We were younger in age, but he listened to us and played with us as if we were his friends for many years. long ago. As I can express it, as they say in our country: “Gogoja was cut with elderberries”! As a member of a government delegation, the Chinese had treated Gogo fairly well economically. After his friends left, they had given him all the diet money, which he had spent on buying gifts for his relatives. He joined our group when his pockets were empty. He didn’t even have money for food, let alone for other economic needs.

We, as pilots, were fed well, in quantity and quality. We felt sorry for Gogo, so we often invited him to our table, generously. Soon Gogoja became the “sixth pilot” of our group. Before us, in that tourist town, the officers of the group were organized, expelled as protesters, who, despite the economic treatment not in accordance with the laws, had refused to fly. Along with them were some students declared as disabled, for various reasons.

One of these students was a tragic man named Xhavit Kabella. I knew Xhavit since Batajsk because he was in the same group of students but was rejected after a medical test. It came before me again, here in distant Cajgon. He was, neither more nor less than a “wedge in the sun”. Mentally retarded, with a level below that of his group mates and with character defects. I remember the moment when the Russian teacher, in Batajsk, asked him about the portrait of Maxim Gorky, which was hanging on the wall. Xhavit replied that it was Stalin’s portrait. Our teacher was surprised, while we who knew Xhavit, what a miss he was – we laughed.

Even here, in China’s Cajgon, Xhaviti, not only had not changed but, with his unprecedented behavior, shamed us. He used to go to the huts of the peasants around the town and steal the eggs of the chickens. It was not the lack of food or the improvement of the diet, with the eggs that Xhaviti grabbed, that the food was plentiful and of good quality; it was only a matter of satisfying his philandering habit. The misdeeds of our friend did not go unnoticed by the locals, who laughed it off for the sake of friendship. We found “ready” this negative opinion, which we covered with our correct and cultured behavior. With difficulty we created a new, sound and deserved opinion. Xhavit’s behavior remained isolated and lonely in front of our attitude. On the morning of April 11, 1963, we boarded the ocean liner “Vlora” and left for the Motherland.

The way back to the homeland seemed shorter to us

We couldn’t wait for the ship to go out into the open sea. We were not expected to leave. When we heard the siren of our ship and those in the harbor (the sign indicating the departure of the ship), our hearts skipped a beat, louder than the roar of the siren. Finally, in the tired eyes of my companions, I saw the brightness and vivacity of age. The ship “Vlora” was more sophisticated, compared to the ship “Durresi”, with which we went to China. Sailing with the ship “Durrësi” made us gray and bored us that interesting trip.

The ship “Vlora” was manufactured in Italy; equipped with a powerful diesel engine, which delivered 18-20 nautical miles per hour. They were accommodated on the ship as sailors, but in better conditions than those going to China. The crew of the ship with Captain Haxhi Shehu, chief engineer Berti e long; Doctor Zyber Mukë and full of good people, they treated us like friends and old comrades. We spent most of the day on deck. Our hearts were happy and we jumped up, like children, when we noticed that our ship, “racing” in speed with the other ships of the navigation corridor, passed them and left them behind.

We were happy that we had the good feeling that we were getting closer to our Albania in time. We felt the smell of our beloved country, even though we were many kilometers away, in the sea. In everyone’s eyes, it was clear the longing for parents, brothers and sisters, offspring, for all those who knew them and knew us. We missed it. We noticed the impatience in every attitude and every action of ours.

The sea routes we passed, the ports and cities that appeared before us or those where we stopped, the beautiful nature that appeared to us, which was constantly changing, did not fill our minds. We looked at them but not with interest; we were indifferent to them. Not only that we had passed them in the past. We had our minds elsewhere. Albania had turned into our mind, into a giant magnet, whose strength disconnects all the instruments of our orientation. I had the feeling that longing for my people and my country overcame all affections.

On the marked day of May 1, 1963, at 7:30 in the morning, our ship “Vlora” with which we sailed for 20 days and nights, through seas and oceans, anchored at the Western quay of the port of Durrës. Her entry into the quays was greeted with sirens of triumph, according to maritime tradition, by all the ships that were anchored and those waiting for their turn, in the queue. It was a day off, the traditional workers’ holiday, but the port people were working. As a rule, even though we were hurrying with impatience to touch mother earth, we were not allowed to disembark without passing through the customs of the port.

We came from far away; we were returning from China, from an Asian country, and although the two countries were bound by unbreakable friendship, in our miserable baggage there could be items, which, in Albania at that time, were forbidden to circulate. I have said it above: in our country at that time, even gambling cards were not allowed to circulate. And what could be inside a student suitcase? With the money we received, we smokers barely had a cent to buy symbolic gifts for our loved ones. However, we obeyed the rules and went there where they told us; from the customs office.

In China in those years, contraceptives were sold in every store and were so cheap that some saleswomen gave them away in restaurants. In our country, they were used only in health institutions, with the recommendation and under the supervision of the relevant specialist. Two relatives, who had many children and did not want to give birth to others, had ordered me to bring them from China, such means that prevent pregnancy. I raised the issue with my Chinese friend, the “gold” translator from Uyghur, Petjan.

I smelled the trick of the customs officials, who extended the control to the private parts of the body, so I left the contraceptives with a sailor from Durrës, with whom I kept company during the cruise. Durrsak, young, with a slim body, short stature and curly hair, quite energetic, good mechanic, not only took the order out of customs, but brought it to me in Tirana.

The sailors, during the voyage, had informed us that the customs officials are specialized and know all the possible tricks of the foreigners. They also check your body, the sailors we took as friends told us. I thought of the trick I would use to pass a pair of kapron playing cards that I had my heart set on. Tricky customs officers, you could only get away with tricks. I found the way out but I kept it to myself.

The trick was simple but effective. I split the playing cards in two and put them between the socks and the leg; their halves on each leg. I put on the beautiful, wedged shoes that I bought at the Beijing exhibition. The shoes were wide and covered me with all the forbidden objects. One by one, we were ordered to go to the room where we would undergo the strict customs control. It was my turn. I was not without emotions.

The customs officer, a middle-aged man, with a small body and a dry head, with a little hair and with myopic glasses on his eyes, with a “gentlemanly” shamelessly said: “Sorry for the inconvenience, but it is our rule to check you even in the body”! I knew that this was how the poor man had been instructed, so I answered: “Whatever the rules, I have no objection”! I was convinced that the customs officer would touch my privacy, putting his hands even where it is not shown.

I hoped that my trick, as if I were one of those old Chinese magicians, would not be caught by the experienced clerk. My trick turned out to be useful. The smuggled goods were not dictated and I, with slow steps so as not to dictate the secret to me, left the corridor where they would “insert their hands”, according to the law. Neither of my friends, the “strict”, and customs control did not stop any item (I can’t say goods)!

We came to Tirana with a Ministry of Defense bus. I took shelter in the family of a relative of mine, in New Tirana, who, at that time, was an employee of the State Security. In his house I was welcomed and, as was the found tradition of those years, in a relative’s house, I entered without knocking. The next day, May 2, 1963, together with my friends, we appeared at the Ministry of Defense. We were welcomed by an employee of the Personnel Directorate of this ministry and a representative of the Aviation Command.

Until the documents were completed, for our appointment and promotion as officers of the People’s Army, they gave us the salary of a simple pilot (companion) and 1 month leave to go to our families. The representatives of the state, those who received us, informed us that, when we returned from leave, we would not report to the Ministry of Defense, but to the Aviation Regiment of Rinas. They gave us the preliminary designation: fighter-bomber pilots and the department where we would go. All five comrades, as we came from the Aviation School, did not separate us. This must have made us happy.

I stayed 2-3 days in Tirana; I walked around the city that I longed for. I met and talked with my relatives, the next day, by train, I left for Fier. The passenger train used to go to Fier. I slept that night in a hotel whose name I do not remember. The hotel was on the highway that leads to Qafa e Koshovica and further to Levan. The hotel employee, a polite and cultured woman, treated me with fairness and kindness.

The next day, early in the morning, I left for Kraha, via Mallakastra (it was the only car road), in a lorry, ostensibly passenger, equipped with wooden benches, thick and covered with raincoats. It resembled military trucks. The truck driver, a middle-aged barman named Kamber, was on the road practicing law. He stopped the truck whenever and wherever he wanted, took anyone who reached out to him in the car and had a pocket full of money. I didn’t see any police stop him on the way. The highway ended in Krahës (center); further you could go to the village on foot or on some domestic animal.

I arrived in Kraha (center) at noon. I had to travel another 1 hour, on foot, to reach my home. In my hand I carried a suitcase as light as a construction but filled with gifts. It was heavy and at that distance, I could not carry it in my hand. A fellow villager came to my aid and loaded my suitcase onto the donkey’s saddle. On the way to my village (Ahmetaj), which winds through a system of hills (goat road), I exchanged words with many fellow villagers, adults and children.

The children, who had just finished that day’s lessons, in the only school in the village, which is located at the top of the bank and dominates the eight districts of Kalivaç, opened the way for me and greeted me with the phrase “good morning”, raising their hand right side up, as the pioneers greeted at that time. I didn’t know many of them, but I returned the greeting, friendly, with a lot of love. The older ones, most of whom knew me personally, stopped, hugged me; I had to answer their many questions.

It was late evening when I arrived home. I found the mother and father outside, in the yard. Each of them was sitting on a sofa. The only brother, Dilaveri came a little later. His father had charged him with the task of bringing the flock of sheep home. Missing, like me and both my parents, we hugged and couldn’t tear ourselves away from each other’s arms. I went inside and sat in the right corner of the ground floor house, on a stilt, with flowers, which my mother had woven by hand.

Before the exchange of greetings and unfinished questions-answers, as usually happens in these cases, the house was filled with women and a little later with men. They were all relatives who had learned of my arrival. First came Hysnija, whom we called Ninija. An old woman with manly features, originally from Kolonja e Gjirokastra. After her came Tajanja, the ubiquitous mahalla, and Memja, both my mother’s age.

Then came Nefizeja, Xha Lazja, Muharrem Kamberi, clever and sharp, from the mind and from the mouth, Hyrija, Hatemja, Samoja, Zonja e Vogël, Loloja and many others. It seemed as if the women were competing with each other; who met first, with me and who asked first. They had no notice that I was coming that day, but, as soon as one saw me, the announcement spread by word of mouth, with the speed of rumor. Congratulations “poured out like a river”; mother was waiting for them. When the children arrived, the father “stepped into the role”.

After he arranged them, in the hut near the house, with his generous spirit prominent, he did the habit that the incident required. The shepherd, known throughout the land, as he had the tradition, caught a drinking lamb, the best of the lambs, the one he had bought for me, which was born as early as January, slaughtered it and killed it, in the middle of the barn, paved with stone slabs. He didn’t grill it, as he usually did, because he was afraid that the milk fat would melt, but he roasted it on his hair. It tasted the same, as if it had been roasted on a spit. That night we woke up.

The days that followed could not extinguish the longing accumulated by my long absence. A year and a half, without receiving any news or letter from me. The visits, the invitations, the feasts, did not allow me to completely get used to the members of the family and the tribe. I had to visit my loved ones. I paid my first visit to my only sister; Happiness. Longing had burned Lumen; as a sister burns for her brother, especially when she is away and exiled. Then I went to aunt Sherina, in Zhulaj. You need an aunt a lot, especially when you haven’t known her. To that virile woman, the inhabitants of the village said: “You are the mother of the village”. She deserved this office, that woman, for her judgment and for that very human behavior.

During the days I stayed in the village, I did not leave a single house without setting foot. I had been absent for a long time and in every family, something had happened. Someone had a wedding, a second child was added, another was engaged, someone was released from the army, some family had a disaster, etc. Life has and loves it all; like joys and sorrows. I had to go, willingly and happily, without being forced by anyone. Love and respect for people was the motive that made me find myself near those good people.

After a month, I returned to Tirana. Together with Andrea Toli, Adem Çeçë, Dhori Zhezhë and Nipçë (Bashkim Agollin), we went to Rinas and appeared in the office of the Regimental Commander, the glorious Niko Hoxha. The authoritative colonel received us, cheerfully and welcomed us. The unforgettable Niko Hoxha, the “father” of Albanian Combat Aviation, was happy that the pilots he loved so much would be added. With a smile, the colonel introduced us to the task and the regiment he commanded.

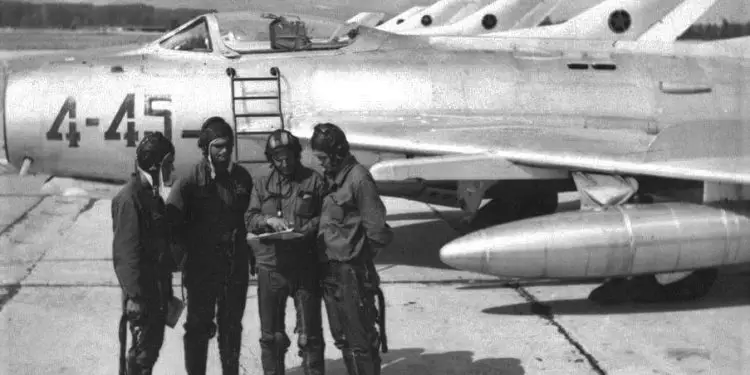

He gave us the good news that we had been promoted, second lieutenants and appointed fighter-bomber pilots in that newly formed regiment. We would all line up in the second squadron and fly the ‘Mig-17 F’ planes. The second squadron had 12 such planes, new, with full resources. The commander of the squadron was the talented pilot, from Vunoi Kosta Neço Dede, with the rank of first captain. The squadron’s deputy commander was the second captain, Gëzdar Riza Veipi, another talented pilot, originally from Picari i Gjirokastra.

The regiment was “hungry” for pilots and couldn’t wait for us. Without being equipped with an officer’s uniform, we started to fly. They provided us with overalls and on our feet we wore sneakers, as we came from China. We were not equipped with an officer’s uniform. Day by day, things flowed in their bed and we were quickly integrated, in that environment and in that interesting team. We were of the same race and we knew the job.

We acquired the aircraft unknown to us, the Mig-17 F, relatively quickly, without having the training variant, which came to the regiment long after. Before many days passed, we “enjoyed” being on combat alert. Initially as the flight leader of the guard couple, after we flew, we entered the formation, in the role of escort. Memorie.al