Jovan Koço Plaku

The history of my father

Firstly, I want to tell you who my father was. I want to tell you that my father was a geological engineer profiled in oil industry. He studied in the Soviet Union in the ‘50s, he was one of the best students of the time, he graduated with excellent results, he came to Albania and worked in the research sector, he was not a man working in an office, but he was a man of science working in the field.

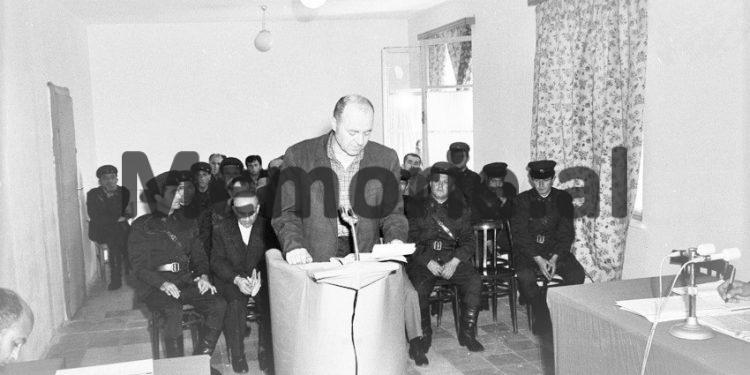

My father was convicted of sabotage and treason against the homeland along with a group of engineers in 1976. It was not sufficient only the charge of sabotage for the persecutors. They had to make up that “sabotage on behalf of the Soviet security agency”. He was a man with strong professional contributions known worldwide, therefore they could not charge him for sabotage. Nevertheless, the agency’s activity is something mysterious, secretive. You can charge it to anyone. The oil sabotage group, as a member of which my father was convicted, consisted of eight people, where two of them were executed and the others were sentenced to imprisonment …

My childhood

I had been impressed since I was a child, but even later, I had been impressed that the connection with the Soviet agency was made because of an episode that had been linked to fishing hooks. My father was told that “we have proved that you had been an agent and saboteur, because in 1966, your acquaintance Elvira Babiçenko, who was from Dhërmi, married to a Russian citizen, she brought you fishing hooks from the Soviet Union. Along with fishing hooks, you also received the orders to sabotage. In fact, my father was passionate about fishing.

This episode of fishing hooks had been stuck in my mind, because in the way that a child absorbs events, especially the events that impress him a lot, I made a connection between the fishing hooks at that time with the word “sabotage” and I considered a very serious thing both of them. Both of these words made me feel connected so strongly with this moment, after such an episode, so that, in order to understand what my father had done, I felt the need to get into fishing. I started to study fishing, I started fishing and I started to make fishing hooks. I made the first hooks with head needles and a kind of thread that my mom used in order to embroider. They called it “Muliné” (“Mouline”) and they said that it was quite strong. At that time, I saw myself as a saboteur too. I had sabotaged my mother’s embroidery. Only that my mother did not punish me. This childish sabotage activity left me with the passion of fishing.

My family

My father was a member of a persecuted family. There is nothing unusual, special, here for all those who know the history of communist persecution, the communist dictatorship. Those who were persecuted were usually persecuted as a family. Perhaps unusual is the degree of persecution imposed on my family and perhaps even the reasons of such persecution. My family is a patriotic family, documented and valued as such for my parents, grandparents and even earlier. The persecution of this family by the communist regime began before that regime had been installed in power. It started in 1944, when the oldest brother, Jorgo Plaku, who was a partisan, one of the first partisans in Albania, close to Enver Hoxha and translator at the Anglo-American missions. He was killed on 7th January 1944 in mysterious circumstances, during a march and, after the war, he was proclaimed “Martyr of the Fatherland”. Later, there were indications which showed that such a murder was committed directly upon the orders of Enver Hoxha. Then, the persecution took over all the brothers, one after the other, and according to the history we have lived, this happened because they had begun to discover the mysteries.

A member of this family was also Kalo Plaku, a former director of the Sukth agricultural farm, the largest in Albania at that time, who died in May 1957 as a result of poisoning. It was confirmed that he had been poisoned by the state security. The other brother, Panajot Plaku, who was a minister in Enver Hoxha’s government, escaped because he felt that it was his turn to be eliminated, despite the fact that even in emigration he did not manage to escape from the state security. Then, it was my father. The rest of the family certainly did not get away, but they suffered the ordeal of internment, eviction, etc. Nevertheless, they still survived.

The stories of families persecuted during the communist regime in Albania are not widely known by society today. They are stories that are told to each other in close family circles. Where there is interest, special programs are made, but the process is only sporadic and not structured, organized and inclusive. It has not yet become a proper policy of recognition, appreciation and education. Stories of communist persecution, as far as they are told, satisfy social curiosity, but they have become neither educational models, nor pillars of social morality.

The professional aspect of my father

My father was a student with excellent results, he was deemed a student of excellence in the Soviet Union. He came back to Albania and for the sake of truth, he was also appreciated as a specialist in Albania, because he was given the opportunity to work in his profession, even though that profession was not a luxury, but it was quite difficult, it was a field profession. My father was in the group and probably the protagonist of the new oil exploration school in Albania, which broke the taboos of the time. If until then in Albania it was said that oil is only in sandy areas, my father insisted before all scientific groups of the time and he managed to convince not only scientific groups, but also political decision makers, that oil in Albania is deposited in limestone, whereas it has migrated from limestones in sandstones.

Something must be understood. I am not a specialist in that field and maybe none of us here is a specialist in that field, but I believe that you all perceive that in the conditions of a dictatorial regime, not only to break the taboos of scientific opinion, but also to risk so much by using funds to substantiate your theses, it was a very bold step, which in itself could lead to persecution if you failed. You could not gamble there. Gambling was with life. And my father had so much patriotism, so much devotion, so much security, so much passion for work and so much scientific certainty, that he was determined to play with life, to prove the accuracy of his theses. He achieved this with the discovery of the Gorisht oil field, the first important source of oil in limestone.

My father was convicted for sabotage. This was the charge worded for the man who had given Albania an incalculable, unimaginable wealth, which had not been given to it neither by foreign assistance. To put it in the language of the honorable deputy, Mr. Baftjar Zeqaj, who is also a geological engineer profiled for oil exploration in the field, who despite being from a younger generation, who had studied the works of my father, who had known him in professional and theoretical aspects, not personally and who has stated that “… in Albania there is no one else who has contributed to the state budget more than Koço Plaku …”. My father did not give Albania his assets (he had no such ones). He had the knowledge and he turned it into wealth. The field of Gorisht has been exploited for 60 years and it continues to be exploited to this day. Other fields as well. Foreign companies, which are present today in Albania in the field of hydrocarbons, continue to use the knowledge and contribution of Koço Plaku in oil exploration, such as: drillings on Shpirag Mountain from Shell Company or other oil areas still untouched, have relied entirely on his studies.

This biography, would be admirable for everyone, not for the fact that he is my father. People come to life to give something to society. This is the sublime role and motive we have in society. All of us. But not everyone has such an opportunity. Not everyone has the same opportunities. Not everyone succeeds. But the people who succeed and succeed in such dimensions, deserve respect, deserve gratitude from society and the state, deserve to be celebrated.

What is the situation today with public gratitude for the contributions of the persecuted persons? People like my father are honored and respected in the circle of people that have known them (not just family members) or in the circle of people who have worked with them, but not beyond that. Gratitude does not extend to public authorities. It has rarely happened that they have this category of persecuted in their minds, or “on the list”. Gratitude neither extends to uninformed groups in society, to those who do not have specific information about the field, but who normally should have information about the contributions of individuals to society. As they have information about the names of partisans, as they have information about the names of patriots, as they have information about the names of prominent footballers, as they have abundant information about the names of singers, composers and especially about the names of politicians. This does not happen, it is not, it has never been. I think it should have been involved in state policies. It should have been in this way not only for my father, but for a long list of those people who have had the same destiny as him.

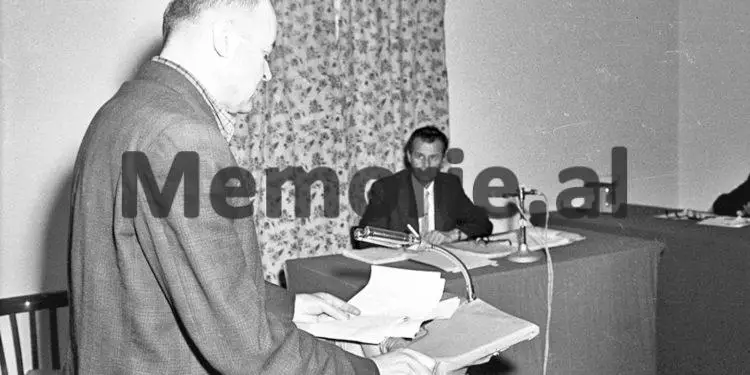

Investigation

My father suffered for about a year and a half in a severe investigation. As I have read from the file, I have been able to understand a lot from the whole series of events. He faced with stoicism charges of sabotage, cooperation with foreign security agencies, treason against the homeland, all forms and types of pressure for a year and a half. They tried to put pressures like “we will destroy your family” to break him, even using his child, myself. I was 1 year old, and I had just started to speak and I had said the first word “father”, in the prison yard, where they had forced us, my mother and me, to go and he would see us from the cell window and be broken by our appearance and presence there. He stood firm, as I read in the investigative file, determined to deny the allegations because he was clear about the trap. The charges had nothing to do with his activity because his activity was enlightening. The charges were linked to the regime’s need to purge a family member who had been placed in the circle of persecution. Apparently, he had understood this, he knew that there was no other solution and therefore he strongly resisted all the offers, both the good and the bad of the Albanian investigation, of the Albanian state security. His file was voluminous, about 5 thousand pages. All the data in the file are fabricated, it is even easy to understand the fabrication of the file, and the technique that was used, from wiretapping, introduction of spies, provocateurs in the cell, breaking the co-accused and using their statements to charge my father with guilt, in the sense of accusation. All of them are clear. It is a huge file, it is a file which is worth studying and from which, scholars can draw excellent conclusions to do the radiography of communist persecution. But even this folder is not a specific folder. It was not just my father with such a file in that regime. Out of the desire and need that I had to understand my plight and to go towards the revelation of my father’s truth, I needed to go through the archives. I have seen many such files. Today, I can say that all these files have a real study value. But, today, with some rare exceptions, with the exception of some individuals with strong will, they are all out of the attention of Albanian historiography, while very good generalizations can be drawn from them and a very good radiography can be made of the communist dictatorship and communist persecution, methods of communist persecution, which would be very valuable to society today in order to understand the past. To make the elaboration of the dictatorial past. If we start from today’s point of view and look at the experience of other countries, the experiences of other countries are amazing. For example, it is amazing how Germany has operated on the elaboration of Hitler’s past and the elaboration of the communist past, in its communist region. In both cases it is a model. They did not let the files get dusty. They did not argue with the reasoning that it is better to keep them closed, because social conflicts may be created. They nourished their people with the amble awareness that without understanding the mistakes of the past, the guilt of the past, we can have no security for the future. And the guilts of the past are understood not by saying “you’re all accomplices, all accomplices”, not by saying “it is better to close them because social conflicts may be created in Albania”, but by saying “we need to understand, we need transparency, we need to be enlightened, we need to learn”.

My story ….

I started to do research. Not because of any particular passion for history. I have another profession and I am realized in my profession. Thanks to my dad’s story, I’m a passionate fisherman and I prefer to spend most of my free time with fishing. But, I chose not to do this. I chose not to pursue my passions. I chose to follow my destiny. And my destiny is to discover the past, in order to see my future clearly. Above all, I needed to know my father, whom the regime never let me know. I needed to understand why that tragedy happened, why the regime took my father’s life. After that, I needed to respect, honor, and celebrate his name. It all started with trying to find his remains, which in any other country would seem like a pretty simple thing, a routine process. All countries, whether dictatorial or democratic, are bureaucratic states, they have this in common. For everything they do, they leave a mark. In Albania, the issue has become difficult not that Albania had not been a bureaucratic country, but the traces were hidden. And I have fought in a long-term struggle, to discover and rediscover the erased traces. I searched the archives, I found the execution documents, I identified the people who were on the execution team and the other attendees, I tried to find where those people are today, to identify them and to approach them. This has not been an easy process at all. I had to do extraordinary maneuvers to get to this point. I had to find people, I had to contact them in different ways, I had to make friends, I had to sit, eat, drink and get drunk with them, dozens of times, so that they could have the assurance that I was not near them to take revenge, but I was near them for my need, for the sole purpose of finding the remains of my late father.

The state should have removed from the backs of the families of the executed persons such a process, the least it could do. Regardless of the regime, dictatorial or democratic, the state is one and this obligation belongs to the state, the state should have fulfilled its obligation to give family members the remains of their loved ones. This should have also happened due to the fact that a state that does not respond to this obligation is a state that does not have the will to show remorse. Repentance also belongs to the state, not to the regime.

I have privately taken my initiative to dig. I rode myself on the excavator to dig, though I am not an excavator, though I am not an exhumation expert. I do not know this field. But I and many other people, who were in the same conditions as me, had to help ourselves, because otherwise, no one would help us. We did this work and to some extent we managed to discover some sites where the convicts were buried following shooting and as shown by the chronicles, we managed to discover some remains and we took them for identification to forensic medicine. There are many people who have dug in order to find their relatives, who have found remains and reburied them without any examination. There are others who have done DNA tests and after finding that the remains do not belong to their relatives, have thrown them away. There are others who have accidentally found remains at various execution sites and have destroyed every trace.

My situation today is this: I still cannot say where my father’s remains are. I still cannot rebury them in a dignified manner. I still cannot give my father the grave he deserves. I still cannot visit him on the day of his birth or murder, to commemorate him as he deserves. Because I lack help from the state, in order to identify among the multitude of remains we have found, which are the ones that belong to my father and which are the ones that belong to his co-executed. The state is still not meeting this need.

When we found the remains at the foot of Dajti and the story became public, Serbia made a fuss and claimed that the remains belonged to the victims of the 1999 Kosovo war, to Serbs whose organs were taken for trafficking. I know that this propaganda was so strong that representatives of the UN came to Albania to conduct investigations. The Albanian authorities still remained indifferent, when the charges could be dropped immediately, if they completed our request to do a DNA analysis for the exhumed bones. Even nowadays, perhaps the internationals are convinced that this issue has no relation with Serbia’s nonsense, but Serbs can still claim it, although we know for sure that they are the remains of our relatives. We just do not know which ones belong to my father and which ones belong to his co-executed.

Rehabilitation

In the case of my father, the example of rehabilitation is the example of how society has rehabilitated a member of its own, for whom society has felt that he was a victim of communist terror. Today, a statue of my father has been placed in Patos. This statue is the contribution of the people who have known him, the contribution of his achievements and of the people who have respected his contribution, but not of the state. That monument is entirely the product of a private initiative, which has definitely been approved by the local authority, but the initiative was all private and the celebration is all private. I am very grateful for all this, especially to the deputy Baftjar Zeqaj, who has known, appreciated and truly respected Koço Plaku, as we, his family, have done.

Rehabilitation is a big topic and a topic which needs to be taken very seriously. Rehabilitation does not bring people back to life physically, there is no possibility. Nature does not allow it. But rehabilitation brings the memory of these people back to life. Rehabilitation is not mythization. Rehabilitation is recognition and appreciation, with the good and the bad that people have had. I can say this easily because my father, because of his life story, has had the good, but not the bad. There have been contributions, but not damages, while others, who have triggered damages more than contributions, find it more difficult to seek rehabilitation, because rehabilitation means that society recognizes the damages as well. The important thing is that we as a society should not go towards mythization of the characters because of the need to suppress superficial curiosity. This is not rehabilitation. Superficial curiosity does not bring people back, it does not rehabilitate them.

Reintegration

Reintegration has been widely welcomed by the persecuted. But it has been considered as a deeply materialistic, sometimes cynical process. The state did not create a complete database, but these people have to submit a mountain of documents to the Ministry of Finance for each of the compensation installments, otherwise “the funds are burned”. Meanwhile, the state has not thought that reintegration is also spiritual, not only material. In a certain way, reintegration has been seen as a set of measures aimed at “closing” the mouth, but not healing the wounds. The wounds of the relatives of those executed by the regime will remain open, as long as the ordeal of our executed loved ones has not been closed yet; their remains cannot rest in peace and we cannot remember and honor them like any another man who remembers and honors loved ones departed from this life.

I wandered so much around the hills of Tirana and dug so much that from time to time, I got into a dilemma, I said to myself: “Is somehow exhumation becoming my passion?! My passion is fishing, not exhumation and sometimes, I felt the need to go anxiously to the sea, to catch the hooks and go fishing, because I had to compete and choose between passions … ”./Memorie.al