By Vasil Qesari

Memorie.al/ The overthrow of the great totalitarian edifice in Albania would leave behind, not only the change of the system, accompanied by lots of hopes, mirages and cries of happiness but, unfortunately, also many wounds, dramas, victims, dust, milk and disappointments from the most different. Ten years and more after that event, which deeply shook society, completely overturning many previous codes, rules and concepts, people still continue to ask themselves such questions as: What really happened in society Albanian, during the last 50 years of the dictatorship? How was it possible that the system managed to warp everything? Why did people accept it? What was the totalitarian logic of the transformation of society and the individual? How were the structures of totalitarian mechanisms conceived and functioning: propaganda, secret police and the exercise of the ideology of terror? How did it happen that among all the communist countries of Eastern Europe, Albania was considered an exception or a special case? Why did Enver Hoxha remain blindly, fanatically loyal to Stalin until the end, turning the country into a prison where violence, fear and purges continued until the end of the 80s? Why was the country so insanely isolated, locking people up between bunkers and barbed wire? Why, then, did all the above phenomena happen…?! The book “Post-scriptum for Dictatorship” does not claim to provide definitive answers to the above questions, or the complexity of the reasons that brought and maintained the totalitarian power in Albania. Nor is it a complete, deep and comprehensive fresco of the life and suffering that people experienced during that system. Its author, perhaps, has the merit that together with the retrospective view of the totalitarian period as well as the zeal of a passionate analyst, he has tried to turn his head back once again, to give not only his personal memories and opinions, but also to return once again to the vision of that era with the simple philosophy of preserving the Memory and supporting the Appeal to never forget the well-known maxim, that…the corpse’s nails and hair continue to grow even after death! Ten years or more after the great revolution, the book in question has current value and we hope it will be appreciated by the reader because, as an Albanian researcher also says… the greatest evil that can happen to a people comes when he fails to analyze his own past. An amnesic people are forced to be constantly neuropathic and repeat their painful experiences…!

Continued from the previous issue..

PROVINCIAL CHRONICLE

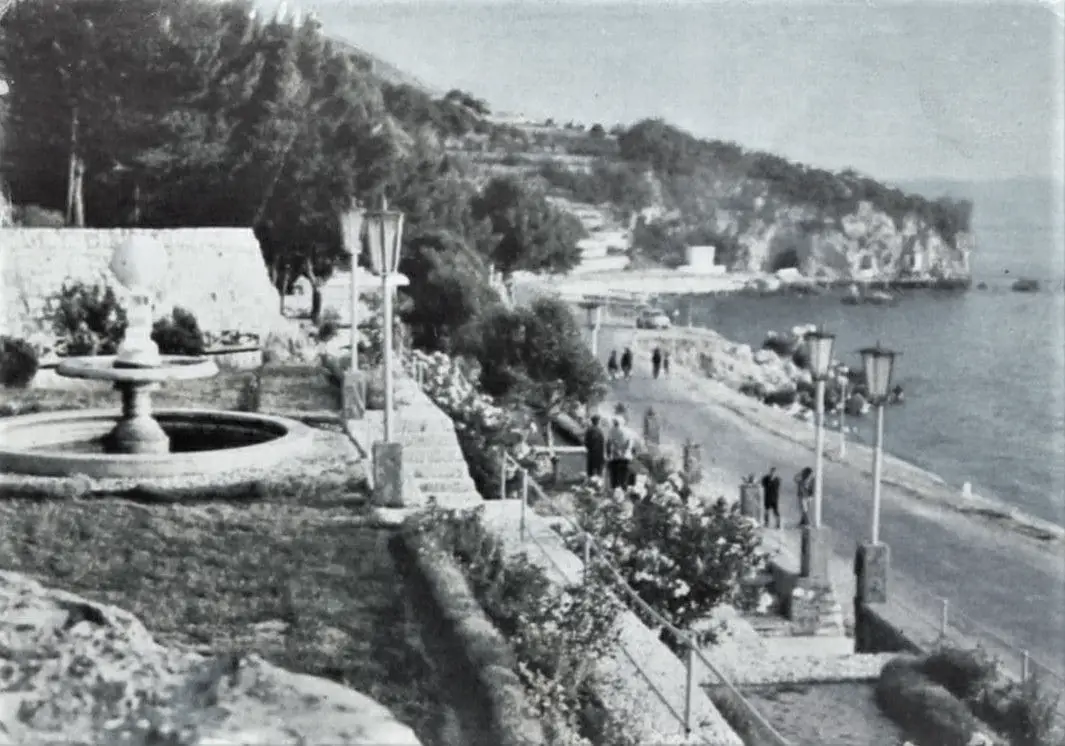

As an old port city, Vlora had frequent contacts with foreigners for centuries. Trade exchanges with all the countries of the Mediterranean basin had been regular and natural. Even the very concept of people on borders, customs and coming and going in different countries, such as in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Malta, Egypt, Tunis, France and elsewhere, was not only an action but also a more than ordinary notion of typical european.

But, starting after World War II and the installation of the communists in power, exchanges with the West were brutally cut off. Regarding the countries of birth, even with them, initially, contacts were almost non-existent. But, after a short period of silence, the first Yugoslav ships arrived at the port, which took more than they brought. Then, the divorce with Tito happened. Again a period of desolation followed. After her, new friends came again…!

Sailors of the Soviet Union arrived at the port. With military and commercial ships. With the names written in Cyrillic letters: “Leningrad”, “November 7”, “Volga”, “Mir”, “Moscow”, “Odesa”, etc. The Port of Skela, the streets and squares of the city, began to be populated by Russians. They had names that many Albanians would later give to their children: Natasha, Ivan, Katjusha, Larisa, Chapajev, Vladimir, Alyosha…!

Russification of the country had begun. Only Soviet films were shown in cinemas. In bookstores, magazines and books from Stalin’s homeland were sold cheaply. Russian songs and pieces were played in the flower garden and dance evenings. Almost every young man or woman corresponded with a boy or girl from the Soviet Union. Those were the years of undying friendship. Then, the unthinkable happened. The big break. Pasha-Limani was emptied. Soviet ships and crews fled. The port of Vlora was deserted again.

In the following years, in Ujin e Tohtë, tankers that came to receive crude oil began to appear here and there. They were Bulgarian, Polish, and East German and, at one time, Panamanian and Maltese ships that worked on behalf of international companies. Yes, unlike their predecessors, their sailors no longer went ashore.

The portal authorities put up a thousand and one obstacles to stop their visits to the city. Then, that rule became clear and categorical. For sailors who wanted to have a drink, buy cigarettes or a souvenir, Albturizmi opened a small bar inside the pier, which Albanians were not allowed to visit.

The port began to be guarded by armed soldiers. High walls were erected around it and barbed wire was placed. Any contact with foreigners was strictly prohibited. For the generations that came, that state of separation and isolation slowly turned into something very normal. Something that did not arouse any kind of surprise. It had been written that they should live apart from the world. Somewhere, in a lost corner of the Balkans, lonely, filliks…!

And, suddenly, after many years, the port came alive again. This time, with ships coming from afar. From far away. With sailors of another race, whom people were seeing for the first time. They came from friendly new countries. From China, Vietnam, Korea, Cuba…! Their ships constantly brought grain and only grain. Almost, in Albania, the lands were dry and turned to stone, and the country was plagued by great hunger.

… Then, from the beginning of the 70s, especially during the summer, buses with foreign tourists started arriving in the city sporadically, making their first stop in front of the “Adriatik” hotel. (During the war, his building had been the residence of Italian pilots. It had miraculously escaped being blown up with explosives by the Germans while they were abandoning the city in October 1944).

Generally, tourist groups came as far as Fier, and then continued towards the cities of Gjirokastra and Saranda, passing through Ballshi and Tepelena. Vlora and the coast of Himara, the most beautiful areas of the riviera, were deleted from the Albturizm map for strategic reasons. First, because the largest military base in Albania was located in Pasha-Liman, so the city had to be as far away from contact with foreigners as possible. And, secondly, because in Porto-Palermo, the Chinese were building another naval base for housing submarines and torpedo boats.

This is the reason why the presence of a tourist group or two or three foreigners for Vlora in those years was an important event. Thus, when a bus with tourists stopped in Flag Square or Ujë te Tohte, that was the event of the day. Within a few hours, in different neighborhoods of the city, people quickly spread the news by word of mouth: “Did you hear…? Some foreigners had come today. We saw them in Flag Square…! To the Independence Monument…! Up in Kuz-Baba…!

…1974”!

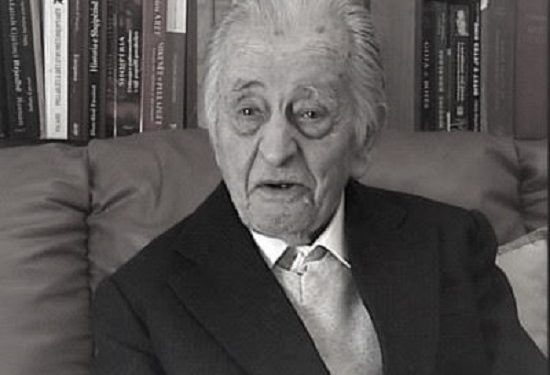

One day in September, as I was climbing the stairs of the “Adriatiku” hotel, from its veranda which served simultaneously as a buffet bar, I heard someone call my name. It was my former professor of ancient Greco-Roman literature, Muzafer Xhaxhiu. A cultured, kind man, with a sensitive and poetic soul, he left the best impressions not only on me, but also on entire generations of students of the Faculty of History and Philology.

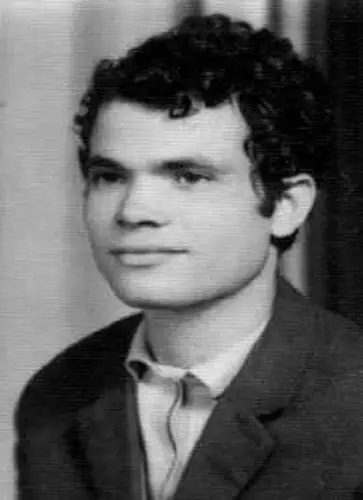

After we hugged, he invited me to sit at the table, there in a corner of the porch where bougainvillea flowers were hanging. But, Professor Xhaxhiu, he was not alone. With him was another person who, at first glance, I thought was a foreigner. Indeed, next to him was a poet from Arbër, invited to visit Albania by the League of Writers. As the professor explained to me, they had almost come from Fieri, because they had not been able to find two separate sleeping rooms in the “Apollonia” hotel.

“Those from the administration of the League have done something stupid – the professor confessed to me in confidence – Instead of booking two rooms, they ordered only one. So I decided to come to Vlora, even though this move is not included in the itinerary and is considered a ‘violation’…”!

Professor Xhaxhiu often accompanied foreigners. Exactly, regarding this fact, in one of his books, the French reporter Jean Bertolino tells:

In most of my travels I was accompanied as a translator by Muzafer Xhaxhiu, a man with a lovely appearance, professor of ancient literature at the University of Tirana. A gentle and sometimes a little timid man, Xhaxhiu is passionate about French literature, which surprisingly he studied in Moscow during the years 1950-1951, when Stalin held the Soviet Union in his iron fist…! During the fascist occupation, M. Xhaxhiu was not a partisan, and afterwards, not evens a member of the Labor Party. So, he is deprived of the honorary titles given to the militants of the National Liberation War. However, Xhaxhiu is well-known, because he is a well-known poet in Albania…”!

After a while the waiter came. All three of us ordered cold lemonade. The waiter, a lively and smiling boy, did not delay and in a few seconds served us on the table, three glasses filled with a thick violet liquid. “This is lemonade”? – asked the surprised poet from Arbër. We laughed. We understood his surprise. In fact, there was just plum juice in the glasses. I got up and went to the counter to ask if they had real lemonade.

“No, we don’t have”! – answered coldly, the bartender. In Vlora, in that season, it was really a miracle to find lemons in the market, especially since its climate was typical Mediterranean. I went back to the table and told them that the bar didn’t have real lemonade, (with lemon juice). The Arbëresh poet did not speak, while Xhaxhiu smiled sadly. We continued the conversation by remembering former faculty friends, many of whom the professor remembered even by name. Then, we talked about literature, Arbëresh authors and some of their books that were also published in Albania.

In the course of the conversation, just as in vain, I glanced around the porch. At one of the tables nearby, I saw the familiar face of a Security operative. I hadn’t noticed him before and, to be honest, his presence made my blood boil. In fact, I knew that whenever foreigners came to the hotel, one of them was present for surveillance. I thought that, under the circumstances, I would do well to leave. Why trouble myself for nothing?

I apologized to the professor using a banal excuse.

– “We will also take a shower and then we will go down to make dinner” – said Professor Xhaxhiu politely. We got up and went together to the hotel counter. Stunted, I looked back out of the corner of my eye. The friend of Sigurimi got up right after us. We greeted each other once more, but without lingering, because the narrow alcove of the reception was full of Chinese people, who were waiting in line, carrying endless suitcases, purses and bags around them. Memorie.al