Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the unknown study of the famous German albanologist, Johann Gerog Von Hahn, which was first published in 1943 by the periodical magazine “Leka”, which was published in Tirana, with the title: “Shqipnija tani one hundred years”. From the numerous researches and studies done for Albania, which date from the second half of the XVIII century and ten decades later, the German author has described in detail the whole economic, geopolitical and trade situation where our country was at that time.

Although it was located in the farthest corner of the Ottoman Empire, and one of its most backward and underdeveloped countries for more than 500 years, for its very geo-political and strategic position where it was located, with the intersection of trade routes , its ports and harbors in the water areas from north to south, numerous mineral resources, handicrafts, orchards, fruit-culture, agriculture, livestock, etc., Albania was and remained a country that was constantly of interest to foreigners. This, among other things, is best seen by a study of the famous German historian and albanologist, Johann Georg Von Hahn, who after many years of research, in his book entitled “Albania now a hundred years “, Has reflected in detail and detail the whole economic-political situation of Albania, since the second half of the XVIII century and ten decades later. From that book, parts of which were first published in 1943 by the periodical magazine “Leka” which was published in Tirana, we have selected some parts that we are publishing below in this article, adapting them to today’s language.

The book of the German albanologist

Johann Gerog Von Hahn

The Pashallëk of Manastir included Central Albania, which at that time was not a suitable political and commercial center. It was divided into seven districts as follows:

Elbasan with the province of upper Shkumbin.

Peqin with the province of Lower Shkumbin.

Kavaja with the coast near Durrës.

Tirana with the province of upper Erzeni and Ishm, a riparian belt up to the mouth of the Drini, according to the legend, up to a man located in the Bazaar of Lezha.

Thus, according to the narrator; de facto Lezha was the same center of Shkodra myderllyk, and the coast that stretched between Mat and Drini depended more on Lezha than on Tirana.

Matja, or the southern wetland of Mati,

Dibra with the Drini i Zi valley.

Gora and Mokra with Pogradec as their capital, on the west shore of Lake Ohrid. All these regions depended on the kajmekami (deputy prefect) of Ohrid, and this on the vali of Manastir, who was also Serasqeri or the Commander-in-Chief of the Turkish army for the whole Balkans. Perhaps someone hearing this work will be surprised to know that the Monastery once had no significance as a city, and as a pasha did not exist at all. And the lands we mentioned above, which were given to the Monastery, belonged to the pashas of Ioannina and Shkodra. For this reason, Mehmet Bushatlliu, in the second half of the XVIII century, conquered the cities and regions of Elbasan, Tirana and Kavaja. But it should be noted that as early as 1836, Serasqeri of Rumelia was settled in Bitola, in order to more easily suppress the Albanian uprisings, and for the same reason was created the pasha of Manastir, which in the beginning included not only the above-mentioned regions, but also the pashalik of Shkodra, Prizren and Peja, extended to Nis. At this time, Shkodra, Prizren and Peja did not have a special civilian ruler.

Trade in Southern Albania

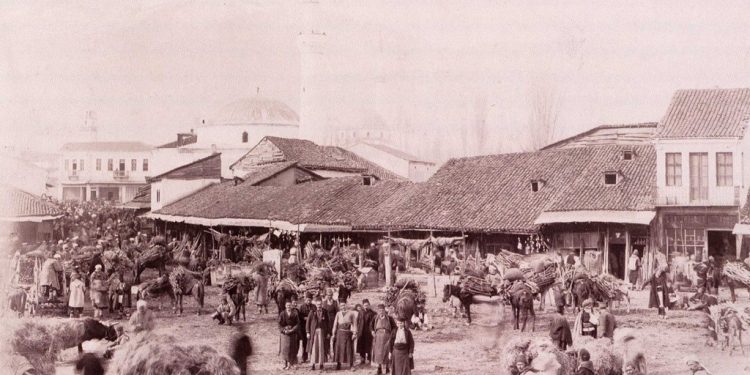

The partition of Albania, as we saw above in this article, was caused not only for political reasons, but also for commercial reasons. And indeed, every pashallak, with its allies, was concentrated in a certain direction in the field of trade, equipped with a route that allowed the passage of goods from East to West and vice versa. Thus, in southern Albania, Ioannina was the commercial center of the country, from where and started the trade route, which from the neck of Zygo, leads to Thessaly. Epirus’ relations with this province have always been very close, so much so that the Turks often put it under a single rule. Central Albania had two trade routes: one connected Vlora with the Monastery, passing through Berat, Korça and Kostur, the other as the famous Via Egnatia of the Romans, connected Durrës with the Monastery of Thessaloniki, passing through Elbasan, Kandavi and Ohrid. The Pashallëk of Skopje was united with Shkodra and the Adriatic Sea via the Kukës-Prizren road, which, passing through the Tetovo Pass, went as far as Edrene. The trade situation of our Albania that 100 years ago deserves a much more detailed study, as it is a very valuable thing to know the economic and social situation of our people, about which until today few have written or spoken. Starting from the south, it should be borne in mind that before Ali Pasha Tepelena, the merchants of this province bought their goods from factories, which then flourished in Turnovo and Ambelaki in Thessaly, and among the markets of Thessaloniki and Istanbul. They also visited the Serez and Përlep fairs in Macedonia, where they received especially the European goods they needed. Maritime trade, as far as possible in those ancient times, was in the hands of the French, who before the Revolution of 1789, with Parga and Preveza, had close and fruitful trade relations. On the contrary, trade with Venice was irrelevant. At the time of the Napoleonic revolutions and wars (1789-1814), maritime trade fell into the hands of Malta, and after the Congress of Vienna, (1815), it fell into the hands of Austria and England. France tried to regain the lost land and repeat the former relations with southern Albania, but failed.

Trade competition of Ioannina with Bitola and Korça

Ioannina was of course the commercial center of the province and the scope of its trade extended beyond the political-administrative border, because it not only sent its goods (fabrics and cosmetics) to Tërballë, and through it to western Thessaly, but made them also Thessaloniki competition in the Larissa market. Ioannina controlled the market of Kostur in Macedonia, because the traders of Kostur, although closer to the Monastery, found trade relations with Ioannina more beneficial than with the Monastery. But later, sometime after 1830, Ioannina found a dangerous opponent in Korça, which managed to emancipate itself from the market of Ioannina and connect directly with Qerfoz and receive English goods through the port of Vlora. This sudden development of Korça has been favored not only by the ingenuity and courage of the people of Korça, but also by the position of that city located at an important crossroads. Ioannina had two piers, the Sajada pier and the Arta pier. The Sajada wharf was not a real harbor, but only a bay where sailors could find protection against the winds of the West. The land route from Sajada to Ioannina was very long (about 20 hours) and very bad, so much so that winter could not pass without a mule or caravan falling in Kalama, the horn of which the road crossed. of trade caravans that did the service Sajada – Janina. For this reason, trade was not very dense and only English fabrics and other lighter goods that Austrian steamers unloaded at Qerfoz passed through this road. Cosmetic goods and heavier goods were unloaded at the Arta wharf, which was much safer. The Artë-Janinë road was also shorter (only 16 hours), and better, so the passage of goods through that road was cheaper. The waters of Preveza Bay, being not very deep (only 12 meters), did not allow large boats to pass and approach the shore, therefore the trade in this area was not large. As a result, that trade was limited to the usual relations at Qerfoz and Saint Maura (where wine was especially bought), and to several other islands of the Ionian Sea. The most famous port of southern Albania was that of Vlora, both in terms of protection of ships against Adriatic winds and storms, as well as trade. Berat itself, since it did not have a safe pier on the coast, used Vlora as its own harbor and took its exports there in small boats. The truth is that there was no other natural scaffolding on the coast, but they were neglected or used only for domestic trade, as they did not constitute an important place from a commercial point of view.

Albanian coast, with 20 customs offices

At that time, on the entire coast of Albania there were about 20 customs offices which controlled all commercial activity that took place by sea. As for imports, the scaffolding of Sajada and Arta were of special importance, as we said above. Parga, on the contrary, after the conquest of Ali Pasha Tepelena, had lost all traces of the former commercial flourishing. Export-import goods were usually held by foreign ships, such as Austrian, English and Greek. Other boats were not seen except in Vlora, mainly when the weather was bad. Southern Albania did not have a merchant fleet, except for a few boats of a merchant from Preveza and Arta, and boats from Himara. From the north, on the contrary, as we will see below, the merchant fleet of Ulcinj flourished. Trade was done especially with Trieste and Qerfoz, being very limited in relations with Livorno, Malta, France and the Ottoman Empire. According to an account that is very close to the truth, after considering the customs revenues of the region, their expenses and smuggling, it seems that the trade movement of southern Albania is now one hundred years old (it is about the period 1843-1943, our note), were at 2 to 5 million gold francs. Of which 2/5 were from exports and 3/5 from imports.

Imports from England, Austria, Russia etc.

Imports from England were these; cosmetics items, fabrics, yarn and other cotton items. It should be borne in mind that at that time many country fabrics were made of cotton and for this reason, the use and trade of cotton yarns was of great importance. Iron, about 8000 kv per year, was used for horseshoes, plows and other thick tools. Their price was 1 grosh (Albanian currency of the time, our note), the first 25 per ok (unit of measure). Raw hides came from Buenos Aires and were used especially for opings. Imports from Austria; iron and iron articles; some 10000 kv per year; fabrics, woolen yarn (some 2000 balls a year, with Vienna labels, cotton things, basma, scarves, etc.), silk things, leather for shoes, paper, majolica, glassware, watches. About 2000 kv of iron were imported from Russia to Albania. From Naples more than 1000 meters of gold wire for caskets and tailors; from Istanbul came some precious silk and woolen fabrics and some embroidered, from Macedonia came woolen threads for rugs and ceilings.

Exports of Southern Albania

Thick and strong shawl and shajak were exported from southern Albania, with which sailors’ capes were once made. They worked in bulk, especially in the Vlach and Pindi villages. So, not only was it enough for the needs of the country, but it was also exported abroad (about 100 burdens a year). In Chameria at that time flourished some burnoti factories that were sold especially among the nearby countries of the Ottoman Empire. As for cereals (corn, wheat, etc.), at that time there was no regular export, as it depended on the harvest and the season. From the oil, among the best years, Preveza extracted about 10000 barrels, Parga 5000, Chameria 6-7000, Vlora 20000. One third of them were exported to Trieste and 2/3 were for the needs of the country. Among the bad years, exports were almost to zero. The olive harvest usually began in November and lasted until spring, as the grains, not ripening at the same time, forced the villagers not to shake them so as not to damage the branches, as was the case in many other provinces. where one year the trees yielded grains, and the next year the broken buds from the shake would grow. Exports began in March. The best oil was that of Parga and that of Chameria, which sold 1 or 2 talers (unit of measurement of that time) per barrel more than the others. Valanidha (Vollonea), about 500,000 liters per year, of which 150,000 from Vlora. Cedars (the best are those of Parga) were exported to Trieste, where they were in high demand by the Jews. In Chameria was planted a special and precious kind of tobacco, coming from Syria, which was called Gjebel. It was sold for 7-8 grosh oka, as opposed to 3-4 grosh for local tobacco. That type of tobacco was exported especially to Qerfoz and Greece. Wool, only from Vlora was exported in June and July about 50,000 oks, especially in Trieste and the price was 10 books (8-9 groshes). The tar from Selenice (which is located 3 hours northeast of Vlora) and the workers who worked there were mainly the Vlachs of the districts, who produced the thick and thin tar that went to Vlora for export. A customs duty was paid, and thick tar (about 300,000 liters) went to Tri Trieste and Venice, and Nap to Naples and from the East, where it was used to paint the body of the vines, which protected them from worms and insects. other harmful. While all the thin tar was sent to Trieste. Lamb and rabbit skin, about 10-15000 pieces from Vlora. Animals for meat, about 10000 heads per year (1/3 from the country, 2/3 from the provinces of Tuna), while the export of sheep and pigs was much smaller. Ushujza, about 1000 oke per year, were once sold only in Parga, some 3000 oke. Turtles, 40,000 pieces per year, 4/5 were exported to Trieste and Fiume. The most important saltworks were located the first half hour from the north of Vlora, the second near the village of Seman and the third near Kavaja. Each consisted of a square sphere, surrounded by another wall and divided into smaller spheres, where through a line the sea water was removed until it reached a height of 6-7 centimeters. In summer the evaporation was so strong and rapid that after 48 hours, the workers with a wooden hoe collected the salt, carefully collecting it in oval piles with a diameter of 5-6 meters and 4-5 meters high. To protect them from the rains, they covered the piles with a thatched roof. In the months of July and August, the Vlora saltworks employed about 100 workers who extracted about 400-500 barrels of salt per day, and per year that amount reached 15-20000 barrels. Most of that salt was sent to Shkodra, through the sailors of Ulcinj, who bought it in Vlora for 10 groshes of horse and sold it in Shkodra for 14 groshes. The rent of the Vlora saltworks was about 150-180000 grosh per year, while the workers’ salary was about 160 grosh per month per person. For this reason, the entrepreneur did not have a large income gain, but usually he was compensated with other more profitable jobs by the government, in order for him to compensate the missing profits or even losses that could come from the activity of saline. During a year in the Vlora saltworks, the inhabitants of the village of Narta usually worked without pay, who for this reason were free from any labor and were not charged with paying taxes or tithes, like the inhabitants of other villages. The production of all saltworks in southern Albania was about 60-70,000 barrels per year and it was used almost entirely for the needs of the country in Albania, and the excess went to other countries of the Ottoman Empire at that time./Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow