By Sandër Lleshi

Second Part

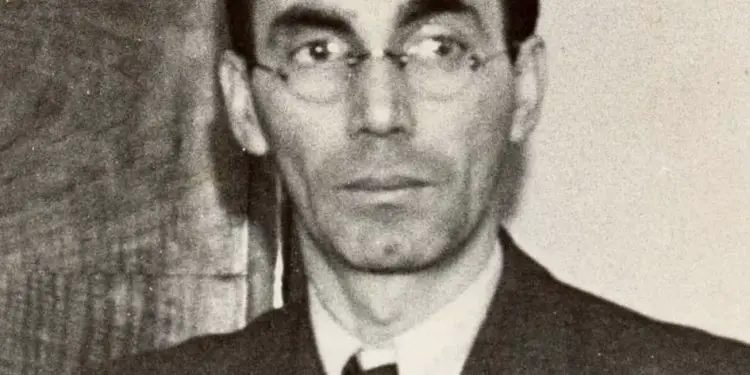

Memorie.al / On the occasion of the birth anniversary of Father Anton Harapi, the renowned history researcher and military officer, Major General Sandër Lleshi, for the first time presents to the public a collection of facts shedding light on the political engagement of Father Anton Harapi in the Regency Council. As a reaction to the famous prayer for Albania by Pope John Paul II, a notice from the Albanian Telegraphic Agency, dated 10.10.1980, at 09.55, transmitted in English, states: “In Albania, religion has lost the battle in the ideological and spiritual field once and for all. For this reason, crocodile tears were met in a completely different way than the monarch of the Vatican had hoped. If the Popes of Rome continue to defend a clergyman condemned by the court of our people because he was an agent or collaborator of the fascist and Nazi invaders, we would say that this further discredits them. …! Father Anton Harapi and others like him, following the example of Pope Pius XII, who gave his blessing to the Duce and Hitler, put themselves at the service of the foreign invaders, and they cannot be distinguished from all the collaborators of the invaders in Albania.”

Continued from the previous issue

INVOLVEMENT IN POLITICAL LIFE

Father Anton Harapi’s decision to become politically involved in the Regency Council in 1944, after approval from the Catholic Church authorities, ‘seems to have been one of the most difficult decisions of his life. Overall, the political and military situation in Albania was very complicated. The capitulation of Italy and the state vacuum created afterward, the considerable number of Italian troops remaining in Albania without a unified command, the interests of the Allied armies in gaining control of the areas occupied by Italy, as well as German interests in preventing the entry of Allied troops into the Balkans, characterized the general picture. Added to this was the presence of an increasingly growing partisan movement, along with the danger of internal anarchy and civil war. Neubacher also describes the complexity of this situation in a telegram dated 12.09.1944, to the German Reich’s Foreign Ministry, where he writes, among other things: “The events of recent months and the intensive English propaganda in Old Albania (today’s Albania, without Kosovo, S.LL.’s note), especially in the capital among the majority of the population, have created the conviction of our defeat. Our initiative for the creation of an independent Albania was met with formal, and even juridical, skepticism. It was clear that these men, above all, were worried that by approaching Germany, now on the eve of the Allies’ victory, they would risk their safety and property, as well as the country’s interests. For this reason, we have taken steps to create a national committee, with a composition different from what we initially thought.”

Precisely at such a time and in such a situation, Father Anton Harapi makes a decision that is outside the normal trend of the time, that is, sublime. He accepts an official position as a member of the Regency Council at a time of complete turmoil and in a country on the brink of an abyss. How is this possible?

It seems he had a premonition of his fate, and in his speech to Parliament, upon his swearing-in for the post of member of the High Regency Council, he gives an answer to all those “smart people” who understood the danger of the situation, but also, it seems, the answer to the future communist judges, when he declared: “I was compelled to choose one of two things: either to do a foolish thing by accepting this office, or to show a weakness by stepping away. I decided it was better to do a foolish thing: or – as those Albanians who want to keep themselves clean say – I wanted to compromise myself.”

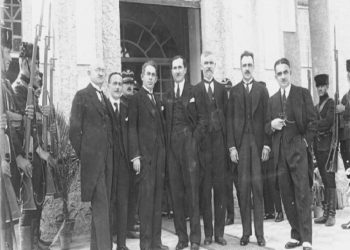

Like many moments in Albania’s history, its occupation by Germany needs to be studied in a complex manner so that historical facts are reflected stripped of ideological comments. At least one thing is clear: The study of numerous German documents of the time regarding this issue highlights the political effort to consider the case of Albania somewhat differently from many other occupied countries, for reasons briefly discussed at the beginning of this scholarly and analytical article. Within the framework of this specific political treatment, by Hitler’s order dated 03.10.1943, the post of “German Plenipotentiary General in Albania” was created. The stipulations for the implementation of this order on the same date stated: “The German Reich has recognized the newly created National Committee as the government of the independent and friendly state of Albania. By order of the Führer, the post of ‘German Plenipotentiary General in Albania’ is created to represent the German Wehrmacht to the Albanian Government. Consequently, the creation of a German military administration in the territory of the Albanian State is not foreseen.”

Against this general political, military, and social background of Albania, it is somewhat simpler for anyone to understand the motives of Father Anton Harapi’s decision to engage in the highest structure of the Albanian State. Neubacher’s book clarifies that the political scene of that time was characterized by the antagonism: Mithat Frashëri – Xhaferr Deva, or as Neubacher says: “Old Albania – New Albania,” leaving no specific room for an active executive role for Father Anton Harapi. Essentially, in the book, it seems as if the person of Father Anton Harapi primarily served Hermann Neubacher to personify his sympathy for the high virtues of the Albanian people. Neubacher dedicated the chapter on Albania from his book on the Balkans to Father Harapi:

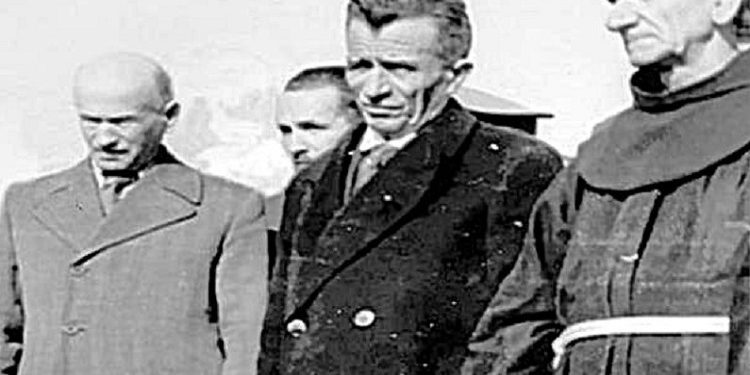

“The same fugitive told me about the end of Father Anton Harapi. But I must add something beforehand to his story. When our withdrawal from Albania began, I asked Father Anton to leave the country immediately and offered him my plane for this purpose. He thanked me and sent word that God had appointed his place, and if it was God’s will, he would have to die where his priestly duty called him. The man from Durrës told me that his friends were keeping him hidden. The communists, who were searching for him everywhere, entered the house that sheltered him. They did not find him. As they were leaving the house, they saw a dental prosthesis in a glass and demanded to know whose it belonged to! When they started to mistreat the people of the house, who were trying to get out of the situation, Father Harapi came out from where he was hiding and surrendered to the government’s ‘hunters’. The man who entrusted this story to me told me that he went to the gallows with serene composure. Father Anton Harapi hailed from Northern Albania; he received his secondary education at the Franciscan schools in Merano and Hall in Tyrol. In Rome, he studied theology. Before his end, he saw the places of his early youth one more time. His departure from Tirana at that time is unforgettable!”

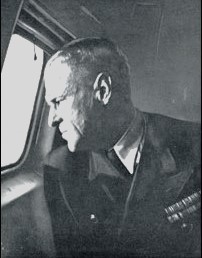

Furthermore, Neubacher closes his chapter on Albania with this episode: “It was the end of June 1944 when, fed up with the government crisis, I left Tirana. Due to the proximity of English fighters on the other side of the Strait of Otranto, I could only travel in the dark. The plane had started moving on the runway with lights when the crew managed to stop the vehicle with shouts. – ‘What is it, who is there?’ ‘Father Harapi!’ And the small Franciscan climbed into the belly of the plane and stood smiling in the small passenger cabin. ‘I can’t stand politics anymore! I will fly with you!’ The Heinkel took off; twisting above valleys and mountain ranges, hovering over the wilderness on whose rocks the first red glimmer of the rising sun had begun to shine. Father Anton, who was seated opposite me wrapped in his habit, took out his prayer book from a bloated bag, which was his only luggage, and began to pray. For several days, he was my friend in Belgrade. I still see before me the small ascetic creature, with a face brown as if carved in wood, from which a jolly and large nose protruded, holding the prayer book and wandering up and down amidst the splendor of the flowers in my garden. Later, Father Anton traveled to Vienna and then to Tyrol. After a few weeks, he returned to Albania, where death awaited him. No revolution can extinguish the memory of such a man. May the eternal light he served illuminate him?”

And this is certainly what would happen. At a time when many state authorities, political representatives, economy, and culture sought every possible alternative to leave Albania, which was acutely threatened by the danger of communism, Father Anton Harapi, despite everything, acted differently, contrary to the general trend of the smart people, contrary to reasonable advice, without calculating for his safety. He returned to his Homeland, where in 1946, he was awaited by the sentence of those whom he had forgiven in 1943 and whom he would forgive even today if he were alive./ Memorie.al