From Dom Zef Simoni

Part seventeen

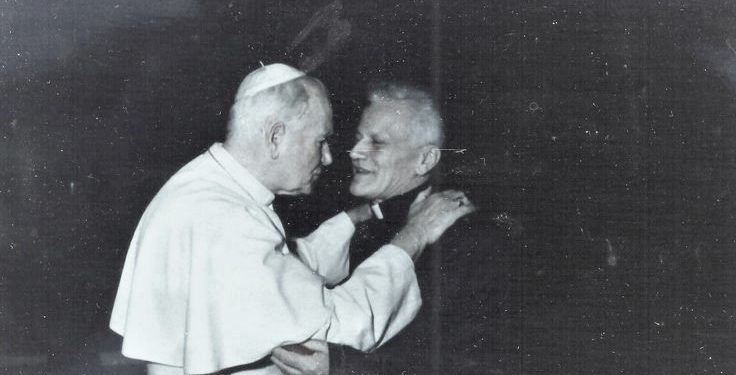

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990,” in which the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study begins with the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to detach the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply rejected Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

Now, something extraordinary shortly after midnight. A search at home. Do they really go to seize a person at this hour? A military incident? Some major discovery? Pure madness! After the doorbell was heard several times, the house door was opened in sorrow by my brother and sister, awakened from a deep and fearful sleep. They rushed through the rooms and, for nearly four hours, conducted a meticulous search. The operative who had spoken to me, another Sigurimi official, the police, and the chairman of the neighborhood People’s Council had all come to the house.

They found several religious books. A discovery! Terrible for them. They find religious books, a holy card. A religious atom. Atomic-biblical energy. A blast. An explosion. “Quick, the record of proceedings!” These things cause allergies in communists; holy cards suffocate them. They caught the enemy in his guilt. They have him in a room with bars, without glass. When the officer returned from the house to the room where I was held, he called me a “liar” with his mouth full of spite and struck me with a fist to the head and with the tip of a Chinese umbrella in the stomach. Once again, I suffered because of China, even after the fallout.

The officer neither knows nor wants to know about mental restriction. I, moreover, have a duty to defend the truth against democratic deception or a democracy built on lies. I forgive you, oh hitting man, oh raging devil. I forgive the guilty. I do not sleep. I pace the room. Early during the day, officers and officials who were starting their shifts came to see me. “This one,” they said of me, “was caught performing Masses, in religious services.” “He is a strange man,” they said of me. Someone else said these words: “They’ve caught the kaurr (infidel)!” It is an old-Ottoman notion. This word was said after nearly 77 years in the independent Albanian land, across its 28,000 square kilometers. “I am a kaurr! My name is Zef. Dom Zef.” Shortly after 7:00 AM, when the officials arrived at their offices, the vice-chairman of the Department came. “Is your name Dom Zef?” he said. “Yes,” I replied. Together with him, after a few minutes, the chairman of the Department himself arrived. To tell the truth, in my presence, both behaved well. The storm had begun to subside. “Why do you perform religious services?” the chairman asked. “Convictions are not forbidden, but the service is forbidden by law, by the constitution.” I told them: “I was not caught performing a service; I was caught eating bread.” In my mind, I thought, “I was caught at an Albanian table. They have betrayed the host’s bread. Albanian against Albanian.”

The Sigurimi Operative Named “Kongres”

After these meetings, they began to behave well. The local operative who had arrested me, named Kongres, came to see me. “I am serious,” he said. “We also know how to speak like human beings. Are you hungry? Do you need anything? Do you have money? I will buy you something to eat.” “Thank you,” I said. “I am not hungry.” A policeman soon brought me a plate of well-prepared beans and bread. He gave it to me with great politeness. Among the policemen, there were those who behaved with a sort of friendship. Perhaps they were believers. There were indeed those among them who were religious. They liked my stance. After lunch, around 5:00 PM, they took me to a room, the office of the chief of investigations – their heavy offices. The books they had taken from me that pitch-black night were to be registered in my presence. They strictly forbade me from touching any book or anything else with my hand, under the threat of the clubs that three or four officers had with them.

Here, a miracle. I see the Pyx (Teken). “Are the Eucharistic Hosts in there?” “Yes.” I found Christ in the room of violence. I remember Christ before Annas and Caiaphas. Christ under interrogation. Miraculously, the officer, Llazari, who had struck me with his fist that night, did not say a word when he saw me taking the Pyx with the eight consecrated Hosts. I consumed them. Seeing that I was wiping it with my finger with the gesture of a hungry man, he continued to remain silent. And after I licked it and wiped it with my handkerchief, he let me eat the unconsecrated hosts that were there as well. While he would not let me touch any book or paper without his knowledge, he let me live Christ, or rather, Christ live Himself.

Surely this stealthy and predatory officer would not leave me for several months. They left me in that room for nearly two hours. Conversation. I opposed them. They closed it with a statement from me, which I signed: “I hold my religious views; I am against materialism; I do not agree with the party’s decision to close the churches; and whoever asks for a religious service from me, I will perform it, all of this because they asked it of me.” A declaration that he was a believer would also be made by Ndreca Hanxhari, the master of the house who was there in another room. Around 7:00 PM, they released me. “Now you have no business with us. You will have business with the people. They will decide for you.”

My Denunciation at the Front Leadership in the Neighborhood

One Monday, it was the day of Our Lady of Shkodra. The Front Council notified me to be at a meeting at 6:00 PM. This meeting was held because of me. About one hundred and fifty people were called to this meeting. There are policemen inside the hall. Policemen outside the hall. There are cadres from the Sigurimi and the Front, conservatives of the regime, war veterans sporting proud mustaches and Republican hats that do not suit them – pensioners who move from cafe to cafe like flies in the square built for them because they brought the “New Albania,” the “Red Albania.” They were assassins during the war and fought with passion, with fanaticism, with fundamentalism for freedom of speech and the press – allegedly regardless of religion, region, or idea – only to later destroy churches and mosques, while they themselves enjoyed all material benefits, meaning privileges and articles of abundance, because they deserve them as the workers of the order of violence. Boasting. These are “the people.”

They brought me close to the presidium to be seen more clearly. Very fierce attacks began, telling me: “You have come out of prison remaining an incorrigible person; you continue to perform religious services; you seek the opening of churches.” A loud and prolonged “uuuu” was the response from those beasts in the hall, with piercing screams similar to those of crazed sports fans in a stadium. One person spoke about Albania’s backwardness before the liberation, blaming the Catholic Clergy. Another – and this one was a Catholic, may God forgive him – lashed out against Christ. And so it went, speaking of the material interests of priests, claiming they serve while having jars full of butter. To all of it, I replied calmly. And finally, they told me that I was with the Vatican. This meeting closed with my words: that as a Catholic and as a priest, I was with the Holy See. The meeting ended after three hours with the words that the Holy Spirit put into my mouth, and they left with the thought that I was indeed incorrigible for them.

Llazari, the Sigurimi Officer

After a few days – this being a day after a meeting of the District Party Plenum where Foto Çami had participated – that Sigurimi officer, Llazari, came to my house. This time, he came sent in the name of the Party Committee. He notified me that “the state will take an interest in your health, so declare what you needs have.” I thanked him but told him that I needed nothing. He continued, and this entire conversation took place at my garden gate. Finally, he told me: “You are free to go anywhere, to any village, but be careful not to carry a service kit with you.” He spoke these last words in a way that seemed unimportant. “Be a patriot,” he told me. He seemed to take a kind of satisfaction when I affirmed: “I have been and am a patriot.” I then remembered my words in court years ago, when I told them: “I am a patriotic Priest.”

Stalin in great danger!

The Fall of Empires and the Third Arrest

How would it look for communism, as a system, to come to an end? Are there hopes and are there predictions? It is a matter of the collapse of a camp, and who would have thought that this camp would burn like a shack, like a piece of straw. Mao Zedong’s ideas and Eurocommunism had no strength; in their likeness, the countries that had tried that kind of life – that unnatural dictatorship and order – had entered the path of bankruptcy, which means the end. End, end, end. It seemed entirely unexpected, but the causes had turned this organism into something that no longer had even the power of an organization. The sky of Eastern Europe wanted to clear up, and while a suitable Gorbachev worked in his own country with Perestroika for new days, the satellite states moved far ahead. Solidarność with the Pole Lech Wałęsa – a brother to Wojtyła – after some blood was shed on that soil, gave heart to its sisters for the sanctity of victory and civilization.

November. December. Stop. The end of the year. The end of bondage. Stop. The freedom of Warsaw is followed by Budapest. The year 1956, once a marked year, now links to these final days. One “eye” of Germany, gravely ill, began to heal. As soon as the infamous Berlin Wall collapsed, she had both “eyes” in her forehead. This happened on November 9, 1989. Prague was resurrected. Zhivkov falls, and Bulgaria straightens its neck and its frozen head. Romania sheds blood – some 28 days that shook the world – and the world was stunned as Ceaușescu and Elena, just days after their magnificent victory at the congress, fell into the hands of justice. A great stake and this one bore no blood on the day of peace: “Glory to God in the Highest and peace to men of goodwill on earth,” on December 25th. Stalin, who had died for himself on March 5, 1953, died for others toward the end of this year, this December, amidst these events that would erase memories, solemn meetings, works, and busts in halls and squares. Carrying the broken busts in wheelbarrows, people mocked and struck the heads and faces of the “International Papa.”

Could Albania remain the only Stalinist country? For what reason, for example? Do not say that word! Albania is very bright, but inside there is pressure. It is very difficult. In this land of terror, a word, a gesture, a “V” sign with two fingers – the greeting of youth in the streets for democracy – is very precious. A proud stance of more than three thousand young people who had taken their place before Stalin’s bust, in the main square and streets of the city of Shkodra, ready to topple it. The living wants to bury a stinking dead man. People talk about the 11th and 14th of January in the city, before the bust. The youth made noise and, standing close to one another, let out collective shouts – “ou, ou” – before the Post-Telegraph building. The square and the streets on all sides are full. The police are on the periphery, but they stay quiet. Come and don’t stay. They are afraid. Who isn’t afraid? Force is visible. It is a silent demonstration. The numerous police and the Sambists (Special Forces) of the Sigurimi stay in silence.

With great tact, their cars called “Garancia” and masked ambulances with photo-cameras inside pass by, quickly seizing one, two, three people. These are moments. Nothing more than a gathering, courage, irony, laughter, enthusiasm, tension, and the anticipation of what is happening. The sunny day of icy cold ends with comments, with insults toward the dead Enver and the living Nexhmije. Rumors have spread that in this event, there are priests who direct a spiritual connection with the Romanian priest who gave the signal in Timișoara. That evening, they made several arrests. The next day, they called several people to the Shkodra Department. Called and released. Released and called.

The Third Arrest: Dom Simon Jubani (January 16, 1990)

The Ministry of Internal Affairs is very busy. Arrests are being made from Tirana. At 5:00 PM on January 16th, the usual State Security officer, Llazari, came to our house. He had also come on the 9th. Was this connected to the events of the demonstration – their plan? He had looked for my brother, Gjergj, under the pretext of knowing the family’s income. Do we link this action to the words of three months ago, that “we will do you good”? With a forced gentleness, the Security officer told my sister, who had come out to open the garden gate, that “we are looking for Zef, for the People’s Council.” I go out. He takes me with him. At the turn of the road, he meets this man and another officer. Both in civilian clothes. We head not toward the Council entrance, but toward the Department of Internal Affairs.

Upon entering, the officers, raising their heads slightly, sternly announce my arrest. The two of them take me by the arms and, crossing the courtyard of the Department – where perhaps more than a hundred high-ranking officers were found, dressed in fine civilian clothes, elegant coats, some with glasses whose frames shimmered with gold in that heavy twilight – something between gloom and anxiety was felt. Groups standing around were busy with one another, performing quick actions to make everything as tragic as possible. I am in a room, an office, among seven or eight investigators, two of whom held black rubber clubs. They accused me of dividing Catholics and Muslims. I do not understand this accusation. “I do not do such a thing,” I told them. Later, I would understand their statement, as almost all Catholic elements had been arrested in this movement.

They wanted me to declare my views, which I had done three months prior. They pulled my statement from the file. They asked me to write it in script, as they wanted to know if it was I who had prepared the tracts distributed that day. They wanted to recognize my handwriting. They quickly sat me down, and as we went down the stairs with our faces toward the wall, I found other prisoners. I heard voices, including the voice of Dom Simon Jubani. It was a state of panic, and the darkness that was now falling spread heavily over the city, covering our sorrowful homes and families. This, too, could be one of the terrifying nights of my life. A night of contrasts and fury. They put us into designated cars, bound between two Sambists. Every car had two prisoners and four Sambists. The journey was to Tirana. More than ten cars in a single column. Security cadres awaited us at the central investigation unit in Tirana with smiles and their ironies. The police seized us and took us straight to the isolation cells. You have no time to think, to feel sentimentality.

Strange! At 5:00 PM, I was at home by the fire, struggling with a flu I had endured on my feet, and now, before 9:00 PM, I am in isolation cell number 28 – a room with two flasks, a window and door with bars that clank loudly when opened or closed, and a swift policeman who takes me in and out of the room several times. A state of fear, of terror. The investigation begins: twice during the night. I am accused under an arrest warrant of having participated “with a group, for the violent overthrow of the people’s power.” I do not accept it and I do not sign. A bit of capriciousness has come over me. They want to know my movements on January 11th and 14th. Four or five investigators insist on this. They are not calm. They stay on their feet. They ask questions rapidly. They tell me that “not only were you aware of these events, but you were one of its organizers.” “I know nothing of this matter,” I told them. I refuse by all means. “You are filmed on video-tape on the 14th,” they told me insistently. “It is not true,” I told them. “Because of the flu, I stayed home.” They continue the questions: “What were your connections with the movement, with the revolt?” “No connection,” I told them. “I am against revolts. Christianity does not want blood. A Christian dies for himself.” Thoughts came to me. “Why do these things happen?” I wondered, as frantic actions were carried out by them; doors could be heard opening and closing constantly and furiously throughout the night. Voices and tortures were heard. To them, I was a person who had become very visible for religious activity and had contact with the youth. But they surely knew that in those days I had been home, that I was not involved in this event. Therefore, I am arrested for nothing. Always for nothing. But the truth was that I found myself in the heavy isolation cell. What was happening in these stormy, shocking hours? These people are dangerous and go madly rabid when they have no time, when they are cornered. The dictatorship becomes very sharp.

The Chief of Investigations, Qemal Lame

The twenty-four hours of the Postriba Movement flash through my mind. And the morning of that September in 1946, before the leaves had begun to fall and nature’s storms had started at the beginning of autumn. A heavy sky and strained politics saw the first contingent laid on the ground under that terror and with a Serbian pincer. After lunch, at two o’clock, the doors opened strictly, and bound tightly with irons on my hands, they took me to another room. Tired from the situation but calm within myself, I find myself before four investigators. In the middle is the chief of investigations of the Republic, Qemal Lame. After my hands were unbound: “Please (Urdhno),” the chief told me, to sit in the prisoner’s chair. “What is this?!” I thought to myself; they never say the word “please” to a defendant. They had told me during the meetings that “the Catholic Clergy is anti-national.”

I told them, throwing it back at them with their own arguments, which they had affirmed for forty-five years: “You have pointed out more than forty Catholic priests as exponents of patriotism and culture, starting from Gjon Buzuku to Dom Ndoc Nikaj.” The honored men of a nation slept in history and were praised in the press and news, while their lives and biographies were being deformed, and their future brothers experienced massacre and martyr deaths. And if those who died had been alive?! The chief of investigations dealt with me with a calm, measured behavior. A dialogue. He told me that “the Catholic Clergy has always been against the policies of Montenegro and Serbia.” “Yes,” I replied. “Can you prove it to us?” I decided to speak freely. I gave several proofs and arrived at the “Highland Lute”. I now felt no flu, no hunger, no fatigue.

“Fishta is a patriot and a man of letters,” I told them. With a sliding respect and wisdom for him, he replied: “Fishta is a patriot and a great man of letters.” It was like a resurrection in this room, which was beginning to seem literary, religious, diplomatic, historical, political; and it seemed to me that Fishta was emerging majestically from the shadow of the Assembly, and the poet of the nation greeted the unforgettable mountain peaks, the “wide fields and green hills,” and entered everywhere – even into this martial room, even into his famous and precise verse: “After today, I am not Albanian.” Why should I not offer a critique of the intentionally wrongful interpretation of this patriotic verse of his? For this verse was linked to the future, because the Fatherland, according to Fishta, was and would continue to be in the hands of adventurers, deceivers, liars, thieves, and criminals. Ideas came to me with clarity, and words were expressed with a certain cadence. I was at war. Here was a culminating point. Fishta had immortality, but they had not let it be seen.

It is an appearance now in this room. Through these rooms – square, dry, smelling of blood, smoke, and military poison – those who had spoken well of Fishta (and well would be spoken of him) would set out on a long road of suffering. But it turns out there are not only moments, but also periods when the strong, the great, grow even stronger in calmness, in rest, in silence, and the lines of his every word are analyzed more deeply, to give greater victory to the great poet of the nation, for a nation broken once in retreat. It seemed to me that everyone saw – even those who had persecuted him saw – how his great head was being exposed once and for all; his genius, that broad forehead, that shadow as heavy as the mountains – of those mountains, sorrowful for many years; they saw his habit and his cord. “A light burden,” and those eyes – perhaps the only eyes that have surely led the time./Memorie.al