By Raimonda MOISIU

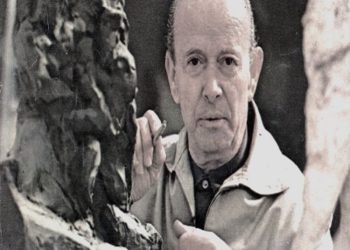

– This rare interview with Dr. Harold Hayes comes for the first time to the Albanian press, conducted in 2015, when he was still alive and at the age of 92. By profession, a military doctor, Doctor of Science, Harold Hayes closed his eyes forever on January 29, 2017 at the age of 94. –

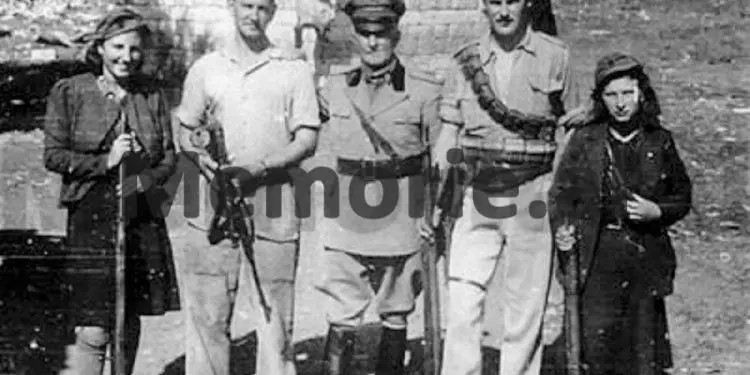

Memorie.al / Dr. Harold Hayes was the last surviving member of a team of American doctors and nurses, who were on a medical evacuation plane in November 1943, which was forced to land in a harsh and dangerous mountainous terrain and unknown to them, (600 miles – hundreds of km.) along the Adriatic coast, during World War II, in Albania occupied by Nazi Germany. The group of 30 people, including 13 female nurses and 13 male doctors, along with the four-person crew of the plane, were suddenly stranded for nine weeks, hiding in the caves and snowy mountains in the villages around Belsh, Albania, very close to the rear of the German military troops on the war front.

The survivors faced hunger, hopelessness, often from the bombings and attacks of the German Nazis, snowstorms and the terrifying agony of life or death. But also affected by lice and physically weakened by diseases, such as dysentery and their negative consequences, but in the end they manage to escape and survive thanks to the help, humanity, courage and heroism of the Albanian people of the Belsh and Berat area. The heroic odyssey of those Albanian partisans and villagers who helped, sheltered, and fed them was classified as “Top Secret.”

The survivors were advised by their military superiors to keep this story a secret for years to come, not to discuss the details of this event with anyone, not even their family members. Keeping this humanitarian event secret, not only during the War, but also years and decades later, was to protect the people – the Albanian partisans and villagers of the Belsh and Berat areas, who helped the group of American nurses and doctors along with the aviators’ means of escape, with unparalleled heroism, generosity, courage, and bravery.

Some of the Albanian partisans and villagers were shot by the Nazi Germans for their acts of humanity, while others after the war, based on rumors spread under their breath, suspected of having helped the Americans, were executed by the communist regime in Albania, and led by Enver Hoxha. Almost 70 years later, Dr. Harold Hayes, the only surviving member of the group, then only 21 years old, now 92 years old, tells us this rare story and his experiences in this event.

Mr. Hayes, what was your role in the US Army Air Forces and where were you serving in early November 1943?

My role was that of a military doctor and I was part of the 807th Air Medical Evacuation Squadron, stationed in Catania, Sicily. Our squadron departed from Sicily, (southern Italy), with transport planes carrying medical equipment and staff to the front lines, and we helped evacuate the war wounded, escorting them on planes to our bases in Sicily or North Africa, to receive better medical treatment.

Who was traveling with you in the C-53D transport plane that November day in 1943?

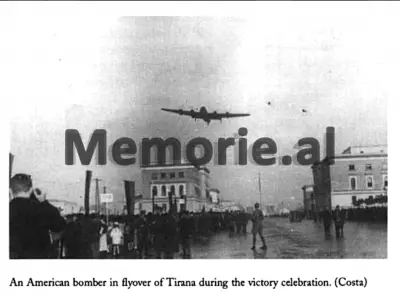

This dangerous adventure began two months after Benito Mussolini’s Italy capitulated, and Allied forces were also positioned in Italy, to launch the final assault against the Germans across Europe. On November 8, 1943, a plane from the 807th Air Medical Evacuation Squadron of the United States Army Air Forces took off from Catania, Sicily, bound for Bari, on the east coast of Italy, where hundreds of wounded soldiers were awaiting air evacuation.

There were a total of 30 of us on the plane; the two pilots, a radio operator, and a crew chief, plus 13 female nurses and 13 male doctors. The rain that had begun to fall three days earlier did not deter any of us from undertaking this secret mission, to leave Catania. So our squadron commander decided to send half of the medical staff to help evacuate the many wounded waiting. Only one member was not part of the squadron and the crew of Flight 807, he was a doctor from Squadron 802, who came with us to Bari, in southern Italy.

-What happened and why were the pilots forced to land the plane?

The evacuation plane was powered by two engines and carried no weapons, because the lead pilot, Charles Thrasher, 22, did not anticipate any combat. The 13 female nurses were lieutenants, and were between the ages of 22 and 32. The 13 male doctors, on the other hand, were the equivalent of sergeants, as were the aircrew, and ranged in age from 21 to 36. When we took off from the Sicilian air base, there were no clouds in the sky, but the closer we got to Bari, the more they appeared. An hour into the flight, the plane was caught in a snowstorm with strong winds. We initially lost contact with the base in Bari.

The pilots climbed the plane above the clouds, but when they climbed to about 8,000 feet (almost 2,500 meters above sea level), the wings of the plane began to ice up, so the pilots were forced to enter the clouds, from where they could see a coastline; the pilots thought they might be flying along the west coast of Italy, but they did not realize that they were flying along the Adriatic Sea. The pilots tried to land on what looked like an abandoned airport, but as they approached, someone started shooting at the plane and the pilots were forced to immediately take off and back into the clouds. This was perhaps the most terrifying part of the flight, through a valley where the mountain peaks were higher than the clouds.

When we emerged from the clouds, the plane was very close to a German fighter plane and then another. The pilots continued to try to avoid the enemy planes, until the plane plunged into a heavy storm over the Adriatic Sea, the compass and radio communication failing and not working. 100 miles off course, the plane passed the coast of Albania and was spotted by German soldiers, who began firing at it with anti-aircraft guns. So the plane went 25 miles inland through a swamp. Willis Muchay, 23, the crew commander, was the only casualty, with a knee injury that left him unable to walk.

Who helped you after the crash?

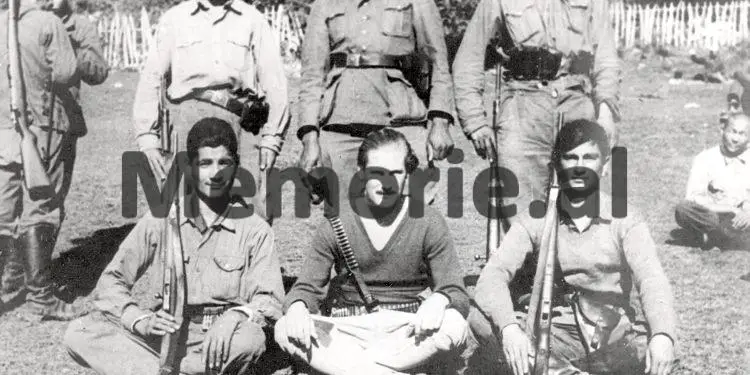

All 30 members of the American squadron were scared and confused, and we had no idea where we were. Fearing a fuel explosion, we immediately got out of the plane and suddenly came across a group of rough-looking men with rifles on their shoulders and knives in their belts. They were Albanian partisans, members of the resistance groups (National Liberation War) who were fighting against the Germans. One of them spoke a little English. His name was Hasan Gina, who had become a partisan and was fighting against the German invaders. He was also the commander of the partisan detachment.

He told the Americans that they were in Albania, 150 miles east of Bar, on the wrong side of the Adriatic, surrounded by German forces who had occupied Albania for months and were also in the midst of a civil war between rival groups; the Ballistas and the Partisans. The Americans knew almost nothing about Albania, a small, mostly Muslim country that had changed little in centuries. The mountainous terrain was extremely rugged, ringed by poor villages. There were no railroads and few roads. Mules and horses were the main means of transport.

There was little running water or electricity. The winter was harsh, food was scarce, but they and some Albanian villagers from the Belsh area helped us immensely. Over the next few weeks, guided by the Partisans, we climbed the mountains and walked stealthily along the valleys, sometimes even sitting down to rest. Sometimes we walked all together, but there were times when we split up into small groups to avoid German patrols, stayed out in the open, or took shelter in the houses of the villages we passed, sharing cornbread with the villagers.

What was your biggest worry when you were trapped behind enemy lines?

One of our biggest worries was that the American army, as well as our families, did not know where we were. They did not even know we were in Albania; they knew nothing about our fate and our lives. Another major worry was that our shoes were quickly wearing out, due to the mountainous terrain, especially those of the nurses. We hoped to reach the seashore as soon as possible, and the only way was to walk as much as possible. All 30 of us were classified as “missing in action” and the authorities sent telegrams of condolence to our families. Meanwhile, the survivors carried the wounded sergeant, who could not walk, on a stretcher made from airplane seats, until later the Albanian villagers brought a mule and we put him there.

After five days through the mountains and the houses of the villagers, we reached a town controlled by the Partisans called Berat, where we were cheered by the locals who thought we were members of some Allied mission to liberate Albania. There we also met other Partisan leaders, and learned of a British agent who had recently parachuted into the country. There we stayed three days, and on the fourth day we were awakened by gunfire and the explosion of artillery shells as German forces entered the city. In the confusion that followed, German planes hit a truck carrying some of the fleeing Americans. Three nurses separated from the main group and stayed in Berat; they took shelter in a farmhouse and hid in the area for four months.

How did the group fare during those difficult months?

For the most part, we got along very well, but there were a few of them who were mistakenly scolding each other. When you are hungry, cold and tired, you forget almost everything else and think only of survival. Watson, one of the nurses, said: “Anything a doctor can do, I can do,” and that is exactly what she did. On November 27, 1943, British intelligence in Albania learned from partisans that American plane 807 had been shot down and that the nurses, doctors and crew were alive, trying to reach the seashore. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of Allied Forces in Europe, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself, broke the good news to the families of the missing.

In December of that same year (1943), another American rescue plan was launched, led by an Army captain, Lloyd G. Smith, 24, who was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. Under cover of darkness, he slipped by boat to the heavily guarded Albanian coast and set up base camp in a cave in the cliffs overlooking the Adriatic. Others joined him, and they moved inland to find us Americans. Meanwhile, the British organized a second rescue effort, led by Lieutenant Gavan Duffy, a secret agent who had arrived in Albania with a small team months earlier by parachute and on foot. Through partisan contacts, he found the Americans in eastern Albania and began leading us westward, aiming to reach the coast.

But halfway, at Gjirokastra, German troops blocked the road and we were too tired, sick and exhausted to continue. He radioed for an American air rescue. Two C-47 cargo planes flew in with fighter escorts, but the Germans spotted them and Lieutenant Duffy aborted the plane’s landing. But we resumed our journey and with American and British help, we reached the coast. On January 9, after a 63-day ordeal, the 27 Americans – 10 nurses and 17 doctors and the flight crew – boarded a British ship and crossed to Italy. Three nurses were left behind in German-occupied Berat. Captain Lloyd Smith brought them safely in March 1944. Riding mules that we rode in a pack for most of the way, we reached the coast and were met by a torpedo boat that took us across the Adriatic.

Why were you forbidden to tell anyone about your experience in Albania, even after the war was over?

When we returned to Allied bases, our military superiors did not allow us to tell anyone where we had been, who helped us, or how we had escaped. We were not even allowed to discuss the details of this event with anyone, not even family members. The conspiracy was to protect the people who had helped us and saved our lives. If they had been caught by the Germans, they would likely have been killed. Even after the war, with the establishment of the communist regime, we were worried that if we mentioned the names of those Albanian heroes who saved our lives, they would be killed. Later we learned that one of the partisans who helped and sheltered us, Kostaq Stefa, was imprisoned immediately after the war and eventually executed by the communist regime. I am quite sure that without the help of the Albanian people, we would not have survived that winter. Memorie.al

#CommunistAlbania #ForgottenHistory