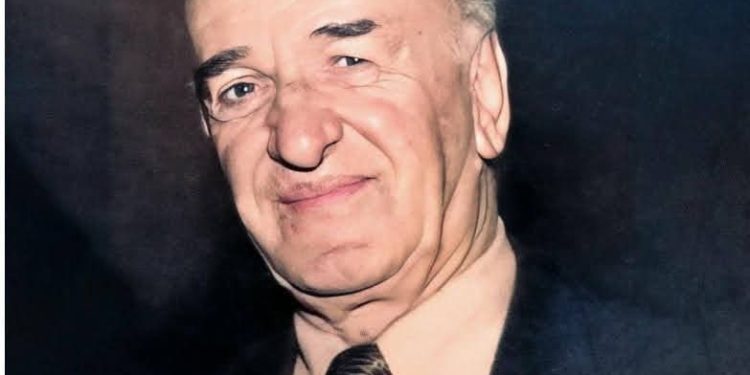

By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirty-six

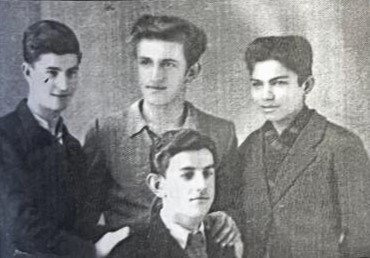

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

A plane that passes at night over the city sky, along with the hope of freedom, awakens in my soul a lot of joy and longing. That night, as during the previous nights, I was patiently and soulfully pushing through my endless hours, in anticipation of an imminent death, which still did not come and did not come.

It might have been two weeks since I was addicted, when all of a sudden, the echo of an airplane in the sky of my city heading towards the lake, woke me up from my wandering state and made me, out of wonder and emotion, with a heavy heart and a special longing, listen to that echo, which the further the airplane moved away, the more it grew weaker and took on notes of melancholy, until finally, somewhere far away, it faded and dissolved in the night, leaving in my soul those impressions that to someone imprisoned near death, sound like a cry on the verge of victory, such that in my case, it was as if they were telling me: “Communist tyranny is counting its last hours”, or “Goodbye soon to freedom”! etc. etc., which fill so many with a truly heroic enthusiasm.

I was just instinctively convinced that the political changes in our country were connected to Yugoslavia, even though I had no idea about the breakdown that had occurred between the two countries, something I would learn about after a few more months had passed. However, there were some indirect clues that led me to believe that something had begun to move: Ali Xhunga, not in vain, had warned me that “they would slaughter us in prison, before our Anglo-Americans came to Albania”.

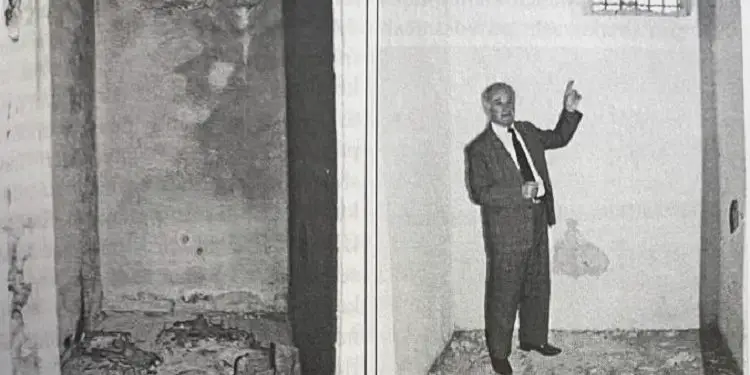

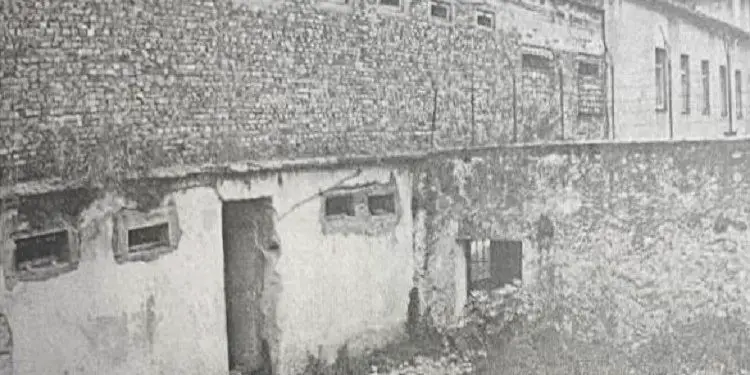

It was also several days since every morning, as well as in the afternoons, the sound of automatic rifles could be heard somewhere in the direction of Zalli i Kirit, and one day, while going “for questioning”, I had the opportunity to see soldiers and civilians with automatic rifles in their hands, who seemed to be going for training. In addition to the above, during those days, numerous arrests had been made so much so that the dungeons that had been filled with prisoners inside, had been filled with one, two, and even three more. Even along the corridor and in the small square in front of the W.C., I would see new prisoners, chained hand and foot, standing in a circle covered with blankets, so that they would not be distinguished from us when we went to the W.C. for questioning, and so that they would not see us either.

In the form of two large turtles, they, out of fear of the policeman who was there with an automatic rifle in his hand, did not come alive at all. However, one morning I was able to distinguish the student Mikel Muzhani, when he moved a corner of the blanket with which he was covered, revealing a little of his face, on which occasion I was struck by the size of his wide-open eyes, which expressed terror and curiosity, as well as his desire to make himself known to me. All this strengthened the suspicion that there could be a situation on the verge of change.

I am obliged to state once again that without having been a prisoner I, one cannot understand many of those special psychological “moments” that, in certain situations, are created within the world of a prisoner, that is, when, so to speak, on the verge of death, extraordinary human qualities awaken. The passage of a plane at night over the city of Shkodra, heading for Yugoslavia, I, as a prisoner and in the situation I was in, could hardly have expected to take the plane for “foreign” and “clandestine”, and its echo as a “message” for a people under dictatorship.

I can say that in those very special moments for a human life, I have experienced such a spiritual state and a need to express it in the most extraordinary words, which can never come in ordinary times. However, as my only and last wish, I would have, on that occasion, to be able to greet warmly and with the most beautiful words of farewell, my family, my friends and the entire city, which seemed to me to be counting its last days under communist tyranny. We have had the opportunity to read with what dignity and stoicism people of honor and idealism have defied death and that the cases when before death they were allowed to write letters, have sometimes resulted in artistically being true literary prose and this, for the sake of a very elevated moral and spiritual state, for the extraordinary qualities that in those last moments the endurance and act of sacrifice inspired in them.

How did the once-beloved and capricious Marie Antoinette die and how did she write her last letter? Where did she find all that moral strength and what did she do so that before the guillotine her letter was both in style and in content, exactly as her mother with great moral and cultural demands, the aristocrat and erudite, Maria Theresa, had vainly desired for many years? What did the young French anti-fascists do to write such wonderful letters, and precisely in the last moments of their young lives? And did not Albania, especially during the last war, realize models of heroism on the part of its sons, such as, for example, the case of a Manush Alimani and many others, and did not their letters, when they were able to be written, express several times in a concise manner, a poetic beauty of their souls?

But during communism, when hundreds and hundreds of idealistic and brave young people were tortured and killed, what would they have written before their death, if the communist dictatorship, like other dictatorships, had allowed them a piece of paper and a pencil on that occasion? (What kind of letters would Qemal Draçini and Ndue Pali, Muzafer Pipa and Ndoc Jakova and friends write in such a case?

In those moments of longing and joy, images after images passed quickly before my mind, which was flying to the sad people of my family and some of my friends still not freed from the fear that I would take them out. Ignoring pain and nothingness, I gathered all the remaining strength and hanging as I was, I forced myself to climb up to the window, beyond which stretched in darkness the invisible horizon of my city, through whose sky, a foreign plane had just passed, which in some way had left behind the curtain to take off.

Thus I, holding tightly to the rope with my hands tied and crushed between pulse, I was able to climb up to the window, but when I was about to put one knee on its scarp-like sill, my strength failed and I fell down with a piece of rope between my hands that was bleeding. Although I was in a lot of pain, I, as on other occasions, slept where I had fallen, to hang myself again after a few hours, when the prison guard found out that I had broken the rope again. I would hang myself, but not between my pulses, which had now turned into living flesh, but between my shoulders, under my armpits.

Rexhep aga seemed to be talking to me through the fast ropes. It must have been a month since I had been a prisoner, so it must have been early September, since the nights were so cold that I was shivering every night after midnight and especially before morning, since even in my teens I still had nothing but a thin shirt without buttons and a pair of panties, with which I constantly had problems, since they did not fit my waist, even though the policeman would sometimes wrap a string around it so that they would not fall off.

After three or four days, the rope even under my armpits began to cut like a razor and the fresh wounds burned like fire. Other wounds had opened up on my body, because Ali Xhunga had recently dragged me twice and laid me on the wood. My condition was what it was, and on one of those nights it dawned on me that the husband of a first cousin of my mother’s, namely Rexhep Llazani, a gentleman from Shkodër – father of several sons who had returned from the wars, who enjoyed support and positions from the regime, but who had not approved of my imprisonment – this Rexhep aga, thanks to his religious vocation – as after me -, had managed to connect me with some threads that I was taking to “smear”, and which, secretly from the Sigurimi, he had been able to extend into my dungeon. I was stunned by the unexpected, but to be surprised – given the deep hallucinatory state I was in – I was not surprised.

It was past midnight when, behind me, he, so as not to be overheard by the Sigurimi people, was calling my name several times in a row, as if in a low voice: “Ahmet, Ahmet, Ahmet”! And his careful, almost silent speech reached me as if articulately and deafly. After I responded with great courtesy and gratitude to his call, he told me that he was going to the mosque on the street, somewhere in front of the Sigurimi building. The purpose of his coming there had been for me to stop suffering, to give up resistance, as if it were a wrong path that, according to him, was leading me towards death day by day!

For about two hours, Rexhep aga “gave up and down” with me, begging me like a child to stop the “process”, while I, never taking my eyes off the counter, lest the police come and endanger Rexhep aga, in a light voice so that it would not be heard in the corridor or outside, would respond to him with great respect for the trouble he had taken, and would say to him: “I can’t, Rexhep aga, I can’t”! “Thank you, Rexhep aga, but there’s nothing I can do”, “I’m sorry, Rexhep aga, but I…”! etc.

Since the wounds under my armpits were burning very much, I couldn’t move, moving around constantly and as always, not knowing how much pain I was adding to myself on that occasion. The rope, as on other occasions, as a result of my constant movements, would wear away from its friction against the window sill, and that moment would come again when it would break, and precisely at the moment when Rexhep aga was about to part from me.

As for me, the rope, as a divine gift to the religious Rexhep aga, was the same piece of rope that I had held in my hands without remembering for several hours that it was the rope with which I had been hanged. I was left with two pieces of it in my hands and I did not know what to do. I was worried about Rexhep aga. I did not even sit down, although I needed to lie down so much, Rexhep aga did not want to take the risk. I felt quite demoralized by his fate. Where could I hide those ropes, as God’s gift that had been for Rexhep Aga?

With them in my hands, I once sat down under a corner of the wall, and to see them, I placed them behind my back. No matter how much I was sleepy, for fear of being seen, I did not even lie down to sleep like other times. So serious would be the poisoning of my brain, that even though the last hours of the night passed and the light was coming out, I would still continue to stand nailed to the spot, with ropes supposedly masked by my body.

The first to arrive there was Sergeant Mënyri, who when he saw me, smiled and then said: “Have you broken the rope again?”?! He did not go inside the dungeon, but when I told him that; “The ropes belong to someone else, not to you,” he would smile once more, and apparently, having understood my situation, he would leave without speaking to me. After Menyri, Captain Muslim arrived, who also treated me well. After this man also received the same response from me about the rope, but without having understood my situation like Menyri, he spoke to me shaking his head: “Come on, come on Ahmet, did you start too?”

A chance to laugh!

Two of the policemen who served in that prison had the same name, “njani”, among whom, the older one, although quite serious, was good, who limited himself to his duty as a guard, while the other Qani, young in age, blond and with a thick voice, who had been more or less good, would change for the worse, as soon as he went from being a simple policeman to being promoted to corporal and temporarily replacing Ismail Lulo, who had gone on duty in Kukës. This Qani had grown up immediately, for the slightest reason, he had started beating the prisoners with his belt, screaming like an animal.

It was a rule that when prisoners were taken out for need, the policeman on duty would temporarily leave his guard post in the corridor, and with automatic rifle in hand, go outside, taking up his position at the gateless entrance of the small courtyard opposite the W. C., while during that time, Qaniu in the corridor, as if after the turn, would take prisoners out and put them in the cells. As is known, I was taken out last, as I was the most helpless.

Regularly, when they opened the door of my cell, the prisoners’ exit to the W.C. would be considered closed for that turn as well: the policeman from outside would return to his post and, together with the prison manager, Ismail Lulon, would await my return, which would always be delayed. I went out twice, not because I needed it like the other prisoners, but to briefly free myself from the hangover. I walked hunched over and held on to the wall.

Qaniu, as a new prison warden, would initially take me out as the last in line, and not like Ismail Lulo the last, so one morning, as I walked, holding on to the wall, I noticed a small basket of black grapes with a label with my name on it. It was the fruit that the family, along with the daily meals, sent me, which had been feeding the “Deaf” police for a long time, but never me.

I was dying for a drop of water, and taking advantage of the absence of a guard in the corridor, I bent over the basket with difficulty, quickly dipping both hands into it, but I couldn’t even get a single grape out, because as is now known, my hands, for many days, had not been able to get together or hold water. One day later, while I was going to the W.C., in the corner of the prison outside, I saw the small kettle full of water and the large cup on it. As I always die for water, I decided that on my way back, as a matter of course, I would definitely drink a cup of water in front of the policeman, even if he hadn’t gotten inside by then.

So on the way back, when I was near the water kettle, I looked at the policeman in front of me for a moment and quickly bent down, inserting the index fingers of both hands into the spout of the water bottle, which I filled with water and began to drink it “hurtha-hurtha”, while the policeman with an automatic rifle pointed at me, out of fear of Qaniu, threatened me by shouting loudly, as if something big had happened; “Throw it, throw it, I say, throw it or I’ll kill you, throw it”! – the poor policeman was screaming and saying nothing, but in the meantime, the scandalized Corporal Qaniu had arrived running, who with the stick of a broom that he had found near the kettle, began to beat my head, while I, despite the pain in my head, would not remove the water bottle from my hands without letting him suck the last drop of it.

Only when I had completely soaked the safe with water and after I had slammed it on the ground, with both hands raised high, did I try to grab Qaniu’s stick, and for a moment I managed to place both hands on it, but despite my anger, they still wouldn’t grab and hold. Qaniu, for his part, frightened by any attack from me, moved a couple of meters away from me and every time I moved my knees as if I were attacking him, – even though I could barely stand – Qaniu would move away.

It was really funny! The other policeman, who had taken this matter very seriously at first, now placed behind Qaniu’s back, could not bear it without laughing. I returned to the dungeon with a quenched thirst, but with severe pain in my head. Surprisingly, Corporal Qaniu would not take me for anything that day and after that. During the month of September I had simply turned into a mass of rotting flesh, which stinked like a crock. Ismail Lulo, who twice a day was busy untying and tying the rope, but as long as his actions inside my dungeon lasted, he would spit on the ground,.

And so it would happen every time a policeman opened the door for me, even for a moment. From that time on, two policemen would put their arms around me and sometimes even carry me like a child, whenever Ali Xhunga called me, and on the way to him, they would walk most of the time with their heads to the side and occasionally patting the ground. Whenever they took me out for a need, I would not walk holding on to the wall as before, but on my hands and knees, that is, with my knees and hands on the ground.

I would sleep lightly day and night, as I needed to, as well as for breathing. Most of the time, I would go barefoot without my panties on, because due to the pain, – as we have already shown – I would move a lot, so that my panties, both from the weakness and from the movements I made, would slip off the string with which the policeman had tied them to me the night before. It happened that Ismail Lulo, or one of his deputies, even though they saw me naked when I went to the toilet, would tell me: “Come out as you are,” while I, although I generally only went out to escape hanging for a short time – as a sign of threat, would answer: “If you don’t put on my panties, or if you don’t cover me with something, I’ll fuck you here”!

In such cases, they would give me a white mattress sheet and I, wrapped up like a “dervish”, and with my hands and knees on the ground, would go to and from the toilet, slower than a turtle. As much as I was determined to endure any torture until death and not to end the trial, Ali Xhunga would have been equally determined to torture me, as long as I had not gone through the trial. Me and Ali Xhunga, like the “ends of a rope”, in Migjeni’s poem “Murgesha”. Memorie.al