By ANI JAUPAJ

“When I was about to give birth to my daughter, I found myself at my brother’s and the maternity hospital of this sector did not accept me, they told me to go to Lushnja, but I did not make it, because I gave birth on the road…”/ Shocking testimonies of Abaz Kupi’s daughter

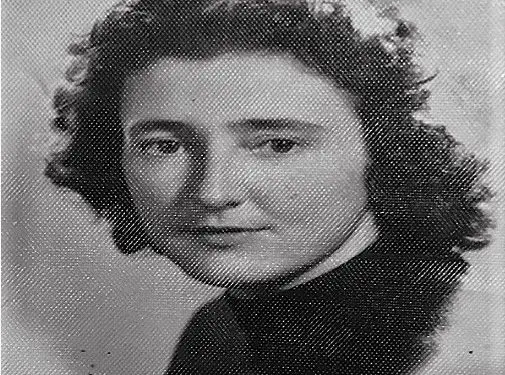

Memorie.al / Bad childhood. Bad youth growth. Threshold of bad old age. Not a memory to contain, even a feigned smile, in all these stages of life. No hope that tomorrow would be better. A child who grew up running ‘stealth’, at night through the mountains, to see even for a moment his father’s eyes, did not have the luxury of hoping for a sunny day. And, since the sun is visible in the morning, fate seemed predicted…! Even today, 25 years have passed since Hyrie Kupi Dosti first breathed freely, it seems as if his eyes are red from constant tears…!

Even now that at least her children, the ones she dreamed about carrying the pile of wood on her back, are better organized, the worry of 45 years of exile has not passed, and there is no way it will pass. The memories of every day in this era of life, make Hirije that in every word he utters, he is permeated by vibrations of emotions, which only facial expressions, voice, eyes, can describe.

No matter how hard one tries to understand and convey the pain, they will never be able to reach the level of reality. Not coincidentally, it is not easy to distinguish Hyrie’s accent. Very few details remain, from the spoken language of the early origins of the father, Abaz Kupi, and grandfather Hasan, from the “Varosh” neighborhood of Kruja. The accent is mixed with the tones of deep Labëria, as with a softened muse, adapted from the long and endless stay in Lushnje, so that you can never reach, in the real name of the place of origin of this lady that with all the suffering shines through the wrinkles, nobility.

As if the places were not enough, where she and her family members (mostly women) have moved to remote parts of Albania and not only, years later, when she tied the knot with Viktor Dosti, another convict who suffered isolation by her side, he began to visit the country’s prisons, where they were and where they were not, to help his brothers-in-law. To see, when the street money was made, the 4 children of one of the murdered brothers. However, no matter how much suffering they have gone through, it is strange the spiritual connection and communication that these people left from that regime have with each other. It is the closest connections that you want to see. As before, they continue to live in the same apartment entrance, donated by the state, with the same care, which they have been used to since the beginning of time.

Even when it’s time to talk to Hyria, the two brothers of her husband, Viktor, who is no longer alive, stand there for every memory barrier that Hyria has, to overcome or remember. The story is all fused into one. Among the literature in foreign languages, inherited from the Friends, predecessors (mainly artistic), which covers the entire white surface of the walls of the salon, there are also portraits of warriors. On one of the columns of the wall, the photo of Abaz Kup, together with his close friends, and his work hangs proudly, while on the other, Hasan Dosti, as the owner of that library, which he had built for the third time in a row.

He was not depressed by the burning of the first two libraries, once by the Germans and once due to an accident. Today, the family members are summarizing all the notes and studies that Hasan did about Albania, to leave the library to the Institute of Historical Studies for the benefit of researchers.

It is not only this paradoxical, that the Friends of Kupaj are offering help today, while they have been suffering and looking for it all their lives. Mrs. Kupi-Dosti, after all the years of isolation under barbed wire and barbed wire, is now one of the freest ladies in the country. It has nothing to do with allowing everyone to cross Europe’s borders. She has been holding an American passport for a long time. So it knows no limitations, of any kind. He walks, visits his two children, his grandchildren in America, and all his relatives, wherever they are. At least now, you can…!

Mrs. Hyrije, I don’t know how much a 5-year-old child can remember, especially in your case, so many years have passed…?! On the other hand, I have the idea that suffering is not easily forgotten. Do you remember something from your family’s first deportations?

I have spent my whole life in exile, and not just one kind. The first internment was that of Himara, and then it was the turn of the period in Italy, where we were taken to the 40s. Then, during the period of the Italian-Greek war, we were sent to Brindisi, where we spent a short time in prison. It was a time of bombing, we had to stay isolated. Later, they took us to Siena, where we stayed until 1942. Then they sent us away.

Why what changed?

Nothing changed; it was their strategy to use the father, in case he would agree to make compromises with Italy, for the benefit of the war. But they saw that this did not happen and they took us to Gjirokastra.

Apart from the geographical transfers, what feeling does that time bring you?

In fact, we have not lacked good treatment from the Italian citizens. They saw us as a politician’s family and, as a result, they respected us. There were other concepts on their part, unlike the Albanians, regarding the treatment of a family with a name. Moreover, regardless of politics, they appreciated my activity and helped us as much as they could. I did the first grade there, but from the language, there is enough left to understand and get along. All from the memories. A small child cannot store many things in memory, also because great suffering would come later.

However, I do not believe that they treated you so well even when they returned you?

When we went to Gjirokastra, I was 9 years old. I remember the horror I saw and heard in my mother’s eyes, when she saw the prisons in the fortress of Gjirokastra, where we had to take refuge. They were old medieval buildings, from the time of Ali Pasha Tepelena. She kept asking, in tears, to take us out of there. How could a woman stay there all alone, with small children?! Then they took us away, we took a place for some time in the hotel.

It was Dr. Sazani, who was later shot, took us and sheltered us in his house, where we stayed for 1 and a half years. Even this phase, compared to the later one, was to some extent human, because the doctor appreciated and appreciated us, just as the citizens of Gjirokastra did, although not demonstratively.

Where was the father in the meantime?

Father was on the mountain. At the time of the war against the Germans, he was the main one in the Kruja war. While he was fighting, the women were staying illegally, with his father’s relatives and friends, in Mat, Martanesh, where his father’s area of influence was. This is where the dark period began. We hiked the mountains, at night, to escape from the Germans. We used to go from one house to another, where we were welcomed by my father’s friends, always secretly.

These lasted until ’44, what happened to all of you then?

My father, together with his two brothers, escaped towards Italy, in a boat, in miserable conditions, that it was not known whether they would be able to cross the other coast or not. And in fact, they would not have been able to if his friend, the English missionary Julian Amery, had not organized his rescue, so as not to fall into the hands of the communists. We learned later that the journey had been dangerous; all three would have drowned if they had not been saved.

While you…?

We jumped into the big communist camp. We were first interned in Tepelena and, on the way there, disasters began that they would not have foreseen. During the transfer of the Berat camp to Tepelena, the car with the internees crashed in Gryka e Këlcyra. My sister, Maja, died there, along with her husband, Fadil Petrela, leaving 4 orphaned children. Of all the passengers, only those two died. They didn’t even let them bury them; no one made the slightest move. The internees dug two pits where we were and buried them. One of the children, the youngest, my sister had by her side, it was a wonder and luck, how she managed to survive.

Did you see all these scenes with your own eyes?

How many people have died and crawled, in the eyes of their relatives! It would be better to be imprisoned, you knew you were suffering yourself, but to see the people of the family, giving their lives before your eyes, who walked bent over from hunger and, from their legs, which were about to break.

By this time you had grown up, you must have fuller memories?

Not only because I had grown up, I was almost 16 years old, but because the time of Tepelena was the most terrible, beyond any human imagination. It never occurred to us that we would ever live in those army barracks, surrounded by barbed wire and guards. Families were separated from each other by curtains. Tepelena had a very harsh climate, it was bitterly cold. There were no clothes, they were very worn, so much so that they were torn from the women’s bodies (for them it was more difficult) and they made blankets to wear.

I remember like now, when one of the co-sufferers, her dress fell off from wear and tear while walking and they had to wrap it up. We ate only oatmeal, with worms or beans. Hell, Tepelena’s water was too solvent and the food didn’t last long. But could you stay on your feet with these, after a whole day of work?! I had to take the food ration to a sick friend of mine, and when I see the surface full of worms, I thought, what am I taking?! I tried to remove that horrible layer and only scoop out the liquid, if not any of the beans.

Where did you work, what did you do?

We worked on the Lazarat Mountain, which was 2 hours away on foot from the camp where we lived. We were loaded with wood on our backs, to take to the officers and their families, (they were the ones guarding us), to warm up. I remember once when I was running away, a policeman saw me, who seemed to him to be less busy than the ‘norma’, and threw some more sticks at me, saying: “You deserve it; you are the daughter of Abaz Kup”. My brother shot there and fought with the policeman, telling him that I didn’t even know my father. I had only heard about it.

As far as I understand, Tepelena has been the most difficult time…?!

Extreme hunger, bitter cold, indescribable in words. Besides these, tragic events followed each other. A Mirdira mother, after returning from the mountain where she had unloaded wood, had no breast milk to feed her two twin children, who died in her arms from hunger. After this event, she went crazy, until she herself died shortly after. Another case was that of Muharrem Bajraktar’s wife, an elderly woman, who also died from constant hunger.

I myself, I remember, walking one day with legs that were about to break off and hungry, to the limit of measure, I was praying to God, saying: “Will I ever be able to get enough of bread and not get sick?” legs”?! The pain was also increased because of the shoes we were wearing, they were wet, the water seeped into the legs, and moreover they made it difficult to walk.

The name of this period was only “Bread”. When did this horror end?

I was separated from my family after that. While my sister, who had passed the working age, continued to suffer in that hell, I was taken elsewhere. It was a group of people they sent to Vlora, to build the new Vlora prison. There I prepared the prison of my future brother-in-law, Leka, as I would learn later. The prisoners made the prison of the prisoners! Imagine young women working with mortar and bricks to build the walls that would isolate people. After the ‘realization of the plan’, this same group was transferred for a short time to Tirana, for the construction of the Brick Factory. Then, some new decisions somewhat alleviated the situation.

What were these decisions?

At the end of 1953, beginning of 1954, with a new government decision, the treatment of internees changed. With the death of Stalin, the ill-treatment was softened somewhat, Hungary was the first to implement it, but the change was seen in other countries as well. From the wire camps, they transferred almost all of them to Lushnje, distributed in different sectors of the Lushnje farm. The conditions also changed, we worked as farm workers, although the discrimination was obvious. But, compared to the time of Tepelena, these were not noticeable. There was fatigue of course, but the conditions were no longer so miserable. Hunger was no longer the same.

In addition to changing conditions, you were also in a phase of change. From a little girl, with a tired wooden back, you had become a young lady already. New sensations come to light…?

Dreams and thoughts of better opportunities did not often occupy you at that time, because your mind was elsewhere. It was a constant struggle for survival; it was very much even, that we managed to somehow improve the living. But on the other hand, we didn’t know how long it would last, a new decision could overturn everything and the situation would go back to how it was. At this time, we had become a group of families that lived together, such as Dosti, Mustafa Kruja, Kaloshi, Mulleti, Pervizi. They created for us, as the best-mentioned families, a new camp, deep in the field of Myzeqe.

This is where the first crossings of views with Victor began?

It was a coincidence that my brother Bardhi had been in prison with Victor and they loved each other very much. Thanks to the evaluations of the families, one with the other, the krushkirs were also created. Although I don’t want to deny it, that I had sympathy for Victor and I always singled him out from others. Thus, in that whirlwind of suffering and pain, a troubled feeling was born for the first time, unlike any previous experience, which would soon take full shape and be crowned with marriage.

Tell me if it’s too much to ask for some little ceremony, just to remember that day unlike any other?

There was no talk of ceremony, or of details of any kind to make it seem like a special day. We couldn’t even think of them.

Pain and suffering seem to fade away, when you have someone to share it with…! Everything is seen and experienced differently…?

It is true, and not only for me but also for Victor’s family, which had gone through some of the worst disasters, because his mother and uncle were killed by the Germans, (November 17, 1944) the brothers were scattered in prisons and camps, the father, Hasan Dosti, had escaped. So for this whole marriage, it was like a renewal. It became the nucleus of a new family, where others who had been prisoners would come later. So it was everyone’s shelter. This kindness was increased even more with the birth of our children.

However, I imagine that the burden still fell on you, because you had to follow your husband’s brothers to help them, or even yours?

I definitely had to. I was going to Burrel, in Laç, where Viktor’s brothers, Leka and Tomorri, were imprisoned. Once, when I was going to visit my brother, through those ruined roads, I thought that, since the road went well this time, (the idea was that I escaped alive), the next trip, I am taking the girl with me. Even if the car were to overturn, it would be better if we ran away from this world together; otherwise who would I leave it to…?! I didn’t want her to go through the suffering that I had gone through alone. Because the fate of the men of the house was unknown.

In all these years, you had news from your escaped brothers and father, what had happened to them?

We had a very easy correspondence with my brothers, but never with my father. Through secret addresses, we tried to exchange a couple of letters, but very rarely, even they sometimes came and sometimes didn’t.

How long had you not seen him?

It was a single meeting on the mountain, after we were released from Gjirokastra. Father wanted to introduce the family to his friend Julian Emery, (British officer) and gathered us. Imagine a child, at night in the mountains, in constant fear of killing his father, how much can he remember from all this. I remember seeing myself with my sister in my eyes, scared, hiding, and trying, as far as we could understand, to protect my father. That was the first and last meeting with him.

How did life continue in Lushnja?

After 1974, things were sometimes tightened and sometimes loosened. A wave of arrests began, which made us go to work in sweats even during the summer, for fear of being arrested and, having something to wrap ourselves in, in the dungeon. At this time, they also arrested my brother, Bardhi, leaving the children and his wife alone, whom I had to help, as much as I could. It wasn’t much help because I barely managed to save even the travel money, but at least I was going.

What if you needed health care, could you have it?

It was limited, dismissive. The worst case was the birth of the daughter, Arta. I found myself at my brother’s and the maternity hospital of this sector did not accept me. I had to go to Lushnja. I didn’t make it because I gave birth on the street, without anyone’s help, in the presence of my brother and my husband. On the other hand, even doctors have been under constant pressure to offer help. Later, I admitted the girl with jaundice to the hospital, where Dr. Çabey, he made sure he was treated well. They considered this treatment of a 3-year-old child a favor for the declassified and held an unmasking meeting.

Whose mind was waiting for you that you were on the verge of freedom?

I remember one time I cried when I saw my daughter, only 14 years old, who was physically disabled. And when he sees me so depressed, he tells me; “Mom, don’t worry, because I will work for another 5 years.” The saying of my little one fired a prophecy.

Did you connect with your relatives after the fall of the regime?

I went to America, but found only the brothers. The father had died during an operation in ’76. Each of them had created a family there; my son has already gone too. Then, in 1992, Victor’s brother, Luani, came from America. Unfortunately, they didn’t meet his father either. They only managed to hear each other’s voices, because he died in ’91. Afterwards, mutual visits were made, because my brothers also needed to come.

Most of the people, you left out…?

Yes, I only have one of the girls here. Yes, I also go often, I stay there for 2 or 3 months, but I return again. My roots are here. But I have the opportunity to go anywhere I want…!

Who is Abaz Kupi?

Abaz Kupi (Bazi i Canes), was born in Kruja in 1891 and was raised with patriotic feelings. With the formation of the national government of Lushnja, together with Bajram Curri and Ahmet Zogu, he participated in the war against the Montenegrins in Koplik. He served as commander of the gendarmerie in Kruja, with the rank of captain. Later he was promoted to major and served in Durrës. In the days of Italian fascist aggression against our country, on April 7, 1939, Kupi led the resistance of the military department in Durrës. With the invasion of Albania, he left for Turkey. With the help of an English officer, he went to Yugoslavia to form the Resistance Front with the support of the English Embassy in Belgrade. After the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Germans, together with Gani Kryeziu and Mustafa Gjinish, Kupi returned to Albania to organize the resistance against the invaders. Abaz Kupi was an honor to the organizers and main participants of the Peza Conference, held on September 16, 1942, and was elected a member of the Anti-Fascist, National-Liberation Council.

With the idea of expanding and strengthening the common front of the Anti-Fascist War, he became the initiator of the Mukje Conference held on August 1-2, 1943, to achieve cooperation between the National Liberation Front and the National Front. When Enver Hoxha rejected the Mukje Agreement, Abaz Kupi left the Front and in November 1943, formed Legality. After that, the leadership of the Albanian Communist Party ordered the physical annihilation of Abaz Kup. However, he avoided the civil war, instigated by the communists. At the beginning of November 1944, he left his homeland. In emigration, he became active in the “Free Albania” Committee. /Memorie.al