Memorie.al / If you visit the Hamburg cemetery, Ohlsdorfer Friedhof, today, you will come across the grave of Otto Witte (16.10.1871 – 13.08.1958). On his headstone, the inscription clearly reads: “Ehemaliger König von Albanien” (Former King of Albania). However, in the registry of notable people, his profession is listed as “Exhibitor” – a man who performed shows with his mobile home at Germany’s annual fairs. What is the connection between this noble title and such a peculiar profession?

“Yes, it is true: I was King of Albania for five days; a real King, with a throne, servants, and an army, as befits a King,” Witte begins in his 1939 autobiography, 5 Days King of Albania. He notes that Albania is not some remote Pacific island or a Central American republic, but a “normal country in Southeast Europe” with a population of one million.

A Tale of Two Germans

It seems Prince Wilhelm zu Wied was not the only German to lead the Albanians (Wied reigned for six months in 1914). Another German claims to have ascended the throne before him. While contemporary historical evidence in Albania is scarce – perhaps due to the phonetic similarity between the names Witte and Wied – this story is cited in dozens of European articles as one of the greatest adventures of the 20th century.

In early 1913, Albania’s fate was being discussed in the chancelleries of London, Vienna, and Paris. The Conference of Ambassadors had declared Albania an autonomous principality under a foreign prince. While the Vlora government sent appeal after appeal for a head of state, Esad Pasha was maneuvering for power in Central Albania. Amidst this chaos, one name was frequently mentioned: Turkish Prince Halim Eddine, the Sultan’s nephew. This political vacuum provided the perfect stage for Otto Witte.

Who was Otto Witte?

Born in 1871 in Berlin, Witte began earning money as an artist and magician at age eight. He spent much of his life as a wanderer across Europe, America, Africa, and Asia Minor, changing professions from construction worker to animal catcher and waiter. Though he had little formal schooling, he had a natural gift for languages and spoke Turkish fluently. In 1912, he joined the Turkish army, eventually rising to the rank of Major.

The Five-Day Reign

According to Witte, while in Constantinople in 1913, he met an old friend, Ismail Arsim, who worked for Turkish intelligence. Learning that Albania was waiting for Prince Halim Eddine, Witte conceived a daring plan: he would impersonate the Prince.

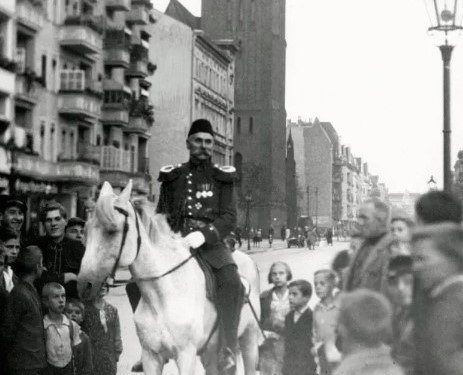

He sent two successive telegrams announcing the “Prince’s” arrival. On February 15, 1913, wearing a uniform rented in Vienna, Witte arrived at the Port of Durrës, accompanied by his friend acting as an adjutant. Due to his resemblance to the real prince and the pre-arranged telegrams, he was crowned. As a “King,” he hosted receptions, organized military parades, and was even offered a harem by his loyal subjects.

The news spread worldwide via international correspondents, eventually reaching the Sultan in Istanbul. The Sultan was baffled, knowing his nephew was actually on vacation in Vienna. When the real Prince Halim Eddine sent word from Vienna expressing his astonishment at the news from Albania, the fake monarch knew his time was up. Witte fled just in time to escape an arrest warrant from Esad Pasha, reportedly aided by the girls of the harem, and escaped by boat to Bari, Italy.

The Post-Royal Period

This story became the central theme of Witte’s later life and his fairground shows. In 1939, he published his memoirs, written by his daughter, “Princess” Elfriede Witte. He even managed to have “Former King of Albania” legally added to his identity card.

The legal battle over this addition was specific: he couldn’t use “Ex-King” (which implies a legitimate former monarch), but “Ehemaliger König” was allowed because he had technically functioned as a king under the name Halim Eddine. Witte took his “royalty” seriously; in 1957, he reportedly felt insulted when Prince Rainier III of Monaco failed to invite him to his wedding to Grace Kelly.

Whether this story is a masterpiece of historical deception or merely a wild fantasy remains a mystery that Witte took to his grave. Today, only three things remain as “proof” of his adventure: his autobiography, his identity card, and his tombstone. Interestingly, his birth date – October 16 – is the same as that of Enver Hoxha, a coincidence that only adds to the legendary nature of his story. Memorie.al