By Taisa Batkina Pine

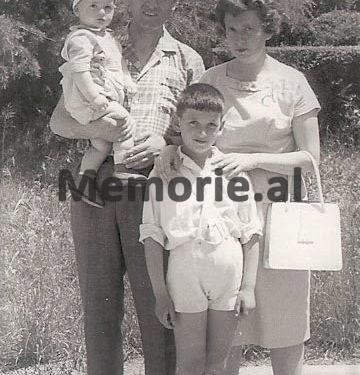

Memorie.al/publikon the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, and began life in the city of Tirana, where Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkina on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to 16 years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

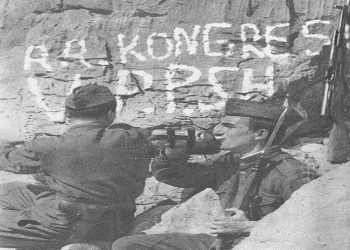

This is a memoir. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because… we fell in love! And let no one ever forget what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

There were few vegetables left in the garden at that time, so they strictly forbade us to take anything for ourselves. If they caught us, they would put us in a dungeon. Bajamja was on duty that day and we hoped she would not check on us. We put the cabbage in the bucket and covered it with a bag. But at the gate Bajamja checked us, put his hand in the bucket, touched the cabbage, but pretended not to find anything and let us pass. Service officers were responsible for all life in the camp, day and night. Many of them went unnoticed. Most I do not remember; only a few left traces in my memory. Usually the good or bad ones remain in the mind. Particularly wicked and filthy was Ramadan, a hated face with clumsy ears. He was a real sadist, he had nothing to do with killing a dog, and he experienced real pleasure when he kicked cats living in the camp territory. Once, during the appeal, he was hit so hard by a cat that ran nearby that it flew a few meters, crashed behind the wall and fell dead. We all bowed our bodies shyly; we remembered that now he would hit us too. Ramadan turned, cursed and left. When he was on duty, he forbade us everything he could, punished us, put us in jail. He could devise any excuse to cancel the meetings, turning back the people who had made the 20-kilometer charge to come all the way to the camp.

One hot afternoon Nadja and I were working near the command building. We were trying to pull a big stone out of the ground. It was hard work for our hands. A guard came out of the building, a young boy, who had just been brought to our camp. At the point of our futile efforts, the boy felt sorry for the two old and tired women, took the pickaxe from our hands, and immediately pulled out the stone. Immediately on the road appeared Ramadan. “What are you looking for there?” – scolded the guard. – Let them work… you found someone to help, enemies… ”! In our camp, elderly guards were often brought from the camps, who had to work for a year or two before retiring. Usually, these people were bored with that job and had no zeal, no desire, no power, to be strict, to shout or punish. Luckily for us, these people were just careless. But there were also good-hearted among them. One day we were working, under the scorching sun, at the end of a field; I cultivate corn. Aqif guard was sitting next to him. Where the brigade was working was the border of the territory. Aqif was an old man, silent, calm, we still did not know what a man he was, because he had just come to our camp. We were terribly thirsty, sweat was dripping, and those who brought water did not reach us… ran out of water on the way. (Water was brought in large cans and distributed gourd in the workplace). Suddenly we heard our guard yelling at the water holder. She recalled that the guard wanted to drink himself. He filled the can and the gourd and hurried to him. He ordered him to give us a drink and asked him not to run out of water anymore.

Another time, we were uprooting potatoes. Almond Guardian begs Aqif to allow us to take some potatoes with us. Aqifi accepted and told us to take 2 kg. Of course, we did not weigh them; we took as much as we could. Undoubtedly, there were worse, rude, savage guards who darkened our lives, but I do not want to remember them. Nazif was also a guard at the camp. He was a man with the moon, sometimes with humor, sometimes terribly wild. He performed the duty of economist. You could get paper, pencil or something to wear with him. I had seen several times, that he gave a piece of freshly slaughtered pork, or a little sunflower oil to some poor and hungry old woman, which was not few in the camp. But when he got angry, he became scary. The first few days after we arrived at the camp, we were stunned to see one of the imprisoned girls being beaten with a stick in the field. Another time, we saw him running to the camp and hitting with the ground of the soldier’s belt, the women sitting on the steps of the corps to escort a friend of theirs, who had just been released. There were also hired workers in the camp. They were strictly forbidden to communicate with us. In his little hut, a craftsman worked to repair our tools. Sometimes we would distract him and he would make tails for the pans we found in the trash, or he would repair our buckets, the pots. Of course, he did not help anyone, only those who he was sure would not report him. The cook in command worked Beauty, a simple and kind-hearted woman. How sorry he was for old Lena, who was in her 70s! Lena was not helped by anyone. They put him to clear the territory before the command. When there was no one around, Beauty would call the poor old man to the kitchen, give him something to eat, put a piece of bread in his pocket, and put fresh vegetables in the trash bin Lena took out of the kitchen. . Nadja also gave it to her to eat when she was working in the command territory.

Our camp is called “reductive,” just like Stalin’s reeducation camps. We had to be re-educated…! For this purpose were the commissars and the educational council, where they were prisoners from the corps of ordinary people. The council chairman had a small library, where you could pick up a newspaper or submit a request to the command. The main educational role was played by the commissars, black and white figures, most of them I do not remember at all. Their main job was to organize newspaper reading in groups. At first the newspaper was read to us in the field, during the lunch break. Everyone sat on the rocks or stones ate and, of course, heard nothing. Then they started reading them to us in the camp, right after work. Exhausted, hungry and unwashed brigades put them in the newspaper reading room. Usually I was left with a piece of space on the floor; we had no power to seduce young girls and sit on benches. As soon as I sat down, I fell asleep and slept like that until the end of the reading. I have to take revenge on my friends, no one reported me! Or maybe, the others slept too? Rather I remember the last commissar. He had served many years in the border forces and before he retired, he was brought to us. He was very obese, almost illiterate. He could hardly read, as he seemed to copy, barely read the first five words, then handed the text to one of the prisoners to read. I tried to stay away from him, but he often replaced the camp director and I had to address him for any problems, which always left a bitter taste in my mouth. From time to time the all-powerful, Operative from the district Security branch came to the camp. He often called us, asked us about completely meaningless things, but we knew that one of the questions usually aimed at the purpose of the call. We sat, listened intently, kept quiet, and tried to understand what was required of us. We were already used to the interrogations and knew how to single out the main one. Most often he tried to convince us not to write in the higher instances about our innocence. And in the end he asked us: “Hey, are you staying”? “Let’s stay,” we replied. “What do your wives say?” Usually I would answer: “They say nothing”! And once I said to him: “They say that we are here in vain and you should have released us a long time ago…”! After these words, I was immediately returned to the corps. I gave him this answer several more times and he… did not call me again.

Our camp

Our camp had two corps, one for political prisoners, and the other for ordinary prisoners. The whole territory was surrounded by barbed wire and towers with armed guards. According to the internal rules of the prison, we had to be strictly isolated; we were enemies, those… ordinary ordinances of power. The thieves, the usurpers of social property, were the prison elite, like the party elite in freedom. Many of these were women officers, responsible employees, they had trusted them, but they had not justified the trust, they had stolen. However, this did not prevent them from being privileged here, too, in prison. The camp yard was divided into two parts with barbed wire, but we could not be isolated. Between our corps and the entrance gate, behind which were the small command buildings, was a pretty large square. In the morning the brigades lined up there, before leaving for work, where they all worked together. In our building were the nursing home, the library, the account, the shop and the classrooms. All the prisoners passed in front of our corps and often entered our canteen. Albania is a small country and among the prisoners there are often people with whom you could have known in freedom. These could be neighbors, or factory workers, where you once worked, or acquaintances of your acquaintances. The first years in the camp there was an eight-year school for girls and villagers who had not been able to finish school before. They often came to us and asked for help, we did our homework together, we learned. Ordinary imprisoned girls began to treat us with respect. Among the ordinary prisoners, there were also interesting persons, like Lajda, an old, dry, tall woman. Lajda had authority in the camp. He had spent a total of 20 years in prison, had been tried 5-6 times for theft. They said that she had a good family, normal, husband, children, but she was adventurous by nature, she needed risks, to live adventures. She was a wonderful worker and organizer. The girls called him “underground” and obeyed him without words. He liked to tell his own stories, of course, decorating things at will. I have always regretted that her good qualities did not find better use.

Our connections with the ordinary were mainly of a commercial nature. In the camp almost everyone smoked and cigarettes were like. Currency. My boys, even though they knew I was not smoking, always put a few packs of cigarettes in the pack. We also bought cigarettes in the store, as soon as we were given the opportunity. Cigarettes were exchanged for everything: firewood, bread, all kinds of food, or clothing. The second winter in the camp was approaching. I passed the first one with an old, torn hood, which did not warm you at all. Another had to be found. It struck me that one of the famous girls had a gorgeous, black, thick hood. (We wore old soldier hoods). I learned that this girl was being released after a few months. A pack of cigarettes and the exchange was carried out. How well this hood warmed me up during my years in prison! At camp we were not allowed to wear household clothes. They gave us thick meringue underwear, t-shirts and brown dock pants. The color of the “suit” was of such quality that only after the first wash, the clothes turned beige, and after two weeks… white. Work brigades moved on the way to work in white columns. The villagers around the camp called us… “White geese”. Washing these clothes from winter dirt was a real problem. They were sewn in such a way that they looked like a sack. But women remain women. We, as much as we could, tore and sewed the clothes ourselves, by hand, as they looked a little better. The hardest part was working with the shoes. They gave us heavy, strong, half shoes. We could not remake them.

Our corps

In our building there were three rooms, two large, communicating with each other and at different times we slept 80-100 people and a small one, almost 12 square meters. In this little one we lived. There were five bunk beds in the room, with narrow passages between them, and two beds were adjacent. It was very tight. We slept on straw mattresses, and instead of pillows we used blankets filled with folded clothes, and two thin blankets. In summer it was terribly hot, up to 40 degrees, while in winter the average daytime temperature was 10 degrees; often shot frosty days -7 to -10 degrees, about 3-4 weeks a year. There was no heating in the concrete body. We slept dressed, threw up what we had, barely warmed up and could hardly sleep, even though we were very tired. I set a goal for myself: to sew a blanket. I collected all the rags that fell into my hands. The women, who were released, gave me t-shirts and torn pants. I made the belts and sewed them together. Within two years I managed to sew a vithanike, which served me long, kept me warm or cold winter days. Life in that strait was very difficult, but on the other hand, the fact that we were together helped us a lot. After hard work we lay in bed, in the soul we felt sad, everyone thought about their own affairs and worries, about their own people. Someone once proposed: “Do we play cities”? We played. We remembered songs, poems, invented contests, showed the books we had read, and remembered them better. This is how we had fun, relaxed our souls. Suddenly Nina’s dreamy voice was heard from above the bed: “Let’s remember the chocolates we ate in Moscow.” We remembered. But for the second time we refused; it was very difficult for us, the hungry, to remember such delicious things, that they were somewhere and reminded us of the world from which we were so unjustly ostracized.

In the first years of life in the camp there was such a rule: at night all the prisoners had to take turns guarding the corps for two hours each. It was hard when the service fired in the middle of the night. The guard should not sleep, he was responsible for the order, taking care not to steal anyone, in case of need to give first aid and call the guard. I have fond memories of this type of service…! At night, they all slept, almost all had heavy, restless sleep, and many spoke in their sleep, or groaned. Almost all of them had worked in the fields, they were very tired, and at night they were tormented by bad dreams, dreams of the evil that has befallen them, of bad luck. They had no time during the day and no one to complain to, and at night…?! Who knows what they saw in the dream, maybe the house, the children, and the family? Everything had collapsed, trampled underfoot. The husbands of many of them were in prisons, children in orphanages, or, even worse, on the streets. I have always felt bad during these night services. The two hours were not over. Later, fortunately, this type of service was canceled. We had a lot of forbidden things in the camp. It was strictly forbidden to carry a knife, even razor blades, or scissors. Sometimes you can get scissors for an hour, with signature. But how to do without a knife? We made the knives with the tails of spoons, forks, with pieces of sheet metal. We fried them with pieces of bricks, with stones, with them we cut the bread, we peeled the vegetables. The “forbidden knives” were taken from us, we did other things. When the brigades went to work, we all walked upside down, seeing that we could not find something we needed. We often found rusty razors, old metal saws. We carefully hid everything and brought it to the camp. With small pieces of razor blades we cut nails, even pieces of cloth. We had to hide the items found in the camp well. Early in the morning, before the appeal was made, we did everything sharp, suspicious. We put them in the cracks between the stones, in the ashes of the fire in the kitchen. They could check on us every day. Control was routine work. At first they were very serious, it seemed humiliating to us, when they arrested us, then in the cell, only… but we got used to it. They checked us, when we entered the camp, they touched us everywhere, and they turned our bags upside down. The brigades stood for hours in front of the entrance gate to the camp, waiting for the check to end. They checked our packages especially carefully. We cut the fruit in half. Everything in powder form had to be in plastic bags, liquids in plastic bottles, glass packaging was not allowed, because it had happened that during the quarrel with the quarrels, they used glass bottles.

All of this may seem trivial to you, but human life is made up of small things, and these small things were intended to humiliate us, to insult us, to extort from man even the last points of pride, which you can try so hard to preserve in prison. When a general check was made, almost all the guards entered the camp. (Usually only one was present, that of the service). They took us all out and it started…! They checked everything: beds, suitcases with food and bags with personal belongings, which were stored in the warehouse near the canteen. They all threw them on the floor, looked at the checked papers for a second before we picked them up, flipped through the books. Foreign, hostile hands left no room for entry. Of course, it could not be about notes, diaries all they all took them, threw them away, destroyed them. Then the control in the body started. Too often, if they found something forbidden, even a razor blade, they would cut you off. 59 We were completely forbidden to carry money in our pockets. All the money they sent us, or we earned through work, they put in the account. All purchases or any payments were made from the account. There they would give a check to the store and withdraw the money from the account. You only received the remaining money when you were released from prison. I do not remember how Natasha had earned 500 ALL, she would surely have embroidered something and they had paid her not in kind, but in cash, but with them she could not buy anything, because she could not put them in account. If they came to meet her, she could secretly give the money to her people, but at that time no one still came to Natasha. /Memorie.al

The next issue follows