By David Binder

-The American newspaper brings the profile of the well-known Albanian painter, who was punished with political prison and exile, due to modernist tendencies in art-

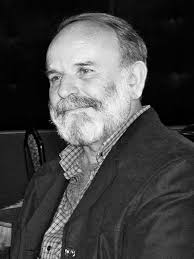

Memorie.al / About 18 years ago, Ali Oseku was declared one of the best designers of the country, a painter who had won a national competition and who had been given an order (medal) of honor, as the communist regime gave, to people distinguished at work, training and everywhere, with motivation; “For the growth of the revolutionary spirit”. He was only 28 years old. He was later condemned as a modernist who had fallen under the diabolical spell of Picasso, Chagall, and worst of all, decadent painters such as Jackson Pollock and Salvador Dali.

Arrest

Police of the Ministry of Interior, State Security) went to his small apartment and told him that he; “he was arrested”. They said that he had committed an ideological crime, “making propaganda for the enemy”.

“No”, Mr. Oseku objected. “Painting cannot make propaganda”. “The police ordered to burn 200-300 of my paintings. I had forgotten their exact number”, recalls Oseku. Then, after six months in the investigation, he was sent to prison. The sentence they had said to him was: “Dangerous for Albanian socialist realism and infecting young people”.

He was sent to the prison camp in Spaç, in the central part of the country, being punished under a regime of forced labor in the mine. “If you don’t meet the full standards, they mistreat you, locking you naked in a cell,” he recalls.

Modernism

There was a campaign against modern art in other communist countries at that time, but no one had such cruel consequences as those faced by Mr. Oseku and other Albanian artists.

“I was not allowed to paint,” he says, describing the early period of treatment under the rule of Enver Hoxha, who kept Albania on the communist path, since 1944 and staying on the course of uninterrupted Stalinist politics, until at his death in 1985.

A large statue of Stalin stood on Tirana’s main boulevard until last winter, when it was toppled by anti-communist demonstrations.

At the beginning of 1970, Enver Hoxha personally launched a campaign against modernism, in Albanian music and arts, which also victimized Mr. Oseku.

After four years in Spaç, the painter was released, but was again sentenced to hard labor at the “Party Steel” Metallurgical Plant in Elbasan, a heavily polluted town near the Shkumbin River, about 35 miles south of the capital.

Regardless of the function he held, like all the metallurgists of Elbasan, whose monthly salary reached up to 80 dollars, Mr. Oseku was allowed to resume his artistic activities. He created a circle of amateur artists, with his hard-working friends.

“Tribute”

They say that he could hasten his rehabilitation by painting according to the rules in the ideological style, defined by Enver Hoxha, but he started again with his brush against it. “I painted the heroes of socialist work,” he recalls.

“I painted Enver Hoxha twice, four meters high”. Mr. Oseku said that he had taken on such humiliating tasks “just to support my family of 9”. In total, he spent 10 years, under strict control.

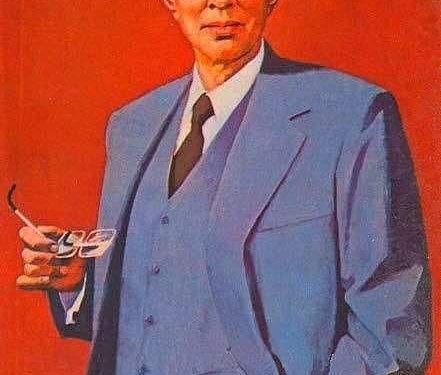

Mr. Oseku’s studio is in a wet coal cellar in the basement, 10 steps away from “Kongresi i Përmet” street, on one of the main axes of Tirana. He opened the rotting wooden door of a room lit by projectors.

On either side of the wall hung Osek’s last paintings,—portraits of his wife and brother, still wet, some landscapes, and some expensive nudes. “I have to beg and borrow paint tubes,” he says.

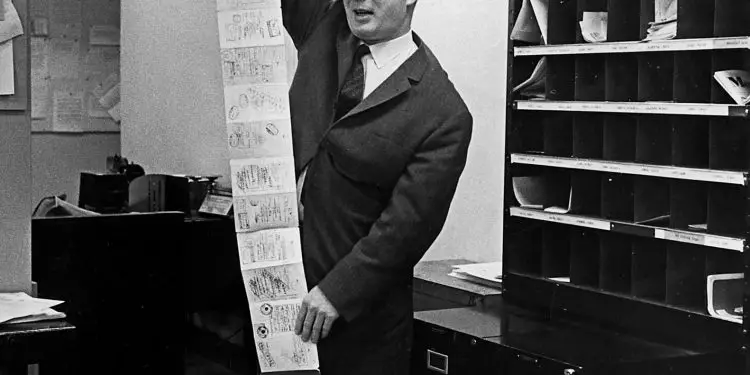

Mr. Oseku shared a copy of his latest work, a poster for the recently formed Democratic Party, which was used by it in the election campaign against the Communists.

“There was a “V” sign, a symbol of the anti-communist movement. Inside the V of Osek, there were green, fertile fields. Outside of it, fields of brown color, wrinkled and rough, symbolizing the communist rule. Memorie.al

The article was published in the “New York Times” on May 9, 1991

The title is editorial

Prepared for publication, Albert Gjoka