Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Zef Gjeloshi, originally from Tuzi, who, in order to escape the persecution of the Titoist regime, who had killed some of his family members, fled in 1950 and came to Albania. The tragic story of Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, originally from Triesi, Montenegro, in a memoir written by him entitled: ‘The Voice of Memories’ (‘Erik’ Publishing House, with an introduction by the prominent writer, Dritëro Agolli), where after describing some events during the period he lived in Yugoslavia, where he had the opportunity to meet with Marshal Josif Broz Tito when he worked as a volunteer in the construction of the Zagreb-Belgrade highway, he tells his escape how he came to Albania, where the paradise he had dreamed, returned to hell, suffering for years in prisons and internments of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha.

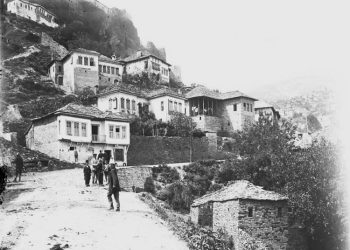

Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, originally from Trishi, Montenegro, was one of the hundreds of Albanians from Kosovo, Montenegro and Macedonia who during the years of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, to escape genocide and persecution of the Titoist regime of Belgrade, left their homes and came to their motherland, Albania. But their dream of a better life in the homeland of the ancients, quickly faded like a soap bubble. In their homeland, not only did they not have a good life as they had long dreamed, but a very tragic fate was reserved for them. Arrests, imprisonments, tortures, internments and a long ordeal of suffering in prisons and labor camps, having previously been accused of being UDB agents. This fate was also foretold for Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, who in his youth, when he was not more than 20 years old, left his family in Triesh, Montenegro and came to Albania. His whole life, which is a very tragic story, is masterfully described by him in a book he has titled “The Voice of Memories”. From that book, the preface of which was written by the prominent writer, Dritëro Agolli, we have selected for publication only a few passages that we are publishing in this article, along with a short history of his life and family.

The tragic story of Zef Gjeloshaj and his family in Tuz

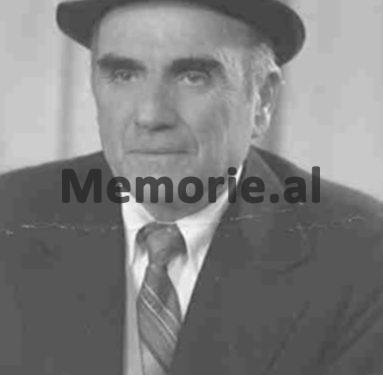

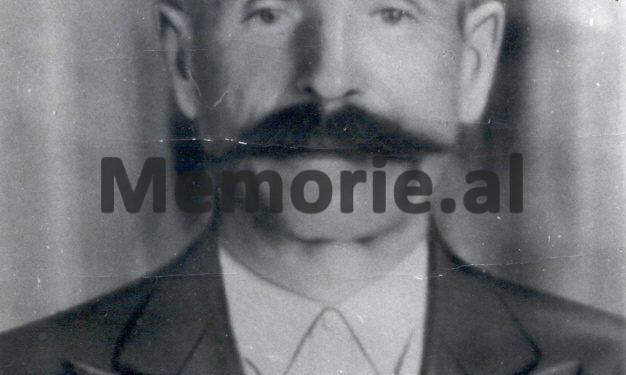

Zef Dod Gjeloshaj was born in 1931 in Triesh, Montenegro, in one of the most famous families of those areas with ethnic Albanian population. His father, Dodë Smajli, was one of the most listened to men in all the Albanians of that province, inheriting the command of the first of the country, which had been in several generations by the men of that tribe. During the Second World War, the Gjeloshaj family maintained a neutral stance by helping both Marshal Tito’s communist forces and Enver Hoxha’s partisans. In addition, Dodë Smajli’s house in Triesh was turned into a partisan hospital for Serbo-Montenegrin and Albanian forces operating in the province. By the end of the war, the Gjeloshaj family had no problems with Tito’s communist regime, and two of Doda’s sons were mobilized as soldiers in the Yugoslav Army. But their clash took place in 1946, when Doda’s son, Nikola, who was serving in Belgrade, killed a Serbian officer, and he escaped the death penalty after his father, Doda, met Marshal Tito. After being released from Goli-Otok prison, Nikola did not live long and died from the tortures that were done to him there. In 1950, Dodë Smajli himself was killed in an attempt by Serb-Montenegrin forces to surround his house after he refused to surrender a Serb major wanted by the Belgrade regime. After Doda’s murder, during that siege, his son, Martini, was also wounded, while his other son, Noshi, who was serving as a soldier in Kotor, was also imprisoned. Based on this situation where the Gjeloshaj family happened, the other son, Zefi, was forced to flee Yugoslavia and came to Albania. But he “fell from the rain to the hail”, as an even more tragic fate awaited him in his homeland. After being sent on a mission to Yugoslavia, Zef Gjeloshaj was accused of being an enemy of the people and imprisoned and interned for several years in his homeland, going through a long ordeal of suffering and vicissitudes. Although in 1984 the Supreme Court granted his innocence, suffering and lost youth to the prisons of the communist regime, no one could return it.

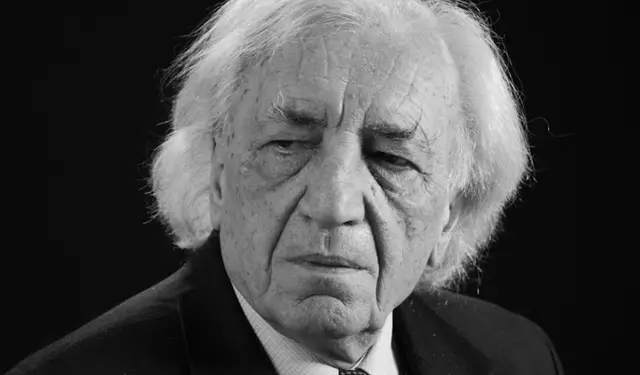

The great writer, Dritëro Agolli: “Voice of memory” by Zef Gjeloshaj, a book that makes us think!

The life and tragic story of Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, which is masterfully reflected by him in the book “Voice of Memory”, had prompted the prominent writer, Dritëro Agolli to make the preface, where he says, among other things: “Everyone is a story in itself, a story of work and war, friendship and enmity, love and hate. These are lived events, they are life and living experiences that people do not keep to themselves, but tell to each other, in the village, in the city, at home, in the cafe and everywhere. The most precious of these stories are spread by word of mouth and heard by a wide circle of people. However, when they are not written, they fade and disappear with the death of those who have told them and those who have heard them. It is therefore said that the past remains however it is written. Even the water does not drown the written thing. Nor does fire burn it. Zef Dod Gjeloshaj has the good fortune to tell and write the events of his life and for others they remain unforgettable. A man with great life experience and very complex, a man who has merged experience with culture and from this fusion has gained wisdom. This man named Zef Dod Gjeloshaj gives us a rare book with memories from his life in relation to the lives of other friends and opponents of truth and falsehood, and above all, of patriotism and ostensibility. In this book of memoirs, he recalls his vicissitudes when he was very young towards the path of truth, as in his youth he equated the ideal with the homeland and he called this true. This conception of truth then cost them dearly. As he writes in his memoirs, he escapes from the Albanian territories of Montenegro, comes to Albania with longing, makes him an activist of the Comintern, an international organization led by the Party of the Soviet Union for the triumph of socialism in the world. With this mission, the young Zef is sent back to Yugoslavia to gather information that would serve to overthrow Tito and his regime. Do not forget that we are in 1951, when Albania had two or three years that had broken with Tito’s Yugoslavia, like the whole Socialist Camp, when Zef Dod Gjeloshaj was a twenty-year-old boy, like me, but he in the Comintern, I am still in high school in Gjirokastra. This Zefi is strong. But I do not intend to repeat in this note what is in the book of Zef Dod Gjeloshaj. I want to confirm that opinion, which I mentioned a little while ago, in our youth we based the ideal with the homeland. So young Zef thought that his activity in the Comintern was a patriotic work, as I thought. But I want to say that Zefi for these historical, or ideological notions, has been quite clever, for this let us quote a paragraph from his book, which talks about a meeting of Comintern activists with Cuvahin, the Soviet ambassador and Mehmet Shehu, at the end of 1951: “As for my black, I, the youngest in age, addressed a question to General Cuvahin. Comrade General Vishinski, a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, said at a meeting of the Comintern: “We will eradicate Titoism, but we will keep the Yugoslav federation.” If so, we Albanians from Ulcinj and Bar to the Vardar Valley, what will we gain? Without thinking at all, Cuvahini said: “This is what Comrade Stalin said.” Gjerogjiani shook his head in approval and Mehmet Shehu, irritated, as he was by nature, addressed me: “You have not yet been liberated from bourgeois nationalism. “You did not know what age we were in.” “I was worried, but not enough to think that those questions would cost me dearly in the fate of my life.” Zef Dod Gjeloshaj masterfully in his book gives these ambushes in the course of the story, ambushes that try to hinder the lake of love for the homeland. However, for the homeland you grieve, but you do not get angry. Zefi, as I judge it, thought in the time of disappointments, that the state is not always homeland. In the story of his life, Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, without falling into artificial literature, possesses the mastery of the trap to catch the reader, possesses what I would call the heart of the clock not to be left untouched, in a word that the event goes ahead, for the reader to become curious and say; what will happen next? In the first pages of the book, when he tells about his life as a student in the gymnasium of Peja, he says that he was followed by the people of the Yugoslav security, those of the UDB. Zef Gjeloshaj writes about this: “The blows against me started in Gjakova. I was concluding that I did not know much. Poor Socrates, why didn’t he leave me a ration of poison from the one he drank when he was sentenced to death for blasphemy by the Tirana Tirana group? And further happened many events, many vicissitudes, many despairs and joys. With a strange composure, he gives the tragic events, like that of the poisoning in Tirana Prison, but it is the composure of the revolt, which calls the other prisoners; beware that I was poisoned! The book of Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, this man who comes from a large noble and patriotic family, shows the birth, formation and maturity of a man. This book is not written in the form of a boring chronology, but of a strange movement within the chronology. The author, for example, even when he sets the event in the 50s of the last centuries, has an intervention for our days, even when he tells about a place where he went, he reminds us of the history of this country. With his book, Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, he is known for a wide literary, philosophical and political culture. This makes him narrate in the book with special wisdom and with admiring human feeling even the most tragic events of his life. Zef Dod Gjeloshaj, with his experience and culture knows that, except the flag eagle, all other eagles make cries …! (Dritëro Agolli) 13 December 2006.

Gjeloshaj Memories: Meeting with Marshal Tito

Around July 10, 1950, Tito and Jovanka and his escort came to visit the general headquarters of the Belgrade-Zagreb highway. All the staff and staff came out and welcomed him. He greeted us and shook hands with us all. Rather he spoke with a lovely secretary, Mica Antiq, from Opatija beach. Jovanka looked at him with a wild look. Tito asked Mica in detail about her hometown, because Tito knew those places, because in the village of Kumrovac in Zagreb, he was born and raised, not to mention the picturesque places and beaches he cared about. When he addressed us, he said in a short speech: “Friends and comrades. It is in your honor that you are successfully building the Belgrade-Zagreb highway, which is our main objective of this 5-year plan. This is the best answer our people give to the accusations and slanders of the Cominform and the Kremlin mustache. Recently, Stalin poisoned Gjergj Dimitrov, but in our country, he encountered a nail saw. Cominform and the entire Soviet bloc call this highway you are building with golden hands a giant airport for Anglo-American aircraft. Your arms are happy and I wish you good work “. Tito with his appearance to give the impression of a strict but determined leader. When he pretended to be laughing, he pulled out his beautiful teeth, including the gold one. As a kapadaiu, in the marshal’s uniform, he took the commander and his deputy with him and locked himself in Ante Josipovic’s office. We dispersed to our offices. He stayed with the commander for a long time. When he left, the escort did not allow a second meeting with him. Accompanied by the commander, they apparently went to a tourist spot. I, who had the fly under my hat, during Tito’s visit tried to maintain a normal posture, applauding with my friends. During this time, I noticed that throughout the meeting, I was not assigned a staff called Rajko Kopricka. He clung to me and pretended to caress me, putting his hands close to my pockets. This was a nice check by Rajko, who was also the director of staff. I later thought of this imposing and energetic Tito, who, together with India’s Jawarlal Nehru, Indonesia’s Sukarno, and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, led the “Third World, the Uninvolved World,” told me by Radule Styenski, a revolutionary writer from Montenegrin pepper, but who had long lived in the Soviet Union, as its citizen.

How did Tito come to be at the helm of the Yugoslav Communist Party?

Radule, among other things, told me: “Tito as a non-commissioned officer in the Austro-Hungarian army and as a partisan of the Bolshevik revolution, since the First World War, remained in the Soviet Union. We in Moscow lived the life of the Party together, he was like a silent zombie, where he uttered the words as if he had money, one day, to the surprise of the entire Yugoslav communist organization in Moscow, on the recommendation of the KGB, and by decision of the Comintern, our secretary was elected, and from then on, he began to open his mouth. He disappeared for weeks and months and, to justify his absence, was said to be traveling through Europe, charged with duties by the Comintern. He even went as far as Latin America. This sudden appointment came after Stalin summoned to Moscow one by one the two general secretaries of the Yugoslav Communist Party, which at the time was one of the strongest in Europe. In addition to Yugoslavia, Tito was given a “license” to oversee the movement and organization of the Balkan communists. He left his first wife and children in Russia. His son, Zharko, even became a Red Army officer and lost his arm at the Battle of Stalingrad. Tito was educated in Moscow, at the Bolshevik Red School. So, he, from a mechanic, became a leader. After the 1950s, when the Belgrade-Moscow agitation reached its climax, the leader of the Communists and the Spanish Revolution, Dolorez Ibarruri, wrote: “The current Tito is not the real Tito, he was taken prisoner in the Spanish War and Hitler’s Gestapo “With a German Gestapo major.” Montenegro’s chief and most authoritative man, World War II hero, friend of Dodë Gjeloshaj, and, as you will read (whose nephew, Belgrade Aviation Commander Radomir Mirasevi)), was killed by the UDB together with Doda. Speaking of Tito, General okaoka Mirasevi, said: “In 1948, I took a stand against Tito, siding with the Informbureau and Stalin. Tito called me several times in his office, convincing me of the “right path”, proposing me to change my mind. I told Tito: “Put on your hats and go to Moscow and convince Stalin of the justice of your path. “Then I will be with you.” Tito laughed sarcastically and said, “Should I go to the butcher like a goat? But did not Stalin treacherously eliminate the two general secretaries of the Yugoslav Communist Party, Gorkic and Petko Miletic? I remember one-night Stalin, at the meeting of the Comintern in Moscow, severely criticized a friend of ours, a Comintern activist who operated in Argentina. He criticized him in the evening and was killed the next morning. “Stalin, as a bloodthirsty man, has long arms for crime.” To the elderly general, disobedience to Tito cost him dearly, exiling him to the secret camp of Goli Otoku, who for the horrors and tortures, and especially the trampling of human dignity, passed them on to racist camps. If Tito is credited with breaking Stalin’s nose, he opened up and liberalized Yugoslavia, made it so rich that the world called it “Little America.” He quenched his thirst for Serb-dominated rule by creating two autonomous provinces: North Vojvodina and South Kosovo.

Preparations to escape to Albania

Otoku’s goal for Tito will remain a stain of shame for his long reign. Today, General okooko Mirasevi ka has the statue (lapidary), the most magnificent of Montenegro in the center of the capital, Podgorica. Gjoko is of Albanian blood, from the womb of the Margilaj of Lulnikëve of Tries, but was born in the village of Dalan near Podgorica. I can say that General Gjoko has been and remains the most indisputable authority of Montenegro. The Belgrade-Zagreb highway, according to Tito’s order, has been made straight without any turns, regardless of which objects it would violate. When I crossed that street, I remembered the prison of Mitrovica e Sremit, where many Albanians arrested in Kosovo were locked up in this death prison from where, as it was said, no prisoner came out alive. I remember my brother, Nikola, who was tortured to death in this prison. The days of July 1950 were passing. The ground beneath my feet was burning. I received a service order from the headquarters for the Vinkovac sector. As soon as I put the letter in my pocket, I cut the train ticket, not to Vinkovac, but to the Shamac-Sarajevo-Titograd line. He left on July 19. The train flew over the Srem plains. This speed slowed down a lot as I was crossing the endless valleys and mountains of Bosnia. In the town of Zenica, a major steel industrial center, the town was not visible from the smoke of numerous metal smelting furnaces. I knew that in this city of smoke, the Yugoslav kings had set up a prison with a heavy regime. Of course, this prison was also used by Aleksandar Rankovi… I remember the Montenegrin Jole Markovi ((later president of the Yugoslav emigration to Albania), was held in this prison for 12 years in a row handcuffed by the Kingdom of Belgrade. The train rolled through countless tunnels through the high mountains. It seemed to me that the train was not going at all. If I had the opportunity to push it too, together with two locomotives that had to increase its speed – to reach Titograd, the Albanian border, as soon as possible. With all the impatience that did not let me close my eyes, I wanted to intercept the sites of the Illyrian mass graves in the area of Bosnia. On the evening of July 19, I arrived in Sarajevo, this beautiful and very pleasant city. I had to wait a few hours on the next train. I went out for a walk in the city. I drank a lot of water. And where should I not drink the water of Sarajevo? In no city in the world have I drunk better water. Sarajevo between the mountains is full of shops, where you can see jewelry, cosmetics, like in no other city in the Balkans. It was not the fault of the Shkodra merchants who coveted the Sarajevo market. Let us not forget that Sarajevo is the place where Prince Ferdinand was assassinated, which became the cause for the start of the First World War. I boarded the train at night. I reached the town on the slopes of Mount Mostar. I thought of my mother’s cousins, the Ivanaj brothers (Mirash and Martin), where they had graduated with honors with excellent results, despite the difficult economic conditions, being forced to work in their spare time as a breadwinner. mouth. The train continued its work. A veteran fellow woke me up from my nap, saying: “Look, boy, there on the left is the Stutjeska valley. The largest partisan battle in the world took place there. Surrounded by the Nazis, 6,000 partisans were killed, 6,000 sons of mothers in the flowers of youth. My nephew, the commander of the division of these heroes, “People’s Hero”, Savo Kovacevic, was also killed there. Marshal Tito was wounded in this battle. “His loyal dog was also killed there, treating the wounds with his tongue”, the veteran concluded with tears in his eyes. After 1992, I remembered Bosnia and Sarajevo as beautiful brides, where they committed the biggest massacres for Europe, after the Second World War, the sadist and bloodthirsty of Kosovo, Slobodan Milosevic, (rabid dog). He destroyed with heavy artillery Sarajevo flowers, killed women and children with his deputies; Mladic and Karadzic carried out the most unprecedented massacre in Srebrenica – where they brutally killed tens of thousands of innocent Bosnian Serb men, women and children, simply because they were of the Muslim faith. The French philosopher Blaise Pascal says: “People never do evil so completely and happily as when they do it for religious beliefs.”

July 20, 1950, in Titograd

On the morning of July 20, 1950, I landed in Titograd, in the old town of Diocletian, founded by the Roman emperor Diocletian (who the locals say is of Illyrian descent from the village of Dinosh). The geographer Alexander Ptolemy also talks about Diocletian. Before getting off the train I was looking at the beautiful Titograd, completely rebuilt by the hands of the German prisoners of war, a town lying on the plain of Qemo crossed by Montenegro’s largest river, the Moraca, and by the river little Ribnica, on whose bridge in the center of the city, the hero of Kosovo and Vlora, Isa Boletini, was treacherously killed 90 years ago. As I was passing through the middle of the city, I felt as if all the people had their eyes on me and were watching me. The truth was that no one in Titograd knew me. On the way I met a girl, Lena, a childhood friend. Since she was going to Tuz, where she had her house, I asked her to call Isuf Qetkaj (a teacher in Tuz) to come here and meet me at the Mark Milli restaurant, where I took refuge. In less than an hour, Isufi did. He told me about the situation, about the wounds received and the bones broken by the Yugoslav Security (UDB). The faithful were remaining faithful and could not have happened otherwise. Isuf Qetkaj, son of a son, son of the mayor of Ledina, and grandson of the first door of Hoti – Delimetaj. Minute work we made the plan – the day and hour of the emergency escape. I would go out to the mountain of Koshtica and he to his mountain, in the Ice of Ledina. At noon on July 22, Isufi came to my yard, we ate boiled cheese and we saw that the border patrol was with the family of Nik Gjoka and Pashke Loshe, who had eaten and drank it. We made sure our border area was free. Care had to be taken with landmines. Without greeting anyone we left. My older sister, Palina, who had come to her people for the summer, with the special natural ingenuity that characterized her, sniffed the problem, escorted us to the door and said: “You are going out for a walk, you good priests”. With the youthful speed that characterized us, we crossed the mountain of Iballa and entered the slopes of Slap, to reach the beautiful waterfall of Peruqia of Selca of Kelmendi.

Crossing the border to Albania

When we crossed the border we breathed freely, the air of Albania seemed sweeter to us. Not only beeches and pines, but every Albanian thorn and bush looked to us like the hanging gardens of Babylon. “We quickly crossed the border, Isuf.” “Yes,” he said, “people say: Light legs, white face.” I was reminded of the words of Russian General Suvorov as he crossed the Carpathian Mountains with his army. To get to the battle as quickly as possible, he said: “At the feet of my soldiers, our victory depends.” Speaking of Gjergj Kastriot’s skill and speed, General James Wolf, the Hero of Quebec, Canada, said: “Skanderbeg surpasses all ancient and modern heroes.” We arrived at the local government offices in Selce. There we found the secretary of the Municipality, Vat Gjeloshi, a handsome and very noble middle-aged man. We insisted on surrendering to the police. We went to the post office, where we were warmly received. They were amazed at how we had crossed the border on a sunny day, without being dictated to by either side. The next morning, accompanied by a police officer, we left on foot for Shkodra. We got so tired that I could call it the “Road of Trouble”. The Kelmendi valley was not exhausted, let alone Hoti. In Tamara I wanted to meet my mother’s cousin, Katrina Mara, but the companion told us we did not have time. Later I met her son, Zef Bujaj, in the “universities” of building the palaces “Agimi” in Tirana “. From Selca to Rrapsh i Hotit, we arrived at noon. The escort took us to the Defense Department for lunch. I insisted, telling my companion that I definitely wanted to meet my aunt, married to Mark Elez Shabaj, one of the most heard houses of Rrapsha and Malësia. I went to my aunt but unfortunately, I did not find her there, because they had gone to the mountains. There I found her brother-in-law, the hero of the Deçiq War and the battles of Sukave and Mokset, Dedë Elez Shabaj. In the wars for the protection of the Albanian territorial integrity, this fighter had lost his leg and received many wounds on his body. In conversation with me, he harshly criticized the ruling regime that existed in Albania. His words touched my soul, because I knew Albania as the most ideal country in the world. Marashi, Aunt Zoja’s eldest son, did not speak at all. We slept with a villager in Budisht. The next day, we left for Koplik, Shkodra district. The companion hardly slept at all. He was vigilant because he had responsibilities for our lives. On the way, we met not only villagers with rifles in their arms, but also border guards and police. The policemen and soldiers were in torn clothes and with patches. This shocked us a lot. Isufi was openly showing pessimism. Exhausted, we finally got off at Koplik, where we got into random cars. The Shkodra Branch of Internal Affairs welcomed us well, but the Intelligence specialists asked for information from various sources, so much so that they forced me to say to the leaders: “We do not come from the headquarters of Goshnjak and Rankovic, but we come from the school benches.” Zaim Myftari from Belishova and Irakli Kocani from the villages of Vlora, understood us. We slept in hotels and ate in restaurants. Maybe formally, but in fact they told us: “Do you want me to stay in Shkodra?” Without thinking at all, we replied: “No, take us to our immigrant friends.” After a while they fulfilled our wish. And where would we go? They took us to the camp full of mud and dust of Llakatund of Vlora. We were so upset that we said to each other, “Is this the paradise we imagined?” Luckily, we did not stay long in the camp. Only a few months. Later I was transferred to the education section of Lushnja, and Isuf, who did not want to work as a teacher, was taken to Fier./Memorie.al