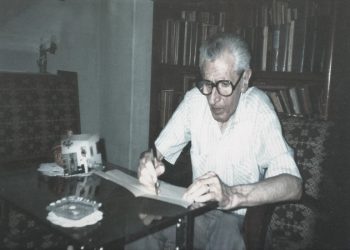

Memorie.al / Rousseau rightly said: “The scale of a book’s value depends not only on how much it moves you, but also on how much it makes you think!” The novel “Kojrillat” (Cranes) by writer Fatmir Terziu, by excellently fulfilling both these components, undoubtedly remains a creation of great value. The writer Fatmir Terziu himself entered the pantheon of our literature with dignity: without noise or fanfare, quite naturally, without seeking glory, even bestowing it upon others, encouraging anyone who dares to embark on the beautiful path of art, telling the world that Albanians not only do not lack culture, but, as someone’s saying mentioned somewhere in the book suggests: they are the most intelligent people in Europe.

Thus, above all, Fatmir Terziu is, in the Sartrean sense, a conscious being whom he simultaneously views and uses as a witness and a judge. Therefore, just like Euhemerus of the Hellenistic period, around the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 3rd century B.C., with his novel Sacred History, where he claimed to have found an inscription on the island of Panchaea that explained the origin of the Greek gods, he too sets out in search of “our holy grail,” of some mysterious letters that, within their enigma, clarify many ambiguities from the history of Albania, a history filled with intrigues, betrayals, ambitions, injustices, and deceit.

Those letters are possessed by a beauty named Zeinep Vlora, the wife of Xhemil Vlora, who, for her part, quite well fulfills Albert Camus’s credo that; “Absurdity reigns, love saves you!” And just as in The Myth of Sisyphus, Terziu himself seeks to become the master of the absurd, but without lacking purpose. The purpose of his Sisyphean toil is a consequence of civic responsibility and patriotism.

And if he does not succeed, after all that effort in archives and newspaper pages, at least he manages, through his love, and also that of the Albanian woman who, with her suicide, became the focus of media, political, and diplomatic attention in the 1930s, to set people’s minds in motion, to unite their efforts and forces to successfully tackle a not insignificant national problem.

The ways to address such issues are varied. But Fatmir does not put on the historian’s cloak; based on his talent and experience, and especially after his previous novels, Grykësit (The Greedy) and Bunari (The Well), he remains within the realm of literature. Didn’t Fyodor Dostoevsky himself act similarly, of whom Albert Camus also said: “…very soon, as I began to feel and become aware of the drama of our era, I fell in love with that writer, for the incomparable ability he shows in highlighting and presenting our historical destiny!” And hasn’t our historical destiny been filled with mysteries and enigmas? With unknowns that were never answered.

It is enough to recall the last century, which Fatmir Terziu also deals with in this novel. Metaphorically, only the cranes know them. In their peaceful and perpetual flights, in calm and turbulent skies, from one state to another, they have seen and can testify. For they have heard the conspiracies hatched behind the scenes or at international conferences, by the powerful, to the detriment of our interests.

But go ahead and find the language to understand them. We have also had intrigues and betrayals among ourselves. And naturally, they have influenced our entire historical destiny. Thus, it is understood that the theme encountered in this book is broad, if not endless. But the writer has focused on symbolism, on opinions, articles, and a few characters.

He does not waste time describing their portraits, their characters, or other features. Mostly, they move like shadows, constantly under the gaze of the cranes. The author says: “The hero fell! The victim – a person left this world. She left her unread last will to the cranes. And perhaps they have this will. Perhaps. Yes, yes, the cranes have read Zeinep’s will and fate!”

You also find in the book what the author calls; I wet even the stones that speak with their muteness, because; “even when they are uprooted from their bed, they still have the same weight, if not more” (but surprisingly, both the watery and the rocky aspects of this space become one in such cases), and the English investigator, and Lutfi Çela, and… the author himself, now Granit Jetoni.

The chronology itself seems to be lost. But no matter how much it is lost, the concern remains the same. At this point, there is no deviation. Zeinep, like the cranes, seeks to migrate, but her path is full of obstacles, as she seems to want to confirm Conan Doyle’s observation that; “Women naturally like mysteries and enjoy being surrounded by a network of secrets!”

In the delicate struggle to find herself, she truly appears defeated, but nonetheless earns the reader’s respect. A veil of mist surrounds her. Her beauty itself resembles the paintings of the French Impressionists of the years 1867-1880, that is, of the France where she wanted to go, even if only as a nurse. She says nothing, as she does not converse with anyone, and yet she remains the main character.

More than for her young life, one feels sorry for the unknown manner of her death. Why did this have to happen to this woman who, like a true princess, made the environment sparkle, and who believed that the independence of the homeland was meaningless without her independence as a woman? Who was interested in her no longer living? Were the murderers Albanian or foreign?

And what about that man, whose corpse was found in the Thames a little later…? Could these, or perhaps more than these, be connected to our journey concocted along the moldy dead ends of history, as the writer himself expresses? The time of Albanian communism does not escape the antipathy of this author, who has long since displayed his democratic convictions.

Here, by playing with words, he speaks the great truth in the dialogue of a secondary character: “Once the elders thought well for a bad day…! Now the bad thing is the everyday…”! Naturally, this would happen, since someone previously stated that we were silent, but they did not leave us in peace even in our silence. We lived in a country where “…man himself attacks man on his path of life”!

In the composition of this work, Fatmir Terziu has operated with different figures, colors, places, and events. They, and the characters that fluctuate from deputies to very simple people, seem to have no correlation whatsoever. But this is not the case. All are well thought out, so much so that you feel like you are facing a detective novel.

But no; this writer has labored greatly until he finished this book. He has left no flaw on his part. If he has not managed to give us exhaustive answers about the secret carried by the undiscovered letters of the graceful madam Zeinep Vlora, it is by no means his fault. Besides, can anyone come forward today and convince us that Odysseus was the son of Laertes or of Sisyphus himself, who fell in love with his mother, Anticleia, who also died of grief from the long absence of her son.

What is known is that Khalil Gibran said that; “One of the most beautiful things in life is finding someone who can understand you, without needing to give many explanations!” Fatmir Terziu, the talented and knowledgeable writer, and the big-hearted man, but also the brilliant patriot, who like that heavy stone even when far away, from London where he lives and works, should be sure that he will find his reader. A reader who not only understands him but also looks forward to other books from him with pleasure. Memorie.al