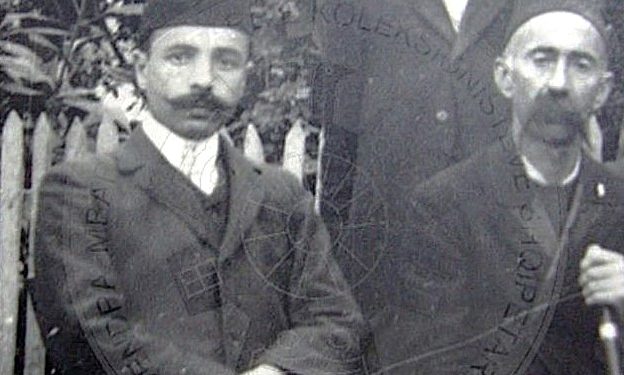

Memorie.al / Selahudin Blloshmi were the son of the renowned patriot Hajdar Blloshmi (1860-1936). Hajdar had been a French language professor at ‘Robert College’ in Istanbul, but due to his patriotic activities, he was expelled from Istanbul and returned to Albania, where he worked as a French teacher in several cities, such as Pogradec, Elbasan, Durrës, and Tiranë. In 1909, with the opening of the ‘Normal School’ of Elbasan, he was one of its first teachers, alongside Luigj Gurakuqi, Aleksandër Xhuvani, Simon Shuteriqi, Ibrahim Dalliu, etc.

In November 1912, representatives of the villages of the Starova (Pogradec), Bërzeshta, Qukësi Kaza (district), etc., sent a telegram to Hajdar Blloshmi, informing him that they had chosen him as their representative to the Assembly of Vlora, which would proclaim Albania an independent state (Lef Nosi: Historical Documents (1912-1918), 2007, page 79).

However, Hajdar Blloshmi did not arrive on November 28, because the Serbian army had occupied almost all the cities of Central Albania, including Durrës, causing the native of Bërzeshtë to lose the historic chance to be a signatory of the Declaration of Independence. On December 2, 1912, he arrived in Vlora to continue the proceedings of the Grand Assembly until its conclusion. He was a deputy in the first Albanian Parliament, from 1922 until his death in 1936.

Selahudin was born on March 21, 1892, in the village of Bërzeshtë in Librazhd. He completed elementary school and military high school (Cadet School) in 1911 in Istanbul. In 1915, he published a book of patriotic poems in Sofia, titled “Zan’ i Fronit, Mbretit e Shqiptarëve” (Voice of the Throne, King and Albanians) (Sofia 1915), dedicated to Prince Wied (A. Bishqemi: “Elbasani” Newspaper, April 1999). During World War I, he served as a captain in the Franco-Albanian army of the Korça Republic. In November 1917, he was appointed as a delegate of the Commission to negotiate with the Greek military side for the determination of the state borders between the two states.

In 1919, he participated in the Paris Peace Conference as a delegate of Korça, to protect Albanian national interests and the integrity of Albania’s state borders (M. Grameno: “Gazeta e Korçës”, No. 11, dated December 17, 1929; S. Vllamasi: Cited work, page 117). In 1921, he was sent to France for two years to pursue advanced military studies at the French Military Academy of Saint-Cyr in Paris. When he returned to his homeland, he served in the Court of King Zog I, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

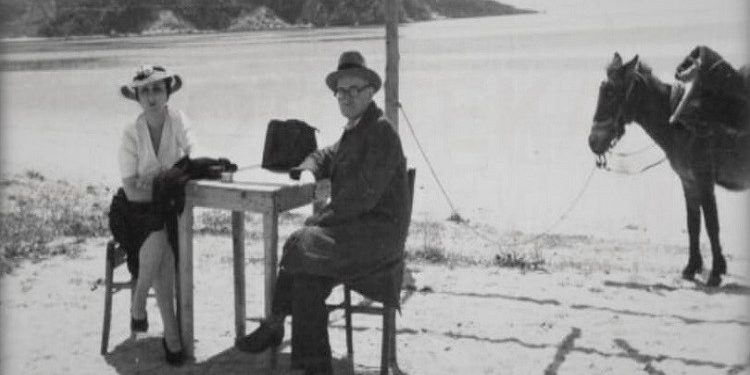

Selaudin Blloshmi was a deputy for the prefecture of Elbasan in the Albanian Parliament until 1926. He married Sara, the niece of Ismail Qemali, an icon of Albanian beauty and one of the most emancipated women of the time. During the years 1926-1928, Selahudin served as Plenipotentiary Minister (Ambassador) of Albania in Bucharest, Romania. In the spring of 1928, he returned to his homeland and was appointed Prefect of Tirana. He died in 1929 from a heart attack. Selahudin Blloshmi was decorated by the French president with the order of “Chevalier of the Legion of Honor” (Knight of the Legion of Honour).

Before World War II, the figure of Selahudin Blloshmi was valued for his outstanding contribution to the national cause. During the war, his brothers were aligned with the nationalist forces. Selahudin’s brother, Haki Blloshmi, was the commander of the nationalist ‘Balli Kombëtar’ (National Front) band, which was the political opponent of the PKSh (Communist Party of Albania). The two Blloshmi brothers, Haki and Shefqet, were captured by the partisans of Mehmet Shehu’s First Assault Brigade and executed by firing squad.

Hajdar Blloshmi’s entire family was persecuted by the communist regime. Selahudin’s figure was tarnished with monstrous slanders and insults. Even after the fall of communism, Selahudin Blloshmi was more often mentioned as Sara Blloshmi’s husband than as an important figure with extraordinary contributions to the national cause, such as the territorial defense of Albania and the saving of the city of Korça from annexation by Greece.

Selahudin Hajdar Blloshmi deserves a monument to be erected in the center of the city of Korça, just as the monument of American President Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was erected in one of the centers of the city of Tirana.

THE ACTIVITY OF SELAHUDIN BLLOSHMI IN THE NATIONAL CAUSE

At the end of World War I, the Allied armies had deployed their troops across almost all of Albania. Thus, Vlora with its entire coast, Tepelena, Gjirokastra, etc., were occupied by Italy. In the autumn of 1916, the Italians had attempted to occupy Korça as well, but they were opposed by Serbia and Greece, which sought the annexation of Korça for itself. After much discussion, it was decided that Korça and its districts would be occupied by French troops, who were considered uninterested in territorial issues in Albania.

Following their deployment, the French military troops allowed the creation of a regional autonomous province, called the “Autonomous Province of Korça”, which was led by a Council of 14 members, half Christian and half Muslim. The maintenance of order was entrusted to an Albanian gendarmerie, under the command of the well-known patriot Themistokli Gërmenji. The Autonomous Province of Korça printed its own coins, postage stamps (where it was referred to as a “Republic”), etc. The Albanian language was recognized as the official language, while the flag of the autonomous province would be the flag with the double-headed eagle and the tricolor stripes of the French flag.

During the First World War (October 1916), Greek Prime Minister Venizelos had tried to introduce his army troops into the city of Korça, which was still occupied by the French army, but General Sarrail had prevented the Greek army, ordering their withdrawal from Korça. Over time, especially after the end of World War I, Greek aims for the annexation of Korça increasingly dominated its politics. This continuous objective of theirs also influenced a pro-Greek stance in French diplomacy.

“At the Peace Conference,” writes historian Pëllumb Xhufi, “France’s Foreign Minister, S. Pichon, tried to satisfy Greek ambitions by inventing unsustainable strategic arguments. He admitted that from a historical, ethnic, and linguistic point of view, Korça was undoubtedly Albanian. But in the conditions of an Italian protectorate over Albania, the interest required that this city and its surroundings be united with Greece.” (P. Xhufi: “Dita” Newspaper, August 20, 2020).

French diplomacy did not approve of the regime established in Korça, in which the French army co-governed with the Albanians. “On June 14, 1919,” writes Xhufi, “Minister Pichon complained to the Prime Minister and the Minister of War about the behavior of the French military authorities of occupation in Korça, where, according to him, they; ‘are doing everything possible to emphasize the Albanian character of this province and are hostile towards the Greeks… we have no interest in seeing Korça become Italian under an Albanian label, so we must not support the Albanization of this province’!” (P. Xhufi, ibid.).

On July 7, 1919, General de Bourgon, commander of the French troops in Macedonia, reported that the situation should be changed in favor of the Greeks, that strong pressure should be exerted in favor of Greece, that only Greek schools should be allowed and the teaching of Albanian should be banned, every Albanian symbol should be eliminated (as had been done in March with the prohibition of the Albanian flag), and the Albanian gendarmerie should be disbanded, replacing it with the Greek gendarmerie.

“On July 24,” writes P. Xhufi, “the Foreign Minister of Athens, Politis, asked his French counterpart that the ‘regime that existed there before the arrival of the French army’ be established in Korça, meaning that the Greek occupying forces should be placed there, and to achieve this he proposed as an initial phase the transfer of those French officers ‘responsible’ for favoring Albanian nationalism.

The Greek request found the support of the French government, and on August 10, the French Ministry of War informed Commander de Bourgon that within 15 days the province of Korça should be handed over to the Greek authorities. The news had to be kept ‘in the absolute secret’ (tenir la nouvelle absolument secrète), so as not to disturb the population of the Kaza and not cause its reaction. (P. Xhufi, ibid.).

The French troops ordered the attack and destruction of the Albanian komite (guerrilla) bands, which would attempt to oppose or prevent the transfer of the city of Korça into Greek hands. They arrested and killed the patriot Themistokli Gërmenji, accusing him of treason, but in fact, they feared he would oppose the entry of Greek troops into Korça.

The French instructed the Greek troops to be careful when entering Korça, to enter without triumphalism, without demonstrations, and without expressions of joy, as any clash with the Albanians would complicate the successful development of their operation. On April 26, 1920, the news spread in the city of Korça that in the city of Florina, the Greek army was preparing to occupy Korça after the departure of the French. This news had alarmed the citizens of Korça, who had gathered by the thousands, armed to defend their city.

To prevent the occupation of Korça, a commission was formed, consisting of; Jorgi Thashi, Nikolla Zoi, Pandeli Cale, Qani Dishnica, and Captain Selahudin Blloshmi, who momentarily averted the danger of occupation (E. Vlora, “Kujtime 1883-1925” (Memoirs 1883-1925), Tirana 2005, pages 456-458). Fortunately, this Greek plot to hand over the city of Korça to Greece failed before the annexation was announced.

WHAT HAD HAPPENED?

How did the events change, and who ordered the stopping of the Greek army from entering Korça? “During the proceedings of the Paris Peace Conference,” writes Sejfi Vllamasi in his memoirs: “Venizelos, who was one of Greece’s most distinguished diplomats, had managed to secretly obtain the consent of Clemenceau and Lloyd George, behind Willson’s back, to occupy Korça…

The Albanian delegation knew nothing at all about what was happening in Korça. Accidentally, a telegram from the Deputy Chief of Police of Korça, Oliver, sent to his superior in Paris, Captain Vot, woke up the Albanian delegation from its slumber. Olivet telegraphed that they had received an order to leave Korça and to hand over the city to the Greeks on that occasion!” (S. Vllamasi: “Ballafaqime politike në Shqipëri” (Political Confrontations in Albania), second edition, Tirana 2000, pages 208-209).

HOW DID THIS TELEGRAM FALL INTO SELAHUDIN BLLOSHMI’S HANDS?

The protagonist of the event was a young Albanian officer with the rank of Captain, named Selaudin Blloshmi from the village of Bërzeshtë in Librazhd, who was a member of the Albanian delegation and simultaneously the commander of the Albanian army of Korça. “This telegram,” writes S. Vllamasi, “was addressed to the Military Club, which Selahudin Blloshmi often visited, and the telegram accidentally fell into his hands. Alarmed, he notified Pandeli Evangjeli and his colleagues.

Without wasting time, they requested an audience with President Willson, informed him of the matter, and begged him to stop the Greek occupation of Korça.” Willson, who knew nothing of his colleagues’ intrigues, strongly protested and forced his two colleagues to order Venizelos to abandon this adventure! (S. Vllamasi, page 209). On May 20, 1920, the French army withdrew, and from that date, writes Vllamasi, “the union of Korça with Tirana took a formal, decisive shape” (Vllamasi, page 209).

This important victory for the Albanians was dedicated to Captain Selahudin Blloshmi. “It was one of the most critical times for Korça,” the patriot Mihal Grameno would write. “As soon as the French army left, Korça united with Tirana: and complete peace reigned under the protection of the brave Selahudin.” (M. Grameno: “Gazeta e Korçës”, No. 11 (941), dated December 17, 1929). / Memorie.al