By Eugene Merlika

– LANGUAGE OF THE NATION –

Memorie.al/ Recently, a topic of great interest for the Albanian-speaking community, for today and for the future, has been discussed in various notebooks of the Albanian press, inside and outside the country. The written language and its concept of spelling have been discussed. Different opinions have been expressed, often contradictory, with strong polemical inclinations. The problem has been awakened from its lethargic sleep, several decades old, by the Prishtina newspaper “Java”. The start seems good to me and, perhaps, it reflects a certain re-examination, in the self-reprimanding direction, of the attitudes held by the intellectual and academic part of the society of those three Albanian worlds after the Spelling Congress held in Tirana in 1972.

The issue, to which many pages of the press have been devoted, is that of the unified literary language, the so-called “standard”, which is a set of morphological rules, mandatory to be applied in the official language and mainly in the written one. School, information tools, literature, state administration are the spheres in which the standard should find its full implementation. Until 1991, he was all-powerful in the borders of the Albanian State and had even occupied the educational and cultural institutions of the Albanian territories in the former Yugoslavia.

In itself, the phenomenon expressed a necessity of Albanian life, of its culture and institutions. A unified language is an indicator of the identity and vitality of a nation, it is the basis on which its culture and experience are built and passed on, it is the means of connecting the citizens of a generation and the generations themselves with each other.

Albanian is a language that is both ancient and new. Ancient, because it is the spoken language of a people who, historically, have lived in these lands since the dawn of European civilization, but who, unfortunately, have not left us anything written. The autochthonous language of the Illyrian communities, which were organized into states, sometimes powerful, and which faced or engaged with the great Powers of the time such as Macedonia or Rome, has not been passed down to us for millennia. It is a phenomenon bordering on the unbelievable that these populations, on whose lands some of the most famous centers of ancient Greco-Roman civilization were born and developed, that were not dissolved by any kind of foreign invaders, have not leave their tongue which must have been the most powerful weapon they used against this danger…!

To get to written Albanian, we have to go into the late Middle Ages, in various notes of travelers and crusaders who passed through Arbëri and stop at the Baptism Formula, to get to the first book. Gjon Buzuku’s “Meshari” was published in the middle of the sixteenth century, when Europe had many universities and its cultural renaissance heralded new times. Five hundred years of Ottoman occupation, without an education system in the local language, certainly had devastating consequences in that direction as well. It took the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, with the titanic efforts of a handful of patriots and scholars, for Albanian to emerge from “anonymity” and seek its place in the trunk of the Indo-European languages, as a separate, unrelated language. related to any of the major European language groups.

As a new language, in the sense of its immobility, which did not have a Dante or a Shakespeare at its foundation, it would be based on phonetic criteria, in the spoken language, to derive from it the rules that would determine the structure of her. But the language spoken varied from one province to another. The closed life, the lack of roads and means of communication, the patriarchal mentality and the immobility of the Ottoman state system meant that in five hundred years the relations between the different provinces, at the population level, were very few and, as a result, the spoken language was dialectal and there was no tendency to approach unity. The main dialects were: Gege north of Shkumbin and Toska south of it. In these dialects, which had their own subdivisions, the new Albanian literature and culture was born and took shape. They had their origins in the Renaissance, mainly in the Albanian colonies outside the country and among the Arbëreshes, but took their full form in independent Albania, from the beginning of the last century.

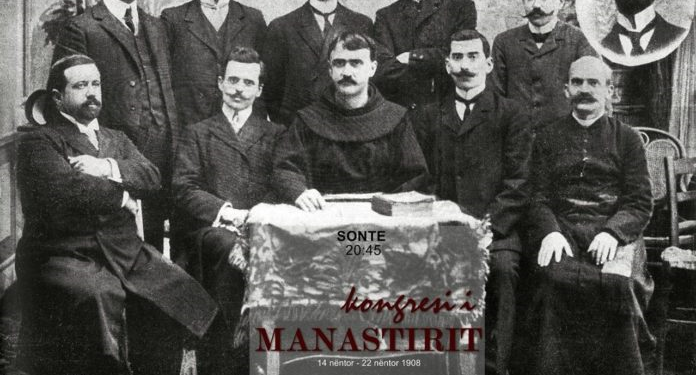

The birth of this culture emphasized the necessity of its presentation, i.e. of writing a common and accepted alphabet. The Congress of Bitola, in 1908, was unable to make a firm decision and left two alphabets in force: the one with Latin letters that was used in the north and the mixed one that was used more in the south. Time made its choice and the Latin alphabet remained the only alphabet of the Albanian language. The alphabet took its permanent form, but dialects continued to flourish and all were served by it.

The creation of the State and its institutions, the establishment of schools and the development of education, the spread of culture and literature in the entire Albanian space, brought forth as a first-hand task the embodiment of the national literary language. In the first decades of the last century, until the arrival of the communist regime, this task was entrusted to the personal research of the language learners rather than an institutional initiative in that direction. The awareness that the phenomenon required its necessary time to be achieved meant that there was no special impetus from the State. In 1940, the first Conference of Albanological studies was called in Tirana, in which there was a dominant place in the beating of opinions on this issue, but without taking firm decisions.

The overwhelming majority of the qualitative opinions of Albanian and foreign scholars coincided not with the predominance of a main dialect, Geghrish or Toskresh, in the national literary language, but in putting the sub-dialect of central Albania, more precisely Elbasan, at its base. The selection criterion of this subdialect was based on a number of reasons. He was seen as a connecting bridge between the Toskreshche and the Gehreshche, the Shkodranish or the two sides of the Drin and, in this view, more easily understood and digested by both the northern and southern populations. The competent linguists who would work on the project would take everything useful from the two main dialects and graft it onto the main trunk which, in the given case, was the language of Christoforidhi.

The scientific logic of these opinions was not taken into account at the moment when a definite decision was made about the problem. In 1972, the Congress of Spelling established Toskresh as a literary and official language. It was a political decision, in which linguistic science and its criteria for determining the national literary language were subject to the “higher” will of the Party and its leader. It was the logical outcome of a thirty-year policy of terror against Greece, its culture and history. It was identified, in its overwhelming part, with “fascism”, “clericalism”, “patriarchalism”, “obscurantism”, “chauvinism”, “anti-communism” and many other isms, which aimed to distort and bury the truths historical, to use them for the benefit of the Slavic masters or the interests of the caste.

It gave a “scientific” form to political decisions, going so far as to make the infinitive disappear, a way of choosing the verb that we find in all the known languages of Europe, just because Tuscan didn’t have it. The creation of the standard was trumpeted as a great success of Albanian linguistic science, it was accepted “unanimously” in Albania and this was understandable, but it slowly found the right of citizenship in Kosovo and other Albanian countries in Tito’s Yugoslavia since then, for his reasons, was implementing a policy of liberalization towards their Albanian residents.

The acceptance by the educational and cultural institutions of the Albanians beyond the standard limit “legalized” the “language revolution” of the communist Tirana in the all-Albanian plan. What were the motives for this acceptance, they were neither scientific nor patriotic? If the Albanian linguists, among whom there were European scientists like Çabej or Domi, had their mouths “stitched” by the possibility of ending up in a cell or in the grave, the Kosovar linguists should have had the honesty and courage to oppose the decision of the official Tirana and not scientific, to forcefully impose on the Albanians and their culture the speech of less than a third of them.

The arguments made then, surprisingly by someone and today, about the damage that the national issue would suffer in such a case, are completely baseless and serve to cover the scientific and political blindness that resulted in unprincipled servility towards Enver Hoxha’s communism. If the children of Kosovo or the northern highlands have difficulty understanding the school texts, because they find a language different from the one their mother speaks at home, they should know it in honor of their fathers and grandfathers who used to beg for “Bacë Enver” and his deeds.

Now these belong to a past that cannot be returned, but like every such in history, there comes a moment that presents the account. We must think about the future so that tomorrow we do not regret today. We must set ourselves the goal that in our literary language, which is one of the most prominent indicators of our individuality as a nation, all those who speak Albanian will find something of themselves. In my opinion we must carry out, through an evolution contrary to the decisions of the Orthographic Congress of 1972, that path that would lead to the realization of the idea that had found so many supporters in the first decades of the last century. The road will be long and not easy, because by nature we are a conservative people that hardly accepts the new.

In order to achieve this undertaking, a serious and deep work of a group of researchers of the Albanian language inside and outside official Albania, led by a strong scientific personality without prejudice, under the superior guardianship of the President of the State and that of the Academy of Sciences, fully convinced of the usefulness of the initiative, having a clear desired outcome. This group should be well supported financially by the State, but without being conditioned in any direction. From time to time he has to present the results of his work before a large gathering of language workers, teachers from all Albanian provinces.

These meetings will be the anvils in which the Albanian national literary language will be forged, open to all opinions and various remarks. The work can continue for years, as the entire structure will be studied in detail, but if the goal is achieved that all Albanian children “from Tivar to Preveza” will learn with pleasure, when it has received its final form, we can say with full mouth that we have made a valuable investment for the Nation and its future.

Many may question the legality of this work, presenting it as an initiative that seeks to destroy a building, built with effort, that in the thirty years of its life has taken its full form and has a literary work in its archive and valuable translations. Thirty years is little or nothing in the long history of a Nation and if we keep in mind that they marked a black period of that history, which forcibly forced us to speak a certain language, not to pray in places of worship, not to express what we thought and not do what we wanted, I would say that any longing for her and her accomplishments seems unconvincing to me.

This does not mean that the child should be thrown out with the dirty water. Linguists will make a scientific and accurate assessment of what should be preserved and what should be changed without complex prejudices of any kind. As for the works written in today’s language, they remain the property of the nation, just like the works written in the Greek dialect. Their longevity will depend on the extent to which they will be able to withstand time and the demands of future generations.

The national literary language that would emerge from this work would be like a tree that we plant today to reap the fruits after two generations. This way we will be calm in our conscience and in the scales of history, which will judge us not only for what we do, but also for what we should have done and didn’t do.

Meanwhile, I think it would be a good idea to give the green light to writing in Greek in the press. The wall, that a good part of it has erected against these writings, seems to me to serve neither the future project of the language nor the liberal idea of society and the State. It remains a legacy of dictatorship and as such is best avoided. Regarding the language of state institutions and documents related to them, I think that the standard should continue to be used until the final approval of the new national literary language.

I wish that the mentality inherited from communism does not continue to hold language and culture hostage, as it did with the economy with very serious consequences for the inhabitants of Albania. I wish that political dictates would end in these areas that do not belong to a generation or an era, but to the nation of eternity because, no matter how we move around in this world that changes every day, we will always have one language, one flag, one Nation. Memorie.al

May 2003