Part Three

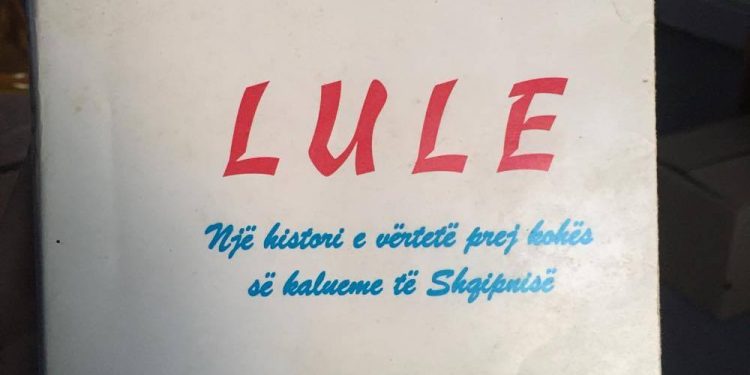

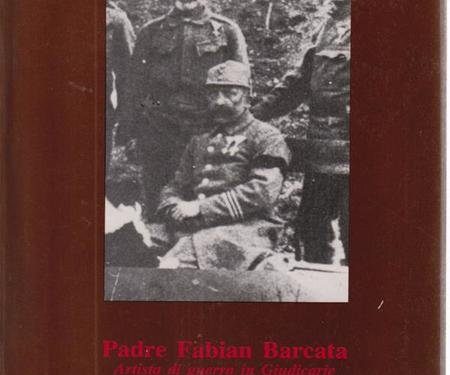

Memorie.al / “My Albanian Diary” by the Austrian parish priest, Fabian Barcata, is published for the first time in Albanian by the publishing house “Mirdita,” on its centenary. It was written in 1905-1906, in Kryezez (Rubik), and was published twenty years later in the Franciscan magazine “Franzisziglöcklein,” Austria, in 1926 – 1927. This is the first genuine diary of a foreign priest about Albania. The name of Fabian Barcata, this mystical Austrian of the last century’s beginning, is almost unknown to today’s reader. This was also the case seventy years ago, until his book “Lule” was translated and published in the Albanian language, thanks to the care of Professor Karl Gurakuqi, one of the piquant names of Albanian literature and culture, who died in Rome as a political emigrant in 1971.

Continued from the previous issue

A figure like Barcata brings honor to Austria itself

“MY ALBANIAN DIARY”

(Excerpt from the diary…)

By Father Fabian Barcata

MELANCHOLY

“The hours when I get homesick”

September 20, 1905

The heart is a special thing. What it has and what it owns is of no use to it. Its purpose is to reach what is far and impenetrable. Am I not happy, do I not have a sphere of activity that every priest would envy? Do people not love me with their childlike affection?

Oh, I am not very grateful that I don’t always have such things before my eyes. Even though I later feel ashamed, I cannot escape the hours when a great sadness stirs my soul, where the heart flees with that painful longing, the hours when I get homesick. This brings nothing.

This is how we are from Tyrol, and even God up there, who puts the longing for our homeland’s mountains into our hearts, would not hold it against me. When my thoughts go back to my homeland, when the images of my homeland appear before my eyes—my parents, brothers, and sisters, friends, relatives, fellow countrymen—being here seems so boring, and my current life resembles a desert, and on this desert, somewhere far away, like a fata morgana, is the past, full of light and wonder.

At such moments, reason is useless, you cannot control yourself. I often go far, up to the peak of Qafa e Fikut, where my sight crosses over Molung and to the lake and from there, on to the north, where Tyrol, my homeland, stretches out in the misty distance. And when I have had my fill of looking and when this storm finds a place in my heart, I slowly return to my residence and lovingly carry out my duties.

Fortunately, these turbulent hours are not that frequent. It was even worse in Lezha. There, I fought melancholy with other means. I had the horse saddled and quickly left again, jumping over stakes and stones, pits and hills, always faster and faster. The wilder the journey, the faster I would regain myself. – Tu autem, Domine, miserere mei…!

BLOOD FEUD

“What is the use of hatred, Mark Pali?”

November 7, 1905

Today I allowed Mark Pali to come to me. He has been in a blood feud with the Kovaçi family for a long time. Someone from the Kovaçi family had killed his son. This had happened seven years ago. I wanted to intervene and for this, I pleaded with him with convincing words to forgive and forget. “What is the use of hatred? With it, you bring yourself dissatisfaction, while also destroying the murderer’s family. Seven years have passed since the death of the child, and you have not been able to get revenge so far because the Kovaçi family and clan have fled and wander like homeless people in this big world!”

The man looked at the fire (we were in the kitchen) and didn’t even want to hear about reconciliation. When he got up to leave, I walked with him for a while. We had to pass the cemetery. Suddenly he stopped there, gestured with his hand toward one grave, then toward another, and said to me: “Here, the mother of my child pulled out her hair; here, the mother of the murderer must also pull out her hair.”

SUPERSTITION

A victim of superstitions

February 10, 1906

Today I returned from Kallmet. I had stayed all week to paint the monastery chapel. When I got home, I was given some sad news. Three days ago, a poor gypsy had been here. He was old, powerless, and almost naked. He had asked for alms everywhere and then had come to the parish. Mark had given him a piece of bread and a bowl of beans, which he devoured like a madman.

Then he had left and this morning they found him in Velë, like a dead dog. A victim of superstitions. The people who had sentenced him to death may have thought he was some kind of evil spirit or a devil! I am happy that it did not happen in Kryezez, because for God’s sake, it would be no laughing matter.

THE WONDER

Pagan superstition: fear of spirits and old rituals for burying children!

April 21, 1906

I now understand how triumphant my work has been. Everywhere in this country, a treacherous disease threatens. In Manati alone, twenty people have died, and even the priest is affected and has no hope. Here in Kryezez, a single child died, and it was in the very house where this disease had first appeared.

The necessity that dominates this place for the burial of small children is ugly and almost entirely pagan. Yesterday afternoon, after returning from Kallmet, I heard for a long time, without yet reaching the cemetery, a sad and quite long wailing tone. It was only one voice wailing. When I got there, I saw a man who had started the work of digging a small grave.

On the ground, next to him, was a small cradle and in it a dead child. Above the cradle, a young woman was bent over, kneeling, expressing her pain with touching words, which were sometimes in a half-voice and sometimes very loud. It had been her first and only child. I was a little angry because I had often told people to call me for the burial of children as well as adults.

I could never find out why they secretly buried the children. Is it superstition or shame, pain, or fear of bothering the priest too much? Or is it all of these? Yesterday I came at the right time. I started to speak to the woman in a harsh tone, but when I saw that deep and great pain on her face and all over her body, I fell silent. I got off my horse, tied the reins to a grave cross, went into the church, and quickly returned with the clothes I used to chant and with a cloak.

I blessed the grave and the small corpse. The mother was silent, and with wide eyes, she looked sometimes at the dead child, sometimes at the grave, and sometimes at me. Large tears weighed on her eyelashes. They put the child in the grave, placed the boards of the broken cradle over the small body, and then closed the grave. I went to the parish, and an hour later I heard the frightened wail of the young woman. In the meantime, I heard someone talking in the kitchen; a servant opened the door and said to me: “A woman wants to talk to you.”

I went out and found myself in front of the mother of the dead child. She came up to me, took my right hand, brought it to her lips, and said: “Sir, may God bless you, keep your days, and increase your strength. As an uneducated woman, I cannot do anything else but thank you for having given my Zef so many honors for his death.”

I asked my servant Gjergj why they broke the cradle when they wanted to bury a child. He told me that it was a custom of the people because they thought that any child who would sleep in the cradle of a dead child would die immediately after him. For this reason, a new cradle had to be made.

There is also something else that worries me. The small depth of the grave. Sometimes it is thirty to forty centimeters deep. It has often happened that dogs and pigs have opened such graves and enjoyed themselves, mercilessly eating the flesh of the corpses.

Some time ago, one of my servants told me a terrible story that had happened to my predecessor, Dom Prendi. They had buried a child, and that same night, a child’s loud cry was heard in the rain. It was the child they thought had died. The servants and the priest had heard the child’s crying.

However, no one dared to go more than seventy steps to the cemetery, as they thought it was a spirit and were very afraid. The next day, the grave was completely ruined. During the struggle for life, the poor little one had extended one hand out of the earth, from which his small, cold fist was visible. A poor victim of the fear of spirits. And this thing is impossible to cure.

I see this in my servants as well. For example, in the dark, none of them would go to the cemetery, even if they were given all the gold in the world. The road to the parish is to pass among the graves, and sometimes it happens that because of some work, they have to return or leave the house late.

For this, they have always taken the long way around, just to avoid passing through the cemetery. When I gave them an example, they would reply as usual: “Well, it’s easy for you because you’re a priest, and no spirits come out to a priest, and no one harms him.” They know how to tell the most frightening stories.

About vampires that came out of graves at night to drink the heart’s blood of people. In fact, one of them told how his donkey had stood in the forest, hidden behind a stone, trembling with fear, and it was impossible to make it walk. Sometime later, he had learned that a man had been buried there.

He was convinced that it had been a spirit that had frightened the donkey. There were evenings when they would bet on who could tell the most frightening story. And the next day, they would tell me they couldn’t sleep all night. / Memorie.al