By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part nine SPAÇI

– The Grave of the Living –

Tirana, 2018

(My own and others’ memoirs)

Memorie.al / Now in my old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of the others whom the regime silenced and buried in unnamed graves? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, although I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you have only two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days, I would not want to take to my grave.

Continuation from the previous issue

“For breakfast, they shared a watery soup with a few grains of rice, or star-shaped pasta that concealed flies, and sometimes even worms, in the caviars that served as the morning garnish. When lunchtime came, which was almost rich, despite being served nine to twelve hours after breakfast – a gap that acted as an appetizer and offered the “enemies” the opportunity to enjoy the food and swallow it without fuss, along with everything it contained, because they returned hungry.

So, lunch, being the richest meal, was based on vegetables, because the regime adhered to vegetarian recipes, considering them the healthiest. Twenty-two grams of meat were also planned in the norm, although its smell was not sensed for days and weeks, let alone finding any strand, because it ended up in the bowls of individuals with real contributions, the clerks of the technical offices, the spies who returned from the “battlefields” of supply and the prisons, with new draft animals; and, not infrequently, into the mess tins of the police officers. Few or no bones were thrown into the common cauldron.

As I said, the base of lunch consisted of vegetables, which were divided according to the season: spring, summer-autumn, and winter. In spring vegetables, spinach and spring onions held the top spot, which they threw uncleaned into the cauldron, or cut into two pieces, to utilize the maximum amount of mineral salts from the soil where they had grown, and plunged them to boil with the roots, adding a few drops of oil, even though the norm was twelve grams.

Through this unwritten rule, they kept the enemies away from cholesterol and fat. Thus, they used vegetable oil, sunflower or cotton mixed with pig lard, and often even whale oil to multiply the nutritional values.

Thanks to the Party’s “paternal” care, at the transition from spring to summer, the number of vegetables increased, consequently increasing the variety, although for May, June, and all of July, the base remained the onion, but grown now. So, they put the onion head with its stalks into the cauldron, to increase the concentration of mineral salts; relying on the fisherman’s joke about the old fish, who had released it when it was small to grow, and when he caught it old and it begged him to spare it because its flesh was now weak, he replied with the wisest sentence that came to his brain: “There is no such thing as old onion and ancient fish! The old onion is sweeter; the ancient fish is tastier!” and he baked it on tiles. To enhance the flavor, they threw in a few handfuls of peas, or dried beans, while spices were not recommended, as they made the consumers fussy.

In the months of August, September, and October, the problem was solved; the “blue beauty,” cut into quarters, reigned in the prison cauldron. When you saw it proudly floating on the black water, your appetite would be cut short and your diet prolonged; rarely did some wrinkled tomato or pepper show up, which they brought when they rotted in the fields.

With the first frost, the cauldron changed content. To increase the caloric value, you couldn’t find a more ideal vegetable than the leek, which someone called “Presh” (Leek), another “Purri” (Leek), others “the tall one,” and the jokers “Akil”- not a classic epithet devised by the nostalgic admirers of the famous Achilles Pelides of old Homer’s Iliad, but of another Akil, who became an epoch in prisons and became famous for the failed assassination attempt he would have wanted to make on the members of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania, during the fiftieth-anniversary celebrations of Independence, in Ismail Qemali’s heroic Vlora, despite the fact that this notion had never crossed his mind!

In the absence of a monument for the failed assassination attempt, the Shkodrans immortalized “Akil Kurbini” in the culinary art of survival; an inseparable dish, for nearly five months, was baptized “Akil’s recipe.” The weak, thin, tall, dry Akil, with a disproportionate body and kilometer-long limbs, nearly twice the size of his torso, and a head that began with a pointed tuft and ended with a pointed chin, where a clump of hairs resembling leek roots came to a point, gave the Shkodrans, known for their teasing, an opportunity to mock him: “Purri Beltoje” (Beltoja Leek) or “Kavak Stajge” (Stajge Poplar), and they nicknamed the winter-early spring main dish “Akil’s Recipe,” and to distinguish it, they added: “from the tall one.”

The Philhellene Vas Gavoçi, passionate about ancient Greek and Greek mythology of antiquity, ate bread with his compatriot, Shtjefën Lacuku. But Vasi would get lost and engrossed in the classics, so the daily “trifles” were left to Tefa, who, as agile as a squirrel and small as a bead, but as witty as he was, would take the portions and wait for Vasi, who turned page after page in conversation with the classics, until the dish became stiff on the plywood tray. “The dish is cold, Vasi!” Tefa reminded him. “What dish do we have today, Tef?” Vasi asked, coming to. “May God help us; we have the queen of cuisine, the most marvelous, noblest, and tastiest dish that the human brain has invented: we have ‘Akil’!” “Leave Akil in his antiquity, don’t mix him with today’s scum, man!” Vasi begged him. “No, my dear, I’m not talking about your Akil Pelides, but about this ‘tall one,’ the leek of Beltoja! Or didn’t they cut it so your eye could be satisfied!” Tefa replied brazenly.

The companion of “the tall one” was the noble arme cabbage, which cut the appetite of football lovers just by seeing it cut into pieces; on the contrary, when a whole head floated in the cauldron, they would go into a frenzy, betting a week’s food with each other and quarreling over who would find the uncut ball. When my professor, Shyqyri Gruda, a former “Vllaznia” and national team football player, managed to get hold of (pardon me, into his bowl) an uncut cabbage, he almost lost his mind from the satisfaction of achieving such bliss and wandered from dormitory to dormitory, and from nook to nook, with the bowl in hand. He even wanted to demonstrate it in the cells, to boast to the isolated about the miracle that fate (pardon me, the cook) had brought him. Exclamations caught Jemini when he approached Sefedin, the distinguished goalkeeper: “Look, Sef, what a silver-colored ball, not even Pelé could score this pearl! Honestly, I never got to see such beauty, not even when I played myself! Now fate (pardon me, the cook) brought it to me, and I won’t let it go!” “May you benefit from it, dear Shyq, I wouldn’t even try to cut that ball!” replied the national team’s second goalkeeper. Shyqi benefited from the cabbage head; Shahin Skura, (the camp commissar), gave him a month of “winter holidays” in… the cells.

Dinner was screened out by several medical commissions, who “invented” scientific recipes: initially not to give it at all, not to save state reserves, which were full, but to maintain physical condition and protect the enemies from the epidemic of overeating, because they feared obesity, with all its unpleasant consequences. With an empty stomach, the person felt comfortable, slept lightly, and was not bothered by gases; they felt no stomach pain due to difficult digestion. I am talking about those who suffered from silent ulcers and aggravated gastritis, although no one slept due to the persistent gnawing of empty intestines.

For the “six-hundreds” (those on the lowest ration) and others belonging to this category, this diet remained in force until ’91 when the prisons were closed. However, the menu produced terrible results! It saved thousands of wretches from the effort of dragging themselves on the ground, throughout the territory where there were political prisons and camps; it increased the number of nameless graves, consequently fertilizing the lands of the Homeland.

Thus, based on “humane and medical principles,” a light ration was introduced for the workers, specifically to protect them from the “disease of overeating.” They shared a reddish liquid called tea, where the presence of sugar was barely discernible, although the papers spoke of twelve grams. However, based on the aforementioned limits, this amount was never added, because the regime aimed to “protect” the enemies from diabetes, the devastating scourge of the century that even their Enver suffered from. The fear that they might run out of opponents forced them to be cautious, because ultimately, who would they clash with then?! And the paper amount was reduced to two grams. The slop was bitterly poisonous, so much so that you couldn’t put it in your mouth, and it emitted an aroma that brought your intestines to your throat; (it released a smell of chlorine, mixed with I don’t know what heavy-smelling medicine, which they added to prevent men from becoming aroused… because then, good luck satisfying their needs!)

Without the dedication and sacrifices of our family members, as well as mutual solidarity, today the interesting species “former political prisoner” would not be heard of; and if one were to be found, they would belong to the category that were favored by commands, the fortunate kitchen workers, and the scoundrels of Mehdi Noku.

The History of the Ration Let’s return to the topic. The communists aimed to exploit the enslaved working-animals for free, as they considered those confined within the barbed wires. But to reach record capacities, they had to increase their ration. As early as ’45, the elite of the nation was locked up in prisons. Unlimited investigation, physical torture, a depleting diet, the deliberate lack of healthcare, plus work with extended hours, which turned the unfortunate into skeletons without an ounce of strength, as well as their advancing age, increased the deaths and the decimation continued, although the number of convicts multiplied several times.

Despite the leaders’ claim of a normal country, with normal conditions and a normal government, the opposite of what happens in the democratic world occurred in Albania, where governments, as soon as they take power, restore order, strengthen the economy, condemn the crimes of their predecessors if the culprits are found, and close the accounts with the past. While deepening progress and punishing corruption to maintain macroeconomic stability, they condemn ordinary crime without compromise and stop in the political aspect.

But what happened in communist Albania? The further we moved from ’44, the more the number of “enemies” grew. With only three articles: for “attempted escape,” for “alleged terrorism” against state personalities, and for “agitation and propaganda,” they filled the prisons to the brim. These vampire articles swallowed up everyone from the ideological opponents of the Communist Party to the wretches who shed blood for Enver.

Ideological opponents constituted the first contingent of political prisoners in post-war Albania. This idealist-nationalist conglomerate represented everyone from the wealthy and middle strata, the traditional intelligentsia, to ordinary citizens or peasants who were involved in opposing ranks. This amalgamation included high and middle-level officials, a legacy of the Ottoman Empire, to the young woman educated in the West, whom the former considered a regression for the prospect of the future. Among them were anarchists and Jacobins of ’24, later liberals and social-democrats, who, despite their ideological contradictions and disagreements on the nation’s well-being, found themselves under the crushing force of the communist mill after the war’s end, like Odysseus between Scylla and Charybdis; they were lined up on the losing side and declared enemies, without considering their political incompatibilities.

The communists emphasized divisive propaganda, seeing an enemy of the people in every opponent, regardless of the fact that the majority dedicated everything they had to the national cause and sacrificed themselves in the name of Albania. They were all thrown into one bag, without hesitation, and after this, the consequences were tragic; their contributions were valued at zero, they were accused of archaic nationalism and precisely for these reasons, the burden of accusations was aggravated, implying they hindered prosperity in the name of Greater Albania.

To fully form the army of enemies, those thousands of Albanians of modest origin must also be mentioned, but with endless love for the people and the homeland, who even dedicated their lives. But for the communists, these remained just as much enemies as the former, if not more, because they started the war before the persimmons ripened and struck the Italian “liberator-invader” without waiting for Father Stalin’s order and without getting the approval of the Comintern, even though they lined up alongside those with the ‘Balli’ (National Front) and Legality, without their full consent.

According to the peasant-Leninist viewpoint, adherence to “opposing formations,” consequently hostile, constituted a crime, so everyone who joined their ranks had to be viewed as a traitor to the people and the Homeland. Since they agreed to fight without the consent of the conductor Tito, as the guarantor of Father Stalin, they were labeled: collaborators. So, this contingent of modest origin was also lined up in the “enemy” phalanxes.

Some of the aforementioned went to the rope and the bullet; those who overdid it were exiled to extermination camps, in housing construction, marsh drainage, land reclamation, factory and plant construction, etc.

The later convicts were derivatives of the first convicts and belonged to the most suffering contingent of communist Albania, who were seized from the internment places where they had been banished, accused of high treason, and put in camps, although they were no different from prisons, in which the same forms were applied, albeit in a wider enclosure and with fewer guards.

But even these were dwindling. The natural number decreased, because they either died in prisons or, if they came out alive, they were old and incapable of reproduction. To multiply the number of slave-working-animals, the method had to be perfected. The Security (Sigurimi) became a master of manipulation and an innovator in the craft, finding it easy to seek and find new resources, even pruning the branches of its own tree.

The system built on foundations of blood and based on the dogma of Marxist philosophy could not survive without fueling the fire of class warfare, not only among the people but also within the party, where they incited the existence of permanent antagonism, allegedly in the name of ideological purity, where they increased the pace of terror, declaring the opponent necessarily an enemy, and eliminating them without hesitation as such.

“We will find the enemy wherever he hides, in every social formation, in every village, in every city, in every neighborhood, in every mahalla (quarter), in every collective, in every group, even when he doesn’t exist, we will invent him, we will clean the metastases and throw them to hell, to heal the Party and keep the cell pure.” This was preached by the all-powerful “Zeus,” and the hounds went on the offensive!

They started a game of elbows for personal power, deepened it, and continued it as class pathology to maintain the power gained through elbows, until the revolution ate the “heroes” it bore, like the sow her piglets. The rest of the contour was filled with the litter of the red sox, so that no house remained without an enemy and no tribe without two kulaks; one in prison, the others in internment.

Spionage became a profession of honor; the son spied on the mother to the operative; the wife on the husband, to the Head of the Council; the daughter on the father, to the Bureau Secretary.

Convicting someone of political crimes was the easiest thing. Article “73” (Article “55” in the new Constitution) extended indefinitely. This octopus-article thrust its tentacles into every cell of society, became the ear and the eye in the door cracks, plunged its claws into every nook, from the marital bed to the plenums of the Political Bureau, and like a circular fugue, it encompassed countless people in its hooks, from the glorifiers of the enlightened leader to the critics. The effects of the fugue-article, which revolved in the twenty-eight thousand square kilometers and dragged to hell whatever it encountered, were felt on the backs of ordinary people, right up to the untouchable members of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the PPSh (Party of Labour of Albania).

Thus, even members of the caste were lined up in the “enemy” phalanxes, and their number multiplied so much that towards the end, it was unclear who was left unincluded in this army!

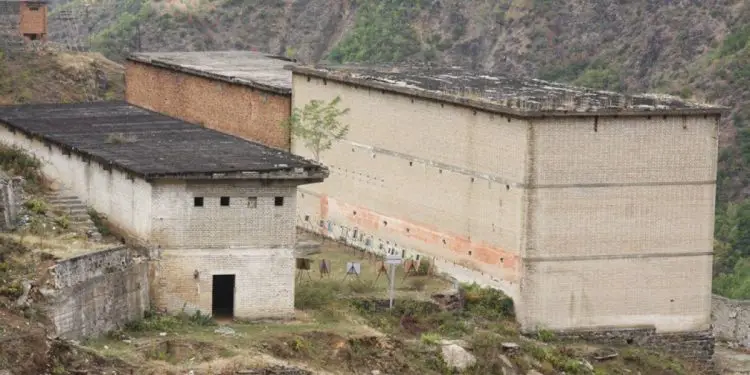

The increased phalanxes engaged the government to find ways to exploit this super-force. Hence, new fronts were opened: the galleries of Spaç, the mines of Qafë-Bari, etc., where the younger convicts were sent.

But work in the mines was many times harder and the environments damaging; the slaves were getting sick and falling down in heaps like chickens with the plague, the prison hospital had no more free beds, the cemeteries were full, self-harm doubled, the rebellion was growing, consequently, the norm was not realized, and the plan was not fulfilled.

But the government, which started with one-year, two-year, five-year plans, even though they were never realized, interpreted non-realization as failure and did not tolerate it. Thus, to escape bankruptcy and increase the yield of the slave-working-animals, they increased the “ration.” This is where the Spaç diet begins, where, unlike other prisons, the norm was slightly increased.

Meanwhile, the differentiated diet continued. The division into workers and “six-hundreds,” who formed a negligible minority, because whoever ended up like that was transferred elsewhere. Even the workers themselves were divided: into surface workers and auxiliary sectors, who received the usual diet, and miners, who were the beneficiaries of the diet in question.

Working underground was not an enviable privilege, due to the almost infernal environmental conditions that made life unbearable. As soon as you poked your head into the gallery, even at the mouth, you felt a whitish steam with a smell of mold, which floated in the air even in mid-August. When the drought was suffocating outside, at the mouth of the mine, dew sparkled on your brow. Especially inside, where the dampness ground you down, and as you pushed deeper, the vapors covered you head to toe.

Besides the humidity, you had to endure the smoke from the gases of dynamite and carbide, which turned the convicts into asthmatics within the first months, making them vomit bile, and along with the phlegm, they coughed up streaks of blood. This phenomenon was found in every corner, especially near the latrines and taps, where you found yellow, black phlegm mixed with clots of blood; meaning the rock silicate, acetylene, and tritol particles had done their work.

In addition to silicates and poisonous gases, billions of deadly bacilli and bacteria attacked, finding paradise in the immune-deficient organisms of the convicts, multiplying and gnawing at vital organs, then migrating to others, until the epidemic affected the entire camp.

Work in the mines damaged mental health; when you entered the holes, you thought you were living your last day. Hence, the typical greeting from the escorts: “God keep you!” and from the one being escorted: “Forgive me,” were two monotypic phrases that unravel the psychological drama of the miner. Memorie.al