By Bashkim Trenova

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their sucklings, whom he described with a rare skill in a memoir book published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

Enemies of the people

Kosturi was the first “enemy of the people” with whom I “encountered” in my newly started life, without knowing him and without ever knowing me. Later, growing up, I saw that the enemies were numerous, they were constant companions of my life. “The enemy of the people”, was the fatal shadow of every Albanian. To be or not to be of every Albanian, depended on the humor, caprices and selfishness of the dictator, his court and sejmen. Arbitrariness and disobedience to the law were law. Sicily, at any moment, could be declared by the government from the former loyal to his death, to a sworn enemy from the first day of his birth, in short “enemy of the people”.

Poverty, the real enemy of the people

As far as I can remember from our several years of life in Durrës, the real enemy of the people was the great post-war poverty. The power established after the liberation of the country from the Nazis lacked both tools and experience. The new rulers would prove over the years that they were utterly incompetent, irresponsible, and unworthy to run a state. Neither in the first years after the war nor beyond could they build a secure future by first fighting the real enemies – poverty and ignorance?

Indeed, in the field of education and culture, several courses were opened against illiteracy throughout the country, then a wide school network was set up, the University of Tirana, the Opera and Ballet Theater was set up for the first time, etc. At the same time the circulation of different philosophies and ideas was banned, the circulation of different artistic-literary currents was banned, the foreign book. Everything was forbidden, except poverty. Poverty was another thing. It could not be fought either with courses or with the enthusiasm of slogans. Invincible by communism it will defeat communism. He “forgot” his basic teaching according to which “matter is primary, idea is secondary”. He simply changed places or was forced to change places for them, thus betraying himself, which paid off like any betrayal.

In the hills of Durrës, we ate thorns to quench our hunger

The years passed and I remember how together with Diun and other children of the family who came from the south and who lived near us, we went to graze the goat in the hills of the city, where the castle was erected. The goat fed the children of this family so even though it settled in the city, it kept it as its greatest asset. While grazing, we plucked the stalks of some thorns, removed the thorns, peeled the skin, and ate them as delicious food. I saw others and did like them. Simply, we all tried to eat almost like goats.

In the hills of Durrës castle there was also a hospital for the disabled as well as an Orthodox church and a cemetery for its believers. We as children rejoiced when there was a funeral ceremony and were nearby. It was not the religious ceremony, the respective rises that attracted us. We did not understand them, just as we did not understand life or death at this age. According to the Orthodox rite, at the end of the burial of the deceased, at the entrance of the cemetery, a handful of sweet wheat was distributed to those present and passers-by. It was this handful of wheat that drew us all joy even though it dissipated for sadness. Our hunger was part of the sadness.

I remember how in a grocery store, my neighbors waited for a buyer to throw away the leftover fruit eaten to pick it up and feed it. I remember how one day our mother beat her sister, Engjëllushen, who at that time was not more than ten years old. Why? Because he had asked her to prepare pasta for lunch. The sister forgot or left the pasta on the fire for a little longer and they burned. This meant that we would be left without food. There was nothing else in the house. That’s why in despair, the mother beat him. I remember how all of us children got scabies and how we applied sulfur to heal. Burning sulfur in the hands and body was unbearable.

Scheduled food that came as outside help and social canteens

Later, in kindergartens and schools, aid brought to Albania by international institutions began to be distributed, powdered milk, marmalade and similar artificial butter. We, no matter how hungry we were, could not swallow the “gifts” that came to us from across the Adriatic. In fact, they were filed and smelled so bad that you could not even approach them with gas. Often, as we got them, we buried them. In schoolyards they started giving us even a spoonful of fish oil. His opposition was overwhelming. To swallow the fish oil, we accompanied its drinking with a piece of bread brought with us from home and with one hand closing the nostrils. A few grams of jam, the size of a candy, were our happiness.

Special event was when we went to social canteens. My parents and I sat at long desks, waiting for hundreds and hundreds of citizens, who seemed to me cheerful, noisy. I do not know how they were organized and who could benefit from them. It is possible that the state in this way helped the employees engaged in its administration, such as my parents! It seemed to me as if the whole city was there.

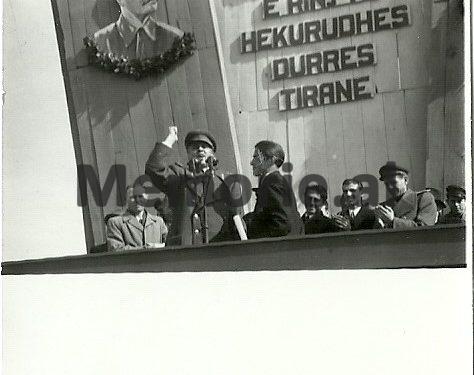

Special event, the inauguration of the Durrës-Peqin railway

A special event during my family’s stay in Durrës, was the construction of the Durrës-Peqin railway, in 1947. This is how the construction of the railway network began for the first time in Albania. To host or escort the first train, a grand rally was held, attended by large and small. It was not just curiosity about something new that was entering our lives, but also a proof that the hopes for a new life had begun to come true. So said the Communist Party, which surprisingly, although in power, continued to remain illegal, as in the years of the War.

When the locomotive gave the signal of the arrival or departure of the train, the enthusiasm of those present was incomparable. Songs were played, dances were thrown, Albanian and Yugoslav flags were waved in the air. At the front of the locomotive were a portrait of Stalin, Albanian and Yugoslav flags, as well as portraits of the communist leaders of the two countries, Enver Hoxha and Josif Broz Tito. From the crowd was heard the very popular song “Druzhe Tito, druzhe Tito”. It would not be long before the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of Albania, Druzhe Tito, would declare itself the greatest enemy of the Albanian people.

But with this enemy former friend, I will not go on because he has never been either a friend, or a friend, nor a relative, a neighbor or a colleague of mine, so it is outside the realm of my story. I can only say that the locomotives and wagons that came from Yugoslavia as a precious internationalist gift to Albania, belonged to the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Druzhe Tito thus passed to Albania the old stocks as “fraternal aid.” The Albanian communist leadership was exalted before this “help”.

From Durrës, again living in Tirana and with the “enemies of the people”

After a few years we left Durrës and returned to Tirana. The same thing as with the Austro-Hungarian wagons coming from Yugoslavia, I saw in the Textile Factory “Stalin” in Tirana, only a few years later. This time it would be the Soviet comrades who showed their “internationalism”, using Albania as a rubbish bin, or as a graveyard of Tsarist-era machinery of the 19th century. The Albanian communist leadership, for about two decades, continued to sell its exaltation as our happiness, garbage as locomotives of progress. I will not stay here either because the study of the relations between the Albanian Communist Party and the Soviet one is not in the sphere of these notes.

I can only say that just like the Yugoslav leadership in 1948, the Soviet leadership, in 1960, was declared by Enver Hoxha and the Albanian Labor Party, as a sworn enemy of the Albanian people and all freedom-loving peoples, as an agent of imperialism. , etc., etc. In Albania, before these positions of the Labor Party, there were people who saw the rulers of Belgrade and the Kremlin as fierce enemies of the Albanian people. Even if only for this, they have been declared by the communist dictatorship of Tirana, as “enemies of the Albanian people.” The dictatorship gave itself the exclusive right to declare great friends and great enemies of the Albanian people, to turn lifelong friends into sworn enemies and vice versa, if its interests so required.

Alfred Bonati, the second “enemy of the people” I knew after Kostur!

The first problem after returning to Tirana was that of housing. If in Durrës we took refuge as tenants in the house of an enemy, in Tirana, an “enemy” was like a tenant in our house. In fact, during our absence, two other people were sheltered there. One of them was the famous goalkeeper of Sport-Club “17 Nëntori”, as well as the national team, Alfred Bonati. He kept a room of ours for a few more weeks or months after we returned from Durrës. Bonati was with a sporty body, quite charming. All the children and young people on our street greeted him with the desire to receive a greeting from him in return. I did like everyone else, even feeling superior because he was “indebted” to our family. He continued to stay in the room that belonged to us and that he should have left in time. I did not know then that Bonati was the second “enemy” I was facing in my life. He also had something in his biography that did not go well with the so-called popular power in Albania.

What was Bonat’s “crime”? I have never learned this either. What I do know is that Bonati, who was the star of our football in the first years after the war, ended up as a simple driver at the Kinostudio “Shqipëria e re”. What I do know is that on December 6, 1946, he was arrested in Albania by the Monsignor State Security, Prof. Jul Bonati. He, at the age of 73, was sentenced to 7 years in prison on charges of “Vatican spy”, which he never completed. After the sentence, the government “took interest” in his health and sent him to the psychiatric hospital in Durrës. One day, on May 5, 1951, the card was filled in the hospital: “Jul Bonati died …”!

Did the time-adored goalkeeper Alfred Bonati have any kinship with the erudite clergyman Jul Bonati? Maybe yes Maybe not. For the regime in power, it was the same anyway. Alfred Bonati, even if he had a blood relationship with Jul Bonati, was tainted in his biography, but even if the common “Bonati” was just a coincidence, such coincidences were not easily forgiven under communism. They, however, indicated a connection, even distant. Security was vigilant!

In Tirana our house was located at the entrance of a dead end alley. In my childhood it did not occur to me to divide its inhabitants into communists and non-communists, into patriots and traitors, pro-government or anti-government. As children we played together without knowing the differences mentioned. As children we gathered and talked fiercely opposing each other about different facts and events. Here, as I think now, each of us, as instinctively, defended the “class” position, i.e. he lined up in the camp where his family, parents and cousins also belonged.

The “Parliament” of the children, at Vakëfi near the oven of Isuf Larushku

Almost every evening we gathered near Isuf Larushku’s kiln, not far from which was placed a small concrete block measuring 50 cm high and 30 cm wide, which we also used to sit on. This block, on which the word “Waqf” was written, indicated that the surrounding area was sacred, or that the surrounding lands belonged to a religious community, in this case a Muslim one. Next to the block was an electric pole at the heights of which barely lit a lamp too small for the space it had to cover.

Two were our unrestrained “heroes”, the fiery Hamit Kolaveri and the pathetic Behxhet Agolli. Sometimes I even uttered a word in this “assembly” of men, even though I was the youngest among them. Everyone participated in the conversation. The blood was heating up like in the current Parliament of Albania, but we were honest, we never cursed each other and it never even occurred to us to viciously accuse each other, let alone denounce one or the other. We were young or children, but we had faith and manhood, we inherited another upbringing.

From the square where we gathered for the “assembly” passed the cart that transported the dead to the city cemetery. We did not know who was being buried, what class or social stratum the deceased or deceased belonged to, whether he had been a patriot or a traitor, a communist or an anti-communist, a son of the people or an enemy of the people. For us the dead, whoever they had been, had to be honored and we interrupted every debate, every game, got to our feet and stood motionless overlooking the procession until he left. There were also cases when this rule was not respected by us, but for completely different reasons than I mentioned. We often saw, for example, a somewhat broken man with a small coffin on his back pass in front of us. We called it the porter. Maybe that’s what others called them. This could be recognized in the official staff where he was employed.

He carried stillborn babies or stillbirths. These were then buried as nobody’s children, as non-existent, ie unaccompanied by anyone. Sometimes he paused to relax and lowered the small coffin down from his shoulders. Once, in such a case, we asked him to open the lid of the coffin and see what was inside. We wanted to see death. He accepted and we saw, for the first time, a dead being, a completely naked child inserted into this crate of raw planks that we called a coffin. Surprisingly a gut hung from the navel above the body!

After the loader left with the small coffin on his back, we lit a big fire and gathered around him to repeat who for the seventh time in the same place, the same scary tales, legends, anecdotes, stories, truths and fabrication. We talked about Selman, a fruit and vegetable seller who had died and who, as the saying goes, had spilled out because he had cheated on weight. We talked about the former director of the school “Kongresi i Lushnjes”, Mehmet Alizotin. It was also said that after he was buried, passers-by had heard his cries from the depths of the grave. Stuck by stories of this nature, near the fire, which we lit almost regularly, the anger of our two “heroes”, Hamit and Behxhet, was extinguished. There were other successful tenors. Gimi i Fajës, for example, surprised us with his repeated erotic adventures on the city bus, etc! To stimulate his imagination we pretended to trust him.

Hamiti, originally from Mati, with his father a political prisoner, as a former gendarme

Hamiti was originally from the North of Albania, from the province of Mat. His house was in front of our house. Behxhet was originally from the north, from Dibra. His house was separated by a courtyard wall with ours. Hamiti had pasted a strip of paper on the front door of his house, marked “Arsen Lupen” or “Al Capone” in black, I do not remember well. I do not know why he did this! He lived with his grandfather and grandmother. His father had been imprisoned because he had served in the gendarmerie during the occupation. He was denounced by officials of Berat, a city in the center of Albania, where his wife was also from. The residents of our street had not filed any lawsuit nor had they accused him of any concrete action in the service of the invaders. In fact he had made a deaf ear and a blind eye to what was happening in our alley. Honor asked him not to denounce the neighbors even though any of them, such as e.g. My family or that of Behxhet, were fully engaged in the side of the anti-fascist resistance, despite the fact that in our homes illegal meetings were held or aid was collected and distributed to the families of the partisans, the leaders of the anti-fascist armed formations were also sheltered. To him, all this had not been unknown.

Hamit saw and judged things through the eyes of a teenager, who felt persecuted. He could barely make a living. It was my uncle, Fadil Trenova, who worked as an agronomist in the Municipality of Tirana, who set up a garden in the square where we had our “pluralistic” “debates”. Hamit’s grandfather and grandmother were employed there, thus ensuring their existence and that of their nephew. Hamit’s mother had left Tirana and was living in her hometown of Berat.

As if the worries that had fallen on their shoulders and for which he and his grandfather or grandmother had no responsibility were not enough, the state took care to make their lives as stressful as possible. Thus, without their consent as homeowners, two other families were introduced as tenants. That was not enough. In the backyard was erected a shack covered with cardboard and sheet metal, which the Kolaveri family used as a warehouse. A gypsy family with many children entered there as tenants. Grandpa, Grandma and Hamit were left with a small room to live in. Memorie.al