By Ndue Dedaj

From the series: “Encyclopedia of Simple People”

Memorie.al / I am saying that at the beginning of the time, I would have liked to read the lives of people, neither distinguished nor unremarkable, not because a few people on this earth have not done great deeds for the benefit of humanity, for which they should always be mentioned in life, but because, in their “image”, there are infinite people who have not done anything remarkable, but who miraculously possess the “art” of pretending to be great people.

And when it happens that they are leaders, then a multitude of official officials and information tools work for their fame, up to the last, Tik-Tok, in multiplication of their voice, image and ordinary name. Therefore, as a sign of rejection of this category, which has not been left behind by history, but has tried to drag history behind them like a mule, I have decided to write the encyclopedia of unknown people, with their permission and in their honor, of course in complete opposition to the “normative” writers of books about unknown notables, as is happening with all the directors and mayors of yesterday’s province, some of whom were devoted “party workers” and sworn servile servants of the highest bosses.

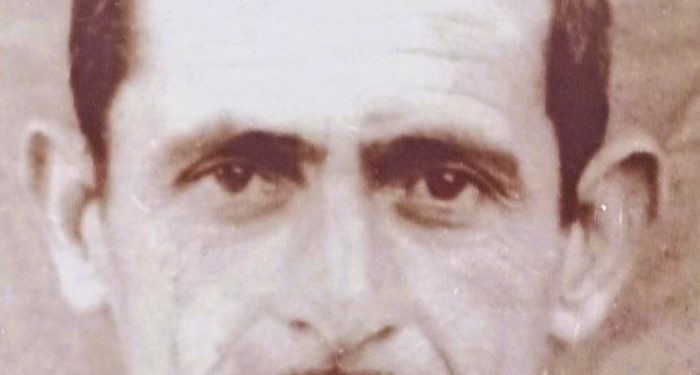

The first in this encyclopedia of ordinary people is my father, Mark, whose life, according to the standard requirements of today’s official CV, does not mark anything special. He was born in 1923 in Rrasa e Zezë and knew only how to read and write, without going to a single day of school, but after overcoming illiteracy himself, he wrote a little when he needed to (he didn’t put his finger on the paper like his grandfather) and read books and newspapers. He sometimes sang for fun in the evenings at home, but he had no talent, and only if there was no one else to tell him, he would sing at the men’s table at weddings, just to get through the ranks.

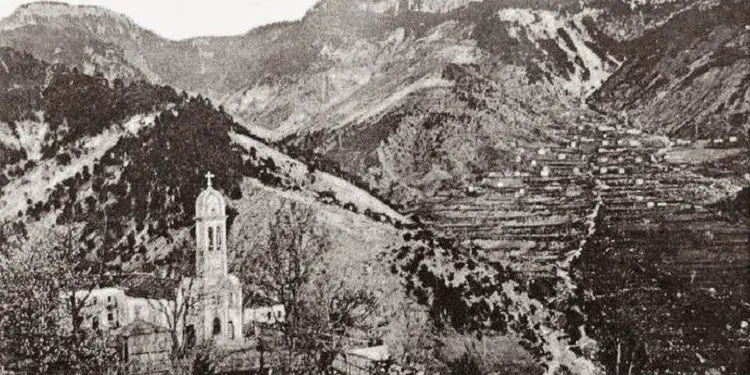

After the War, he served in the army in Himara and other areas of the Coast for three years, wearing the military uniform of a sergeant or captain, which suited him; he had been as far as Shkodra and Tirana, and perhaps, when he was young, before the borders were closed, and towards Kosovo. Orphaned at the age of 13 in 1936, his father Deda, who had been a tower builder in Dheu e Dibrrit-Mirditë, had entrusted him with the burden of “carrying” the house from Rrasa e Zezë, to Qafë-Vorrëz, after the three-story tower on the hill there on the banks of Lumagjini had “sunk” into the ground, something that would hardly have happened anywhere else. Here, then, lies his merit, which can be called an unwritten deed, like all the unwritten paternal deeds of this world, which have kept their house alive with the stove burning and the smoke rising.

It was not just about getting the roof on top with tiles, but the house was first and foremost a home, a living thing, a mill, a bazaar, going out to the village and the village, existence and survival. All of this could be summed up in the phrase: Guri i Caranit. Or the house of plang e shtëpi. If we were to venture into the ethnological realm, in today’s terms, the house was an institution that had its own head, the owner of the house, whose name was engraved on its gate and who was called by name in the yard by both known and unknown people: “O Marka Deda: O God of the House”!

In the conditions that my father found himself in, after the “apocalyptic” collapse of the Tower, it fell to him to rebuild everything domestically from scratch. He opened up with his own hands all the new lands in the new settlement, Livadhi i Karricas, bought by his grandfather, to make it productive and livable. He uprooted so many oak roots, to plant corn and vines that only a tractor could have managed. And, well, he was not a Hercules with a strong physique, but quite agile, as if the wind could push him along. Unlike the sturdy figure and solitary temperament of Nika from Martin Camaj’s novel “The Torches of the Night,” he was closely connected to his land, but like one, like the other, they never found an end to their eternal toil with the plow, to make the mountains fertile, as well as the fields, which could not be made so with the Party’s slogans, but remained barren without their strong wings.

We often went with my father to the Great Stream, through the groves of oaks, oaks and aspen, which had their source at the top of Lumagjini, some three thousand meters from the house. We would follow the water, as the stream sometimes broke at the collapse (which was a scary cliff, if your foot slipped, you would end up in the abyss in the stream), or in a couple of small ravines, sometimes the stream would fill with mud and the water would flow sideways. In winter, the stream almost did not bring water, while in spring all the men of the neighborhood would gather and open it to get it ready for the summer season.

It was said that the Great Stream was opened for payment by some Italian soldiers, who had been there, during the First World War. Its only work of art can be called the Laku i Pré, through which water passed from one side of a hill to the other. It is not known whether there were any technicians or engineers among those soldiers, however the line, as a difficult water supply facility, testified to the Italian experience.

With my father we would also go to the two mills of our old house in Rrasa e Zezë, “Mullini i Madh” and “Mullini i Vogël” where residents from Shëngjergji, Kalori and Bukmira ground the reeds. We would talk about every day, moral things, regarding family, village society and friends of the house, education, etc. That was our world at that time, in my childhood. Then came the probes, geology and mining with its workshop, the road-bridge, the forestry sector, etc.

Until 1973, the white-haired grandmother Dilë was still alive, who sometimes seemed to me to have emerged from the world of myths and legends, sometimes from the chronicle of the wars for Independence, who had stuck the cannons in “Boka e Dryshkut” and shot the enemy. Like every Mother and Son, the two of them complemented each other in beauty. In our family, no one ever spoke ill of anyone, so we children, thanks to the education that we had received from the elders, we knew nothing bad about anyone around us.

My father was humane, smiling, and generous; I had never heard him say “I”. This was even a style of mountain men, who would put their wise sayings into someone else’s mouth, for example, “as an old man from over there, near Oroshi or Kashnjeti, once said”, which is why their weighty words held sway. In other words, my father was not a man of the nation, nor even of the Province, in the sense of being a leader of the country, he never even had the stamp of the village.

The cooperative ruined the oasis he had created for twenty years with his own hands, he initially refused to enter the village community with this name, but after some political pressure, he joined. In the geology and mining where he later worked, he would throw a glass of wine with his friends, but he didn’t overdo it. He loved people and tried to do as much as he could for them. He never spoke ill of anyone and above all he never hated. He had no enemies, only friends.

I can say that my father was important to us as a family, as a model homeowner, who rebuilt our house from the “ashes”, with walls and fences, various trees, gardens – including a tobacco garden, fields with grapes, livestock, beehives, and above all, that he was a man. There is no word, more magnificent, more beautiful, and more remarkable than that. Memorie.al