By Kristaq Jorgo

Part One

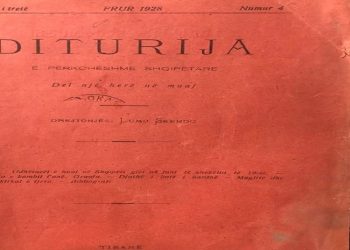

Memorie.al / Over the years, not only has Konica’s complex figure and personality been a topic of debate, but also his creative work. A case in point is “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” a work considered to have been left unfinished by the great thinker. The following article is an attempt to prove the opposite. The first biographer of Faik Konica, Qerim M. Panariti, would write in 1957: “His most powerful work is undoubtedly the novel ‘Dr. Gjilpëra,’ which uncovers the roots of the Mamurras drama,” in which he performs a merciless anatomy of Albania’s social and economic diseases. This satirical work began as a series of articles in “Dielli” in 1924, but it was interrupted after Konica aligned himself with Zog.

In this assessment by Panariti, in all likelihood, lie the roots of the claim, which continues uninterrupted and is reinforced for half a century to this day, that “Dr. Gjëlpëra” is an unfinished work. It has not only always been labeled as unfinished, but in some cases as only just begun, as it supposedly sets out to reveal the roots of the Mamurras drama, while in the fragment we know, this drama has not even begun to be mentioned.

Interrupted “due to Konica’s political shift to Zog’s side,” “Dr. Gjëlpëra” has been judged as one of the most convincing proofs of his “opportunism” and “inconsistency.” The interruption of “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” which everyone values as Konica’s literary masterpiece, has weighed most heavily in the almost unanimous judgment that Konica “has not left us a single finished work,” a consequence of his “lack of will” and “unwillingness to see things through to the end.”

The work’s incompleteness has its own weight in the disagreements regarding its genre classification: it has been described as satirical prose, long prose, an unfinished novel, a newly-begun novel, a novella, a satirical novella, an ethnological novella, something between a novel and a pamphlet. Due to this great disagreement, “Dr. Gjëlpëra” has never been given proper consideration in comprehensive studies on the evolution of genres and forms in Albanian literature.

In addition to claims of its undeniable value, a series of shortcomings have been underlined in “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” among which the “incompleteness” itself and those that stem from it are the main ones. It has been said that the work, more than unfinished, could be described as structurally fragmented; that the psychological motivation for the actions and the evolution of the character in the second part is weak, and in some cases entirely absent; that a series of fragments can be read as essayistic treatises on various issues, which have more to do with the author’s encyclopedic inspiration than with the work’s structure; that the connections between episodes are not very logical but are contrived by the author to enable the plot’s development; that the work lacks a complete artistic unity; that the second part has a fragmentary and anecdotal character, disproportions, and frequent repetitions of certain phrases by some characters; that by over-extending and scattering his narrative, Konica reaches a point where the subsequent continuation becomes so complicated and entangled that he forgets the promise to achieve the goal of its title, the uncovering of the roots of the Mamurras “drama,” and so on.

The disproportionately great importance carried in this case by an otherwise ordinary fact, such as the incompletion of a work, as well as the warning resonance of a remark by Lasgush Poradeci, according to whom, in the field of Albanian publications, it is not uncommon for “mistakes to be made again, and other mistakes to be added,” pushed us to undertake a research excursion into the roots of “Dr. Gjëlpëra.” We have reached some conclusions:

The publication of the work “Dr. Gjëlpëra, unveils the roots of the Mamurras drama” was not interrupted on December 24, 1924, as has always been said, or on the 20th, or even at all in December, or at the end of November! We can calmly maintain the momentum, in the issue dated November 1, 1924. It is true that at the end of the fragment of this date we will find the note “continues in a future issue,” but now we are at least completely certain that the interruption of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” did not happen when Konica “returned” with Zog.

The creation and publication of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” are as much a reaction against Zog, his clique, politics, and mentality, as it is a reaction against the post-June 20, 1924, situation; in fact, much more than that, a reaction against the general state of the Albanian world, and not just of that time: “Throughout all the events of recent times, where the conservative elements disappeared and our beloved bourgeois government came into power, we have listened with great care for a sign of general thoughts, for even a small understanding of the problems of the Renaissance of this people. But we listened in vain (“Dielli,” July 29, 1924, p. 5)”; “In Albania, only a cabinet change occurred, except that it was done with weapons: it is more a pronunciamento than a revolution. […] We are very far from a true revolution. (“Dielli,” August 2, 1924, p. 5)”; “Yes. There is no doubt that the politicians – the dark mob of people who use politics not as a path but as a goal – have begun to put a pickaxe to Albania.” (“Dielli,” November 11, 1924, p. 5); “That Albanians, in every step of political and social life, are drawn to details and never to general thoughts; and on the other hand, that Albanians think that every change is progress: – these are two facts that all observers of developments in the last four years must have noticed.” (“Dielli,” November 11, 1924, p. 5)

We can call the publication of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” interrupted, but we have no right to consider the work unfinished. In the “Dielli” of July 29, this editorial note is published: “Doctor Gjëlpëra unveils the roots of the Mamurras drama.” With the above title, Faik Konica, three months earlier, wrote a fable, which he then did not see the need to publish. Some ‘Vatrans’ who saw it advised him again and again to give it to the press. Mr. Konica decided to please those ‘Vatrans’ and will begin to publish the fable in a future issue of Dielli.” (“Dielli,” July 29, 1924, p. 8).

According to this note, it appears that the work was finished around the end of April 1924. The Mamurras event, the murder of the American tourists, Robert Lewis and George B. De Long, occurred on April 6, 1924. “Dielli” gives the first note on April 8, while Konica publishes his first article in the long series of articles on the Mamurras drama on April 16 (The Mamurras Drama and the Albanian Government). It follows that “Dr. Gjëlpëra” must have been conceived and written in a time frame of two to three weeks.

Konica – this conclusion is a direct consequence of the above – did not publish the fragments of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” “under the pressure of a periodical’s rotary press,” as has been said. On the contrary, the work began to be published after being finished. Well-finished, but to what extent? Since Konica, in the 70-90 pages that we know, “has not yet entered the topic,” he has not even once mentioned “the Mamurras drama.”

Under these conditions, we have two possible choices: either to assume that in just 15-20 days, Konica wrote, let’s say, 150 or 200 pages, at the very least, or to accept that something about the Mamurras drama doesn’t add up. The first possibility predicts an unimaginable speed record for writing in Konica’s case: “[…] the care that Faik bey Konica devoted to writing his articles and his characteristic slowness caused his magazine to always be published very late. In 1904, only the issues from 1902 were published, and in 1907, the issues from 1904 were published regularly.” – Apollinaire reminds us, among others. It remains then to accept the second possibility: that something about the Mamurras drama doesn’t add up. In truth, many things about the Mamurras drama don’t add up. And here we come to the fifth conclusion of the research: “Dr. Gjëlpëra unveils the roots of the Mamurras drama” has nothing to do with the Mamurras drama. We are listing a series of arguments in support of this hypothesis:

First Argument: The above-formulated claim seems absurd; as doesn’t the title promise only an illumination of the Mamurras drama? Of course not. The title promises the illumination of the roots of the drama. And the roots, in the primary and transferred meanings of the word, always come in time before the trunk, the branches, and even more so the fruits, whether these are sweet or sour – comedy, or poisonous – tragedy, or bitter – drama. We are therefore in the time of the roots; the events take place in them, and Konica promises to deal and does deal with them.

Second Argument: A feature of the work’s narratological organization has not attracted the attention of scholars: in “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” the beginning of the plot is the end of the fable. The work thus begins with anticipation, with the drawing of the almost idyllic tableau of “Dr. Gjëlpëra’s” completed house and his almost excellent relationship with the locals. What conclusion would be drawn? Some link of the fable might be missing, but the narratological stratagem assures us that no tragedy or drama could have occurred.

Third Argument: Konica mocks those who, raised and nurtured in the midst of the dominant mythical mentality in the Albania of his time, deal with the symptom, the consequence, the sign. And he calls for healing to come, on the contrary, by treating the disease, the cause, the real, through reason and the means it has produced. How could Konica make the capital blunder (to deal with a symptom, like the “famous” Mamurras drama), precisely in the work dedicated to satirizing that very blunder?!

Fourth Argument: The way the work ends is in full agreement with its structural matrix, which could be formulated as a clash of two worlds: the world of functional differentiation of post-Enlightenment European society, with the Albanian world, a synthesis of the world of segmental differentiation that dominated in archaic societies with the world of social stratification, which is typical of the European Middle Ages. The work ends with the very long scene of the visit that Dr. Emrullahu and Dr. Protagoras Dhalla pay to Dr. Gjëlpëra. Not only does this scene, at first glance, not end, but its last sequence doesn’t end either, not even the last micro-sequence of the last sequence. The work closes with a question uttered by Dr. Gjëlpëra: “But who can say that that boy of the people was not inspired by a hidden voice of nature?”

We are dealing, therefore, at least from a formal point of view, with a triple incompletion: of the scene, of the sequence, of the micro-sequence. But this is a seeming incompletion, just as the last sentence is a seeming question. The work closes with a rhetorical question from Dr. Gjëlpëra, left unanswered, a small but symbolic sign of his triumph over the representatives of the opposing world. How could a work that thematizes the dramatic clash of two worlds so fundamentally different from each other end differently and better? Undoubtedly, in this way with “a slow but sure progress” – a Konica syntagm – of the new world over the old world.

Fifth Argument: The publicistic hypertextual surrounding of the work, almost in the modern sense of this term – dozens of Konica’s articles devoted precisely to the Mamurras drama, published in “Dielli” and almost at the same time as “Dr. Gjëlpëra” – “disable” the literary work from treating the same thing and in the same way, due to its specificity and the necessary need for self-identification against the background of the hypertext.

Claims of the type: “Dr. Gjëlpëra is a literary work written with the aim of uncovering who killed the two American tourists in Mamurras,” demonstrate a dramatic misunderstanding of the nature of a work of art. The Mamurras drama is a real event, not a fictional event. Since when is the function of fiction to shed light on how reality actually happened?

Sixth Argument: The idea that Konica is not concerned so much and primarily with the Mamurras murder, but mainly and above all with the “mechanism” that produced it, is expressed repeatedly in his writings. From these writings, the impossibility for him to be able to concentrate his creative energies on the Mamurras drama or “ambush” in itself is almost explicitly formulated:

“If, since 1913, when Albania became independent, if at least since the Congress of Lushnja onwards, all the so-called “progressive” elements had carried out a fervent and tireless propaganda to awaken the conscience of the people, to spread among the people the feeling of respect for human life and the understanding of the vileness of bloodshed, then either the Mamurras ambush would perhaps not have been set, or the voice of the new conscience would have made the criminals’ hands tremble. Such propaganda has not only not been carried out, but from the entire development of history in the last ten years, a strange lesson has flowed to the people: that murder is bravery, and that bravery brings honor, profit, and elevation. Our ‘patriots’ like to see a progressive Albania; but their thought seems to be that progress cannot be made without ‘clearing away’ with a revolver the bad people, who are naturally the people who think differently. From this point of view, the brain of the Mamurras murderers and the brain of the ‘patriots’ are on the same level: for one brain as for the other, murder is an honest means. As long as this dark mentality remains unchanged, Albania will remain an African island in the middle of Europe.” (“Dielli,” December 18, 1924, p. 4)

Seventh and Final Argument: It relates to the ratio of event time to narrative time. In more than three-quarters of the text, events that occurred in a time segment of no more than a few weeks in 1920 are described. With this ratio between event time and narrative time and with this pace, how long would it take the narrator of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” to reach April 1924? / Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue