By Dom Zef Simoni

Part four

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, entitled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990”, where the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodër, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated as Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study, starting from the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to separate the Catholic Church from the Vatican, initially by preventing the return to Albania of the Apostolic Delegate, Archbishop Leone G.B. Nigris, after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and subsequently with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushi, who firmly opposed Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

Continued from the previous issue

The Great Prison of Shkodër

One day, around November 1950, at 12:00 PM, the head of education, Muhamet Uruçi, originally from Podgorica, called me to his office in the prefecture to tell me: “Zef, we will set up an anti-illiteracy course in the political prison. Three teachers have been assigned. You are one of them. The Authority trusts you.” I, the poor one, had open doors. They thought they owned me. This news came unexpectedly. I couldn’t possibly like going to teach in that place. I worried that someone might think badly of me. But I was completely pure, truly pure. This teaching in the political prison of Shkodër would last two years.

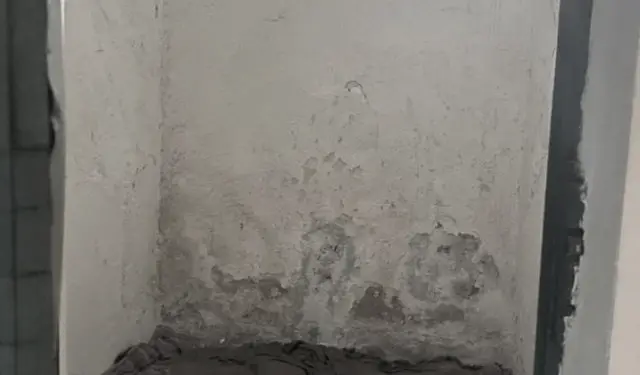

The Shkodër prison, as a building, came after the prefecture: two extreme buildings. The prefecture was beautiful, while the prison was a building that saddened and now terrified the city, even though it was on its outskirts. A watchtower was always visible, as was the guard at the entrance. That somber building had housed ordinary criminals, one after the other: those who had stolen, wounded, killed, who had committed crimes. The color of that building, always with a certain whiteness, gave off a bad light, more so during the day than at night, because even the sun’s rays, which are sometimes very longed for at night, and on a day with heavy rain, this building looked like a large grave where the bones had risen to the surface. After the first door of the prison was opened, one entered the courtyard and went towards the next iron door. Then I would emerge onto the cement veranda, which had a central arch, and you would find yourself in front of this building, with rooms that were almost all large. I entered carefully, after the guards thoroughly checked me. One of the first slogans this authority had been: “Trust and verify,” said by Great Stalin. It was called the Great Prison of Shkodër, because there were also smaller prisons, and it was filled with political prisoners.

All the prisoners inside this building had a slight white color. They looked like spoiled lemons. Many knew me and I knew them. I also had my school friends there. A select part of the city, the plains, and the mountains was inside. There were intellectuals, students, merchants, bajraktars (chieftains), officers, lawyers, professors, from the early years of the regime. Downstairs in one room were grouped priests. There were about thirty highlanders and villagers, who could neither read nor write, in this room. With these, I would work. There was no special room. I gave the lesson in the large room which had the number 9. A heavy and warm smell came into the room even in winter, because nearly 200 people were breathing in the room, and I could barely pass to get to the end wall, because people were tightly pressed against each other, lying on rags and boards. The small windows with bars did not allow you to see even a piece of the sky. Thus, you see neither sun, nor moon, nor stars, nor clouds.

“Here,” he told me, “is your workplace.” I was at the end wall where a blackboard was quickly placed. These highlanders and villagers, who lacked education, not intelligence, were given notebooks, pencils, a primer, and an arithmetic book, which on the first pages had the face of the leader, who was made to enter everywhere an internal prison guard, an ignorant and very arrogant policeman – as they all were – told them to learn well. “The past regimes have left you behind, in darkness. And from these you have come here. The People’s Power cares for you; it has brought you the teacher as well.” Teaching was given here three times a week, in the afternoon, about an hour and a half of lessons, an hour of Albanian language and an hour of arithmetic. When I left, the prison seemed a part of the city and the city a part of it. They were on the same line, but now the prison had become magnificent and more powerful than a castle. Here were the hearts of lions, dwelling in the most prominent building, after the sanctuaries.

Literature and the “New Man”

I was a teacher in several schools. I began to know the children, the parents, and the city. The People’s Power worked hard for education. It built new schools, good desks for classes, sent teaching aids, compiled textbooks, and schools with laboratories. Educational life had gained momentum, and this was for the formation of the “new man,” and for the destruction of the true man. Material bases against the spiritual and the intellectual. Only one foreign language was taught. In the first years of the regime, Serbo-Croatian, and after the break with Tito, only Russian remained for all the years of darkness. The other languages, according to the regime, belonged to the reactionaries.

As a literature teacher in the seven-year day and night school with workers, employees, and military personnel, and after completing the Higher Institute for Language and Literature by correspondence, also in the Commercial High School, I needed to know literature, more and more. Marxist interpretations had not influenced me negatively. They had not entered me. My strong inclination against these lessons was enough to prevent me from accepting anything. Providence watched over me.

My Readings

At a young, still childish age, around 13, I was devoted to reading. I went to the city library, a small, round building, in a flower garden opposite the “Big Cafe.” There I read ‘Pinocchio’ in Albanian, so beautifully translated by Cuk Simoni. We also worked on this book at school in Italian. There I read the book ‘Heart’ by De Amicis, ‘Rose of Tannenburg’, ‘Genovefa of Brabant’, ‘The Blind Musician’, and many other books very dear to our age. I read in every season.

For more than ten years, uninterruptedly, I read world literature, followed by classical Greco-Roman literature, several works of which had been translated into Albanian. From that of various Italian and French countries, a little German, but definitely Schiller, Goethe, Heine, and in Spanish, Lope de Vega and the special writer of all time, Cervantes, with his ‘Don Quixote’, which I explained with passion in the Commercial High School. From Russian literature shone Pushkin, Lermontov, Turgenev, and as a Christian peak, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, who was forbidden.

Out of curiosity and for teaching purposes, I needed to know Soviet literature, a decadence of literature, as was socialist literature in Albania. Definitely Gorky’s ‘Mother’ and the long and distinguished novel by a writer with literary power, ‘Quiet Flows the Don,’ by Mikhail Sholokhov. Russian literature is to be loved and admired, among the worlds most selected, and I would never like the Soviet one. I was reading two great writers one after the other, and they were Victor Hugo and Alessandro Manzoni, belonging to the same century and the distinguished literary current of Romanticism. Without knowing that it was forbidden by the Church, I took up ‘Les Misérables’. Hugo elevates the Bishop with flaws who will bring Jean Valjean to the right path. I called ‘Les Misérables’ a mistaken beginning and not realistic. Manzoni criticizes Don Abbondio with pain and reason. Why did I think Hugo gave us the miserable in that form, and not the bad as Manzoni did? Hugo’s unfortunate characters will lead us to revolutions that in reality do more harm than good. I called the French Revolution miserable due to its goals and outcomes. Even later democracies became heavier than the Monarchies, with the faults of Kings and Princes.

We won’t deal with the Bolshevik Revolution. It is anti-human. All the crimes of revolutions, having blood and poison, have more elements of terror and violence, and they achieve some liberties that are more harmful than repressions. I was reading. It was a sunny day. Some white clouds drifted quietly. How beautiful they look in this month of May. And in June, even when they are harbingers of rain. I was reading ‘The Betrothed’ by Alessandro Manzoni, translated into Albanian by Father Mark Harapi S. J. The characters of the novel, Lucia and Lorenzo, have a rare beauty. Very elevated are Father Cristoforo and Federico Borromeo.

I read it in the spring months, during the day and moonlit nights, and waited impatiently to reach the end. And it was reached one day before the Feast of Pentecost, before the day when children would be dressed in white clothes for confirmation. Providence, which is the main idea of this work, is the work of the Holy Spirit. A very beautiful work is Chateaubriand’s ‘The Genius of Christianity’. And didn’t Dante analyze life and the world, the human spirit, and that the facts found in that trilogy are ordered, belonging to both time and eternity?

About the ‘Divine Comedy’, I also heard lessons at the Institute. Even materialists boast about dealing with this. It’s laughable. I laughed when they poked their noses into the afterlife they don’t accept. The lightest accusation that can be made against communists is that they are grandiose and stubborn. And the grandiose suffer more than the humble. The humble have no worries. I read many works by Balzac and the English playwright, Shakespeare, a distant brother to Aeschylus. Hamlet hurt my heart so much; he won’t kill the King when he is praying. He waits for another time, when he is in sin, when he loses his soul. The idea of murder with the loss of the soul is terrible.

Many thoughts came to me spontaneously, without needing to seek them. Some left and others came. It was like a coming and going of visitors. Work and feast in the brain. It was the time when many translations were being made into the Albanian language from the continents of the world. I read American works, from Jack London, Hemingway, from Latin American countries, and many others. I had work with Albanian literature. I read and studied it completely. I had gained theoretical knowledge about it, according to Marxist criteria, but slowly I subjected it to criticism, and I was able to form my own ideas.

The Turkish Stain of the Government

Literature began with the ‘Formula of Baptism’ by Archbishop Pal Engjëlli. What pleasure I had for those blessed times of Skanderbeg. Our old literature was religious and national, and sometimes artistic, with Buzuku, Budi, Bardhi, and Bogdani. They are the first early lights in our Albanian culture. The binomial “Faith and Homeland” was pure. In school, passages speaking of freedom against the Turk were developed. We could curse Turkey. Its strong remnants, no. The government was communist, but many of its elements had the Turkish stain. We had to curse the anti-popular regimes, led by King Zog, and even more so fascism. They would not mention the stanzas of the writer Pashko Vasa that spoke of God, in the Rilindja manifesto “To Enslaved Albania.” That line was important to them; “The faith of the Albanian is Albanianism.” They wanted Ndre Mjeda without Christianity. Samiu, Naimi, and Çajupi wrote about Albania, about Albanian life, with love and passion. But all of them led towards communism, because they had the spirit of freedom, without understanding in essence what sequences their Enlightenment freedoms brought.

From a literary standpoint, Naimi and Çajupi have some value in stanzas and poetry. And Samiu has good prose. But many of their ideas I did not like. They should not be liked. Samiu is a deist, Naimi, a pantheist. Çajupi is more of an atheist. They wrote well, for the homeland and for the Albanian language. But their currents have a disturbing spirit, as they lead towards materialism. There was a great propaganda against faith. Slogans were seen in the school corridors; “Religion is opium for the people.” Teachers told students that there is no God. This was done especially by those who were party members. Others who were older avoided it. I was resolute in my clear opinions, which even the state knew, because I went to church regularly.

Our great writers were labeled “reactionary.” They were removed from the list, and Fishta later even from the grave. And they were fought against, such as: Father Gjergj Fishta, Zef Skiroi, Faik Konica, Ernest Koliqi, and Monsignor Vinçenc Prennushi, who is known as a civic poet and a sweet and quiet prose writer. Even he was not accepted. I secretly read his translations: Sienkiewicz’s ‘Quo Vadis, Domine?’, Wiseman’s ‘Fabiola’, and Silvio Pellico’s ‘My Prisons’. Fan Noli is a good writer, in prose and poetry. ‘The History of Skanderbeg’ has a pleasant and arbëresh style. A first-rate translation of masterpieces, with a beauty to their introductions. The writer I singled out was Fishta, who gave us the environment, the reality of the nation, the Albanian psychology. For hundreds of years, he showed us who we are. Faik Konica, and Ernest Koliqi, with good materials, also gave this reality.

Asdreni and especially Lasgush Poradeci, is an artist in poetry. As for Migjeni, though not untalented, with those ideas against God and Heaven, I held him in disgust. I thought that man, from one perspective, being so small, almost nothing, to deny his Creator. We had reached the black epoch. Social degeneration was entering all parts. When I was teaching, Ismail Kadareja had not yet emerged. I followed his writings. He writes beautifully: the work ‘The Castle’ and ‘A Chronicle in Stone’ are captivating. And some others. Communism has its own ideas that are not natural. Whereas literature is natural. Communism has everything by force, and so, everything is artificial. Talents are not lacking even in this era, but they are forced and artificial, such as some of Kadareja’s works and Dritëro Agolli’s ‘Mother Albania’. The writers of the time and the beauties of nature, they want to link them to the beauties of cooperative life, which does not pay you and leaves you hungry, of the cooperative that is filled with theft, fear, injustice, and quarrels. Even the livestock suffer. A bad shadow falls on the plants and trees, growing poorly. Factory life is the same. Office life is of one kind, with officials who do no work. School life has neither ideal nor spirit. Family life is confusing and without blessing. Day and night with fear. The reactionaries feared arrests. You don’t think of looking at the sun, nor the moon, nor the panorama. We don’t know where the characters in these types of novels come from.

Let these remain a testimony of their lives and the follies of a confused and wicked time. Literature remains a force in art, and with good ideas, when it has them; it becomes beautiful in its consequences and powerful, because it permeates the minds and hearts of humanity through the centuries. I wondered when people appreciated a work that had style, but had harmful content. In that case, this writer succeeded in forming his slaves. The spirit and value of a work with style will be judged by its purity, by its purpose. Work was done in school. It was demanded that students benefit, but there were no real intellectual or spiritual opportunities to advance. The state demanded that many pass, with a high percentage. The social subjects were poor and full of distortions and deviations. Thus literature and history, in all classes and in all schools – seven-year schools, secondary schools, and universities – which began to open in Tirana and some cities of Albania, including Shkodër. Philosophy was not taught. Its place had been taken by dialectical and historical materialism.

The Albanian language, Albanology, the scientific subjects, and the lessons in vocational schools were better, with the exception of biochemistry. Darwinism was strictly taught. Eight-year schooling was mandatory, and there was discussion about secondary school as well. To attend higher education, the government’s differentiating policy was implemented; scholarships would be given to those who met the political conditions. Students of communist parents had precedence, and for others, enrollment was boiling with difference and political corruption. For the Catholic element, the doors of the universities were almost closed. They could benefit little in secondary subjects. The children of reactionaries, prisoners, and their close kin, however capable, were excluded a priori. Abilities and talents were not considered. Let the capable, the talented, finish, let them die, because they are de-classed. Albania progressed with generations of the incapable. Thus, going on a road, without a road, is worse than lagging behind.

Stages of Nationalization

The days passed not in silence, but in a heavy noise. People had something to deal with. Bread had to be earned by the majority. There was work, but where it was assigned. People were put into work competitions, because the norm was everywhere. Women and girls buzzed like bees in the factories, to exceed the norms, to earn something more. But this was dangerous for the workers, because “these” (this was the contemptuous word for the government) were ready to raise the norms, according to the revolutionary style. The poor male and female workers gained a few days of exceeding the norm, only to lose the entire year and years. Due to great need, they had not understood the wickedness of the regime, at their expense. In the first days, the State had launched the slogan: “We will build socialism with our forces, and then communism.”

Year after year, the nationalization of forests, lands, banks, factories, and schools began. In schools, the life of the country would be reflected, with social movements. The life of the working class and the main leader, Enver the tyrant, would become the idol of idols. After the nationalization of the lands, the Agrarian Reform was implemented, according to which the peasant received the desired land. Citizens who had owned land in nearby villages had their land taken away. The reform was good, and those who had many members in the village could take up to 60 dynym of land. The peasants thought paradise had descended. But soon the state began demanding taxes, which almost the majority was unable to pay. Among those families who were unable to pay, confiscations were made to take their cow, oxen, and the fruits of the land, but not the land itself.

This would happen gradually, later. After three years, collectivization began – a “beautiful term” – with forced will, leaving the peasant only three dynym, 20 sheep, or one cow, working from sunrise to sunset, about 16 hours a day. Workplaces were assigned by the victorious brigadier, according to a plan, caprice, interest, and his games. People worked in the cooperative, men and women, from 16 to 60 years old, with an income of 150 lek per day, and in some cooperatives, due to the harshness of the terrain, up to 30 lek, when one kg. of bread cost 20 lek. After 7-8 years, the merging of cooperatives was done, calling them higher-type cooperatives. Immediately, everywhere, the three-dynym land was removed, leaving only one dynym, 10 sheep, or one cow.

When the new invention, the “herding of livestock,” was made, peasants received 100 grams of milk per person, or even less. This caused the peasants to queue up in the city, to buy, with a fuss, milk or cheese. That milk, which would pass through different hands, adding water, from the milkmaid to the carter who distributed it, and even to the saleswoman, who kept the water jug under the counter. There was no peace, and people had found comfort in theft. Life could not be conceived without stealing. The large herds turned into micro-herds, and the peasant was not allowed to keep any livestock, except 9 chickens and 1 rooster, locked in a coop, like the Albanian population surrounded by wires, so as not to harm the blessed fields of the cooperative. Keeping pigs was not allowed, and many kept them secretly, and to avoid inspections, they got them drunk with raki so they wouldn’t make a sound, and placed them in bed so that during the inspection, they would think a sick person was there.

Theft, deceit, quarrels, envy – even brother against brother envy – work discrepancies with favoritism, self-interest, espionage, and corruption reigned everywhere. A society that was living with corruption. The weather was like a storm. When the wind blows, frost falls and ice forms, in this terrain that froze even the heart and in the cloudless sky, because life carried darkness with it. And “they” called obscurantism everything that was not theirs. When occupation armies passed through a country, their steps carried the heavy weight of slavery. No occupation is heavier than that of a system where people fight against each other, and worse, when a clique puts its heel on the masses and the good people. The clique gradually occupied the country and subdued it with tactics. Why shouldn’t one be interested in life? This passed through me at home, at school, in the library, in church. I stayed away from evil, although I had my weaknesses. I was not a person without the grace of God, and when I stumbled, perhaps without true intention, oh, I, a sinner, never went to sleep with sin in my heart.

I wanted to go towards the good. I had respect for people, for children, and especially for women. Respect for them was also like an ideal. An ideal that also brought me pain. In some good and wise conversation with them, especially with relatives, they would say that by nature we are subdued. We live under the prejudices of men. We are somewhat afraid. We take control late. We are always in danger. There are men who know how to behave with women. But even when we are good, we must be strongly careful to protect ourselves in everything because bad is easily thought of us. Therefore, we must live intelligently. Therefore, I felt pain, because the woman considers herself an unfortunate being. I formed my opinion about the Albanian woman later. She is wise, graceful, and intelligent. She is busy with work, subtle in faith, constant in prayer, and understanding. I heard from women that those who do not believe are like the dull. Women give importance to everything and have the power to put you on the right path.

When they are not good, they put you on the great road with caprices, with refined forms, with wickedness. The man is sometimes unpolished and only has broad-heartedness and tact. I did not dare to start a family, I had hesitation, and something hidden was holding me back, stopping me. Thoughts crossed my mind. I had sympathy, but no connection. I was always occupied with readings, but these were a pastime for me. And finally, I read a book. This somehow increased knowledge. Nothing more. Little joy for me was when I woke up in the morning. To eat little. To go to school. To teach. I gave grammar with pleasure. Also literature classes. They were knowledge. I also taught history and geography. But, what is the work for? It is thought to mechanize.

I met a school friend of mine, also a teacher. We were on the benches of the flower garden, before a beautiful sunset. Sun and a few red clouds. I told him: “The monotonous life bored us, tired us. People must change. This world must be different.” He cut it short. He had solved the problem this way: “The world doesn’t change. People don’t change. It always goes like this.” I didn’t agree with him. We remained like two friends: he was unmoving, while I was not, because I had work with my own front and my high activity. I always wanted to move. Something great was bothering me. I thought everyone has a spiritual world. So I wasn’t satisfied either.

The Illness of 1949

I fell ill with a severe illness, typhoid fever. I was hospitalized. My father had seen me when they lowered me on a stretcher, from the observation room to the infectious diseases ward. He was saddened and cried. A very troubling event for the family. The whole family came to ask every day, several times a day. Every day, the whole family prayed, going also to the Church of Our Lady, near the castle. They brought me food every day, compote, and especially grape juice, because the illness struck me towards the end of August 1949, full of bitter Albanian events, with the provocations called “of the Greek monarcho-fascists,” with “diversionists” near Mirdita, with the murder of Bardhok Biba, with bloodshed and revenge. I was unable to read the newspaper or listen to the radio, which was in the corridor.

The infectious diseases room had a beautiful position on the first floor and had two large windows, through which the sun’s rays entered quietly as if at home, and stayed with us for a good hour before sunset. There were five people in the room, and one had died a few days earlier, from severe typhoid in the head. Sister Virgjina of the hospital, who was truly a hospital sister, still strong, may she be blessed, was a comfort to all who rested there. Our food was milk during the day and yogurt in the evening. Every afternoon the sister brought us large hyacinths with clusters of well-ripened grapes. We each took our ration. The ration is truly an invention of crisis, but it is characteristic of the modern era. The sister knew me, my mother, and my father. Everyone in the room was Muslim, except me. One person was sick and had little help from the family. What was left over, the sister took to him. “Don’t feel bad,” she told me privately, “because I take it to him. Your mother and father bring yours.” I felt very good about her action, but for a few moments, I thought that I couldn’t last long, this world is complicated and has evil at its root, and the sister had to justify herself before me. Day by day, I was improving until I recovered. The disease left me with a slight disorder of the nervous system. Some ideas I had disappeared. This continued for a while, with physical exhaustion. After a month of convalescence, I went to school to teach. The school was called “Vasil Shanto,” and it was where the Franciscan primary school had been before, and we had had the “Antoniana” society: O tempora, o mores!

After a few days, I started to somewhat renew my thoughts. I started writing social themes contrary to the regime. This gave me pleasure. I had great comfort when I went to church. I went mostly to the Franciscan Church of Gjuhadol, to see the afternoon mass, and to the Cathedral Church, to see the exposition of the Eucharist. All that effort, that work that was done with me in the family, at school, and in the church, had done its part. But I needed clarity for my mind to rest. I sought peace. The ideas of the time were the worst. The thoughts of many scholars were insufficient, because many of them have earthly ideas. Earthly ideas have earthly values. The sermons given in church spoke of elevation, but I could never be satisfied with little. I wanted everything in detail, everything clear, I needed subjects with knowledge and spiritual power. You would take someone’s example. There was talk of Christianity, of its work, but one needed to enter the spirit of Christ and his doctrine. For me, this meant removing clouds, gloom, entering the interior. The darkness that can afflict us, and which often brings sadness, can also make us futile. Completely futile. We cannot start building something truly spiritual; we cannot succeed without having knowledge and the ordered connection of truths. Ideas came to me sometimes unexpectedly, and one of these was what theology is. But this was impossible for me. Since I also spent a good amount of time in the city library, I was chosen as a member of its commission. I was one of the ten who were appointed. Thus, I could also enter the room of forbidden books, which were not allowed for public reading. Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)