Taisa Pisha (Batkina)

Second part

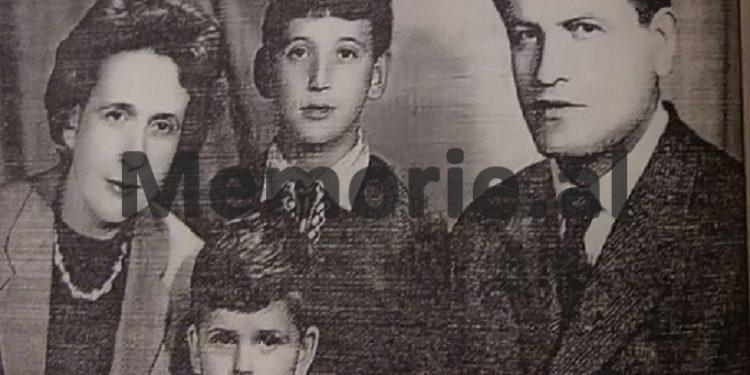

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was orphaned at a very young age, after her father lost his life during working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with great difficulty economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, who had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, where they began life in the city of Tirana, Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- Leninism, where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkin on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to ten years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forgets what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

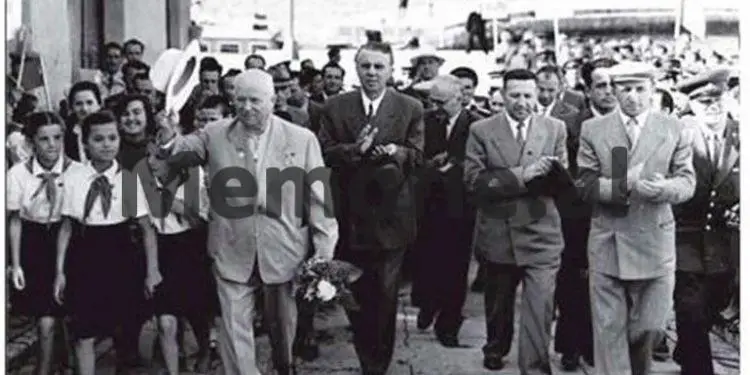

We were not allowed in the club where the embassy staff and Soviet specialists working in Albania gathered, not even to watch Russian films. I remember when I went there to see the American movie “War and Peace”. I entered the hall after the movie had started and left quickly in the dark, before it was over. The specialists were strictly ordered not to associate with us, although most of them worked together and lived nearby. Whoever violated this order received a stern warning. For our children to study in the Soviet primary school in Tirana, it was out of the question. We were renegades, if not real traitors, immigrants anyway, something akin to white emigration. We demanded that the embassy change its attitude towards us and not call us traitors. When Khrushchev came to Albania in 1959, we decided to send him a letter with our complaints, addressed to the embassy, asking him for help so that the embassy would allow us to attend the club, to give us films to first, etc. After some time, they started to leave the club for us, one day a week to carry out our activities. However, we were not allowed to mingle with other Soviet nationals living and working in Albania.

The attitude of our embassy towards us changed after cracks were noticed in the Soviet-Albanian relations. Suddenly we got better, Consul Fadejev, started inviting us to the office, to participate in the drafting of work plans, to offer us films. Albanians were becoming enemies and we… friends! But Albanians also began to treat us differently. Thus, without even realizing how, from the day we got married, we became part of politics. It seems to be funny, but here we are just wives and mothers, we suddenly happened in the orbit of Enver Hoxha’s politics. But then we did not know all this. Everything came to light much later, when we were arrested and learned that our “file” had been opened, since the breakdown of diplomatic relations. Out of nowhere, we began to realize that the Soviet government did not even want to know about us, about our problems. These were especially proven after we fell into prison. Nothing, absolutely no step was taken by the Soviet government, to help us, to release us from prison, to make our lives a little easier. We were all USSR citizens, yet the letters of our relatives to the Soviet government fell on deaf ears. If only we did not exist!

But let’s go back to the 1960s-’61. Relations with the Soviet Union were deteriorating in our eyes, as we acted like ostriches, hiding our heads in the sand. Life became particularly difficult in 1961. Attitudes toward Soviet specialists changed, many left, many projects were cut in half, and planes flew almost empty. In the summer of 1961, Roza Koçi was deported, declared a “persona non grata”. She was the wife of Mandi Koçi (I will write about her later), philologist, translator, good connoisseur of the Albanian language, author of the first Albanian-Russian dictionary. Roza often went to the Soviet embassy, translated films, taught Albanian language. For this and he was expelled in the early ‘60s.

Meanwhile, the situation became extremely aggravated, started that atmosphere of fear which I cannot remove from my mind even today. The events rolled like an avalanche. The last groups of specialists, although long-term contracts had been signed, were called home. Students, military trainees were returning from Moscow. “Soviet women” also began to leave. From the outside everything looked good and beautiful. Nowhere, in the press or on the radio, was a word spoken against the Soviet Union. The trial against Admiral Teme Sejko, accused of espionage, in the service of Greece, was taking place in Albania. Soviet security knew the issue was fabricated. Khrushchev proposed that the issue be considered by members of the Warsaw Pact, but Enver Hoxha rejected the proposal. The process was open and this made the situation worse.

It seems to me that it is the place to shed light on the political situation of that time. In the late 1950s, ties between the countries of the socialist camp took on a new development; the Union of Mutual Economic Assistance was established, the Warsaw Pact was signed. In the framework of these agreements, the construction of many facilities began in Albania. Ties were also strengthened in the field of defense.

After Stalin’s death, as is well known, Khrushchev replaced all the leaders of the socialist camp countries, except Enver Hoxha. After the XX congress of the Communist Party of the USSR and the publication of Khrushchev’s famous letter, in which the cult of the individual Stalin was struck, the campaign against the cult of the individual began in other socialist countries. Moscow asked Enver Hoxha to support the decisions of the XX Congress, especially regarding the cult of the individual. But how could Enver criticize himself?! He was a savage tyrant, cunning, hypocrite, intriguer; he sensed the danger that threatened him before he appeared visibly. The path of his coming to power and the period of his stay in power, have been covered in blood. (Now in Albania, many materials have been published that reveal the bloody deeds of the Albanian communists, led by Enver Hoxha). Enver understood well that Khrushchev would do anything to remove him from power and replace him with his own loyal man. Of course, the disagreements between the two parties were not for the benefit of the general public, we could not even imagine them. At that time I was still not used to reading between the lines. Now I just write about the events I remember, without analyzing them. This is the job of politicians, historians, who can collect documents, facts.

In April 1959 Khrushchev came to visit Albania. Here they made solemn receptions. I too was among the crowd that welcomed him. In his short speech at the airport, Khrushchev said such a phrase: “We, as a good housewife, must remove the dust every day, so that we do not accumulate too much.” Then we did not seem to be impressed by this phrase which, as we later understood, concealed a deep meaning. Khrushchev’s stay in Albania passed with much fanfare. As a result, he waived all debts that Albania owed to the Soviet Union, donated the Palace of Culture, which would be built in the center of Tirana and many others, but Enver was more cunning than he. When Albania no longer owed debts to the Soviet Union, Enver Hoxha, taking advantage of the differences between the USSR and China, began to approach the latter. A delegation headed by Liri Belishova, secretary of the Central Committee of the ALP, left for China. But on his way home, Liriya was received by Khrushchev. As soon as he returned to Albania, he was declared an enemy of the people and exiled. At this time, Moscow’s real economic, political and diplomatic pressure on Albania began. We have always been surprised by the attitude of the Soviet Union towards Albania. There were many Soviet advisers in Albania, working in every field, from the top to the bottom. Did they not understand and could not inform, what is Albania and the Albanians, what was the Albanian mentality after 500 years, Ottoman rule, with a majority of the Muslim population, feudal relations until late, the hundred-year war with the invaders, the struggle to create state… all these, had left traces in the people. The ‘plum and carrot’ policy here did not drink water. Working in Albania, they should never forget that they were dealing with an oriental mentality. Khrushchev, on the other hand, was arrogant. In many ways, in relations with Albania, imperial arrogance prevailed.

At the XXII Congress, in October 1961, Khrushchev came out openly against the Albanian leadership. The Albanians reacted sharply. Words were followed by deeds, Moscow pressure continued. In early November, it was announced that the Soviet ambassador from Tirana had been summoned, and a week later that diplomatic relations had been severed. I remember our anxiety, the fear in October-December 1961. Every day, as we came to work, we asked each other about the news. I worked with a professor, whose wife and son had stayed in Moscow, many had friends or acquaintances, who were defending their postgraduate studies or who had gone for specialization, or were simply pursuing various scientific plans. Everything was falling apart. But we all hoped that the quarrel would remain only at the party level, and when word was heard that Khrushchev was seeking to sever diplomatic relations, we did not believe him. But that was true, a very bitter truth for me.

Period 1961-1966

Many years have passed since the time I am writing about. Many details are forgotten, but the feelings, the state of mind are not forgotten. We came to Albania and started a family here; here was my husband, my son, my house. To run away, to throw away everything, the husband, the children without a father, the father without children (I had a five-year-old son and I was expecting a second child). “How to do, how to act?” This question pierced my brain day and night, like a turret. The decision I was going to make was fortunate. At first my people sent me a telegram: “Come immediately”! Then the second: “Decide for yourself, think well, do not rush”! At home I was constantly in front of the teary eyes of my husband, who hugged and caressed Sasha. The mother-in-law was crying. We all rushed to the embassy. There they gave us exit visas for a few months and told us that we could act as we saw fit. But the embassy once again highlighted its “politicization”, if I may call it that. Some of us, whose husbands held important positions and made statements condemning the actions of the Soviet authorities, were not granted visas. The others were not given visas because they had not come out publicly to condemn the actions of the Albanians. Even today I cannot understand what they expected from us, ordinary women? Where to talk? (But after torturing the women for two weeks, they were given visas.)

I remember that I was also afraid that they would not give me a visa, but no… everything went well and I got the visa. I ordered the plane ticket, packed my bags, but when I imagined the horrible moment, of parting with Gaqo, of parting with the child, courage and determination betrayed me. And I still did not know how to do it. Many years after these events, among the letters that my mother carefully preserved, I found a letter I had sent with a friend, who had returned home. (We were very afraid to receive and give such letters; they also did a personal check at the customs and could tear up the visa). It was a letter of despair. I am bringing here some lines of that undated letter, although I remember that I sent it in December 1961… The embassy is leaving (you know this from the newspapers), we were given visas to enter the USSR, until February 8. In short, we still have a month and a half to think about. After this deadline I will not be able to come until the embassy returns. God knows when this can happen. When we leave here, the Albanian side writes in the passport that we are leaving forever. Understand? The possibility of returning is very small… I am leaving now, it is not known how long I will be separated from Gaqo, I will break up the family. (Maybe forever?) Children without a father! Is that a good thing? On the other hand, I was standing; it is not known for how long, I will see you… I am afraid that the Albanian side will force us… For now, they treat us very well… Of course, the newspapers should be read, but all should not be trusted… I, of course, am more to escape. Those who decided are happy. Most cannot decide… What about Gaqoja? … Oh God, how sorry I am for him! But to give up my homeland… I cannot decide about this ”!

We thought that we were only in danger of losing our Soviet citizenship, but we were facing such trials, that if we knew what fate would bring us, we would not think for a minute. The response from home was: “Decide for yourself, we approve of your every wish”. And we decided. Meanwhile, my husband, like many others, was summoned to the higher authorities and recommended that I not leave, that we not break up the family. “We cut ties with Khrushchev, not with the Soviet people.” Time showed that this had been merely demagoguery. I remember the feeling I experienced on the street when the procession of black embassy cars passing by the airport passed me. I was scared; it was as if I was being left at the mercy of fate and that I had to run away from there an hour ago. But I overcame this feeling, not to break up the family, not to leave the children without a father. Here I want to go back a little in time. After the war, with the arrival of the communists in power, the construction of a new life began in Albania. They needed cadres and many young people were sent to the Soviet Union or to the countries of popular democracies to study. Many of these boys met girls there, who loved them and sought to connect life with them.

However, in 1948, a decree was issued in the Soviet Union, according to which Soviet citizens were forbidden to marry foreigners, not only citizens of capitalist countries, but also those of the socialist camp. True love is proved by time. Many of my friends waited 2, 3, 4 years, even longer for marriage leave. In 1954, a year after Stalin’s death, this decree was repealed. That year and the following years, many girls came to Albania to be engaged and women to their husbands. This work continued and on the eve of 1961, the year of the severance of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, the number of “Soviet women” reached 300-400. Until 1961, we lived here normally, we were treated well, sheltered, helped to find work. Most of the women had higher education; some continued their studies at the University of Tirana, worked well, were honored at work, but also among acquaintances. After the embassy left, the “ebb” started. Those who could not establish good relations in the family, did not go with the husband’s people, could not get used to the new way of life, and left very quietly. And for those who had good families, it hurt in their souls to ruin their lives for life, to lose everything, so making a decision about their future was a very difficult problem. These fevers lasted for almost six months. Then it was impossible to escape. We should have had about 100 women left. The Albanian government, even in the best of times, did not allow our men to live in the Soviet Union, so we did not have the opportunity to choose our place of residence; we had to live only in Albania. And, of course, after the breakup, our men could not go abroad, with their families. /Memorie.al