By Bashkim Trenova

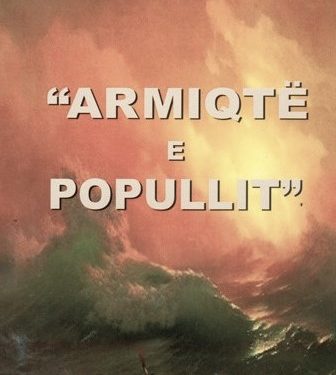

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, where he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office in the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was named in the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as Deputy Editor-in-Chief and then its Editor-in-Chief until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesman of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the period of the War, his childhood, the period of the faculty, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time where he had to get acquainted with some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their suckers, whom he described with rare skill in a book published in 2012 entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

With “Enemies of the People”

-Instead of entry-

On October 10, 1996, I presented my credentials to His Royal Highness, Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, an elegant, fragile man who seemed to have “planted” peace and kindness all his life.

I remember, the protocol required us to have a short face-to-face conversation. The conversation lasted, especially, about the period of communist dictatorship in Albania, about life and man under dictatorship. I showed as much as can be shown in a completely protocol meeting, where the minutes are counted and are part of the protocol.

I have been unforgettably impressed by the Grand Duke’s physiognomy, both immersed in a mystery as well as the extremely careful questions he asked me as I spoke to him. I told Him of a misery, which had crossed the boundaries of misery and which was furiously pushing an entire people towards non-existence. At the right moment, protocol opened the door to indicate that the meeting was over.

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg made a hand gesture as if to say “nothing, let us go a little further”! So, we went a little further. It was probably the first time that in this Palace the protocol was not strictly observed in the meeting with an ambassador!

Over the years I have always thought that to the Grand Duke my conversation seemed like a fairy tale from the past, like a stately legend coming from a non-existent world, a rival to hell, as credible as it is incredible.

In Tirana, the capital of my country of origin, Albania, I recently published a play for theater. Initially I had titled it “Absurdistan”, but then I named it “Cmenduristan”. I made this change because by chance, looking at the computer, I saw that this title had been used by an American author for one of his novels. At first I wanted to publish it in the West, in Belgium or in France, but it was not said.

“Absurdistan” or “Cmenduristan”, shows the extreme brutality of the communist dictatorship in Albania. I tried to stay as faithful to the times as possible and treated real people, real events and reports in the dome of communism as characters. I often put in their mouths sayings that they themselves had used and that I extracted from the archives of the time. I was surprised to learn that the West had a different logic and that this logic could neither understand nor accept, no longer as a reality, but even as absurd, the truth of our lives, not even a part of it.

For publishing houses and theaters in the West, “Absurdistan” went beyond the limits of the absurd, which is nevertheless understood and accepted as such. So the absurdity outside of reality was acceptable while the cruelty, tyranny of an absurd reality were completely inconceivable. With great courtesy, for example, the Paris Publishing House “Art & Comédie” wrote to me on December 6, 2008, about “Absurdistan”:

“This text is very well written, the topic is interesting and well treated, but I do not know how we can include it in our collections. Although we try to open our catalog to all forms of theater and thus to readers, it seems to me hasty to publish your text. “Thus, not seeing its reader, we prefer at the moment not to publish it.”

On September 29, 2009, the Brussels Theater “Transquinquennal”, to which the co-director of the “Varia” Theater in Brussels, Mrs. Sylvie Somen, had recommended to look at the possibility of staging “Absurdistan”, replied: it is nice, written in a Shakespearean-jarresk style … and it matches quite well what is expected of a piece with such a subject. “Undoubtedly, reality has transcended fiction, but we are unable to judge … a situation we do not know on the inside.”

After all they were right. By a fairly simple logic, a normal can never understand an abnormality, even though he is aware that the abnormality is not fiction.

Now, as I write these lines, I remember that my life passed down in that anvil of misery (for which I whispered a little to the Grand Duke of Luxembourg), pressed by the cruelty or tyranny of a dictatorship about which I wrote “Absurdistan”. I myself for years trusted and served her even more than a religious fanatic to his Lord, seeing in the executioner the savior angel.

Well, I lived near severed heads, surrounded by thousands of crippled lives, by millions hungry and ragged. I saw reality, but I thought he was sacrificing for a secure and happy future. This was promised sparingly in the slogans issued by the Congresses of the Labor Party (Communist), in the speeches of the dictator and in the press or propaganda of the Party.

Unfortunately, this “future” would never come. It took years to see clearly what was seen and what was hidden, what was said and what was not said. It has not been easy to realize and appreciate that: communism served us as a kind of powerful opium. We had to accept it, otherwise you would declare yourself a sworn enemy of your people and your country.

The rejection of a small dose of this “opium” was enough to put themselves in front of the firing squads, to be interned in concentration camps similar or even more unaffordable than those where the Nazis infiltrated the Jewish population and all their opponents. That was enough to end up in prison together with children and relatives, to wait there not for the end of the sentence, because there was never an end. Often you did not even have to wait for death, because it came commanded by those who had condemned you, by the true and only patrons of your life and death.

If the conversation with the Duke of Luxembourg had to be subject to the rules of protocol, then it should not have lasted, as far as I remember, more than 10-15 minutes, with my Belgian friends, Anne Gancberg and Mark Van den Dries, we talked over the years, occasionally, for my life and that of my friends during the dictatorship. It was these who pushed me to write these lines, as well as my wife, Desi, and my children, Bora and Arbëri, who asked me to leave them in my hands and in memory, a part of my life.

Childhood and early youth

Enver Muça is an old friend of mine. I will talk to you about it later. One day he sent me an e-mail where he wrote to me: “Somewhere I read that according to an American study, the day when it starts with good news (events, etc.) passes very well. As far as I can remember, you were either born in prison or you were a year old in prison. So you have “justified” the following years of your life. What about us deserters? We were born in “freedom”…! »

I was born in 1943 in Sevaster, Vlora. Sevaster is a mountain village in the South of Albania. There, one of the leaders of the Albanian anti-fascist guerrillas, Hysni Kapo, who would become after the war and until his death, one of the three central figures of Albanian politics, named me Bashkim. In the official registers, I appear as born in the capital, Tirana. So it was then. You did not register when you were born and then your parents or relatives declared the date and place of birth them.

I was the third and last child in the family. Actually, well, I was not born in prison, but my friend is somehow right. Without completing the year I was in jail. My mother was arrested by the Nazis while distributing aid to partisan families. I ended up in the cell with him. After the war, the prison building was turned into a school and there I attended my first lessons for several years. Even then, prison would “remind” me that it was part of my life. It is funny, but we high school students, in the last year we had to fill out a survey where, regardless of whether we were born or not during the Second World War, we were asked to answer questions such as: “Do you have participated in anti-fascist armed units “,” Were you arrested, imprisoned, interned by the Nazi-fascist occupiers “,” Did you cooperate with the Nazi-fascist occupiers or their treacherous collaborating organizations “, etc., etc.

I always replied: “I was imprisoned by the Nazi-fascist occupiers” and, when the explanation was required to be completed with the questions “when, where, how” ?, I then added: “Because of my mother’s anti-fascist activity”. In fact, my mother told me that I, without knowing it, was “activated” in the Anti-Fascist Movement! During the war she had illegally expelled Mihal Durin from the capital. For this they had paid a carriage where the three of us had ridden, my mother with me by the side and Mihal Duri as my father. Thus, Mihali, who would later be killed by the Nazis and declared, after the liberation of the country, ‘Hero of the People’, could pass before any possible fascist control as a regular family member. The testimony was my mother and me. Certainly I was not in prison for this anti-fascist “activity”.

I completed the same survey as the one in high school later when I started working. Also when I applied to be a member of the (Communist) Labor Party. In all these cases, over a period of many years, I have always given the same answer: “Yes, I was a prisoner.” The questions I had to answer seemed idiotic to me, but this idiocy also created the same humor for the absurdity it conveyed.

He was asked to give birth to a newborn or newborn during the war, to prove whether he was born “for” or “against” the government, or the political system established after the Second World War! What seemed illogical, however, was perfectly logical and vital to the functioning of the state apparatus. On such idiocies and absurdities would be based the Dantean mechanism that would be known as the “class war” and that would transform Albania into a giant Gulag of thought, body and soul. My friend who, unlike me, was born “in freedom” also writes about this prison.

I do not remember the Nazi prison. My mother, Ismete Peza, told me that there in the cell, she was placed with another anti-fascist friend, Ela Gjikondi, it seems to me that her name was. I was their only joy as they waited to penetrate some concentration camp in Germany, towards death. She owes her life, maybe even me, to the former prefect of Tirana at that time, Qazim Mulleti. He was in an old friendship with my grandfather, Shyqyri Peza. Both had been political opponents of former Albanian Prime Minister Ahmet Zog, who in December 1924 was forced to relinquish power and immigrate to Yugoslavia.

Both, Qazim Mulleti and my grandfather, Shyqyri Peza, had emigrated, one to Italy and the other to Greece, after Zog returned to power, who would later declare himself King of the Albanians. Both returned to Albania on the eve of the occupation of the country by fascist Italy or simultaneously with the occupier. Although in different political positions, they do not cut the bridges of communication between them. Qazim Mulleti, for the post he held, was well informed about the movement of fascist troops in Tirana and its surroundings. He, more than once, informed his grandfather about the preparation of military operations of the invaders in the region of Peza, where numerous partisan, anti-fascist forces were concentrated.

As my mother told me, Qazim Mulleti called him to his office and told him: “I will leave, the Germans will be angry with me. ”If you are caught one more time, your place is in Germany.” After being released from prison, the mother went underground and joined the partisan forces.

In the post-liberation years, a comedy entitled “The Prefect” was staged. Qazim Mulleti is cartooned in it. In fact, neither in time of peace nor in times of war are things always just black and white. Qazim Mulleti was indeed the prefect of the occupied capital, but I have also seen in the Central State Archive a letter with his writing to the German Command. The letter was written after German occupation troops had punished and shot innocent villagers in the Petrela region.

This they had done in retaliation for the losses they had suffered there in the struggle with the partisan forces. Qazim Mulleti distances himself from this action and even expresses the opinion that such operations against innocent people can be nothing but productive. In the memoirs of King Zogu I’s adjutant, published in recent years in the Albanian press, it is proven that Qazim Mulleti, during the War, helped Myslym Peza through his brother, my grandfather, Shyqyri Peza.

Myslym was affiliated with the Communist Party-led National Liberation Front. I do not undertake to rehabilitate or judge Qazim Mulleti. I am simply telling a truth from my life and repeating a witness of the time.

I would not have known about my mother’s imprisonment and release if she had not told me herself. My memories are of a few years later. After the end of the war, my father, Selim Trenova, also a former anti-fascist, partisan, was in charge of organizing the police in the city of Kavaja, and then in Durrës, the country’s main seaport, about 40 kilometers from the capital. We all moved to Durrës. At first we settled as tenants in an old two-story adobe house near the city center, at Aunt Kona. We lived on the ground floor.

From this time I can only remember the name of this good woman dressed entirely in black who cared for me “forgotten” by her parents engaged in their daily state affairs, just as I had been “forgotten” by them over the years of War.

In Durrës, as everywhere in Albania, at that time there were neither nurseries nor kindergartens for children. Aunt Kona kept me near her hearth so that I would not wander the streets of the city, under the balconies or shelters of unknown houses, near the canals where the mice of the coastal city did not fail to show their courage and fear. She, as I judge now, was an Orthodox believer.

Once in her house came an orthodox priest, who uttered some words incomprehensible to me and waved with his hands a pendulum or dome emitting smoke. At one point, the priest turned to me and looked at Aunt Kona to find out if she should include me in this ceremony or not !? Aunt Kona shook her head in denial. This, it seems, was for me the first incomprehensible lesson, which meant that people belong to different religions.

I, according to Aunt Kona, was a Muslim. My parents had never seen it, nor would they see the door to the mosque. For them religion was not a necessity. In this way I would continue in my life. Aunt Kona was right to exclude me from ecclesiastical blessing.

* * *

After leaving Aunt Kona, we settled in an apartment on the main boulevard of the city, which connected the center with the port, leaving next to a thousand-year-old castle. The apartment was part of a beautiful building with painted walls and two terraces that rose one above the other on its upper floor. The lower green terrace also served as a garden, where several benches were placed.

The upper terrace, smaller in size, rose several steps above the first. From its height you could see the whole city and the vast expanse of the Adriatic Sea, which separates Albania from Italy. In short, my parents, victorious returned from the mountains, poor, took refuge in a bourgeois house.

Here in this house I took the first lecture “us and them”, “the bourgeoisie and the working people”, “class war” and “enemy of the people”, certainly not with these definitions. The palace where we took refuge had been the property of a large merchant named Kosturi. At least that’s been on my mind since childhood. After the war, like any other property belonging to the rich, the Kostur building was nationalized or seized, and simple families, especially those who had taken part in or helped the anti-fascist resistance, entered it.

We settled on her second floor. As neighbors we had a family from the south of Albania, from the mountain Kurveleshi, a single woman, Saliheja, with four or five children and a goat. We became friends with them very quickly. Saliheja even gave me a second name, calling me “beef”. After many years, I have returned to Durrës once again. I climbed the stairs of the former apartment. I wanted to meet the beloved and compassionate Salihen. I was not sure if he still lived in the same apartment. Hesitantly I knocked on the door. It was opened by mother Saliheja, who just saw me, shouted “beef!” and she hugged me like her son.

In the palace where we took refuge, on the ground floor there were several entrances locked and locked. To me as a child this closure represented a real mystery. When I had to climb the unlit stairs alone to reach our apartment, I always hurried up the steps. With a feeling of fear I left the “mystery” as soon as possible. In fact, the “mystery” consisted of several warehouses in which all the seized goods of the Kosturi family were collected.

I knew nothing about Kostur himself. In my mind, there was even confusion between the name Kosturi and the Questura, the fascist police, and I could not find the connection between the latter and the confiscation of the goods or, more precisely, their locking up because I did not know confiscation as a term or as practice. Years would pass and I would get to know the “unknown”.

Coincidentally, after several decades, in the ‘80s of the last century, I made in the General Directorate of Archives of the Albanian State, a publication of documents for internal use. The documents included in this publication testify to the confiscation, sequestration and nationalization of movable and immovable

Property that was done to the former wealthy classes, the bourgeoisie, landowners and collaborators of the occupiers in 1945-1948.

During the search and selection of documents, I also got acquainted with the end of Kostur or more precisely of Idhomen Jovan (Cico) Kostur. He was executed on November 5, 1943 by the guerrilla unit of the city of Durrës as an accomplice of Nazism. In fact, he had been the chairman of the National Assembly, as it were of the quisling parliament during the Nazi occupation of Albania. According to the documents found in the Central Archive of the Albanian State, on June 21, 1947, his property was confiscated, a house with 20 rooms, other buildings and houses, land, gardens, a shop, etc. We, apparently, were housed in that 20-room house! In one of the houses confiscated from him, the police of the city of Durrës settled. After the fall of communism, the property was returned to its heirs. I do not know if in whole or in part, but I know that the state was forced to remove the police from the building where it was located to give it to the Kosturi family. /Memorie.al

Who is Bashkim Trenova?

Bashkim Trenova was born in 1943 in Tirana. After graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, he was appointed a journalist at Radio Tirana, in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked during the years 1966-1975. Later, during the years 1975-1983, he was a journalist and head of the Foreign Affairs Department of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’.

In the years 1984-1990 he passed as chairman of the Document Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives. After the first free elections in Albania (March 1991), he worked as deputy editor-in-chief and later as editor-in-chief of the newspaper Rilindja Demokratike. In the years 1994 -1995 he transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Press Director and Spokesperson of this Ministry. Then, until 1997, he is the Ambassador of Albania in the Kingdom of Belgium and in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

Bashkim Trenova has been a regular contributor to the newspaper ‘Drita’, a body of the League of Writers and Artists of Albania, where he has published translations of prose and poetry as well as critical literary and artistic articles. He has also made cultural reports for the Albanian Television as well as for the Kinostudio ‘Shqipëria e Re’.

Bashkim Trenova was decorated with the Gold Medal of the National Amateur Theater Festival and with the 1st Prize of the satirical magazine Hosteni. He co-authored in 1986 the documentary “Heroes of the National Liberation Anti-Fascist War”. He also published, in 1988, the documentary volume – ‘Nationalization of Private Property in 1945-1948’, an internal publication of the General Directorate of State Archives.

In 2009, Bashkim Trenova published the play part – ‘Cmenduristan’. In 2012 he published – ‘Enemies of the People’ (Memories) and ‘Heroes of the People’ (Reflections). He then published in 2014, the comedy ‘Vive les Morts’ (Long Live the Dead), in 2016, the comedy ‘Ubu Camarade’ (Comrade Ubu) and ‘La

Coupole Rouge’ (Red Dome – Reflections). In 2017, 2018 and 2019, he has also published the comedies ‘L’Amour à Louer’ (Love for Rent), ‘L’Ennemi-ami Strauss’ (Enemy-Friend Strauss), ‘L’Obsédé’ (The Fixed) and ‘La femme du mari battu’ (The wife of the beaten man). In 2020 he also published – The Diary of an Ambassador.

The next issue follows

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)