By Ahmet Bushati

Part forty-three

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Pjetër Saraçi was able to perform many humorous numbers, helped by the plasticity of his large face, with its flesh devoid of muscles and as if sagging, as well as by his two eyes that often became smaller, not looking at both at the same point, and also making his face take on the most deformed and ridiculous shapes, whenever he felt like it. He successfully imitated dissatisfied women, who complained in their thin voices to others, taking on poses those men usually did not find dignified, but which he did out of a desire to please others.

I remember an occasion when Pjetër was informed that his wife – out of turn – had come to meet him. Instead of hurrying up – as prisoners usually do in such cases – he was lingering, rummaging through his belongings in search of something, and, without caring at all about the time that passed or our words:

“Hurry up, Peter, you’re late!” and without even thinking that the policeman, out of impatience, might shorten the time of the meeting, which was always a few minutes. In the end, it turned out that he had been looking for a towel that had been mixed up in his belongings. After finding it, he slowly wrapped his head and face and, like a carnival of a bad woman, went out to meet his wife. I, in order to hear what he was saying to her, went behind him and put my ear to the door, which Peter had probably left slightly open on purpose. No man could contain his excitement when Pjetër Saraçi, in a spoiled, talkative woman’s voice, would say to his wife: “Who are you, my wife? What’s your name?” and then: “What’s wrong with you, my wife, that you love me?! Hey, what’s wrong with you? Why do you ask me…”, and other stories with which Pjetër Saraçi would fill the precious “minutes” of the meeting, which was once every two weeks?

Pjetër Saraçi would make up these and many others to please us, and after him, his wife when he had the chance. Simon Harapi would be one of those prisoners with whom I became friends since my early days. Prison, as a place of life and shared destinies, would eliminate many of the differences that exist between people, such as age, culture, origin, worldview, etc. Simon, a calm, measured and very orderly man in everything, would spend most of his time withdrawn in his solitude, and I had the impression that during that time, in addition to thinking about his family, he could also evoke a distant past of his youth, with the secrets that a pure and platonic lover of his head, who had confided in me.

Ragip Lohja, Hysen Lohja’s younger brother, also happened to be in this prison cell, but who at that time happened to be in a labor camp. Ragip had once represented Albania in Paris, in the hundred-meter sprint race. Shaqir Omari was also in that room, and they said he was very generous and that he enjoyed talking to everyone, regardless of age. Since he had spent his life in Malci, the Malcors must have found pleasure in that man in particular.

In the same room with us were several old postrribas, among whom was Isuf Hasani from Urës e Shtrenjtë, who was short and healthy in body, who was brave and loyal, and who was connected to some of the first houses in Shkodra. Isuf Hasani was very quiet and constantly in a good mood, and despite his age, as the oldest in that room, at the same time he would be so agile and physically capable that, like a true athlete, from a sitting position – cross-legged – he would throw them like a ball for several meters on the floor, without having to support himself with his hands underneath, and finally, he would take them to his feet, light them on fire and, without waiting a second, go in front of his fellow postrribas, – who were coming in a row one after the other – waving one hand and, as if nervously speaking: “You go now and do what I did”!

One of those postrribas who would like to be teased by Isuf Hasan would be another old man, Çelë Murati, who, at their head, had taken up a corner of the room. Çela, who was tall and slender and who was quiet, friendly and humorous, would find the opportunity with Isuf Hasan, without being seen by others, to remind his friends of “stories” from their long-ago youth, something for which Isuf Hasan was even more willing than Çela.

There was also Myrto Dani, the flag bearer of Drishti, a true and beloved babajaan like no other, who, as long as he talked to someone, would stand by him with a smile on his face. There was also Abdullah Sait, the son of the Rasek flag-bearer, Sait Duli, the hero of the “Postrriba Uprising”, a self-possessed and generous man, who was accompanied and helped by a Kosovar from Malcia in Gjakova, named Xheme Sadria, a true brave man, as those who had known him before would testify. There were also Nuz Halili, Dervish Nuzi and some other postrribas, while Hajdar Tafa, Muho Fetahu, Emin Zyberi, Selim Rraci, Shaban Hyseni, etc., etc., must have been among the other prison cells, not to mention other postrribas who happened to be in the Orman-Pojani camp at that time. Somewhere close to them was Abdulla Salihi from Puka.

A special number, not only for a prison cell, but for our prison, would be Jakë Gjoni from Juban. Jaku was very quiet and, as they say, “beaten with oil and vinegar”, the devil himself, but at the same time good and loyal, who enjoyed the sympathy of everyone, for the very interesting and special type he had. His presence alone would be enough for the other to start laughing prematurely, considering that he never left without having released one of his intelligent and original jokes, which would always make others laugh, which Jaku, if necessary, would also realize in rhyme. Jaku had no schooling, but his mouth rang out like that of a real orator, with talent!

If someone teased him, which Jaku liked as a pretext to get into a game, his improvised lines, always witty and humorous, sometimes even in verse and rhyme, would make a prison cell burst into laughter. If Jaku Gjoni had had an education, he would certainly have made a name for himself in the fields of humor and poetry, not excluding that of the stage. Jaku accepted anyone’s challenge and did not leave the “arena”, even if he was the last to speak. There were times when a poem was heard by someone else, Jaku would repeat it back without mistakes. Unschooled as he had been, just by listening to it, he had memorized the religious book “Genovefa e Berbantit”, which he would tell us to the end with full stops and commas.

He played “checkers” like a true master, but if he happened to lose, he would become very nervous and try to justify the loss in an unreasonable way. In such a case, they would hardly wait for Jaku to unleash on their backs all those who had shot nearby, and Jaku, for his part, ready and strong as always, would not retreat from the battlefield without having dealt with them all, one by one. Or was he not a saint! His mouth roared like an engine. Even his voice was as thin as a woman’s. Jaku ate a lot, more than anyone else there. He himself told how once, when the people of the house had charged him with the task of writing the fat of the horse, he had eaten so much of it that, as he himself said, he had seriously been bursting.

Jaku Gjoni had been in prison three times, for politics! He once told us: “Every time you passed the policemen and the policemen on the streets of Shkodra, you would look people in the eye, even if you didn’t know them, just to show them that you weren’t afraid.” Jakë Gjoni’s jokes are endless, but I’m telling you one more, as told by Jakë himself: “A very bad investigator was beating me bam-bum-e, bam-e-bum, without stopping at all. I was also beating myself up and not saying a word. Once that investigator got tired and bored and left that job with that. Then I asked him: Are you done? and he answered me: Yes, what’s wrong with you?! Then I said: Listen, I know what you want from me, and out of anger, I won’t show you at all”!

Good or not, but still a special type in that prison cell, there would also be a certain Gjush Pistolli, who never stopped talking, except when he slept and in whose heart fascism – even though it was out of fashion and despised by everyone – had left an unquenchable fire. Gjush would approach us young people in a friendly manner and, as if from a balcony, would call out several times in a loud voice: “Ei, ei, voi giovani”! Or from time to time, he would address us, waving his fist upwards and calling us with all enthusiasm: “Gioventú, gioventú”!

There were times when he would recite verses from the fascist youth anthem to us: “Youth, youth/ Primavera di bellezza”, and no matter how many times I told him: “Gjush, fascism everywhere in the world has ended once and for all, and we have fought it before, and if necessary, we will fight it again”. Yes, did Gjush hear these words of mine?! Not at all.

When he didn’t like it, he would pretend not to hear them and, in order not to spoil the fun, he would leave the path he had opened with us, walking away laughing. Although he was a somewhat “sfacciato” (brazen) guy and a convinced fascist, and as they said, maybe something else too, despite everything, at the same time, as a person, he was also lovable. Man Qeha’s return as a sick man from Orman Pojan’s camp at this time would have its own significance for us young people who found ourselves in a room with a lot of old men and sick men, no matter how good they were.

It was at this time that I was gaining health at a “gallop” pace, because I was eating a lot and with an appetite and also, from one day to the next, I was gaining strength. During the two hours a day that we played basketball with football goals, I never stopped moving and, with detachment, I was able to win most of the balls in the air even from the tall Gani Ymer and Paulin Pali, my opponents in the game, so much so that Gania would often get nervous with himself and with me, while Paulin, several times, would put his hands on his waist, saying in surprise: “How is it possible”?! It was during this period that I was also seriously working on improving my Italian.

One day, two prisoners of our age were brought into the room, and a place was made for them at the entrance to the room. We learned that they were from Mirdite. We, the younger ones, were among the first to go to meet them. One of them was called Ndue Fusha, who had a gentlemanly appearance, a noble and attractive appearance, although pale, like a galloping tuberculosis patient. His restrained and courageous attitude spoke of a boy with good qualities and from a prominent house in Mirdite. Just as good was the other, his friend as a brother, Gjon Marka Ndoj, with a very open and communicative nature. As very clever and close as he was to Ndoj, he was never separated from them, day or night, being his father, not only a brother, but also a sister, as he needed.

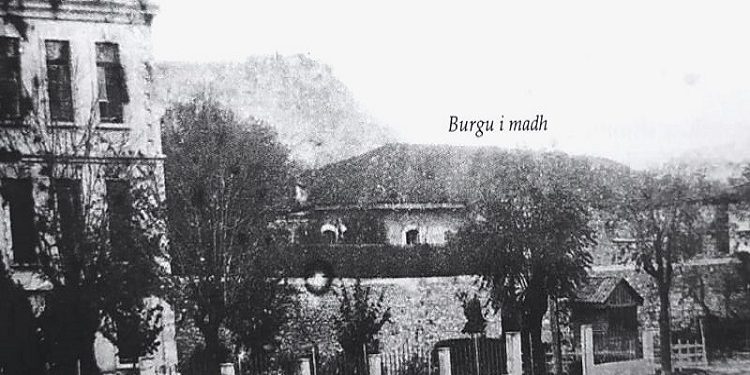

When Ndoj was sixteen years old, in 1945, he had already served a year in prison. On the occasion of the murder of Bardhok Biba, he had been arrested again and sentenced to death, but later saved from execution by the intervention of Bardhok Biba’s father. It would not be long before Ndoj, to the sorrow of all of us in a large prison in Shkodra, would die in room no. 3 for tuberculosis patients.

They had reported to me that I had moved from my room and one day for this, they took me upstairs to the director Shaban Haxhia, who only gave me a warning for the mistake I had made, and of course advised me not to repeat it. Another time, for the same “fault”, as it had been a repeated case, they changed my room, taking me to the one with no. 2, which, although it was raised by a flight of stairs or two and was paved with planks and had more air and light than that of No. 3, still my mind would linger on the room I had left, as I had been accustomed to being with it and its people.

In this room numbered 2, I would find Ernest Përdoda as my friend, who had been smoking heavily ever since, and who, to light it, would light it without the sun ever setting on the ground, and of course, without putting any water in his mouth, even though his face had been green since then. However, as a few days passed, I made some good friends in this room, above all, Hilmi Kamata, with whom I became strongly attached forever.

They had me placed between Bajram Xhemali with a hole-in-the-hole face, who was from Kalasë e Doda, – who until a few years ago had studied at the Tirana Madrasa and who also knew a little English – and Preng Bibes from Mirdita, a good man and quite misanthropic, but also very serious and talented, to produce miniature artistic objects from peach pits and celluloid. Once, as per my suggestion, from a black celluloid, he very delicately took out for me an Albanian with raised wings ready to fly, while with its beak, that Albanian tried to break the chains that had bound its legs. As a souvenir, I sent the Albanian with all its symbolism to Sime.

For about two months that I stayed in this room, with Bajram and Prenga, we would eat together, since, except for some very rare cases, no one would come to them. In the summer of 1951, when I happened to be in the labor camp over there near Peqin, Preka, together with Prel Toma from Nikçi in Malcia e Madhe and another friend of theirs from Dukagjini, had escaped from the “Big Prison” and gone to Yugoslavia. After a relatively long stay in the notorious camps of Yugoslavia, they were forever separated from their comrades and, Preka having ended up in America, would be recruited by the American military forces of the “Rapid Intervention”, and one day would finally find their death in the fighting in Vietnam.

I could not find peace within myself until I had discovered the person who had reported to me about the movement in the room, who one day could report others and even more important things. For this purpose, one day I decided to secretly go to room no. 3, where I had been before, and to stay there with a friend of mine, Tom Sheldon. While we were talking with Tom, I kept a constant eye on every movement that took place in the room. I was waiting for the person who had reported to me in the office two weeks earlier to move, and of course, I did not know who he was. Although he was late in moving, that person finally came, and I saw him when he – believing that Tom and I did not mind any movement from him – dodged towards the door of the room and slipped out like a thief.

In order not to be noticed by the others, he quickly returned to the room and sat down like an “angel” in his place next to the door. Toma told me to leave, since the goal had been achieved, and it didn’t seem enough to me until the police arrived, to prove to everyone that one of the prisoners was spying, which would only then give me a chance to expose him in front of the room. The policeman, for his part, had deliberately left me a little time, entered the room, and when he suddenly saw me, he turned to me, looking at me as if in surprise: “And you here? Come with me”! and took me straight to the prison director, who, for repeated violations of the regulations, would communicate to me the sentence of three days in prison. When the policeman escorted me through room 3 to the dungeon, I stopped in the middle of the room and exposed the spy in front of everyone, although over time it would be proven that he would not spy on anyone else and that he had done that to me out of the supposed need to justify the trust of the directorate, which, in turn, had appointed him as the room manager.

For us young people, who were for the first time in an environment of people of different ages, backgrounds and interests, we would be impressed by their general behavior, the respect and kind attitude they had for each other, their collective feeling and a nobility that perhaps was manifested by the majority there due to suffering. With each other, we would have had as the subject of our conversations several times the fact that the people there were so good, something we would not have believed before. In this not-so-large prison cell No. 2, I found old men who were respected by everyone, such as gentlemen Sheuqet Muka, Shyqyri beg Kopliku, and others of a younger age.

In this room also happened to be Xhelë Baci, who at that time was reading “Chef’s d’Oeuvres” from French literature and, when he really liked one of those selected novels, he wanted to read it to others. Xhelë was talented in literature, although he had done brilliantly in agronomy at Fultz’s school.

In that room also was the former revolutionary and disillusioned communist Gjeto Keqi, who would never abandon his humor of the countryside, who also read in French there and, as we have shown, who continued to manifest a poetic flair. He declared his friendship with me to be connected since the “neighborhood” of the dungeons that we had in the Sigurim, when, for every opposition I had to the interrogators, in a sign of solidarity with me, he would knock me against the wall with his fist several times. In that room, a certain Pretash Niket would be in charge.

I became friends with Todi Ruho, a Pogradec citizen, who was a gentle and sincere man who, among other things, would tell me how after the liberation, when a meeting of selected officers was held in Tirana, among whom was himself, on which occasion he had asked the question: “Now that we are so closely connected with Yugoslavia, what will be done with Kosovo?” and Enver Hoxha, who was formally leading that meeting, had answered: “Whoever wants the good of Kosovo, should wish that Kosovo remains with Yugoslavia, for the most favorable conditions that it will have for building socialism in its country.” In this room I also made friends with three Mirditas – who once, if I am not mistaken, had been students of the Shkodra gymnasium and boarders of “Maleve Tona” – with the names: Kolë Skana, Bardhok Prenga and Ndue Zef Ndoci.

Ali Taipi from the “Dudas” neighborhood, happened to be a prisoner who had sheltered a ballistics friend of his from the south, Major Bilbil Hajni. Aliu was a good and very beloved man and, despite his somewhat old age, I would always see him smiling and in good humor. His face was completely covered with fine lines, both deep and deep, and if he ever spoke about them, he would tell me how a child from his neighborhood, also an inmate, had one day spoken to Alicia through the crack of a door in the friars’ prison: “Ali, how come your face is so wrinkled like a slytepric”?! He would tell me this and laugh even harder than I did, and constantly brushing a gold tooth that shone in his mouth, he would repeat: “bitch of a bitch”!

Kolë Ndou, the flag bearer of Shala, was that quiet and gentle man, who, without being at all artificial, would seem quite imposing to stay in his place with the prestige of a man who, even in adversity, seeks to preserve and justify the importance of a mountain range. Kolë Ndou, with a pair of large moustaches that extended straight to the sides, would never move from his place, and two middle-aged men from Dukagjini, one of whom was tall and named Nikë, would constantly stand by him as a sign of great respect and would be available for everything, without letting him touch anything with his hand. Memorie.al

Continued in the next issue