From Dom Zef Simoni

Part Nine

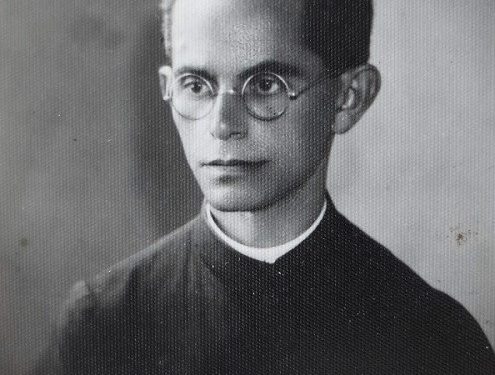

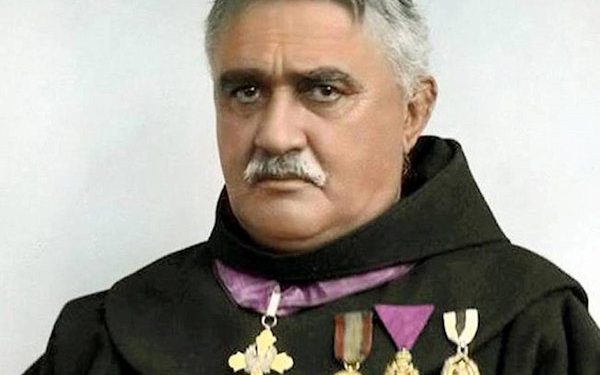

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990,” in which the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study begins with the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to detach the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply rejected Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

In addition to this grace, God also gave the first humans supernatural graces, which were contained in the gifts: not to suffer any pain, nor hunger, nor thirst, fatigue, sickness, or death. We had a dependence on God, to know Him, to love Him, and to obey Him. Then came the test. Not even God could make us independent, without putting us to the test, and this relationship of testing, being necessary, is life. A very ideal connection. A positive connection. The first two humans were warned about what evil is and its consequences, and the first two humans, out of pride to become like God, an external temptation from the devil, took the path of disobedience, which truly led them to eat the fruit. They lost God’s supernatural grace and the preternatural graces given to them freely by Him. Earthly paradise was lost. The doors of Paradise were closed.

Human nature was corrupted. Egoism, hatred, and revenge prevailed. Wars came. The world plunged into the sin of war. We inherited their sin, remaining the children of the first humans in wars and wickedness, leading to the corruption of the individual and consequently to evils and consequences in society. To leave a nation without spiritual reality begins its destruction. Can we humans achieve supernatural deeds without God’s grace? And can the efforts, the progress that humanity should make, be the smallest reform, the slightest guarantee, without fundamentally fighting the nature of sins and without having the spirit of the Decalogue [1] and the strength of religion? A great tragedy happened to us. We were darkened in conscience, in knowledge, in spiritual wisdom, in awareness. The downfall was general.

The events in the first part of the dictatorship – with executions, imprisonments, terror, the nationalization of persons, the furious destruction of the previous state, the overthrow of the system—are not unique; these events have happened everywhere in history, and our people endured them heroically, with a manly resistance that kept them on their feet. But the essence of the dictatorship lies in the construction of a new society, the formation of the so-called “new man,” which we would not cease to express with the words: “the corruption of character.” The dictatorship lies in its fruits, when people fall into wickedness and dissolution. The corruption of character arose from such social relations, where life meant work and prison, lay in the rigorous implementation of reforms, in the daily ties of human dependence, and in the people being led by wild, oppressive official groups and apparatus, by leaders full of base instincts.

The fearful majority, lacking personality, lived in servility and had many forms of espionage. It was a suffocating atmosphere of theft, trickery, propaganda, enmity, pressures, class warfare, and proletarian dictatorship, without the dignity of culture and the individual. With the closing of the churches, the ruin of corruption, disorientation, demoralization, and human evils, were openly visible and gaining strength. The events were linked to one another: the closing of churches, arrests of priests, terror trials, priests in forced labor.

At the Brick Factory

The three types of hard labor were: at the brick factory, in construction, and at the farm. I also had to enter. I was assigned to the brick factory, where people who had been in political and ordinary prisons were working. The word ‘work’ was synonymous with great fatigue, exhaustion, fear, insecurity, and low pay, which made them fume, talking to themselves about how they would spend the “historic fifteen-day pay,” in Albania. I somehow wanted to engage in physical labor, especially breaking up the earth, enjoying the planting, but the truth was that I lacked the strength. I was physically frail by nature, and I suffered from arteriosclerosis and two exostoses on my legs. I could not stand for long.

They chose an easy job for me: distributing the tiles with the speed of a young man, from the motor’s location where they came out, to the place where they dried. This work was a chain, non-stop for almost eight hours. To carry eight tiles per trip. All the movements of one workday were like covering thirty kilometers a day. This was every day. This was one day, two, and three. I got very tired. I couldn’t do it. Once, a soft tile fell from my hand to the ground. They quickly reported me. It’s called a denunciation. All work stopped. A meeting was provoked. It was a disaster.

“Be careful not to let the tiles fall to the ground,” said the foreman and the party secretary. “We are not calling this hostile work this time. But be very, very careful.” After three weeks, the supervisor removed me, seeing that I was incapable. “This is a workplace,” he told me. The strict supervisor, a former student of mine, without giving me any sign of recognition, issued a good report for me, sealed in an envelope, to be sent to the General Directorate of the enterprise, in which he had written: “No, he will not work, but he cannot. Send us strong people for work here!”

At the Agricultural Farm

I was sent to the farm, where I worked for several months. The work here was: planting, hoeing, harvesting vegetables, and fruits. They did not let me harvest peppers and eggplants for export. It was understood that such work would not be done by the “suspects.” They did not trust the reactionaries because, according to them, they would commit sabotage.

I was about to leave the farm as well, as I had a medico-legal report that absolutely forbade me from working in the sun and on my feet. A very serious event happened in our house. On the afternoon of July 25, my brother, Gjergji, came to my workplace, where I was working in the field. He was deeply grieved, deeply shaken. He informed me of the death of Keli, who had drowned in the water. A heavy trial for us as a family.

It fell to me to console my father, mother, sister, and brother. We all submitted to God’s will. I felt very sorry for him, especially for the nature he had, which I could call incorrigible. And whenever I had conversations with Father Meshkalla, he would tell me that he was a man lacking will. He was loving, kind-hearted, but dissolute, and all the people who heard of his sudden death felt pity. Gjergji and I had tried to help him with calmness and brotherly and human goodwill. I had occasions to give him reprimands, but loving ones. And he never took my words badly, saying: “You are right about what you tell me, but I make mistakes.” He would give me his word many times, but only kept it for a short time. There was no good outcome.

One day at mass, during the time of prayer for the living, having an elevated spiritual state and acting as an intercessor before God, I turned to Christ with these thoughts and memories: that I was ready to suffer any death for him, if only his soul could be saved.

And this mass and prayer took place three days before his death. Then and today, I considered his death providential. The place of death was Ishull Lezhë. After they had recovered his body, the next day, before noon, they brought the corpse in a coffin. My father mourned him like a patriarch, and my mother, dressed in black, was the woman of sorrows.

For a long time, I remained in memory of him. I had started to get physically tired. Around the month of December, I left the hard labor at the farm.

There was a complete lack of food. We lived on the labor of Gjergji, who worked in the Vau i Dejës hydroelectric power plant, in a three-shift job, amidst the cold and hunger, with his small salary and a pension that came to my parents, tried by that death. But none of us gave up. It was the strength of God in that pain, that trial, and the Christian courage that we gave each other. For us, nature and life were languishing, and I was entering, after a short while, into some secrets of the soul, into a world surrounded on all sides. Great clouds hung over my head and descended with heavenly weight into my soul. I sensed that these great forces had business with me, and they passed like flashes of lightning, one after the other. Clouds and gloomy thoughts.

My Pains

Dom Zef Simoni’s Reflections

On the Pains of the Soul

Sometime before I became a priest, and up until the day of my arrest, for nearly 16 years of my religious activity, which was very intense and involved contact with many people – and this good spiritual state would continue for another twenty-five years, as I write these lines – I declare the power of God in me, that for all these years, I would have no mortal sin of any kind in my soul. I had a continuous purity and peace. I have not looked at anyone with any ill intention. But suddenly, unexpectedly, like an arrow in the brain, a thought, a doubt, entered my mind.

The great God promised, for the good of my soul, that I would fall into certain tortures of the spirit, which are called scruples. My doubts were whether I had made my confessions well before becoming a priest. They started lightly and then became heavy. A crisis in the soul. The soul starts bleeding. A very serious sickness. A check of the past. Analysis. Confusion. I tormented the confessors. I told everything I intended to say and left nothing out due to shame, but I lacked precision. Seeing that I had fallen into scruples, they insisted that I had confessed well. If I confessed, after becoming a priest, any fantasy due to scrupulosity, I would still have to present it as material for confession from the past.

Now I would confess them, making exaggerations, distortions, and adding numbers, things that happened and things that did not. I would do this with many repetitions, details, specifics, precision, humility, and fresh repentance. I was not saying that I was lost, but it seemed to me that I was repeating Christ’s words: “O Father, why have you forsaken me?” I, too, as His priest, became like a strong, tormented, tested Christ. For me, Heaven was dark. I was exhausted from the tortures. I was almost completely broken. I would get soaked and dry. I would become drenched. I was drowning. Almost drowning. But I loved Christ intensely. Christ is a Being who must be loved. My most beloved figure and the figure of the world. A storm in space, in the sky, in myself. It seemed like I had two souls, two Zefs.

In one soul, the suffering, a life of scruples; in the other, endurance. The confessor would receive me with calmness, patience, and demeanor, “You must leave everything to me,” he would tell me. I did not even listen to the confessor. “Scrupulous people have a pride,” thus says moral theology and its great scrupulous authority, Saint Alphonsus Liguori. Scrupulous people feel that no one knows, no one understands like them, and they do not do this consciously, otherwise, a new sin would be added to the confession, the sin of sacrilege. The scrupulous person gets tired, has no more strength, and has no courage to say: “Let what may be, I will not lie!” I had entered torture. I was living in torture. I had entered as if into an internal madness. I began to melt away, I became like a corpse.

Externally, I behaved well with all people, out of fear of sin. Very well, even. I had logic. I guarded myself intensely, not to speak any word, no matter how small, to anyone, not to express any anger toward anyone, because I thought I might be committing a sin. A very grave sin. A sin deserving of Hell. For me, venial sin, the small sin, no longer existed. No difference from mortal sin. Therefore, I stood like a statue before others, like a being without personality, because even when I felt I should defend myself, I did not. I had fallen into this state. However, defending the rights of others was something I did not lack. I had inner abnormalities, yet was completely normal before others. I lived like a wretch and fought like a hero. I had no certainty about myself. Moments of certainty and joy I had strongly within the confession.

And after a few hours, the fever of scruples would begin again, and it seemed to me that I was back in the zone of being lost. I was a very sorrowful being. In a state that would continue intensely for nearly three years, because afterwards, they started receding due to the help of the priest and the improvement of my health. And when I began to emerge and see that I had climbed upward. A new awareness also came to me, making me patient, broad-minded with others, helping those who suffer, those with spiritual delicacy, and those who weep and sigh. I put aside my self-interests, egoism, and every petty cleverness, because the Sacrament of Confession, which I had deeply entered, was also removing my disorders. Confession without scruples completely links you to God.

I have learned that no one is a better person than in those moments when they confess. Even Christ, who founded this sacrament, took into account our psychological need, that whoever we are; we must show it to someone. Then God gives us the grace to understand who we are. Through confession, we are revealed, elevated, transformed, we transform potentials into acts, and we move towards the good state of the act, true likenesses of God. To go and confess once is to fulfill, for a few moments, the science of supernatural knowledge, because confession cleanses and invalidates. For health reasons, the neurologist also advised me to spend the summer time among the mountains. His suggestion was Razma, and to combine this with the climate of Shirokë, a small village by the Lake of Shkodra.

I would go to Razëm for seven years, seven summers. A place of mesmerizing beauty, amidst beeches and higher up, pines. I would take beautiful walks to the “Cave of the Sheep and the Pigeons,” among silver springs and the “Well of Granashdol,” at the foot of Veleçik, from where I could see much of the horizon: the lake, the Alps, the plain of Tuz, and breathe the rosy air and the aromas of mountain flowers and soft meadows. I had my good father with me, and every week my brother, Gjergji, would come to spend two or three days as well. I truly began to be renewed. Weakness was leaving, the scruples were leaving, and full of joy, these were replaced by meditations. I was reading “The Highland Lute” (Lahuta e Malcisë).

I read it at the foot of Veleçik, together with Dom Kolec Toni, who had come a little later to Razëm and had also rented a room to spend the summer season. Where could be more beautiful than those mountains to read ‘The Highland Lute’ than in the place of the events, on the field of the Zanas (Mountain Fairies), amidst the mountains of the highlanders?! I had rented the house of a highlander named Gjeto Prelë Kota. When he was in a good state of wealth with flocks of sheep, Gjeto lived in a hut, which he had now put up for rent for those who came to summer there. And for himself, he had built a new house when his wealth had almost completely run out, and he was living on wages. Of the two rooms in this house, he decided to rent the larger one to the blessed family of Gac Zojzi, a teacher and painter, and the other to me.

This family stayed for the entire month of July, and during this time, I secretly gave the Catechism to their eight-year-old daughter, and gave her first communion there, and Confirmation in Shkodra, at the house of her grandfather, Zef Doda, the school principal with whom I had worked and to whom I had given the news of my departure from teaching. The day of the girl’s first communion was a celebration for both families; it was an unforgettable Sunday in captivity. In the following years, my father, my brother, and I took a ground-floor room in their hut. We had nearby the honorable, brave, and honest family of Ndok Kiri, the nephew of Father Frano Kiri.

Mass in Razëm

In my room, I celebrated Mass every day, and Ndok’s family would come to it every time, including his wife and two small children: Franci, over five years old, and Nesti, nearly four. I recall this event: one day when I went down to buy something at the shop, in the center of Razma, and went up to return to the room to celebrate the Holy Mass, Nesti came out in front of me saying: “Uncle Zef, say the Mass, and I will stay outside to guard you, so that no one comes.” Gjeto Prelë Kota was a sharp, energetic man of his word. If he had been educated, he would have been an orator, perhaps like a Father Anton, like a Dom Lazër Shantoja, and so many others.

His wife was the magnificent Mara, a daughter of Kastrat. She was like a matron, with physical beauty and personality. They had three married, good sons and five noble daughters, married in different places. One time Gjeto was leaving the house, to go down to the center of Razma. He was riding a donkey, well-dressed, with a jacket over his back. I said these words to Gjeto: “When the time comes for you and Mara to die, these mountains will become poor.” He was very pleased that I gave him this honor, and the pride of the mountains was revealed in him. I swear to you that, if Gjeto took off the white qelesh on his head and Mara the xhubleta on her body, and they dressed in Western style, they would be another couple, in terms of beauty, and being good people, when their time came to die, they could go to Paradise; they could live entirely well even in Paradise here on earth.

To go to Paradise, you must not have sins; to go to Paradise; you must know the language and have etiquette. And my mind went to the preface of Fishta, which he wrote for Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi’s ‘Code of Lekë’ (Kanunin e Lekës). There, he speaks of five civilizations. He puts the main civilization, the Christian one, in our mountains, in the third rank. Once Mara asked me what time it was, as she didn’t know, because the clock had been broken for a long time. “Has noon approached, because we are used to eating our midday meal with the toll of the bell,” which rang at 12:00 noon. In this instance, she glanced from the house towards the church, which had been turned into a warehouse, and wept. “It is almost 12:00. It needs another quarter of an hour,” I told her. They were regular, knew and kept the Ten Commandments of God, and knew some points of the catechism, which they had heard in the sermons when they attended Mass.

The Highlands and Christian Civilization

Every Sunday, those residents with natural sharpness would receive the word of God from the priest and the intellectual, as in the capitals of Europe and the world. In those mountains lived a people with genius qualities, a race with the features of thinkers, artists, and mathematicians. Father Gjergj Fishta, Father Ambroz Marlaskaj, Father Benardin Palaj, Martin Camaj, and many others have emerged from the mountain regions, and (the nation) has lost contingents that could have emerged and enlightened our nation and our culture. These areas, where one does not see a proper road, or a proper dwelling house, with people stripped bare and unfed, were left in oblivion and behind, deliberately, and without any care for them, by every government, leaving them to live at the mercy of fate, and that in certain historical circumstances, moments might come when they explode badly, without even knowing what they are doing. Christian civilization is primarily a civilization of the heart. “If we don’t have this heart, we don’t have it anywhere,” states a modern French writer. Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)