By Dom Zef Simoni

Second part

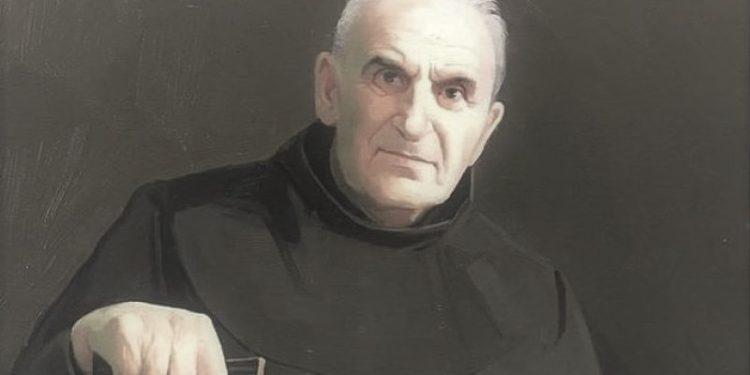

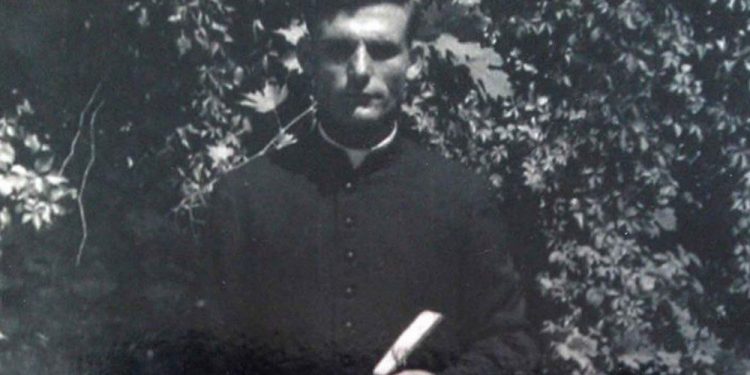

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, entitled “Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990”, where a Catholic cleric from the city of Shkodra who suffered for years in the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and on April 25, 1993 he was ordained a Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, he stopped long at the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church in the regime communist, from 1944 to 1990. The complete study of Dom Zef Simon, starting from the attempts of the communist government of Tirana immediately after the end of the War to separate the Catholic Church from the Vatican, initially forbidding the Apostolic Delegate to return to Albania, Imzot Leone GB Nigris, after his visit to the Pope at the Vatican in 1945 and then with the pressure and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi and Vincens Prenushti, who strongly opposed the “offer” of Enver Hoxha and as a result were fired by as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured and sentenced to prison, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

Followed by the last number

Study of Dom Zef Simon

Mons. Frano Gjini experienced the torture of hunger and the great cold, hanging them out through the trees of the Security yard, in addition to countless heavy blows and dropping him in the 10-15 cm sewage. of WC. Dom Simon Jubani started the long prison, when his brother Dom Lazër Jubani was coming out. They did not see each other with their eyes. Dom Lazri was forced to go to work in Shkodra and at work he was poisoned with tomatoes. He was kept in the hospital for a day, but was released without treatment. Dom Simoni would spend many years in prison, where he would be sentenced to another ten years in Burrell Prison. A total of 26 years.

Dom Nikolle Mazrreku and Father Zef Pllumi would be arrested and convicted after a public trial at the Stigmatine Sisters Church. This would be their second time in prison. Dom Nikolla would serve a total of 25 years in prison and 12 years in exile. Father Zef Pllumi, 25 years.

Dom Mikel Gjergji (Beltoja) after the strong tortures we did in Sigurim, and in the courtroom, for the strong words he said, where he was tortured by the police, his body was covered in blood with biza, and in was finally shot in January 1975.

After the shooting of Father Giovanni Fausti and Father Daniel Dajani, the house of the Jesuits was closed and a total of 200 foreign Italian missionaries, 25 of whom were priests, left for Italy. Prior to the departure, a search of the Jesuits’ house was attended by an army of 800 men. In 1946, all private schools in Albania were closed, with those of the clergy and sisters, who had maintained a spiritual, social and intellectual life with a high national level and equivalent to those of Western Europe.

The printing presses of the clergy, such as that of the Jesuits and the Franciscans, passed violently into the hands of the state and the publication of any book or magazine was not allowed, such as: “The Messenger of the Heart of Christ”, “The Bell of the Sun”, “Zani i Shna Ndout “,” Hylli i Dritës “,” Leka “. People who had these periodicals in their homes near private libraries were often forced to hide or burn them for fear of sudden and furious security checks. The museums of the Jesuits and the Fretans were also taken over with collections of ethnographic, archaeological, and numismatic materials, with all their rich libraries, such as that of the Jesuits with some 40,000 volumes.

Religious societies, never for political purposes, as the rabid regime slanderously accused, but founded to educate the youth religiously and intellectually and to keep close to it and the people with good moral and moral habits, all closed down. Thus the “Catholic Action” near the Cathedral, with Dom Mikel Koliqi as leader, in the villages and highlands with their parishioners, the “Dom Bosko District” near the Jesuit Eten with Father Jak Gardin and in Tirana the “St. Prosprit Circle”, which led him Pjetër Meshkalla, “Antoniane Society”, near the Franciscan Eten in the city, villages and highlands where the Franciscan parishioners served, had for different leaders Father Lekë Luli, who was assassinated by the communists on the Shkodër-Kukës road in 1944, Father Agustin Ashikun, Father Gjon Shllaku, Father Mëhill Miraj; “The Society of the Daughters of Our Lady”, near the Stigmatine sisters in Shkodra, and many other places where the sisters were in Shkodra with Ethnic Franciscan leaders, such as: Father Vinçenc Prennushi, Father Marian Prela, Father Frano Kirin, Father Donat Kurti.

The Third Order of St. Francis, for men and women, with the founder and leader Father Marjan Prela, the association for men and women of Our Lady of the Rosary and the Congregation of Our Lady of Lourdes, for men and women, near the Jesuit Ethen, led by Father Zef Saraçi, the “Kryqzaten” children’s association, near the Etienne Jesuits, led by Father Jak Gardin, Dom Ernest Çoba, and their assistant, the Jesuit Fra kesk Ljarjen; The uratorium that had gathered the working youth near the Jesuit Athenians and the Orphanage of the Heart of Christ near the Jesuit Athenians.

All were scattered throughout the city and misery fell everywhere. A spiritual exhaustion tormented the hearts of all the people and the youth in the persecution of the early years. Young men and women, brave for “Fé e Atdhé” were arrested and imprisoned.

No activity was allowed from these societies, neither social, nor film screenings, nor theatrical, nor sports activities, although among these societies there were sports, theater, excellent church and classical music and many other activities.

Now began a loss, a regress, and a century-old destruction.

The institutes of all the sisters, such as: Stigmatine, Servite, Saleziane and Vicenciane, wherever they were in Albania, except the Servite sisters of Vlora, were closed and the sisters were forced to go to their families, without being able to go out in their regular clothes… Many of them were put to work, especially in hospitals, and the sacred services of the sick were done with love, leaving a good example to be respected by all, by the whole public. The churches were unbroken and full of believers, perhaps even more than before, but in Shkodra and among the dioceses the Archbishops, bishops and priests were missing.

The Archbishop of Shkodra, Monsignor Gaspër Thaçi, died after a serious illness and after a strict observation, on May 26, 1946. A funeral was held in the city and when the procession was returning near the Cathedral, an incident occurred. A truck had hit the road in the middle, we put them on purpose. Then young men and strong men avoid the truck to make room for the funeral.

At the state high school, the directorate barred students from attending the funeral, but it was impossible to stop. The young Catholics climbed with great pain towards the Cathedral. For the last time, two choirs sang together: The Cathedral and the Franciscans, the funeral Mass and “Libera me Domine” by Lorenzo Perosi, organized by Father Filip Mazreku, and conducted by Prenkë Jakovën.

The Mass was celebrated by the Deputy Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Frano Gjini, and the occasional sermon was delivered by the orator, Monsignor Gjergj Volaj, a sermon that would expedite the arrest of the orator.

I was soon honored, the parish lacked priests. “People saw the mass and went in and out in silence. It was fear. It was scary the situation, the road, the sight, the dusk, the night hours, the awakening: black darkness.”

The palace of the archbishopric was taken over by the state, to become the residence of the families of the officers. Only a few rooms downstairs were left to the Church. Only Dom Ernest Çoba served in the Cathedral Church, Father Florian Berisha and his Jesuit brother esesk Ljarja, while in the Franciscan Church of Gjuhadol and Our Lady of the Rosary, Father Marjan Prela and Father Ferdinand Pali, suffered these hardships, the first some years in prison and both also internment. Near the Franciscan Church were the fraternities: fra Ndou, fra Salvatori and fra Nicholas, like light shadows, experienced near those churches and blessed letters.

In the church of the Athenian Jesuits, entitled that of St. Joseph, was Father Zef Saraçi and Jesus’ brother, Karlo Markovic. The city of Shkodra, which had close to fifty priests, a great privilege, remains after the “strong earthquake” with these priests: Father Justin Rrota paralyzed in bed, Father Marin Sirdani, who tried prison.

Father Zef Saraçi, blind in two eyes and Father Pjetër Tuci, ill on his feet. This is a salvation with crimes. This is the first stage. Other salvages came later that would last nearly fifty years, a real blood look and being of every deadly moment.

* * *

The second phase was the reduction of toughness against the Church clergy, without ever giving up the fight against religion: it is a phase of great deception, beginning in the 1950s, after the severance of relations with Tito’s Yugoslavia until the 1960s, when relations with the Soviet Union broke down.

The state sought to regulate relations with all religious institutions, mainly the Catholic Church, through a statute. For this, some contacts were started by the government, through its representative Tuk Jakova, of the Franciscan Father Marin Sirdani. At the meeting of the clergy chaired by Monsignor

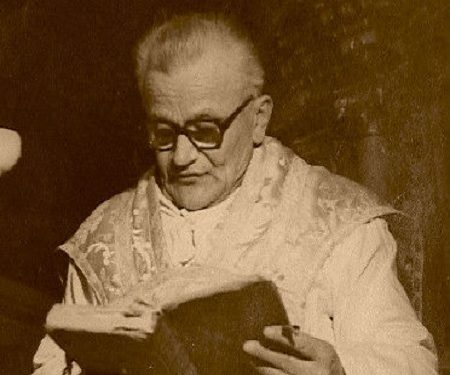

Bernardin Shllaku, the elder bishop, the only one who had survived, presented the regular Statute under the Ecclesiastical Code, but the communist government did not accept it.

In a second meeting of the clergy that took place in a few days in the Archbishop’s Palace of Shkodra, a Statute was drafted and presented with some differences from the first. But the government became furious and, as furious as it was, did not accept it at all. The state then introduced a statute of its own. But the clergy could not accept Monsignor Bernardin Shllaku, in the meeting he had at the Prime Minister with Mehmet Shehu, he said: “We cannot accept this Statute.” In a conversation between the Prime Minister and the Monsignor, Mehmeti asked to know where the great difficulty was.

The Monsignor’s reply was: “Let me be handcuffed from now on, if I am not at least guaranteed the appointment of bishops by the Holy See.” Mehmeti agreed, they said that the appointments will be made by the Holy See, but the materials were sent through the Government, without being written in the Statute. So, the Statute presented itself as such, but in reality, there was no schism.

The clergy meeting accepted the latest version in the trust of Bishop Bernardin Shllaku. Father Zef Saraçi, a distinguished professor of theology and code, said these words: “We are entering under the umbrella of the Monsignor”. Mehmeti told the Monsignor to submit to the Prime Minister a proposal for the appointment of four new bishops. But the Holy See did not name any of them, she chose two others who were Monsignor Ernest M. Çoba, for the Archbishopric of Shkodra and Monsignor Pjetër Dema, for the Archbishopric of Durrës.

Later, during the dictatorship, they were appointed by the Holy See, on the proposal of Monsignor Çoba, and two other bishops, Monsignor Antonin Fishta, ordained in 1957 as Bishop of the diocese of Pulti, in the place of Monsignor Bernardin Shllaku, died in Nanduer of 1956 and Monsignor Nikolle Troshani, ordained in April 1959, as bishop of the dioceses of Lezha and Durres, in place of Monsignor Pjetër Dema who died. But the diocese of Durrës was kept hidden from Monsignor Nikolla, under pressure from the government.

Other connections with the Holy See, apart from the appointment of bishops, have been very few. Only three of which were also carried out strictly through the Prime Ministry. Those connections were: sending the telegram of condolences for the deacon of Pope Pius XII and that of the congratulation for the appointment of Pope John XXIII and later receiving some breviares.

After the death of Monsignor Bernardin Shllaku, according to the Statute, he was named President of the Catholic Church in Albania, Monsignor Ernest Çoba was named.

The state had set up a special office with a clerk of its own to deal with representatives of the clergy of all faiths.

Monsignor Ernest Çoba would start secret religious relations with the Holy See through the Italian Legation in Tirana, through his sister. The problems were religious. From time to time, her sister went to the Legation to receive the pension of her Italian husband, living in Italy. To write on some cigarette papers, the materials of the Monsignor, were given to the clerk by the sister. This work continued for several years. This would be the main reason for the arrest and sentencing of Monsignor Çoba.

During this phase a number of clerics were released from prison, who were appointed to various parishes, always with the approval of the state. With the approval of the state were approved some who would take up the priesthood such as: Dom Ernest Troshani, Dom Tish Lisna, Dom Simon Jubani, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Ndoc Volaj, Dom Martin Trushi, Dom Injac Dema, Dom Mikel Beltoja and Dom Marin Shkurti.

Total nanda itself. Six others were ordained secretly, without the permission of the government by Ernest Çoba, and are: Father Gjergj Vata and Dom Ndoc Noga, on March 19, 1954, Father Zef Pllumi, ordained on May 1, 1956; Dom Kolec Toni and Dom Zef Simoni on February 9, 1961 and Dom Luigj Kçira on March 24, 1963.

There was no press during the dictatorship. Only the religious calendar was published in Tirana, in the state printing house “Mihal Duri”. The seminar was allowed by the Statute, but in reality, did not exist at all. His being would be dangerous, why State Security would stick their noses in there. When some priest-professors were released from prison, such as: Father Pjetër Meshkalla, Father Mark Harapi and some others, some students would secretly study at the Palace of the Archdiocese.

The church was under trial and in handcuffs. The state, by statute, gave an aid to the Church, a subsidy. The archbishopric almost did not even have a table and chairs, because they were all seized by the State. After the liberation of the Archdiocese Palace, inhabited by the families of officers, various offices were formed, with officials being paid from the subsidy. At first all the priests received a small subsidy, but later it was removed, almost completely, because the subsidy from year to year was reduced.

At this stage, always with fear, a certain religious vitality was seen, on the occasion when the new altar was built, the decoration of the Church with murals and the consecration of the Cathedral church on April 19, 1958, a Sunday, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the start of works. But it did not take long and in my nanduer of this year a terrible trial started in the cinema hall “Republika”, against the good and innocent priest Dom Ejell Kovac, we are seriously accused.

Dom Ejell Kovaçi was shot. In April 1959, the parish priest of the Buna Coast, the arsonist Dom Dedë Malaj and Father Konrad Gjolaj, were shot and sentenced to 25 years in prison. “Noise and commotion in Albania. The class war was at its zenith.”

At the Prime Minister’s Office, officials dealing with religious communities held military ranks. They were prudent people who spoke lightly and a little loudly and gave clear answers to the needs of the church.

On the occasion of holidays, such as: May 1 and November 28-29, the state called on religious communities to be found in the rostrum of Tirana. Officials also came to congratulate him on Easter. Later they started to reduce the arrival. They sent short telegrams: “For many years Easter”! Later, only: “Congratulations!”

When personalities from Albania’s friendly countries came, especially from the Soviet Union, sister democracies and popular China, religious communities were also invited to banquets at the Palace of Brigades.

A memory: in 1959 Nikita Khrushchev came to Albania. Representatives of the religious communities were also invited to the Palace of Brigades that evening, and they were placed at a table in a slightly hidden corner. Before the end of the evening, Khrushchev turned his eyes to the religious representatives and at his request, together with Enver and other officials, addressed them to greet them.

An Albanian official, proudly, informed the high official that we have good relations with the communities and moreover announced that we also have a Statute. Khrushchev was very surprised and with a special expression on his face, he said: “Statute”! He made it clear that he did not like it.About 1960, Albania broke off relations with the Great Soviet Union and began relations with Mao Zedong’s China.

At first it seemed like a quiet period, but it was a situation of subtle subtlety. From time to time, especially in the villages, the presidents of the councils imposed on the priests with heavy orders the schedules of the mass. Masses should not be celebrated during working hours, which lasted from 6 o’clock in the morning until late hours of the day. With great difficulty the children were prepared with catechism for the first Communion and Cremation among the mountains and villages. This was complained of by the parish priests near the bishop and the bishops of our dioceses.

A generally bad wind was blowing, a savagery was increasing day by day, a new attitude towards the Church was being introduced, a new war with other dangerous content against religion. The State Party, through its youth, women, and pioneer organizations, under the auspices of the Security Forces, began to closely monitor the attendance of the Church.

This had started a little in 1959, when especially teachers were forbidden to go to church, and after 1964 this ban gradually began with the clerks and young people and school children. Strictly atheistic work was done especially in schools. Teachers, especially those who were party members through various lands, unmasked the clergy and the reactionary role of religion. The slogans “Religion is opium for the people” were displayed in the school corridors. /Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue