By Dr. Dom Nikë Ukgjini

-Brief historical overview of the tribe of Kelmendi-

Geographical scope

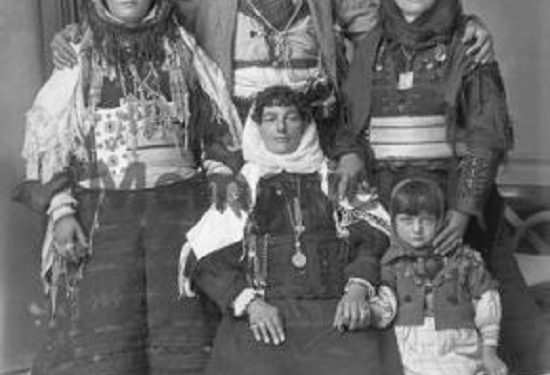

Memorie.al / The Kelmendi Highlands lies at the northern edge of the Albanian Alps, in the triangle formed between the state borders of the Republic of Albania, the Republic of Kosovo and Montenegro. In the ethnographic sense, the tribe of Kelmendi belongs to the mountains of the Great Highlands. According to the tribal alignment, Kelmendi is bordered by Hoti, Kastrati and Shala in the South, with Gash and Krasniqe in the East, and with the Vasojevics, Kuči, Triepši and Gruda in the North. The inhabitants of this tribe live mainly around the two sources of the Cem River, Vukli and Selca, and the Vermoshi River. The municipality of Kelmendi today has 6344 inhabitants, concentrated in the villages: Vermosh, Lëpushë, Selce, Tamarë, Brojë, Kozhnja, Nikç, and Vukël.

The name of the tribe

The name of this tribe comes from the Latin word clemens-(tis), i.e. wise, simple, good. This designation of the nature of man, we later find as a personal name, Clemens. Among the writings of foreign researchers, we find in different phonetic forms “Klemnti”, “Klimenti”, “Clementiner”, etc., while in the Albanian language “Klmen-Klmente”, namely “Kelmendi”. For the first time, in today’s sense, as a personal name, we find it in the third deputy of St. Peter, Pope Clement I (90-101), who while preaching the word of Christ among the pagans, was martyred. The Kelmendas have kept this for the Saints and protectors of the tribe throughout their history, dedicating the prayer temples among the churches to him at the same time. For this reason, the Kelmendas especially honored the Popes of Rome. This is proven to us in a report about the Kelmendas sent to the Holy See in 1636, by Father Bonaventura. He writes that when the Serbs of the Orthodox religion, who came to the lands of Kelmenda to escape from the barbarism of the Turkish army, began to insult the Pope, the latter threatened to expel them from their tribal territory.

Origin

As a toponym, this name is identified with the name of the Byzantine fortress “Clementiana”, which is mentioned by the historian of the era of Justiniana Prima (527-565), Procopius of Caesarea. According to the Serbian historian, Vladislav Popovic, this castle should have been located between the Kelmendi villages, or north of Shkodra Lake. As for Sufflay, this fortress should be on the Roman road Shkodër – Prizren, at the customs house of Holy Salvation (Svetog Spasa). The origin of the tribe of Kelmendi, as well as other tribes of the Great Highlands, according to scientific treatments, is still unclear to this day. But all this does not mean that efforts should not be made to supplement or elaborate even a little bit what Albanian and foreign albanologists, such as: Selami Pulaha, Rrok Zojzi, Milan Šyfflay, Franz Baron Nopcsa, Georg Stadtmuller, Giuseppe Valentini and recently, Peter Bartl, have written about the origin of the tribe in question, as well as about other tribes of the Great Highlands.

Foreign albanologists as well as Albanian ones, in the absence of written documents, explain the origin of this tribe according to the concepts of folk tales. Thus, according to the Franciscan missionary Bernardo from Verona, who for many years worked among this tribe, in the report sent to the “Congregation for Evangelization” in 1663, among other things he writes: “it is not easy to say from this tribe originated, but it has become a habit to say that this population is a descendant of the Kuças or other neighbors”; , while the Archbishop of Shkodra (1656-1677) and later of Skopje (1677-1689), Pjetër Bogdani, in his report of 1685, sent to the Holy See, among other things, says: “according to the narrator, the first of the Kelmendas came from the upper course of the Moraça River”, i.e., from the old Albanian hill tribes, which, according to Valentin, are: Piperri, Kuçi, Vasojeviçi, Bratonoshiqi, Palabardhet-(Bjelopavliqi) etc.

Then, the first of the Kelmendas married a girl from the Kuçi tribe and named the first born son Kelmend. While the prominent albanologist Zef (Giuseppe) Valentini, after many versions, as the most reliable variant, maintains that this tribe derives from the old Kodrinor Albanian tribe of Kuçi, and the latter derives from the Berishë tribe, which in the documents of we find since 1242. However, we find a documented surname of this tribe in 1353 under the name, Gjergji, son of Gjergj Kelmendi from (the place) Spas, (dominus Georgius fulius Georgii Clementi de Spasso) at the aforementioned fortress Clementiana, as a well-organized tribe, we meet in 1497.

However, when we say that the origin of tribes according to the scientific and popular concept is usually connected with the name of the toponym, or with the name of an anthroponym in the patronymic (surname of a person), later in the name of the brotherhood and finally in the name of the tribe, and that, the waste of the tribal order in Albania are inherited from the most ancient times of our history, that is, from the Illyrian trunk, and when on the other hand we learn how ancient the origin of this name is, we naturally ask ourselves the question: Maybe the words of the German encyclopedia, published in Altenburg in 1824, which dedicated 22 lines to this tribe, and where it says, among other things: “The Kelmendas, the Arnauts, are from the old Illyrian tribes” can tell us something. So, maybe we are dealing with an ancient tribe, which during the Slavic-Avar barbarian invasions in our lands, remained completely underground until the 11th century (like the very name of the Albanian people and the history of the Albanian church), because, as we know, this tribe in the course of the Albanian national history, played an important role in preserving the national and religious identity in Northern Albania, which we will briefly get to know in the following.

On the history of the tribe

As can be seen in the detailed records of the Book of the Sanjak of Shkodra from 1497, before the Turkish invasion, the Kelmendas lived in two villages: the village of Selçisha, where the village of Liçeni was located, and the village of Çpaja-Spai-Ishpaja, where four villages were located and there were 152 houses. . The common land was called Petersjan-Petershban-Bishtan, and it is located one hour away from Selca, north of Podgorica. The fact that in 1582 only 70 houses were recorded in Kelmend clearly shows that with the arrival of the Asian conqueror, this tribe was forced to move within the Highlands and move to the villages of Anamal, the villages of Muriq, Shestan and Goljemadhe in Montenegro1. However, according to the report of the providur Marin Bolica, the process of territorial organization of this tribe as well as the tribes of Hot, Piper, Kuç, etc., at the end of the 16th century, was completed and the basic territory of Kelmendi was already formed.

In his 1638 report sent to the Holy See, the Bishop of Sapes, Frang Bardhi, says: “The Kelmendas live among very large mountains and with strong positions between Bosnia and Albania. They are of Albanian nationality, speak Albanian and are included between the borders of Albania; exercise our holy Roman Catholic faith”. Otherwise, according to the documents, since 1671, we find this tribe divided into three brothers: Selcë, Vukel, Nikç, and in 1688, the fourth brother Bogë, which in fact represented the four branches of the tribe spread across four valleys. According to the bishop of Sapa, Gjergj Bardhi, who on July 8, 1634 made a pastoral visit to the mountains of Dukagjin, Pulti and Kelmendi, in this year, this tribe had 300 houses with 3200 souls22).

The Kelmendas during the Ottoman occupation

After the fall of Medun in 1457, and finally, of Shkodra in 1479, the invading Ottoman army slowly managed to extend its power to the Malësia (Greater) regions. The Kelmendas for the most part, despite the recognition of the sultan’s power in 1497, despite the great life difficulties they faced, remained unsub jugated by not paying any kind of obligation to the conqueror until 1664. The evidence for this is the fact that the Kelmendas were not registered in the Book of Sanjak of Shkodra, from 1485.

There was almost a tradition in all the highlanders, to refuse the hand of the Turkish conqueror. This can also be observed in the relation of Marin Bic (1608-1624), the archbishop of Tivar, who in 1610, wrote to the Holy See, that the highlanders are only of the Latin (Catholic) faith, divided into tribes Kelmend, Grudë, Hot, Grise, Kastrat, Tuz, Shkrel, etc. As for the Kuchi, half of them belong to the Orthodox religion, the rest to the Catholic religion, and all these tribes live in unsuitable mountains and have never submitted to the Turks. Otherwise, Bici, in this connection, mentions the name Kelmendi for the entire northern Albanian conglomerate, including the semi-Slavized tribes such as the Bjelopavliq (Palabardhet), the Piper, the Bratonozhiq and the Kuqasi.

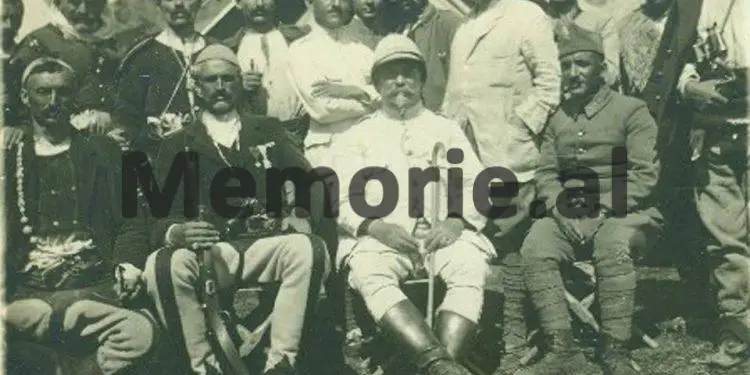

The first organization of mountaineers of Balkan proportions, to oppose the Turks with the support of the allies, the Holy See and the Spanish, held in Kuc in 1614, made Kelmendi unite 650 warriors and form the military alliance “Union of the Mountains” “, for the liberation war against the Ottomans. Thus, the highlanders became an important power, which determined the fate of the Sanjak rulers in their power struggles. Not many years passed and most of the mountainous areas, leading continuous uprisings, rejected both the obligations of 1497 and the timar regime. Thus, at the beginning of the 17th century, the Spahis were permanently expelled from 11 provinces of the Great Highlands, i.e. also from Kelmendi, which, according to church relators, made the biggest uprisings, being also favored by the geo-strategic location. Most of the highlanders, after great sacrifices, destruction, damage, taking people as slaves, remained free peasants.

The Kelmendas, free from the enemy in their mountains, due to the lack of land, fought with the other enemy, poverty, which forced them to rob the feudal estates, trade caravans and sometimes the cities themselves. M. Bolica, in his chronicle of 1614, says that the region of Plava and Gucia, which was administered by the Turks, was destroyed many times by the plundering of the Kelmendas, who lived in the immediate vicinity. For this, the High Gate, in 1612, was forced under the leadership of the pasha of Podgorica, Cem Çaushi 31) to build a large fortress above the village of Gerçar, in the place called Godilje, the fortress that was named the New City. Otherwise, the people of Kelmenda call them hardworking and brave people. The bishop of Sapa, Frang Bardhi, about the attacking Kelmendas, in a report from 1638, says that they made continuous attacks on caravans in Albania, Bosnia and Serbia.

- Bolica also writes that the attacks of this tribe, as well as other tribes, have reached Filibe, today’s city of Plovdiv in Bulgaria. The people of Kelmenda probably did this because of the collection of war material, to fight against the Turks. This is seen in the liberation wars led later against Asllan Pasha of Podgorica, in 1613, Ibrahim Aga of Shkodra, in 1617, and Mehmet Bey in 1633, etc. In 1638, after a long preparation, with the directives of Sultan Murat IV (1623-1640), under the leadership of Vuço Pasha from Bosnia and the Sanjakbey of Shkodra, Ali Çengiq, where 15,000 soldiers participated, according to the bishop of Sapa Frang Bardhi (mainly composed of Turks, Dalmatians, Bulgarian Serbs and Bosniaks), the Turkish government waged a massive, decisive war for the destruction of this heroic tribe. But even after a one-year war, he did not manage to defeat the brave Kelmendas, who with a selfless fight managed to repel the enemy in 1639. They even said that the Pope of Rome himself has prayed for us so that God will help us in this battle. Thus the people of Kelmenda, although crushed, preserved the legacy of the ancestors: “religion and homeland”.

However, the Kelmendas did not have to wait long for their war: in 1645, the 25-year war for Crete began a Venetian-Turkish confrontation that had the arena of war in the Balkans. During this time, the Kelmendas entered into an agreement with the Venetians and in August 1648, they received an invitation from the parish of Kotor to oppose the Turks together to liberate the Albanian lands, up to Krujë. February 27, 1649 was set as the date to attack Shkodra, but even after the great preparations that were made in Budva, the attack did not take place.

Later, due to the preservation of their positions which were always threatened by the Ottoman hordes and due to the Islamization of a part of the tribe, the Kelmendas for a while withdrew from this Venetian agreement, in their own lands. But, during the years 1686-1699, when the Austrians advanced to Prizren and Skopje in the war against the Ottomans, the Kelmendis again changed their position and joined the Austrian general Piccolomini, who had included the tribe of Kelmendi in the agreement of October 12, 1689. The doubt expressed by the Serbian authors, on the participation of the Kelmendas in the great Austrian-Turkish war (1683-1699), is unfounded. Austrian sources at the end of the 17th century clearly prove this.

Not by chance, Count Luigi Ferdinand Marsigli (1658-1730), in a memorandum addressed to King Leopold I, on April 1, 1690, about Albania and the Kelmendas states that; “Picolomini made an agreement with the Kelmendas and those who lived in Rozhaje and around it” and, that; “The Kelmedas live in Turkish Albania”. “They – continues Marsigli – stretch from the vicinity of Pristina, in Peja and Plavë to Shkodër”. He probably says this because the Kelmendas were also scattered in these places, at least in the district of Peja. The Venetian map of Giovanni Giacomo Rossi, from 1689, tells us about a similar extension, where it is clearly seen that the territory of this tribe extends to Herzegovina. Count Marsigli writes this to show the great importance that this tribe had. Marsigli, who enjoyed great authority in the headquarters of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, could not have been misinformed, as Rajko Vaselinović also affirms.

In 1700, in order to defeat the Kelmendas, Porta e Larte engaged the pasha of Peja and Dukagjin, Hodoverd Mahmutbeg, who, with trickery and money, penetrated towards Ulcinj and Tivar, after subduing Malesia e Madhe. According to the report of 1702, sent to the Holy See by the archbishop of Skopje, Pjetër Karagaqi, the Kelmendas, after a prominent resistance, by great violence, 274 families were forced to move and settle in the district of Novi Pazar, in Peshtër, Rozhaje and Rugova. Thus, the irreversible, now massive migration of the Kelmendas continued, which had started before, in the years 1661, 1667, 1669, in small groups to Plavë e Guci. The Archbishop of Tivar, Vinçenc Zmajeviqi (1701-1712), best announced their poor economic and religious situation in his pastoral letters sent to the Holy See, from 1702 onwards who had already taken them under his paternal care.

During the Russo-Austrian war against the Turks (1735-1739), the Austrians again tried, as many times before, to free the Balkans from the Turkish hordes and even reached the interior of Serbia, where on July 28, 1737, without a fight, they took Nis and Novi Pazari. Serbian Patriarch of Peja Arsenije, IV. Shakabenda, the archbishop of Skopje, Mihill Suma, and Ohrit Joasaf, entered into secret talks with Vienna, to organize an uprising. The Kelmedas, together with the other tribes of the Highlands, on this occasion gave strong support to this organization. On the other hand, the imperial headquarters had promised the Albanians that in the event of peace and if their regions were not freed from Turkish rule, the highlanders would be able to emigrate to the imperial regions, i.e., to the interior of Serbia.

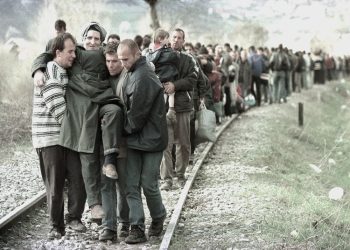

But, unfortunately, the destruction happened faster than the Kelmendas and other insurgents had imagined. Thus, the Austrians were forced to retreat and give up Pristina as well. On August 24, Novi Pazar fell, where 200 Kelmendas had advanced, 200 from Hoti and 100 from Gruda. The Albanian and Serbian insurgents, together with the Austrian troops under the command of Colonel Lentulus, had to retreat to Kryshevc. After this failure, on October 4, the Kelmendas sent a representative to the Austrian headquarters, to Field Marshal Sekendorf, to ask for emigration to Banat-Vojvodina as a means of salvation. Thus, in November of 1737, a large group of this tribe, together with some of the other tribes of the Great Highlands, about 4000 people,4 were sent to the regions of Rudnik, Nis, Mitrovica, Sremit, Karlovci.

In 1738, due to barbaric Turkish attacks in Valjeva, 3000 Albanians and Serbs were massacred and captured. This caused some of the mountaineers to return to their occupied lands, a group to join the Austro-Hungarian army, while another part remained in Serbia, where later in the years 1749-55 they concentrated in permanent residence in the villages of Hritkovci, Nikinci and Jarak. In these places, the Kelmendas stayed and preserved their language and ethnicity until the second half of the 19th century. With the entire surrounding Serbian Orthodox environment, they remained Catholic. According to the 1900 census, these villages had 4438 Albanian inhabitants, while according to a chronicle in 1921, 5 people still speak Albanian in Hritkovc and only 4 in Nikince. But in this now Slavized population, even today, the consciousness of origin remains unextinguished.

The Kelmedas who remained in Albania from 1737 (more than half of the tribe) continued the revolt against the Turks even after the withdrawal of the Austrians, just like the other hill tribes.

Punitive expeditions for the subjugation of the Kelmendas were also carried out in 1739, led by Ibrahim Pasha of Trebinje, and in 1740, by Sulejman Pasha of Shkodra, who had absolute superiority, but did not experience this success for long, because in this year he died. During the Austro-Russian war with the Turks 1787-1792, in which the Montenegrins also participated, with the exception of Piper, the tribe of Kelmendi did not support them. This exclusion came only from their antagonism towards the Montenegrins. These, together with the inhabitants of Kuč, with whom they almost always stayed together, this time stood on the side of Mahmut Pasha Bushatli, who, maneuvering between Austria and Russia, wanted to create an independent position against the Porte. At the time of the National Renaissance, among those men from Malësia e Madhe who participated in the Albanian League of Prizren in 1878, was the villager Ujke Gila, as the eldest brother of the four Bajraqs that Kelmendi had: Selca, Vukli, Nikçi and Boga. Especially during and after the Albanian League, the Kelmendas were among those tribes that stood up against the granting of Albanian territories to Montenegro. Their protests were also strong, against the so-called “Corti” compromise on the exchange of territories.

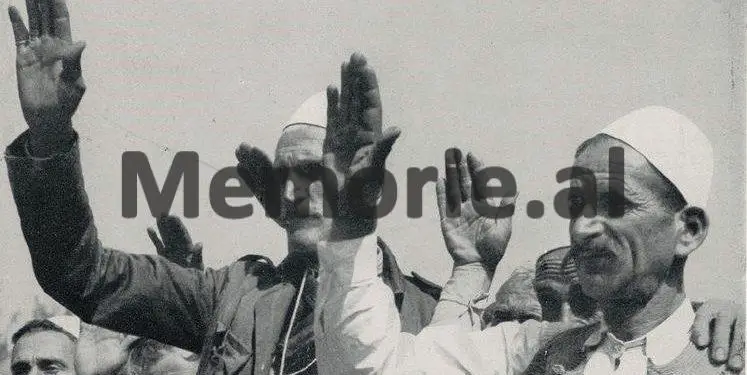

On March 24, 1911, Turgut Pasha, the commander of the Turkish expedition against the highland insurgents, declared some of the most honorable men of the Great Highlands to be traitors. Among them were Fran e Mirash Pali, Lucë Mark Gjeloshi from Selca. But all this, as well as many other threats and murders, which were made to this tribe by the invaders, did not deter these brave men from participating in the much-awaited joy, side by side with Hot, Grudë, Kastrat, Shkrel and Shale on the top of Bratila e Deçiq, on April 6, 1911, where by the order of the legendary brave, Dede Gjo’ Luli, Nikë Gjelosh Luli, Gjon Ujkë Miculi and Pjetër Zefi, raised the Albanian national flag. The Kelmendas were not left behind even in the Assembly of Gërce, which was held on June 10-23, 1911, at the height of the Malësi e Madhe uprising, sending as their representatives, Lule Rapuken from Vukli, Col Deda from Selca, Llesh Gjergjin , the bajraktar of Nikçi.

And so, the Kelmendas mountaineers, already, war after war, were dispersed and dispersed. Their number in their hometown in 1916 was: Selca 852 inhabitants, Vukli 712, Nikçi 685, Boga 228, a total of 2475 inhabitants. So important in the history of this tribe, was the time when the neighboring countries, as many times before, tried to occupy our lands. Thus, Kelmendi, namely the Paria of Boga together with other tribes, on July 2, 1919, signed the Memorandum that would be sent to the Peace Conference in Paris 61), where they clearly expressed their objections to the truncation of their ancestral lands. In the same way, together with other mountaineers, they expressed this dissatisfaction with the muzzle of their rifles, in 1920, expelling the predatory Serbo-Montenegro armies from these places, once and for all.

Finally, after the takeover of power in Albania by the communist forces in 1944, for the Great Highlands as a patriotic, freedom-loving and religious area, a new era of real mourning, devised by clearly anti-Albanian forces, began. Thus, on December 27, 1944, in the village of Ivanaj in Bajza, the men gathered in the house of Gjokë Tomë Kokaj, made their covenant to stand against red communism, which had been brought to Albania by Slavic agents. The entire Highlands almost rose to their feet and organized for resistance. Thus, Kelmendi was defeated by the villager, Prekë Cali, who on January 1 of the same year gathered his three bajraks: Selce, Nikç and Vukel, and with 150 men took a place on the right bank of the Tamara Bridge. For about a month, he stopped the advance of the so-called first Albanian partisan brigade, which, together with the Serbian-Montenegrin communist allied forces, wanted to conquer the iron feather of the Albanian race – the Highlands.

But the mountain braves, barefoot and naked, without food or drink, without proper weaponry, could not withstand the battles of the pro-Slavic red hordes for a long time. Thus, after the bloody battle of January 1945 at Ura e Rrjolli where the brave men of Kastrati, Hoti, Shkreli and Bajza 65) etc participated, and where the mountaineers suffered heavy defeats, a new ordeal began for them where hundreds they were shot with trial and without trial, from Kopliku, Bajza to the peaks of Vermoshi. As a sign of revenge to bring the highlanders to their knees, this year, in Shkodër, exactly in Zall i Kiri, Kelmendi’s brave 78-year-old husband Prekë Cali was shot. According to the report of the head of Shkodra Defense, Zoi Themeli, during this wave, 44 Kelmendas were killed, 21 were wounded, 3 others were shot, because they were collaborators of Preke Cali; 34 houses were burnt. So, this tribe this time was burned by the Albanians themselves.

In the end, it is noticeable that, in the year of Albania’s independence in 1912, Kelmendi already counted 2,475 people, and that 3% had accepted Islamization. Nikçi was Islamized the most among the brothers from Kelmenda, up to 10%.67). Against those bloody five-century wars, and various pressures: heavy taxes, janissary, taking slaves, inhumane torture, physical liquidations, etc., this tribe, as well as other Albanian tribes, although crushed, managed to survive, no one else a few more, preserving the pure ethnicity, the ancestral religion, which gave light and life to the nation. In the end, we say that the tribe of Kelmendi, as an important member of our people with an amazing organization and self-sacrifice throughout the past, even against the injuries of the population that had, fought and lined up countless victories, internationalizing even more very much our cause and showing the Ottoman government, as well as the Balkan powers that the lands of the ancestors and the ethnicity, will be preserved at the price of life as the eyes of the forehead. Memorie.al