By Arben P. Llalla

Part Eleven

Greek Collaborators, Projectors, and Leaders of the Genocide in Chameria (1944-1945): The Truth about the Collaboration of the Chams with the Germans

PREFACE

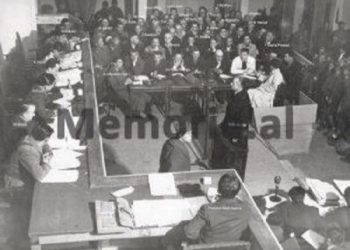

Memorie.al / The period during which I started writing the book was from 2008-2016, gathering materials little by little. It was very difficult for me to find original photographs and some Greek-language newspapers for the years in question. For about 70 years, the Greek state, with its state structures, has been feeding domestic and foreign public opinion with books and false writings about what actually happened from 1936-1945, concerning the Albanian minority in Chameria-Southern Epirus.

Continued from the previous issue

APPENDIX

Racism against Minorities in Greece, particularly Albanians and Slavic-Macedonians

The issue I will present concerns, in a nutshell, the expulsions of Albanians from 1913-1945 and Slavic-Macedonians from 1946-1949 from Greece. I think it is an interesting and difficult topic, due to the fact that the Greek state has not yet opened its archives for these cases. On October 16, 2008, according to the media, the former Prime Minister of Greece, Kostas Karamanlis, set a deadline for re-mortgaging all properties in Greece. This issue directly affected the property titles of Albanians and Slavic-Macedonians of the Aegean.

This concerns the assets of the Cham population, whose real estate is held hostage by the Greek state with the so-called “conservative seizure,” as well as the Slavic-Macedonians of the Aegean, who were expelled during the Greek civil war in 1946-1949. As is known, both the Chams and the Slavic-Macedonians are prohibited from seeking their rights under international law, the return to their lands, and compensation for the assets used by the Greeks to this day.

The directive, approved quickly in 2008 by the Greek government, with a deadline until October 16 to submit documents for re-mortgaging properties, seems more like a stab in the back to hinder Greece’s two neighboring countries, Albania and Macedonia, which in some way depend on the Greek signature for membership in the EU and NATO.

The Greek government’s decision in 2008 seemed tendentious, based on the fact that the Greek state prohibited Chams and Slavic-Macedonians of the Aegean from obtaining visas to enter Greece during that period, and thus they would not be able to mortgage their properties.

An Albanian and a Slavic-Macedonian, whose relatives were forcibly expelled from their lands by the Greek government after World War II, must first open a case in the Court of First Instance of the city where the property is registered to begin procedures for the return of the property in Greece, which they claim to own.

Absurdly and ridiculously, the claimant is required to be represented by a lawyer, who must be Greek. If the right is not resolved in the Court of First Instance, the case proceeds to the Second Instance and the High Court.

Given the many obstacles, such as the bureaucracies of the Greek embassy that prevent the issuance of visas for this category of citizens, and the length of judicial processes at the time, the properties of Albanians and Slavic-Macedonians were permanently appropriated by the Greek state, as they could not be registered by the deadline of October 16, 2008.

Thus, once again, Greece, a member of the European Union, NATO, and many organizations that protect human rights, showed that it is a state that violates these rights. The history of human rights violations in Greece is painful and has its beginnings in the first years of its independence in the 19th century.

Racism against Minorities in Greece

Greece has not had a Middle Ages, a Renaissance, or a war of resistance against the Ottoman invaders. After the fall of Byzantium, it was always inhabited by Albanians, Jews, Turks, Romei (Greeks, centuries ago, preferred to be called “Romei” rather than “Elenas” or Greek), Slavic-Macedonians, and Bulgarians, who, after being selected, formed the Modern Greek state with a fraudulent mythological history. The fact that Albanian, Turkish, Hebrew, Slavic-Macedonian, and Bulgarian are spoken in family circles in Greece shows that there is still an unassimilated population, even though state oppression has been and is savage.

Most Jews lived in the city of Thessaloniki, where Europe’s largest cemetery once was, with over 500,000 graves, but the Greeks destroyed this cemetery and built the “Aristotle” University with the marble slabs. So, where thousands of young people study in Thessaloniki today, the Jewish cemeteries used to be. During World War II, the Greeks handed over most of the Jews to the Germans to be sent to isolation camps.

Out of about 56,000 Jews that Thessaloniki had in 1941, when the Germans occupied it, within a few months, 54,050 of them were sent to concentration camps, i.e., over 96% of the population of this minority. Today, the Jewish community in Greece is not officially recognized and has only a small cemetery in Thessaloniki, maintained by the state of Israel.

In the early 1980s, Greece also destroyed the cemeteries of Albanians, Bulgarians, and Romanians in Thessaloniki. These cemeteries were the property of these communities. The Bulgarian minority has been assimilated; only a few hundred elders still live somewhere in the Seres area and speak the Bulgarian language.

Greece has been gradually reducing the Turkish minority. The Turks who once lived in Thessaloniki are almost assimilated. They mostly do mundane jobs, selling tea, salep, and bagels from pushcarts. These Greek citizens of Turkish origin, whose mother tongue is Turkish, live in some shacks in the corners of the streets of the city’s old neighborhoods.

Turks living in Evros-Thrace are known as Greeks of the Islamic faith and not as a Turkish minority. This population of the Islamic faith, who call themselves Turks, managed to be represented in the early 1990s with three deputies in the Hellenic Parliament, but these deputies have always been known as Muslims representing Greek political parties.

The Vlachs in Greece are the most pampered minority in terms of power, but their linguistic and cultural rights are not recognized. They are known as Greek Vlachs (ellinovllahon). In many cases, the Vlach population has seized the assets of Albanians and Slavic-Macedonians, after they were forcibly expelled from their homelands.

Violence against the Albanian Minority 1913-1945

With a racist skill, the Greek state has systematically expelled Albanians from Greece since the end of 1912 and the beginning of 1913. This refers in general to Albanians of the Islamic faith. But even those Orthodox Albanians who refused to declare Greek nationality were massacred or expelled from their homes, to live in cities deep within Greece to be assimilated faster.

The Albanians who were expelled and were Greek citizens were first stripped of their Greek citizenship and declared missing, people without an address. Furthermore, their assets were appropriated and given to others. Orthodox immigrants from Asia Minor were settled on the seized lands. The properties appropriated by the Greek state from Albanians are divided into two categories:

a) Albanians whose property was unjustly appropriated by the Treaty of Lausanne as an exchangeable population of Muslims with Orthodox Christians.

b) The Albanian Cham population, who were called collaborators with the German invaders by the Greeks.

By decree-law of the years 1923-1932, Greece appropriated all the assets of Muslim Albanians, under the pretext of the Treaty of Lausanne, as an exchangeable population between Islamic Turks and Greek Orthodox Christians. This idea found support in the circular of the Greek Ministry of Agriculture, dated October 1, 1922, which ordered the general administration of Epirus that “…refugee families should be settled on the properties of Muslim Albanians” (AYE/A/5 (9). (General Governor of Epirus, Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ioannina March 2, 1923).

In the main centers of Chameria, such as Filat, Paramithi, and Margelliç, special offices were created to nationalize the properties of Muslim Albanians, (Conference de Lausanne sur les Affaires du Prache Orient, 1922-1923).

In early 1926, in Geneva, the President of Greece, Theodoros Pangallos, made an official statement before the League of Nations, with which Greece recognized the Albanian minority and no longer called the Mohammedan Albanians living in its territory a Turkish population. Among other things, he stated: “The independence and status quo of Albania are of great interest to Greece, because its policy is the basis for maintaining peace in the Balkans…!”

The thesis that has been held by us until today, that Orthodox Albanians are Greeks, is wrong and kicked out by everyone. Since it has taken a turn for the worse and reached the point of exhaustion, I took the necessary measures and dissolved all the northern-Epirote societies that embodied the most extreme corners of this sick thought.”

On January 18, the Albanian ambassador in Athens, Mit’hat Frashëri, received a promise from the Greek Foreign Minister that he would personally deal with the issue of the Cham exchange, while Mr. Pangallos himself declared that the Muslim Chams would be excluded from the exchange process.

A month later, in February of the same year, the decision to exclude all Albanians of Epirus from the measure of forced exchange and amnesty for the Chams accused of political propaganda was officially announced, thus providing a final solution to the issue, a solution that certainly absolutely satisfied the Albanian side.

The declaration of the President of the Hellenic Republic, General Theodor Pangallos, to exclude the Cham Albanians of Epirus from the exchange measure between the Turkish Muslim population and the Greek Christian population, was decisive for the course of all issues. The content of the issue shifted from determining the origin and national identity of the Muslim population of Epirus and from their inclusion or not in the measure of forced exchange, to the process of their inclusion in the Greek state and the respect or not of their rights by the Greek authorities.

Thus, from the “Greco-Turkish” issue, the topic now concerns Greco-Albanian relations, which will also have a very high degree of influence in the future. The presence of Muslim Chams in Epirus constituted a special case and a strong document of negotiations that the Albanian government aimed to use to achieve a satisfactory normalization of its economic objectives, as far as the property issue was concerned.

But the issue of Albanians in Chameria would not be resolved even though Greek diplomats and politicians promised. In the following years, the Greek state, in the name of the agrarian reform of 1925-1927, denied the right to agricultural land to all those people who did not have Greek nationality. Italians, French, Germans, and Turks who had properties in Greece were compensated, but only the Albanians were not compensated. A few years later, World War II would begin. With the capitulation of Germany, the Greeks resumed massacres against the Albanian population in Chameria.

The Cham Albanians who were expelled in 1944-1945 were called collaborators of the Germans by the Greek state, and collectively their Greek citizenship was taken away, and their assets were appropriated. With some primitive laws, Greece denied any human right to all those Greek citizens who had not accepted Greek nationality, to ever return to Greece, even as visitors.

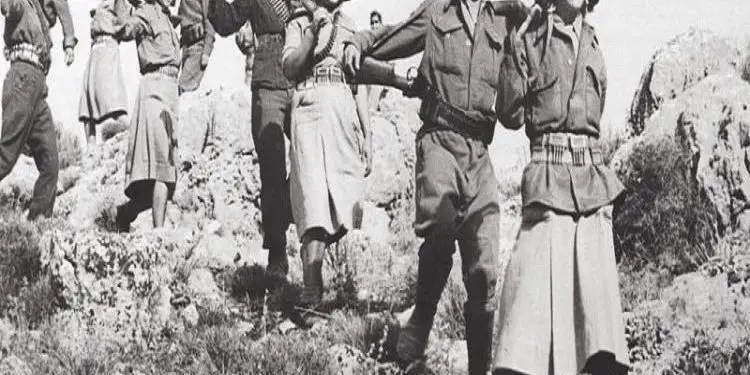

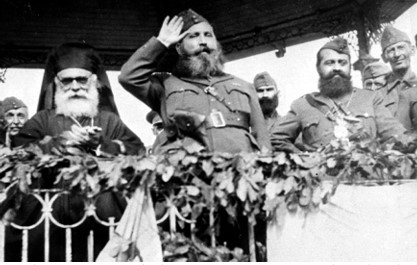

During the Greek civil war for power from 1946-1949, between the right-wing and communist forces, the Albanians of Greece who were violently expelled in 1945 by the EDES forces led by Napoleon Zervas were also mentioned. From the historical documents, we single out the requests of the head of the Greek Provisional Government, Markos Vafiadis, who presented among many requests to Enver Hoxha to enable the expelled Chams to line up in the Greek Democratic Army, which was led by the communists.

On September 24, 1947, Markos Vafiadis came to Tirana in a hurry via Korça, as the head of the Provisional Democratic Government, to ask for help. Markos, asks Enver Hoxha to send Chams expelled from Greece to Mount Gramos, to fight alongside the Greek rebels…

Markos Vafiadis came to Tirana without any prior notice. For this reason, Enver Hoxha did not meet him but assigned a member of the Political Bureau to talk with him. During the meeting, Markos Vafiadis presented the following requests to the Albanian government:

- To send 3,000-4,000 Chams to the Greek Democratic Army, from the 18,000 who lived in Albania, expelled by the forces of Napoleon Zervas.

- To organize the 25,000 Greek refugees, most of whom were of Macedonian ethnicity and were in Albania, into 3-4 centers, to be sent to help the Greek Democratic Army.

- To continue the shipment of armament and in the shortest possible time to send 10-12 cannons.

- To examine the prospect of economic aid, with food and clothing for the Democratic Army.

- To eliminate existing mediations until direct links are established.

As for the Chams, the Albanian side considered that they could not be a factor of help. The Albanians from Chameria would not want to go to war. But even for those who would want to fight alongside the communist forces, there was a risk of falling under American influence. For this issue, the answer was given that: “for the time being, this is not possible, taking into account the interests of the Greek Democratic Army, but they would do what they could to help at the right time, with what they had the opportunity to…”!

According to the data, the Greek politicians of the time admitted that the Chams had been expelled from their homes in Greece by the racist forces of Napoleon Zervas. In the request of the Greek democratic government, it is accepted that about 18 thousand Chams were expelled, but in fact, this number was larger. The important thing is that mass expulsions are accepted. Markos Vafiadis was a well-known politician, who, after living for about 23 years in the Soviet Union, returned to Greece in 1983. In 1989-1990, he was a deputy in the Hellenic Parliament for the PASOK party. / Memorie.al