By Keze Kozeta Zylo

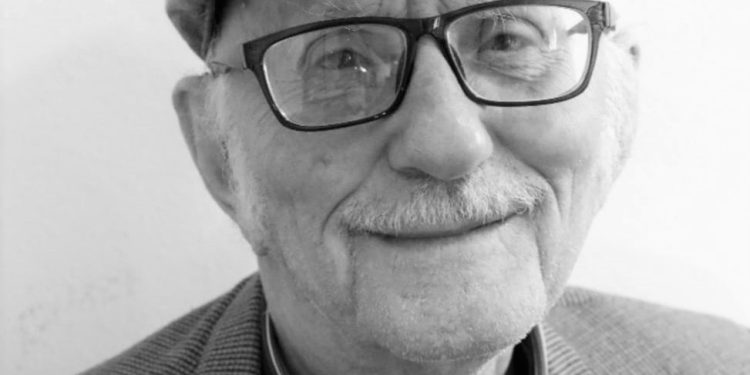

– Conversation with the former political prisoner, the distinguished 95-year-old painter, Mr. Lekë Tasi –

Memorie.al / “My longevity as a 95-year-old may be connected to the will of God, allowing a person to pass on a certain testimony to their descendants…”! Talking with Mr. Lekë Tasi, although we are separated by seas and oceans, is a unique and very special pleasure. His story is one full of pain, almost unbelievable, but the artist knows how to skillfully convey it, as he has lived it himself, and his culture as a true erudite is astonishing. Although he is 95 years old, I must say it is a pride to have a polyglot intellectual like Lekë Tasi among us. I met him at “Vatra” during the promotion of the memoir book “Grabjani by the Hills.”

A book with an unparalleled, heart-wrenching narrative. All 506 pages are rays of light that illuminate the darkness and denial that has been inflicted upon this breed like Lekë Tasi and his extraordinary family. For your curious reader, about this illustrious national figure I leave you with his personal account as he responds to my questions.

You have celebrated your 95th birthday this year; how do you feel at this age? Many of my friends of the pen and readers, when I told them that soon you would have an interview with Mr. Tasi, wrote to me that they are surprised by your age, as you speak and appear anywhere with a brilliant memory. What is the secret?

Longevity is a fact, a fate independent of our will, but it can also be related to the will of God, to allow a person to convey a certain testimony to their descendants…! Regardless of how credible it may be, I have felt this task upon myself, which is why I wrote the book about the sufferings in internment and encourage my fellow sufferers to do the same.

What was your childhood like?

I had a happy childhood. We lived in Athens as a family.

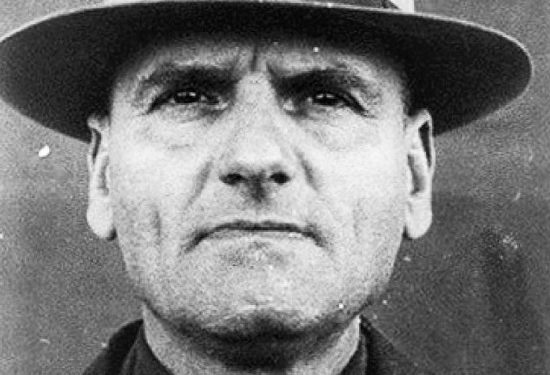

You are the son of Koço Tasi, a lawyer by profession, and a member of the First Albanian Parliament after the Congress of Lushnja. What are some of your memories?

I remember my father constantly walking around the room, preoccupied with something, while I was focused on playing. Later, I understood that he was thinking about the place of his childhood, how to return, because at every festive occasion, he would repeat to his friends: “Let’s go to Albania”! But he did not think about returning like any ordinary immigrant, but through a change of the regime there.

In fact, two attempts at insurrection are linked to this desire of his, in 1926 and 1931, unfortunately failed attempts, but also a risk he endured with two bullets from an attempt that fortunately grazed him, one hitting him in the flesh while alive, but with no damage. The danger occurred when I was 6 months old. As I grew up, I thought I needed to understand more than anything what drove my father to engage in dangerous work, and what’s more important, whether to accept or not this kind of life.

He accepted it, and in fact continued, as after we were repatriated on August 15, 1941, he went as an inspector to the Prime Minister’s Office in the newly liberated Kosovo to govern it. This was his duty, in constant parallelism, in polemic with the Italian fascists, who took advantage of his independent stance regarding the murder of a fascist federalist, where my father ordered a thorough legal investigation, contrary to the act of terror that they wanted, and thus he was surrounded in a café where he was conversing with the prefect of Peja.

He was saved from this danger (would it be the second case of such punitive action within weeks) if a group of Albanian gendarmes had not rushed in, thus surrounding the fascists who did not insist. From this episode, and also from the fact that the government of Mustafa Kruja in Tirana, similarly desiring more independence, had come to an end from Pariani, my father was dismissed from his position, but he was alive. Meanwhile, the communists did not recognize such nuances. “Have you done anything for Albania, and especially for Kosovo? You deserve life imprisonment,” they told him. This happened in 1945, during the “Special Trial.”

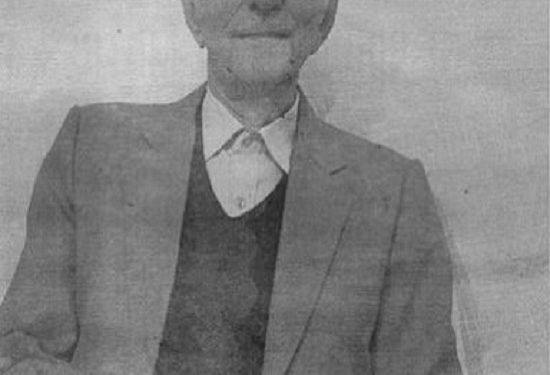

“Your arrival at ‘Vatra’ was an honor for the Diaspora and ‘Vatra,’ as you are the nephew of the political prisoner, Akile Tasi, the Minister of the Albanian State, a close collaborator with Fan Noli, Faik Konica in the ‘Vatra’ Federation, as well as with the newspaper ‘Dielli.’ What do you remember and how have you experienced these dramas in your family?

I first met my uncle, Akile Tasi, in Përmet in 1941 when I returned from Athens. I was 12 years old, and being the most delicate of my siblings, my father took me with him to the first excursion, leaving the other children, Napoleon, Tefta, and Ylli, for later. A few weeks later, during which we ascended high in Dhëmbel, above Shen – Elena in Lipa, he showed me the peak of Tomorri, which was white with snow.

I also remember him in Shën Mëri of Fushë, trying to identify the name of some ancestor on the gravestone. He had left home at the age of 14, secretly escaping to America, and now he longed for the old days. Since I have spoken at length about my father in the book “Grabjani by the Hills,” let me elaborate more on my uncle here. After 30 years of staying in the USA, where he was involved with “Vatra,” during that difficult initial phase, also serving as the editor of “Dielli,” he returned to Albania and was eager to contribute.

I later understood this from bits of conversations. In fact, he took me with him to Korçë and Tirana to help me form a perspective on the more significant issues of the newly reclaimed homeland. I was indeed very young, but I listened to the conversations he had with the intellectuals he met in those two cities. For instance, I learned that during his several years as the director of the National Library, he was interested in archaeology; it was a time of excavations and attempts to create a national theater.

I know from several translations from English (works with one act) that I have in manuscript form, where the patriotic theme predominates, and perhaps some of them may be valuable in the future. The most valuable of which is the story “The Happy Prince” by Oscar Wilde, which also reflects the spiritual orientation of the translator. He was willing to help anyone from the prisoners who had the will to learn a foreign language. But he died of cirrhosis after 17 years in prison, and his remains have never been found.

You are an artist, a political persecuted person, and a relative of missing persons, as your uncle’s remains were never found. What have been some of your efforts to find your uncle’s remains?

Finding the remains is a primary task, not only to honor every human being who dies (especially those without guilt but even those with guilt) but above all to ensure that the governments that come after inhumane revolutions deserve the name of a legitimate state. This task has not been accomplished, despite recommendations from the civilized world, due to the extreme malice of our Enverist dictatorship, as well as the accumulation of numerous problems faced by the subsequent governments.

As a family, unable to conduct searches (in fact very few of the thousands of families whose loved ones were executed were able to find their remains), we decided to place the name of our Akile on the gravestone under which my father and brother rest, thus resolving the matter with a cenotaph, while waiting for science to solve this legitimate request in the future, with its means.

How has the European Parliament, the Institute for Democracy, etc., helped in the “Days of Remembrance,” to acquaint the public with the crimes of the dictatorial system, and what is your comment on society’s reflection on the past?

In my opinion, external pressure must continue, because the main thing is not the concrete realization of norms, but the respect for the norms themselves, how respected they are in a society where, due to overwhelming force, these norms have been violated, without this violation being a historical practice. The issue is to return our society to its humane values, without any tolerance for the neglect brought by time…!

You have been in an internment camp for 15 years, working as a cooperativist; please speak to the many readers about the lifelong violations, the deprivation of freedom, and the conditions you lived in?

After three decades that have passed since then, I can say that that work period in the village deserves to be studied not only for the backwardness of the economic system but also for the psychological reactions it caused, a whole apparatus of hypocrisy that upheld the dictatorship but also consumed it day by day. It is a matter of working in the deep layers of human consciousness, where intuition must work harder than the testimonies of those interviewed.

No one can boast that they will be sincere when telling their own tricks to evade pressures, much less their illegal gains at the expense of their comrades. The system we went through had the name socialist, but it was more antisocial than history has ever seen. The living conditions were difficult, especially those that involved proximity to neighbors (long queues at the store, cotton picking, envy toward a comrade’s good position in harvesting, etc.). A person can adapt to the difficulties of nature, but never to the unpredictability of the person next to you.

“You were the first cellist in the Radio-Tirana Orchestra and the Theatre of Opera and Ballet, where you were dismissed for political reasons in 1967. What do you remember from those years of your art with the cello?

That 20-year period (1946-1967) was the most comfortable, not only due to youth, which nurtures hopes and illusions, but also because of the still “innocent” phase of society, within the orchestra and in Tirana…! This was perhaps also due to the poverty of the regime’s resources. It did not yet know the depths of treachery it could find among the citizens, as long as it increased its pressures. The subsequent deterioration of the economy led to that path strewn with resources, whether in filling the mines with innocent boys or in finding agents of repression who tormented them.

What has your life been like after the ‘90s when you were freed from internment? How did you experience the arrival of democracy and the years of transition?

It took several years for me to realize the reality that stood before me. In fact, this deepening still knows surprising phases regarding how uninformed we had been. The newspapers are revealing it to us, and for me, this is the best and most outstanding news, I would say. In short: when two decades after the ‘90s, this opening of the files was not verified, then we must establish a clear division between the political elite, and we must conclude that whoever desires this opening and continues it, will have something to offer the country.

There is one test: Who stands in favor of a new Western-type justice, recently established, and accepts to put it in place, and who seeks conveniences or accuses for bias to avoid judgment. The drama is ongoing, but it is a drama we have never seen until yesterday. Indeed, the hope is to also scan history. For me, we are within a comprehensive clarification process that is happening with the support and backing of the Western factor, which has often monitored us closely. Now it guarantees us, and no one can stop it.

Thank you very much, esteemed Mr. Lekë Tasi, for your interview!

I congratulate you and wish your children a wonderful career! Memorie.al