By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirty-four

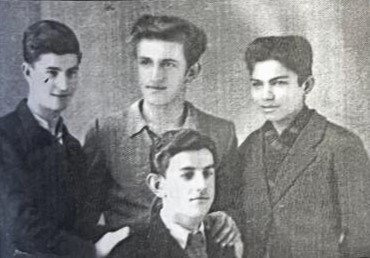

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

Anyone who sees them tortured makes an impression, but the case of a former teacher is different from all others, as for a special respect that he enjoys for life from his former students.

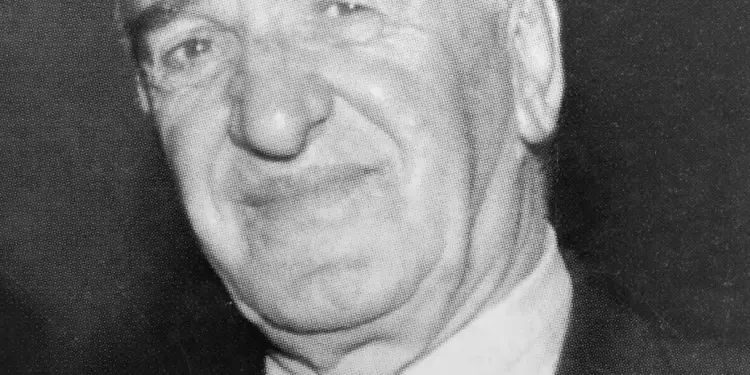

Mr. Qazim was one of those teachers who, among other things, had created a real sports yard in the Perash School, with fields and equipment for all types of sports, such as football, basketball, volleyball, as well as an athletic track and field. Without dwelling on the great work that he had done not only with students, but also with many well-known athletes and sportsmen of the city, it is worth remembering that the representative team of that elementary school, dressed in regular sports uniforms since that time and, under the leadership of Mr. Qazim, successfully competed in football matches with the lower classes of the gymnasium. Mr. himself Qazim, for many years, had been a prominent football player for the “Vllaznia” team and the man who had brought the game of basketball to Shkodër from Harry Fultz’s school. Until he went to prison, he was considered the best Albanian referee, and the 1946 Balkan Games, held in Tirana, would confirm that once again.

Among other things, I would remind Mr. Qazim of the walks that he took us on in the spring, when he, together with other teachers from our Perash School, would take us through green meadows and up into the hills. I would remind Mr. Qazim of these and other things, while I saw him in that pitiful state in which they had found him, with the bottoms of his pants as if they had been eaten by mice and around his knees so pale that even flesh was visible.

But somewhere near his dungeon, there was another citizen who was suffering from severe nervous breakdowns due to despair. Often during the day he would imagine that he was in a war, and imitating the sound of rifles with his mouth, “bam-bam”, “bam-bam”, he would continue until he got tired, so that his imaginary fight of several minutes, but repeated for the first time during the day, would end with a “baaaaa”, somehow a flash. In addition to the above, I would also be impressed by a distracted and tragic look in this man, which seemed to emit sparks.

Regarding the two prisoners above, I had carved on one side of a hazelnut a pair of torn trousers, which would remind me of Mr. Qazim, and on its other side, a long rifle, which would remind me of the unknown prisoner. They had brought an old man from Mirditet to my cell that day. From what I heard from the explanations he was giving to an officer one day, he had been imprisoned after he had killed with an axe an officer who had been in love with his master’s daughter, to whom he had been a servant for several years. All those days he would pass calmly and whenever any investigator asked him about the murder he had committed, he would talk about it without any shame and apparently without considering the consequences that would come from it, as if it were an act that, according to custom, he had been obliged to commit. But in his last days, he was playing with his mind and, among other things, he would shout at the top of his voice: “Look, look, he’s riding. Christ on a donkey”!

After he was sentenced to death, his mind was enlightened once again and he would be very calm when he left the body and sleeping clothes, leaving the trusts to distribute piece by piece to some of his poor friends, as he had himself, naming them with two surnames, such as, for example, Llesh Hilë Zefit, Ndue Frrok Pjetri etc. Even this victim of tradition, as part of the diary, I would fix on a hazelnut page through the number 11, which was the number of his dungeon, and on its other page, one as an oping.

Selman Disha from the village of Doma i Postrriba

One early afternoon, when the policeman on duty named Mërkur asked the prisoner of dungeon no. 15, what his name was, I heard that the answer was; “Selman Disha”, and when the policeman asked him where he was from, I again heard him mention the “Dom” canton. So, starting from that day, I knew the name and the place where that old man was from, whom I had been following through the door hole for a long time with a feeling of pity, and this, not only for the pain he caused me as the oldest who should be in that prison, but also for some fine and noble features that his small face had that seemed a little sharp, that they would speak to me as if he were a good man.

Mercury, a brown policeman who was generally well-behaved and who by nature seemed to be indifferent, that day, perhaps trying to shake off the lethargy and sleep that had taken hold of him after lunch, made three or four quick laps through the corridors, – since he did not know what to do – and went to open the door of the dungeon closest to his place of service, a dungeon in which happened to be the political prisoner, Selman Disha, an old man from the village of Doma. To make fun of the shy Selman, Mercury had placed the muzzle of his automatic rifle on the door and was scaring him, telling him that he would kill him. From a distance, I could not understand Selman’s words, but as a gentle man that he must be, he was seriously frightening them.

In a very thin voice, he was begging Merkur for something, for something that I couldn’t quite grasp. However, I was moved by Selman Disha’s fear and could barely contain myself. The only thing that was delaying my intervention with Merkur was the fear of discovering the hole I had in the door. As Merkur continued his game with Selman, I could not stand it any longer, and in order to free Selman from him, I knocked on the door two or three times, until I was sure that Merkur was heading towards my dungeon. As soon as he opened the door for me, he asked me calmly: “What’s wrong?” He didn’t take offense when I told him as much as I had thought and he left without giving me an answer, and without even going to Selman Disha.

A few days later, again early in the afternoon, I thought I heard a man crying in a thin voice. At first I had the impression that he was trying to hold himself together so that others wouldn’t hear him, but after a few minutes, apparently out of fear or longing for his own, he became so weak that he soon dissolved into an unstoppable, pitiful sob.

I thought that maybe the prisoner was Selman Disha, but I wasn’t sure. There happened to be a policeman on duty who seemed a little old, but he was also lazy, because he never left his place, and in this case, unable to tolerate the prisoner who was crying behind his back any longer, he rushed to the counter and asked him angrily: “What are you crying for?” It would have been Selman himself, who, crying even more, would have answered him: “I’m afraid my son is dead”!

Malsori Selman Disha, for his age, must not have thought about himself for years. He happened to be alone in a prison cell, and apparently his mind had gone to the worst thing, that is, that his son had died. If he had seen him, he would have been nothing but, as they say, “a handful of bones”! Only a communist government could have considered him a dangerous man, called him an “enemy of the people” and, before sentencing him, kept him for months in a Sigurimi dungeon under investigation and torture

To remember the above, I had carved on the side of a hazelnut a square with a cross inside it, to remind me of the window where Selman’s two dialogues had taken place in turn and below, the number 15 of his dungeon. During the following period, relatively calm, I had also created four poems, which more fully reflected my spiritual state and my dispositions of revolt, whose titles, in turn, had been: “To Mothers”.

“To our Mothers”

“Freedom to Forgive” and the last erotic one; “spring and Longing”! To remember them, I repeated them every day, and eventually the first two, as the most repeated of them, managed to partially escape oblivion, while the last two, as if created on the eve of the resumption of torture, would emerge from my memory.

The remains of the two poems are:

TO MY MOTHER, OUR MOTHER

“Your big eyes

Colorful and like oil,

Closed in a cell,

Shocked by a scythe,

Darkened by blindness,

Rubbed by rotten moisture,

I feel like I’m seeing them for the first time

I saw them, my dear mother.

IV

I looked at one eye, mother,

The knee you gave me,

I didn’t come out alive,

Have you forgiven me?

The water is gone,

My body is all wounds,

Mother, oh!

There is no blood,

I am free from freedom.

III

Hymns will be sung around the flag,

As long as the earth shakes,

To the sky and somewhere beyond,

To the mothers, let it be said, that the mourning is no longer there,

For “The body is broken, stop crying”

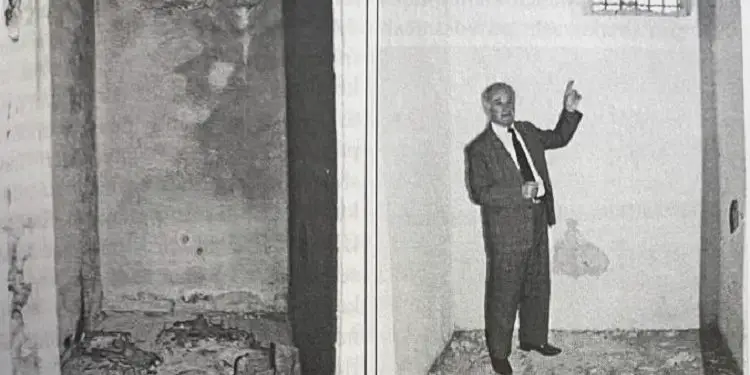

From the dark dungeon No. 9, they take me to the one with No. 2 towards the light. It was a day in the first week of July, when in the morning they took me out of dungeon No. 9, and took me to the one with No. 2, towards the light. I had become so accustomed to my dungeon No. 9, which I was leaving, that it constantly seemed better to me even though it was dark and damp. The regret that I was changing dungeons lasted as long as it took me to wrap up my sleeping clothes, plus the path of about five or six meters, which separated one dungeon from the other.

As I walked into the new dungeon, I was very surprised by the light that had poured in there without sparing, so much so that from surprise and joy, I was probably barely able to refrain from uttering an exclamation that could be expressed with a long; baaaaaaaa! That small window there, high up in the ceiling, would probably not have been enough even for the dungeon itself, but since I was coming there after six months of staying inside a dark dungeon, it seemed very bright to me, and beyond it, the clear and pure light of a summer day, a miracle. The first thing I said to myself as soon as I found myself inside it was:

“After all, prison is prison! The real one is over there in the corridor, on the dark side”! The policeman had closed the door and left, while I, still stunned by what I was seeing, continued to stand on the sleeping bags waiting to be spread out, and I looked towards the window high up in the ceiling, from which not only white summer light entered, but also a clean and fresh air, which seemed to be entering me from somewhere directly into my chest, completely different from that of my “beloved” cell no. 9, with its heavy musty smell, which had constantly filled my throat and nose.

While I continued to stand as if bewildered on the bags, a flock of falcons quickly passed in front of the window in their agile and capricious flight, since this was also something unpredictable and important to me. For the first time I was realizing that there in cell no. 9, where I was no longer, my soul, from the darkness and stillness, because it had seriously begun to fade somehow.

After I spread the mattress against the wall, I began to inspect the new dungeon and very soon I fell into the footsteps of my unfortunate predecessors: the initials of the names of prisoners carved finely, but clearly, on the small surfaces of some black river stones, which had frozen into the plaster of the wall, like painful pages of anonymous diaries. Anything that the prisoner finds written by the prisoners before him, he will take as a greeting and a message, as a common fate that he has with them, and suddenly he will ask with his eyes: “Who was that man?” And then, he says to himself: “Does he still have to be alive? Where is that man supposed to be now? Did they torture him, or shoot him?” etc. etc.

In addition to the initials of the names, I would find full dates carved there, which were not accompanied by any other indication, leading me to many suspicious thoughts, such as: “Could the prisoner have wanted to tell the day of his arrest, or some important event that happened to him there, such as; an unusual torture, a death sentence, or the day when he was taken to be executed, etc., which the prisoners after him, as in my case, always notice with emotion.

Somewhere down the wall, I would see carved on the bright surface of a small, black stone, the initials XH.Q., which without a doubt, were those of my friend Xhevat Quku, with whom I was connected for a lifetime and everything. Suddenly, warm waves of longing swept over me, and memories after memories, as in fast-paced film sequences, passed through me before my mind, one after the other. I remembered everything, conversations, opinions and plans, including our eventual imprisonment, in which case resistance should have been categorical. Next to our prison there was an empty building, large and high, a real “shack” with only walls on the sides and a roof above, where sometimes they had brought the barber to cut and shave us, and where even the many swallows had built their nests.

Especially in the afternoons and until nightfall, I would constantly hear the joyful sounds of children playing until dark. Several times in the evening, I would take a seat in front of the window and as far away from it as possible, standing on tiptoe, in order to capture with my eyes as much of the space as possible of the firmament of the sky full of stars, the twinkling of whose mysterious, together with the general magic of the evening and its summer heat, would awaken in me somewhat special thoughts and feelings, becoming in some ways a daily and important part of my life in the dungeon. It seemed to me as if I had woken up after a long lethargy!

I was sleeping, and the fresh air that came in there without a break all night, I felt physically and was another special pleasure for me. If during the night I would fall asleep for a moment, I would turn to the other side with the joyful idea that a day like the one that had passed was about to be born again, that would bring light and air into the dungeon again and, with them, good thoughts, as well as a spectrum of memories that was coming to me more and more every day.

But, fortunately Unfortunately, those wonderful days would be few, and their fragile excitement would soon prove false, killing and dissolving them like the most ephemeral thing, because I would soon have to submit to an endless cycle of extremely difficult torture, under the constant and categorical demand of the Security: “trial” or “death”, when all along I had been asking for nothing more than a quick and honorable death.

Three months, between life and death!

My new investigator would be a cowardly and cowardly man named Ali Xhunga, who had come to Shkodra from the villages of Përmet with the low rank of aspirant, which showed that he had not even gone to war at the right time, despite the appropriate age he had. He was quite short in stature and when he happened to approach me, shouting and threatening me, I felt like bursting with anger, because I saw a bullet under him.

Short as he was, he sat in a chair, puffed up and puffed up like a rooster, and to give himself importance, he would take artificially serious poses. This career investigator, if he had not been more ignorant and brutal, as well as more criminal, would have been very dangerous for the victim to use to investigate him, for the sole reason that he was a coward and very submissive to his superiors. If something happened during the investigation of a prisoner, if the boss, for example, entered his office, he would immediately freeze and turn white in fear. As far as I am concerned, he lacked any personality, even the negative one of the criminal. Surely he was the type of a bad type of mercenary, who had been put at the service of crime for profit.

It would be investigator Ali Xhunga who would keep me hanging like Christ for three months, and as if that were not enough, on some occasion, he would also torture me further, in order that I would necessarily submit to the trial. “Trial or death”, – would be the motto of his criminal work with me. From the first day of the investigation until the last, he would leave me abandoned amidst the most extreme torture and death, a death that for a long time would be my only hope, and if I did not have a chance, it would be due to an inexplicable miracle of my fate.

When I was called for the first time by him, I found him waiting for me, sitting in a chair, serious and with an imposing posture, just as he must have thought of it beforehand. “Sit down,” he said coldly, and with the intention of intimidating me, he continued to remain silent and supposedly thoughtful for a while. Meanwhile, as usual, I looked at the calendar for the day and quickly noticed that it marked July 28, 1948, high up on the wall.

He seemed to be waving his hand authoritatively at me, saying: “I am the last investigator to deal with you. You will talk, but you will not get there, because you are young and you have a family, but in the end we do not ask about anything at all, not even about your life. How many men this country has seen! It amazes the mind, so think before it is too late!” The next day, he called me again and, further, angered by my calmness and silence, like the day before, he left his chair and approached me, speaking to me in a tone: “I know that you are waiting for your Anglo-Americans to come here, but know well that even if they really come, we will first slaughter all of you there, in the dungeons where we have you, dungeon by dungeon, one by one.” Memorie.al