By Dodë Bardhok Melyshi

Memorie.al/That was the last time my father and mother came to Italy. Sometime four years ago, or maybe five. This case I am talking about must have been around mid-January. One of those nights, very late after midnight, I woke up to the smell of tobacco smoke coming from the living room. It was two or three o’clock. Tobacco smoke has a bad habit, because it does not always go vertically, so it enters every space you find, even the horizontal ones.

My father, the big smoker, nor the categorical orders of the doctors, had not curbed this habit at all. I was never used to taking orders in my life, and that is probably where the excuse for not accepting comes from. To our insistence, he often recalled the doctor’s advice regarding cigarettes, he returned them with evasive answers, and in most cases, he closed the topic with a “sooner or later he would quit smoking”, which is in fact was one: “never”, clear this. And for this we had no doubt.

But that night I was surprised, because at three o’clock in the afternoon, he never smoked cigarettes, much less recently he smoked cigarettes indoors and with small children. It was compressive!

I got up and went to the living room. He had not illuminated it at all, he had lit only two, among those dim lights, which illuminate a little more than a candle, he was sitting in a chair, not far from the window, a large and long window, the length of which fell to on the floor, beyond her glass, she was looking out the panorama. It was a cold winter night, even though the inside was well beaten, warm, a full meal, I had never seen the dish so big, and the stars so bright and numerous. The cold of winter clears the air a lot, gives the opportunity to look far, far away, almost beyond the horizons.

To my short question, about this midnight awakening, he answered with one:

“I saw Zef in a dream”!

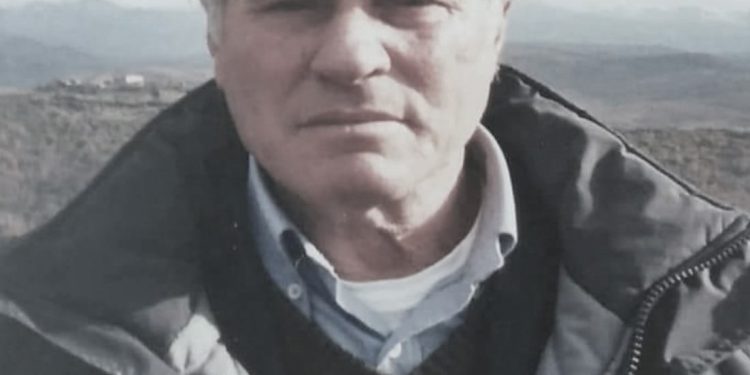

Meanwhile, he smoked a cigarette, the circles of smoke wrapped around his face, that wonderfully symmetrical face, which had the preserves and transported the charm of youthful times. My father’s eyes, sky-blue eyes, clearly expressing the whole charge of intelligence with which God had endowed him – were a little melancholy.

Dad, he had never conceived the complaint, neither the victimization, nor the justification in life. And perhaps he had ruled out melancholy in his youth, he should not have had the time and opportunity for it. Melancholy was becoming perhaps a luxury, of an age not already young.

“I’m making coffee,” I told him, and it happened. “I took another chair and approached him, sat down next to him, had two coffees, even though I did not want to drink it, much less lit a cigarette, and lit it, I who was with the tobacco” eternal “hostility”. But I did not find another way, to make my friend, to show solidarity with him.

And so, under the poison of that cigarette that at that hour of the night seemed even heavier to me, we began to talk to them in rare words tek-tuk, slowly- slowly, quietly, and looking both outside, there this winter was burning hard. The night was quite clear, so clear that it seemed to me that the eye was on the hills and even further the snow-capped mountains, which were miles and miles away, at the end of the endless fields of the city of Parma.

My father’s conversations have always been accurate, never a word out of place, never a word without weight, never a word without sufficient prediction of the outcome, while in recent years, he had put aside the constant dynamism of youth, and he became more patient and slower in conversation, and he seemed even more articulate. There was no way he could not be articulate, a man who, after 15-16 hours of tedious work a day, found time to read Shakespeare, or Saadi, or Petro Marko, or John Galsworthy . I never understood where he found time and peace, I read books, then…!

I did not ask my father about the dream, or about Uncle Zefi. He had told me the story of his uncle more than once. It was about Zef Dodë Lekgega, a former fighter of anti-communist resistance groups, in the clash with government forces in post-war Mirdita. He was killed in 1951. His body after death hung on a rope at the infamous “man of Lal Ndreu”, a large man who was located somewhere near where today is the museum of the city of Rrëshen. All the anti-communists who were killed from the Pursuit Forces, led by most of the Russian colonels, gathered there and hung in the man, with the sole purpose of terrorizing the people near the river of Zmesa, and the stream took them and drove them away, without a grave.

The grave of those bones was the water of the river or the sea, or the roots of the trees along the shores. My 9-year-old father had seen his uncle’s body, because the children who left the school, the school was then where it would later be called “Military Brigade” – they passed right next to “Lal Ndreu’s mulberry tree”. The trauma had been strong! Our father did not tell us this, but we learned it from others; had passed our nights and nights in a row shook them, just as it does not matter that a 9-year-old child can be shaken, in front of the body of his uncle.

In war you are killed, in war you can win but you can also lose, but the terrorization of the toads with the troops of the enemy, had never been done in the lands of Mirdita, for centuries…! I could not do anything without my sister, brother, or mother or son, hanging on the rope, guarding the police even after a decade, and I could not do anything…!

These thoughts pierced my head that night, with witnesses eating! Hana who reminded me of a verse by Fishta: “O moon, of one’s my moon”, – maybe Fishta had complained to Zana! Maybe Fishta did not complain, and it seemed so to me…?!

It must have been at that time, then, that in his childish spirit, rebellion against the system was molded. From the moment that the rebellion could no longer be neither active nor shared with others, it’s a passive, individual rebellion. It consisted of stubbornness, perseverance, without greed, face-to-face and tooth-for-tooth clash, with segments and people close to power, and more closely to the Internal Affairs Branch, consisted of survival and non-submission. Proud, terribly proud, even though people from time to time confuse pride with arrogance.

It consisted of the ability to be conscious, the master of the house of his people, impenetrable, almost a parallel system in miniature, with human and friendly connections, features, and immaculate habits, as opposed to an antihuman, even barbaric and devastating…!

Sometimes with intuition, sometimes with foresight, sometimes with retreat, sometimes with courage and aggression, always with himself, always with the god of his accounts, just when it was generally difficult for a man to be the god of his wife

A life of waves, collisions, fatigue and triumphs. Maybe the conspiracy in front of the hanging body of uncle Zefi, or maybe the conspiracy in front of the grave, much sought after and never found, of his grandfather, Major Bibë Dodë Mëlyshi, we killed cruelly by the soldiers of Tito and Enver, in distant Gjilan in in 1945, they made it possible for me to ferment rebellion and dignity at the same time…!

Heroes are often found in their daily lives, in things and details that at first glance do not make a fuss. It is useless to look for heroes in any books, or in any movies. They often hide and are found in front of us, silent, without vanities, and without great fuss.

In the light of a full inn, under the sky of the heart of modern Europe, on a long winter night, I was convinced that as we exchanged a few words, with our minds on distant Albania in time and distance , this Man to whom I approached with a chair next to him, was not simply my-father, but much more, the course of his life, had given him the dimensions of a hero.

A man with the attributes of great people, a life stamped and designed with letters of glory. Unrepeatable! Memorie.al