By KLITON NESTURI

Memorie.al / With his calm step, he enters the grass near the house and comes towards his favorite table. As always, Loredan Bubani is meticulous as “a German”. With his deep gaze and warm smile, he comes towards me, and as we meet cordially, we sit next to each other. We order a “Branca” coffee and drink and start the conversation, which, unlike other times, will be an interview.

What is the “triangle (of Bermuda)” of Loredan Buban’s life?

Buban? (Smiles) This is a beautiful question!… For me, the “triangle” within which my life is wrapped up has been the love for my family, friends and work. My life has been inextricably linked to these three essential elements.

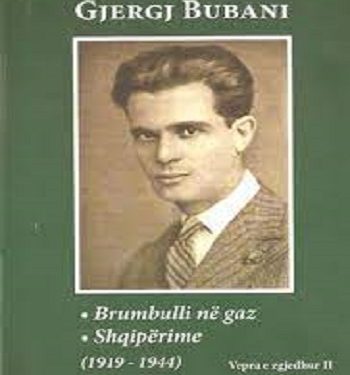

You are the son of Gjergj Buban, one of the most prominent publicists of the first half of the 20th century, the first director of Radio Tirana, translator and poet. How easy or how hard was it for you to grow up under the weight of your father’s name?

It has always been lucky for me to be the son of Gjergj Bubani. It is enough to mention and bring to mind his life, which you also mentioned, and I feel proud of the great legacy of his name and human values that he left behind. I was young, fourteen years old, when he passed away, and I did not know much about his activities, but I constantly felt the respect and adoration for him, from people who had known him closely.

And unjustly condemned, with the trials of time against intellectuals?

He was an unyielding man and this made him not to break even when he was heard in the “Special Trial” of 1945, even when he was sentenced to prison. Sick, in a serious state of health, they took him out, after he had served almost ten years of imprisonment, leaving him at the mercy of fate, as happened with many of his contemporaries. Until in 1954, he passed away at a very young age, 55 years old.

A heavy-weight name of Gjergj Bubani, how could you afford it?

I have felt the weight of his name even when I had to face many sacrifices in life, such as those of schooling, graduation or when I started working as a teacher in Rrëshen, and then as an editor. That’s why I fought to be the best at my job. It was not easy to have the shadow of suspicion and silent persecution following you from behind.

What qualities did you get most from your father?

I think that I got the rigor at work, the love for the family and the love for the Albanian language. While my brother, Dionysius, got the talent of writing and that of translations.

Your father, Gjergj Bubani, had a rich activity as a publicist, poet and translator, but until 1990, unpublished in a work. How did the realization of his work happen in 2007?

I have always been curious about my father’s work and real contribution. Gradually, he had grown on me in the form of a legend, from the accounts of others. Being also in the field of publishing, I was driven by curiosity to find the corpus and publish my own work. About this, we often argued with my brother, Dionysius; he started by nature, he thought that some articles in newspapers would shed light on our father’s contribution, while I constantly insisted on the publication of the work as complete as possible. That’s the only way we would know him, his sons, but also the Albanians. It was a debt that we had to fulfill for the sake of those living today, but also for those who will come after.

How difficult was the realization of his work?

It was a great job that was done to find, collect everything that he had published, written. Initially, I, together with my friend, Nermini, searched in the Romanian National Archives, thanks to the help of a cousin of ours who lived in Bucharest. Believe me, from the documents I found there, I was surprised by all the activity of Gjergj Buban, but also of the Albanian exile in Romania, mainly in Constanta and Bucharest. Endless publications, endless activities. An extraordinary asset.

But even in Albania, in the press of the time, there were enough of his publications?

Then, in Tirana, there was a very big commitment regarding the archives. For this, I am grateful to my friend, Halim Maloku, who has carefully reviewed every document and publication. He came from Durrës and sat for hours in the State Archives, being able to extract from there many old writings and publications. Also, I am grateful to my friends, Ndue Zef Toma and Mejit Prençi. After the proof of the corpus, we realized the publication together with the publisher Luan Pengili, to whom I am grateful for the dignified realization of the work of Gjergj Buban. Honestly, I am calm that now Albanians can recognize Gjergj Buban, through the written work he has left, journalism, poetry and translations.

Who was the person who stood closest to you throughout this commitment?

There were many people who stood by me in this commitment, but the main person who stood by me in my life was Nermini, the love of my life and my wife. We have been in love with him since we were young and from the first moment, we have not been separated from each other. We have been through many events together, many difficulties, we created a beautiful family with our two children, Ela and Gjergji. We have been with Nermi everywhere.

She came from the Dibran family of the Jegens, a wonderful family with traditions, while I came from a family in a way hit by the system. It has not been easy to face the difficulties and challenges of the time. Nermini, besides work, had to take care of his family more and at the same time live with the problems of my work. I thank Nermini for all the dedication and love he has given me. I don’t know how my life would be without him, but of course not so beautiful.

You mentioned Bucharest a little while ago. You were born in Bucharest and came to Albania very young. How did you experience going back to your hometown when you first went?

Yes, I was born in Bucharest in 1939 and I came to Albania three months ago. My father at that time was the director of Radio Tirana and we moved here. The Second World War and my father’s commitments made us stay here. Meanwhile, until the end of his life, my father corresponded with our cousins in Bucharest. For me, Bucharest was a legend, until the moment I stepped on it after many years, when the communist system fell. It was an indescribable thrill when I walked through its streets. There I also visited our house, the Bubans, which is located in the center of Bucharest, and everything related to my personal history and that of my family. For me, that city became and will remain dear, and every time I visited it afterwards, I felt happy and at home. In Bucharest, I also have the grave of my sister, older than me, whom I never knew, because when I was born, she was no longer there.

In your youth, you were also a speaker on Radio Tirana. Why didn’t you continue to live with the Radio microphone?

True. In 1969, at the Experimental Television, at the former Radio Tirana, a competition for program speakers was opened. I went and won. I gave the news show. At that time, we also did shows with Vitori Xhaçka, one of the first speakers in the history of Radio Tirana and a friend of our family. She helped me get to know the microphone and master it completely. I also remember my friend, Beqir Dërhemi, one of the first cameramen on that television. We worked for some time, but then it happened that I left Radio.

You have spent your entire life working with publications, first with the School Book Publishing House, and since 1997 with the “Omsca-1” publishing house. What made you enter this field in the first place and stay there forever?

The love for language and literature, as well as the tendency towards books, has pushed me into this “sphere”, as you call it. I first worked as a teacher, after my studies, but then with my commitment to newspapers and magazines, for language problems, I was appointed to the School Book Publishing House, in which texts were prepared for all levels of schools in Albania, since ” Primer” to higher education. We have faced a big, extraordinary job and I feel happy that, wherever I have been asked, I have made my contribution.

What was the text that left the most impression on you during the period in the “School Book”?

You can’t separate them. Each of the texts has its own beauty and difficulty. But I would single out my participation in the working group that was created for the drafting of the “Primer” under the direction of Professor Kol Jumari, with which many generations in Albania learned. Even today, from a scientific and methodological point of view, this “Primer” stands very high.

What do you think about “altertext” in school publications?

I am not a partisan of the “altertext”. I think that school publications should be unified and disciplined, starting from “Abetares”. Otherwise, children will not know what to learn and how to learn it, and we will raise a generation without a clear axis. Education and school are not business.

You are known as a strict editor, intolerant of the Albanian language and artistic values. How has it been for you to face the ambitions and selfishness of the writers who have passed their works “under your hands”?

In 1997, the publisher Luan Pengili, who had just opened the “Omsca” Publishing House, came to me at the School Book Publishing House, and asked me to work for his Publishing House. We talked for a long time and from the beginning we established a relationship of trust. At Luan Pengili, I liked his determination for work and the space he created, not only for me in my work, but also with all the staff who worked. So, feeling master of my work, I felt as free as ever, as responsible as ever.

From your experience, how do you think the publisher-writer-editor relationship should be?

Since the relationship between the publisher and the writer is a relationship of trust, the relationship of the writer with the editor is and should remain a relationship of trust. So have been the relationships we have built with the various authors who have published in “Omsca-1”, or even with other authors with whom I have collaborated. Everyone should understand that the book editor is not the writer’s executioner, but the guardian of the protection of language and artistic values, the cold eye, without which an artistic work cannot pass.

What do you think about translations?

In the same way, he also encountered the translators. In addition to the publication of Albanian literature, foreign translations occupied a large place in the work of Albanian publishers, so much so that today they occupy an important place in the book market. I have had the good fortune to edit many works translated into Albanian, and the challenge has been to make the work sound beautifully Albanian, while preserving the author’s originality and style. I was lucky to work with good translators. This also came from the selections we made with the publisher. We have not accepted weak translations.

How many published works have you signed as an editor?

I didn’t count them. It’s probably a lot, maybe three figures…

While we’re on the subject of language protection, what do you think of the language standard set by the Spelling Congress in 1972?

Absolutely for me it is the greatest achievement in the Albanian language. It should never be forgotten that language is what unites the nation. All civilized nations have established a language standard and I am glad that we have one too. Imagine what we would be like today if we hadn’t set the standard; we would write and talk among ourselves and we would not understand each other. Nor would literature be what it is today. Were mistakes made? They are done. The important thing is that the language is always in the process of development. It is up to linguists to document it and writers to enrich it, even with dialect forms. In the end, it is time that chooses.

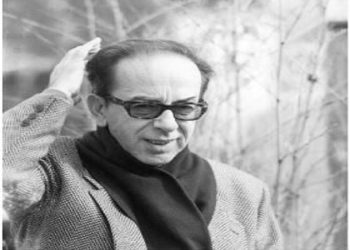

Unlike your brother, the well-known writer and translator, Dionis Bubani, you have not devoted much to artistic publications. However, you have written and published “Poku çamarrokun”, a book for children that remains loved by everyone who has read it. Why aren’t you more into publishing?

Literature has always slept inside me. Literature for me is love. But my work as an editor has not left me much space to write. However, I am happy that I realized a character like “Poku çamarroku”, which I think will remain in Albanian children’s literature. I think it is not important how much you publish, but what you leave behind. Even if you sculpt a character in the universe of literature, you have done the right thing.

You have led a very rich and eventful life. Do you have any mortgages?

(Smiles) I may have some small problems, but the important thing is that I feel complete and fulfilled with everything I accomplished in life, both with my family and friends and the contribution I made to society. To my children, I leave my good name and the memories that live on in everyone I have known. Memorie.al