From Sofika Prifti Cara

Part Eight

To Forgive…!

– The Old Kavaja Clan – CARA

Memorie.al /publishes excerpts from the book ‘Të falësh’ (To Forgive), authored by Mrs. Sofika Prifti (Cara), a publication of the Institute for the Study of Crimes and Consequences of Communism in Tirana, in which the author has meticulously and professionally described the history of one of the most prominent clans, not only in the city of Kavaja but also beyond, the Cara clan. From this clan emerged not only distinguished patriots and national figures who contributed to the national cause and the freedom of Albania, but also notable intellectuals, graduates of Western universities, who later returned home, contributing to various fields of science and life. However, even though the descendants of the Cara clan dedicated their lives to the national cause, after the communists came to power at the end of 1944, they would be persecuted, imprisoned, and interned, and the fierce class struggle would pursue them until 1990, when the collapse of the communist regime began.

Continued from the previous issue

THE COMPARISON

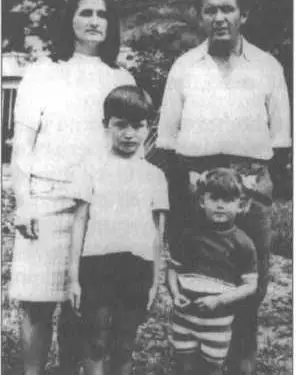

This is what my life was like! Apart from my state job, I had to work at home, too: embroidering dowries for the daughters of wealthy families, knitting sweaters, socks, suits with camel wool for women – I worked whatever they ordered, just to earn money. Like the farmer, I too had to pay off the debt, feed my mother-in-law, who had fed my husband, and “deposit” in the bank, meaning feed my children so they would feed us when we were old; I had to feed the family, meaning support my husband in prison, and feed myself.

Even though I did not amass wealth, just like the farmer, through work and intellect, I managed to keep my family united, with the pride and patience that God gave me! Now that I am writing these lines, I live with my husband, son, daughter-in-law, and my two grandsons, with my married daughter and my two granddaughters. In the second episode, the one with the grasshopper, the farmer won a job, while the great God gave me a strong mind, patience, and the strength to support my family, to hold my head high, with honesty and a “white face,” as the saying goes.

I did not give up, I was not defeated, but I raised my two children. Like the gardener’s tree, I also stayed in my first fate, in my own shade, and enjoyed the fruit of honesty. In life, truly, after every pain you experience, you will eventually see something good, so good things come after bad things. This is what an honest person dreams of. I worked very hard back then, but my life was hell. Fier is truly the city of my birth, while Kavaja is the city of the cradle that rocked Bardhi.

How different these two cities were! Fier had many very good people, but it also had some, about whom I don’t know what to say! Didn’t their conscience bother them, for the harm they did to others?! Because an egg, unless broken, cannot be fried. Many of these people today go to churches and mosques and pray, or ask God to forgive their sins. Even if man and God forgive them, do they themselves feel what they have done? Does their conscience bother them, even a little?! Do they truly repent, do you think?!

Because the great God is truly merciful and forgives those who repent. For me, such people are like leaves that have been shattered by hail, they have yellowed, and if the slightest wind blows, it casts them to the ground. In truth, the locals of Fier are cultured, gentle, welcoming, loving, and tolerant people, who know how to forgive, as the people say. It is known by all that there is no forest without wild animals.

Kavaja, however, is somewhat different; people here are very close to each other, they are hospitable, respectable, and above all, they are religious, gentle, and kind, like the climate they enjoy – in short, a place of doves. This city welcomed many people who were declassed by that regime, opened its doors to them. The locals did not look at the “declassed” with a strange eye, but offered them their generosity, as if they had known them for years. I did not see this beautiful thing in the city of Fier. Bardhi’s entire clan is from Kavaja.

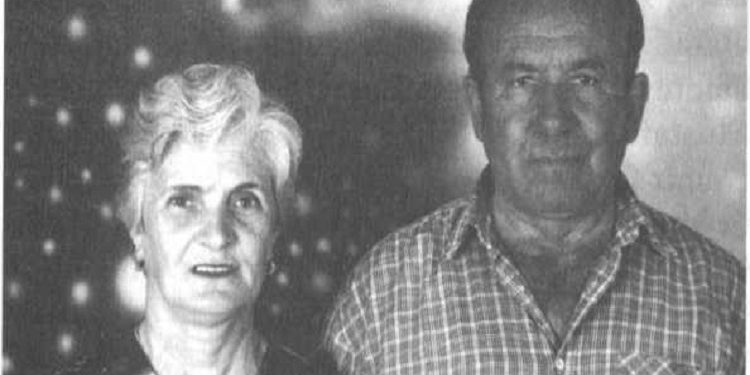

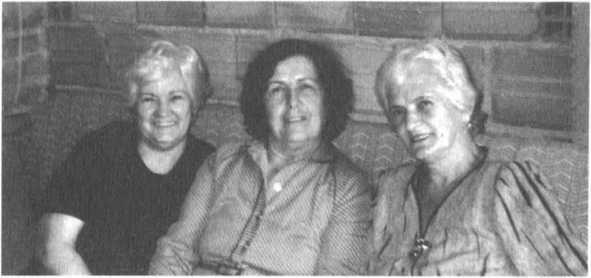

From the first meeting with them in 1961, they became very close to me, and, naturally, the respect is mutual. As soon as I got my usual leave, my mother-in-law’s sister, Bija, would come and take me and the children. That house became like my parents’ house to me. My aunt’s son, Baki Dervishi, became like my brother, his wife, Meleqja (whose name meant angel), truly was an angel – she was more than a sister to me! Together we cried over life’s many woes. How did that woman never get annoyed with me or my children!

She was a special person, an extraordinary woman! They had four children: Fiqretja, Sanija, Mirsija, and Muharremi. Four stars, each better than the last, and very loving. Both of them, husband and wife had very short lives. Unfortunately, they died very young. I was warmly welcomed by my aunt’s daughter, Nazime (Zimja), married in Durrës to Isuf Xhymerti. A good man, welcoming, worthy of a toast, as the saying goes.

Uncle Dyli, my mother-in-law’s brother, was a true gentleman. His son, Allaman Idrizi, and his wife, Hana, would not let you get bored when they spoke. My cousin, Dilja, and her husband, Ibrahim Gjuzi, not only welcomed me themselves, but his father, Hamit Gjuzi, would personally take me into his house. They respected me very, very much. All the people of Bardhi’s clan received me with great generosity; they wanted to lighten the pain I carried, however little.

Aunt Mynyrja would send her son and daughter-in-law, Fehmiu and Merjeme, to my aunt’s house to pick me up. I can never forget Mëmë Dija, the mother of Uncle Hajrije’s wife, who, every time she learned I had come to my aunt’s house, would send her daughter, Vaku, to fetch me. Her brother, Rremë Mullaliu, and his wife, Kimete, also welcomed me warmly to distract me from my sorrow, because I had been separated from my own people while still alive.

I even had nice holidays in Kavaja, but my heart was bleeding from despair. The days I spent in Kavaja were like medicine to heal the wounds that had opened in my heart. They wanted to relieve the stress, which had extended its tentacles like an octopus, or like the roots of Bermuda grass, which, no matter how much you cut it above ground, continues to spread below.

But what good was it? Those days were numbered, they were too few for me, because as soon as I started work, the calls (barks) for the “class struggle,” for our separation – husband and wife – would resume! And how many such separations were happening every day?! Poor people, forced, imposed, were separating, but not willingly. Waiting silently for their ruin, and the silence was like drinking rat poison to kill oneself! Finally, I was fired from my job!

DISMISSAL FROM WORK

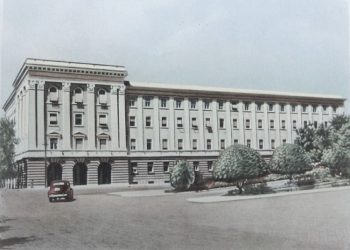

As soon as I was fired, I came home completely distraught, and my tears wouldn’t stop. My brother-in-law, to calm me down, said: “Why are you upset, Sofi? Tomorrow we will go to Tirana together, and then, let it be as it is written!” The next morning, together with my brother-in-law and my two children, we went to Tirana, to the High Court. It was the day for receiving citizens! Stavri Stratobërdha, a true gentleman with a big heart, very measured in his words, was receiving people.

He was a very good man to our entire class. After I told him in detail where I came from and about my husband, who had been sentenced to 15 years, I told him I had been fired and had nothing to live on. I requested that it would be better if they imprisoned us too, because there we would at least eat a spoonful of soup to keep our souls alive!

“If their father committed a crime,” I told him, “he was sentenced to 15 years, but what crime have the children committed?”

He, with rare serenity, looked at me for a moment, then gave me a piece of advice I will never forget, even though many years have passed since December ’67.

“Do you see this armchair where I am sitting? I am neither the first nor the last; who knows how many others will sit here. Haven’t you heard that wise folk saying: A good captain is known in a storm and tempest; when the sea has big waves, he never abandons the ship, but fights with his life until he brings it to shore, unvanquished by difficulties!”

The conversation changed topic because his secretary, who was a little late, entered. The children burst into tears, and he instructed the secretary to get a train ticket for me and something for the children, but I refused. Then, Mr. Stavri, with a look of despair, called the head of the human resources department where I worked, Marika Leka, and instructed her not only to rehire me but to let me work within the collection/assembly department. I thanked him wholeheartedly for everything he did for me and went outside with the children.

My brother-in-law was waiting for me outside, and we returned home, somewhat calmed. The elders have words of gold: “Life is like a rolling ball, crossing mountains, fields, hills, oceans, seas, thorns, and flower gardens, and the patient one truly suffers a lot, but later emerges victorious, no matter how many troubles and obstacles there are.” The head of the human resources department finally remembered to notify me to restart work after three weeks. As soon as she saw me at the door, she greeted me with shouts, as if I were a small child and had committed a fault. She forgot that I was a mother with children.

“Why did you go to Tirana?” she snapped at me angrily. “What should I do about Comrade Stavri? But you don’t deserve to work in our enterprise, because if you loved our party, you would have divorced your husband long ago – you were called upon many times! Tomorrow you will start working with the hides department; take the letter and go there. Know that you are within the enterprise! If you like the job, stay; if you don’t, go back to Tirana! It’s not our fault; this is the job we have!”

The next day I went and started working with the hides. I was the only woman among eight men, wonderful people: Andoni, Themiu, Hamiti, Mynyri, Sazani, Arti, Shabani, and Agroni, who became like eight of the best brothers to me. Later, two of them retired: Andoni and Hamiti. The work was six months during the day, six months at night, and an hour away from the village of Sheq i Madh. I had learned the conditions beforehand, but I accepted out of necessity.

When I first went there, it was winter. The work was during the day for 6 months, but it was a real hell. The heavy smell of the hides stank, as if the animals had died long ago, and it pierced my nose. Until I got used to the environment, my stomach could barely accept any food to eat. The thick hides of cows, calves, and pigs were salted, while the thin ones, those of sheep and goats, were dried in the shade. The warehouse keeper there was Sazani. The day I started work, he told me:

“This job, sister, is not only hard for you, being a woman, but also for us men, because you will load and unload the trucks with bales of salted hides, which are very heavy. I’d better tell you from the start so you know. You try it once; if you can’t do it, leave yourself… That’s the order I have…”!

In fact, the bales of hides weighed from 30 to 50 kg. They were too heavy for me, as a woman! I worked with effort, out of compulsion, which later led to me having stomach surgery. But where was I to go?! There was no other job for me! I was obliged! We kept our feet in rubber boots, winter and summer, which were given to us twice a year, and sometimes only once when there was a shortage.

They would tear early, and to avoid working barefoot, we sewed them with a needle (!!) The brine from the salt would seep through the needle holes, no matter how small, and our feet would turn white, wrinkled, as if they had been pickled or kept in lye with hot ash!

The sheep and goat hides were dried, hung with reeds. I was tormented until I got used to it, although my hands were often cut as if by a knife from the reeds. Flies were present; few in winter, but in summer, they covered our faces. Those cursed things multiplied and laid tiny maggots, so the hides would become full of them. The building was two and three stories high; the floorboards were placed with spaces between them, so the air could circulate to dry them as quickly as possible.

How terrifying it was in the summer! The hides filled with tiny maggots, and as the hides began to dry, the maggots would slowly fall from above to the first floor where we worked. Those cursed maggots would fall on our necks, on our heads, get into our bodies, causing us a lot of itching and discomfort. Our bodies would bleed, and our clothes would stick to us from scratching! During the summer months, work would start at 11 at night for 6 months, and end at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 AM, depending on the volume of livestock at the slaughterhouse!

Keep in mind, I was very young. The work was almost an hour away, the road had tall, large poplars on both sides, creating deep darkness. Because there were no lights, the village dogs were let loose on both sides of the road, as there were a few houses nearby. I was afraid to go alone; my male colleagues were on bicycles. I cried from frustration when they announced that work would start at night. The seven men discussed it together and told me:

“You, Sofi, don’t worry; we won’t leave your children without bread! Now you are our sister; we will never leave you halfway!”

They made a weekly schedule, taking turns coming to pick me up at home, instructing me to be outside the door at ten o’clock. Even Themiu, who was older and retired after a while, did not skip his week while he was with us. Shaban Gashi’s house was next to the workplace, but he would make the entire trip to pick me up at home and was never annoyed! They pressured him and told him at the enterprise: “What do you care that you go and pick up that woman! Just stay put!” But he did not listen to them. Because Shaban Gashi had a big heart; when we loaded the trucks, he would let me work in his place, stacking the bales.

We took the hides from the slaughterhouse on handcarts, one by one, to process them; the road was rocky, and I could barely push the cart. The wheel would often get stuck on a rock, and the hides would fall down because they were heavy, but Shaban and the others would come and help me. He had a big heart, he felt sorry for me. “Don’t give up!” he would say in a low voice, because he had heard that they brought me there to get discouraged and leave on my own.

The supervisor, Myrto Braka, would occasionally tell Shaban, with a tone of dissatisfaction: “I told you, but you won’t listen! Leave her, don’t help that woman!” Yet, in front of my eyes, when he came to the hides, he would tell them: “Help her a little, it’s a sin!” He was from the village of Mbret in Fier. How many reprimands did that man receive because of me! Truly, it was a very hard job! The warehouse keeper, Sazani, would tell his colleagues:

“They told me not to help Sofika, so I’m telling you what they told me, so you don’t say I didn’t tell you!”

Shaban would jump in first and tell his friends about me: “It’s a sin to leave her alone, she is a good person, it is her children’s bread. Don’t you see how hard she tries, she works honestly; for a woman, she never says ‘I’m tired,’ she looks at us with tearful eyes. What do you say, guys, should we help her or let her get upset and leave?” I will never forget Shaban Gashi! God bless and help him and his family! Apart from Mynyri, who was 5-6 years older, the others were young.

They called me over, lit a cigarette, and told me: “You continue the work as you have been doing; you will work here with us. Let the dogs bark, the caravan moves on!” and they began to help me more and encourage me. For these good people, I cannot find enough words of gratitude; they were wonderful brothers to me. These brothers will remain unforgettable in my mind and heart. I pray to God to reward them with all His goodness! I thank them deeply from the bottom of my heart.

After working with them for many years, I got used to the hides environment, and the directorate failed to make me quit the job, although they still didn’t leave me alone. One day, people from the directorate came and removed me from there. They sent me to the pig fattening farm; the reason was that I was earning too much money!! It was a piece-rate job, with extended hours, and the salary was high there, too; they needed a woman. They brought many women there, but none stayed, because the work was hard, the smell was terrible, unbearable; but me, whether I liked it or not, they brought me there again.

Loneliness is like viper’s venom, slowly poisoning you. My dream at that time was to raise my children. Ohh…! Would I be able to climb the stairs of life, which for me were like the threads of a spider’s web and as high as the sky? I thought this was a dream, not a defeat. “Oh, Saint Mary! You are a mother yourself, I would sacrifice myself for you, never leave me alone, make me as vast as an ocean, and whoever wrongs me, you take revenge for me!” Memorie.al