From Sofika Prifti Cara

Part thirteen

To Forgive…!

– The Old Kavajë Clan – CARA

Memorie.al publishes several parts from the book ‘To Forgive’ , authored by Mrs. Sofika Prifti (Cara), published by the Institute for the Study of Crimes and Consequences of Communism in Tirana, in which the author has described in detail and with professional competence, the history of one of the most renowned clans, not only in the city of Kavajë but also beyond – the Cara clan, from which emerged not only distinguished patriots who contributed to the national cause and the freedom of Albania, but also famous intellectuals, graduated in the West, who later returned to the homeland, contributing to various fields of science and life. However, even though the descendants of the Cara clan dedicated their lives to the national cause, after the communists came to power at the end of 1944, they would be persecuted, imprisoned, and interned, and the fierce class struggle would follow them until 1990, when the collapse of the communist regime began.

Continued from the previous issue

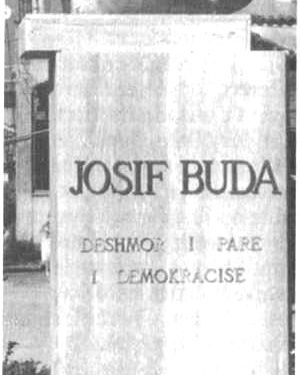

THE MURDER OF JOSIF BUDO, THE FIRST MARTYR OF DEMOCRACY

I had just returned from work, and I didn’t find my son at home. In the “Çobanëve” (Shepherds’) neighborhood, high-pitched voices were heard, and the noise grew louder and louder. My son’s delay made me anxious, so I went out to look for him. I came down from the building and met Sifi. We are neighbors, and he asked me:

“Where are you going, Aunt Sofika?”

“I just got back from work,” I replied, worried. “I didn’t find Beni at home, and I’m going out to look for him.”

“You go back; I’ll find him and bring him home,” he told me.

“No! No! You’ll be late, and I’ll worry; I’d better go myself. I hear a lot of noise at the ‘Çobanëve’ neighborhood,” I said. “Where are you going?” I asked him.

“To my maternal uncles’, to watch the football,” he said. The World Football Championship was being played in Italy those days. Televisions were scarce, and many football enthusiasts would go to watch the matches at their relatives’ homes. Sifi had taken a large piece of bread with half a tomato and some cheese. He was washed and well-dressed, looking like a groom! Walking along the small alley that led to the main road, we met a neighbor named Nini. As soon as she saw Josif, she told him:

“Oh, Sifi, you look exactly like a groom!” He laughed like a child. “Don’t eat bread on the road, or the matchmakers will fight – that’s what the old folks say,” the neighbor joked. The three of us were laughing. When we came out onto the main road, we saw many people at the “Çobanëve” Neighborhood. The place was buzzing like a beehive. We hurried and went there (we are close). The sampistët (police/security forces) were behaving like wild beasts with the neighborhood residents. Sifi’s brother, Koli, was wrestling with one of the masked Special Forces. Sifi still had a little bread in his hand, but when he saw his brother, he immediately dropped it in a corner and lunged toward the brutal sampist who was hitting and kicking his brother.

After exchanging a few words, the situation quickly escalated, and taking advantage of the moment, the sampist pulled out his weapon and shot Sifi. The innocent boy fell, bleeding, at the feet of the screaming crowd. Many other angry people gathered. The terrified sampistët immediately picked him up and, like a rifle bullet, took him to the hospital to give him first aid. But the boy, his mother’s brave son, Josif Budo, had closed his eyes forever. The one who killed him hid in the darkness of the night, on the terrace of the Maternity Hospital. Sifi’s brother, Koli, who had been slightly wounded, was quickly brought home and put into a room, heedless of his piercing screams.

The residents of the “Çobanëve” Neighborhood, with uncontrollable rage, rushed upon the armed sampistët until they were forced to flee toward the main square. Along the way, they hit anyone who crossed their path with rubber batons. They struck them as if they were enemies, as if those people were not their Albanian brothers! The youth of Kavajë poured into the hospital. Some boys took a white sheet from the maternity ward, wrapped Josif’s lifeless body, and marched toward the city center, stopping there for a few minutes. Then they lifted him from there and started silently parading him through the city. The silence of those young people held a great significance. That silence seemed to tell the citizens, the parents of Kavajë: wake up, come with us, because the communist beast craves blood because it is in its final hours!

Sifi’s body was brought home late; he was placed on the cement well curb to wash the blood that had trickled down in red stripes, just like those placed by mayors on holidays. Great sorrow began in the house. You didn’t know whom to comfort first among the family: Mother Sila, who was utterly lost, Father Kiço, who was pulling out his hair, the brothers, the sisters, Uncle Koçi, who was punching his head, Aunt Liri, with her son and daughters, because they had grown up together in one house and at one table! I myself was an eyewitness when Josif Budo was killed and his brother, Koli, was wounded.

In the grief for Sifi, poor Koli was completely forgotten; his head swelled more and more because the bullet had remained inside. His pain increased. They called a doctor, but no one came out of fear. His screams were unbearable. Around 2-3 AM, an emergency doctor and a nurse arrived and removed the embedded bullet. I will never forget those dramatic moments, the loud, chilling screams when it was removed. From what happened in Kavajë, the serpent in power sent many military forces to this city for revenge. Thus, it showed its brutal face, as if it wanted to say: “I am still strong, and I will not surrender!” As neighbors, we stayed that night and watched over the body, according to custom.

The next day, the order was given in all enterprises: “No one is to participate in Josif’s funeral!” But they were gravely mistaken. Josif Budo’s funeral was magnificent. People came not only from the city but also from the villages to pay their last respects and bid farewell to the hero of democracy. Josif’s coffin was taken to the church, which was opened for the first time after the prohibition of religion. The mass was held by the municipal designer, Petraq Isaku, a former cleric who had been a classmate of Pope Wojtyła (Pope John Paul II). After its closure in 1967, the church had been turned into a cultural palace.

That day it was reopened for the first time, and from that day on, it returned to its original purpose. The coffin was covered with a beautiful cloth and bouquets of flowers, and his friends carried him on their shoulders to his final resting place. All of Kavajë was in mourning. Even the birds stopped flying and accompanied Josif, casting shadows from above on that hot July day. On the balconies and at the gates, the mothers and sisters of Kavajë wept from afar for their son and brother. The procession, before taking the road to the cemetery, marched toward the “Sharrë” neighborhood.

Not only had the Budo family lost their loved one, but all of Kavajë had lost its son. Fate determined that Josif Budo would be the “sacrifice” at the foundations of the fortress of democracy. After Josif’s funeral, the revolts escalated in the following days without interruption. People took to the streets and demanded, with the voice of protest, the departure of Ramiz Alia and his puppets from power. And so it happened. (With the coming of democracy to power, Prof. Dr. Sali Berisha decorated the martyr from Kavajë, Josif Buda, with the title “First Martyr of Democracy.” The Municipal Council declared Josif Buda “Honorary Citizen of Kavajë for the national cause.” Today, Josif Budo’s bust is placed in the large public garden in the center of the city. Among many flowers, that boy looks at us from the bust and smiles. He gives us faith and hope).

KAVAJË WAS FIRST

It was Kavajë that history assigned the mission to be the first to rebel and confront the dictatorial, Enverist communist system. In every period before, the residents of this city, in various ways, had expressed their coldness and distrust towards communism; they acted against that government. I recall here the citizen Xhavit Arkaxhiu, who, in the presence of the enterprise director, removed the photograph of Enver Hoxha from the wall and stepped on it. (They took that honest man as mentally ill!) Similarly, the workers of the Carpet Enterprise met Ramiz Alia with protests because they were mistreated at work.

The workers of the Pottery Factory went before the Party Committee and raised their voices in revolt over low wages and difficult working conditions. At the Nail and Bolt Factory, the workers rose up en masse against the representative of the Political Bureau because they received little money and little milk was sent to the shops, even though Kavajë produced it and Durrës was supplied. Kavajë, with all these signs, was the first spark, which the students later ignited more strongly with their great demonstrations, to break once and for all the heavy chains of such a cruel system, a system that isolated the country from the world and separated people from each other. Later in Shkodër, 4 young people were killed in the middle of the city on April 2, 1991.

The year 1990-1991 was the final limit of patience, unemployment, small wages, food on a list, and the complete closure of private businesses. It was precisely these reasons that made Kavajë rise up. But the other cities did not leave Kavajë alone, because they had the same troubles. Thus, united like an iron fist, the Albanians struck that hated system on the head. The great rally that took place in Tirana by the students will remain unforgettable, when the boys of Kavajë headed to Tirana by train and with chance vehicles. The police had blocked the road from Lapraka, where the people from Kavajë were supposed to pass. They had set up an ambush with sampistët on the road, but this did not frighten the boys of Kavajë, who bravely broke through the blockade and arrived at the square where the rally was to take place, circling the large square three times demonstratively.

All those present at the rally welcomed the democratic people of Kavajë with enthusiastic cheers, shouting “Bravo Kavajë!” “Long live Kavajë!” “Kavajë was first!” etc. When the rally ended, the people of Kavajë welcomed the boys at the entrance of the city and accompanied them to the square, cheering. In those touching moments, Kadri Cara (“Tata”) leaned out of a five-story window with his hand raised, like Hitler, shouting: “Enver-Hitler!” “Freedom-Democracy!” while the family members inside held him by the legs so he wouldn’t fall out the window. When Kavajë first started the anti-communist demonstrations, Ramiz Alia sent the Special Forces and tanks again to crush this rebellious, democratic city. But when all of Albania then exploded, he became frightened and removed the tanks and Special Forces.

Kavajë fell silent, but the tanks had left the tracks of their chains, not only on the highway but also in the memory of the people. That system, with the force of dictatorship, with pressure and fear, made people thieves, spies, sycophants, and liars, to keep them more easily under the yoke, defeated, to lose their dignity and morality. It wanted to make people wolves, to eat each other.

As a family, we never reconciled with these ominous goals. We were at the forefront of every demonstration because the place where we stood and our hearts told us: “Get up!” “Get up!” “Forward!” “Forward!” It was an internal, silent call that would serve for the future of our children, our grandchildren, so that they would no longer fear or be poor as we were in our lives, where we never smiled once, so that they would not know tears as we did, so much so that we still bear the marks of tears on our cheeks.

Ahhhh, if I were a writer, I would write whole novels, expanding these fragments I have written in the form of a narrative! I would write in detail about the life of the village in the past, about the roads, the meetings in prisons, about Burrel, Spaç, Skrovotinë, Ballsh, the internments, etc., the trials we went through in that dictatorial regime. I would describe the sufferings of my 53 years of marriage day by day, month by month, and year by year, how one by one we entered the “mouth of the shark,” it bit us, and the pains were very great, but we escaped being physically eaten. All those people who have personally experienced the electric current of that system and today have not benefited anything are people with big, strong, and righteous hearts, they are judgmental, who know how to forgive, because life and spiritual faith made them so. I do not want to write here about those “politically persecuted” who ate and drank as much as they wanted who held positions and educated their children here and abroad.

Their suffering and wounds, which Enver opened, are healed with an ointment, and today those same people are in power and have good jobs. In fact, some wild medlars entered the family of the sweet pear and graduated from university, at a time when background analysis was done for 7 generations, and today they are privileged. How did they get into university? They know themselves! May God judge them for the opposite of their work, because they continue to be first everywhere. That system counted teeth and molars for our social stratum. It wanted to take even what you didn’t have! Here is one example, among many others, from that system: truly, Kavajë was not like the other cities, because the people here are very different; they are softer, more tolerant, warmer, and more hospitable; I’m not saying there aren’t crooked trees here too, who have harmed honest families.

Remember Vlash Dhimitër Dimroçi, who was an honest man from Kavajë, minding his own business, working and earning his money with the sweat of his brow. He was a respected man and left these virtues to his children as well. But the communist system arrested this man, demanding the wealth he had earned with sweat. With Vlash Dimroçi, the communist executioners used the most inhumane tortures. To steal his gold, they removed his fingernails, dressed him in stockings, and lifted him up by his bloody fingers! Then they tied him with a rope and drowned him in a well! This was not enough; they also gave him a bullet to the back of the head. Vlash’s wife, Ksanthipi, was forcibly taken from her home, held for questioning, beaten, tortured, and then her head was shaved completely, like a man’s, and when they brought her home, she had completely lost her voice from the torture and could no longer speak! This family went through a great shock! One of the grandchildren (Vlash’s son??) took the grandfather’s name, Miti (Dhimitër). Since he was small, he was passionate about football and became one of the best players of “Besa,” but he was never properly appreciated while he was alive. Memorie.al

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)