By Agim Xh. Dëshnica

Part Two

Memorie.al / At a time when the dictatorship was rolling headlong into the abyss, several minor critics with scientific degrees attempted to go even further. In the book History of Albania, Volume II, 1984, the alienation of history crossed every limit, with distortions of facts such as these: “The representatives of the reformist current linked to the Sultan’s regime aimed to limit the national movement only to a few cultural and economic demands. The expression of the ideas and program of this current was Konica’s magazine Albania!” But who were these “representatives”? In the magazine Albania, Konica gathered around himself talented poets and writers such as Luigj Gurakuqi, Gjergj Fishta, Çajupi, Fan S. Noli, Asdreni, and Filip Shiroka – known in history as patriots of the fatherland’s freedom and independence.

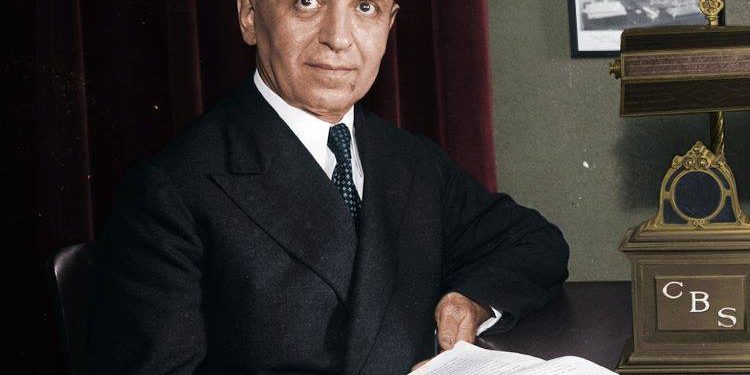

Meanwhile, in the book History of Albanian Literature, one finds these lines filled with untruths, slanders, and insults: “Faik Konica (1875-1942). Son of an old family of beys, primarily a publicist, he began his literary activity with the publication of the magazine Albania (Brussels 1897) and directed for some time the newspaper Dielli of the Albanian emigration in the USA, where he spent most of his life.”

Genuine scholars of history unite in one thought: Faik Konica, this genius of Albanism, is the most powerful link between the Albanian National Renaissance and the great historical developments and the triumph of National Independence, a great master of the Albanian language, and a personality of culture and literature. Only after the 1992 triumph of the democrats in Albania was Faik Konica honored by them with the high title, “Honor of the Nation.” According to an old wish expressed to Noli, he now rests in his native land which he loved so dearly, in the hills of Tirana near Sami, Abdyl, and Naim Frashëri.

Continued from the previous issue

FROM KONICA’S PROSE: ‘THE RELIGION OF THE FLAG’

“The red flag with the black double-headed eagle, the Flag of Scanderbeg, Our Flag, is among the most beautiful in the world. That Flag waved in 20 renowned wars, wars to defend -not to suppress – what is right. It is the Flag of honor. It is the Flag of Liberty. But even more, it is: the symbol, the visible sign of our Nationality. With this Flag mentioned by historians and sung by poets, no one can deny our Nationality.

Sons of Albania, the hope of the Fatherland, neither you whose blood is not yet chilled by suffering, nor your brains dried by self-interest – why does your heart not strike when you see the Flag of your race?

You must not only honor it, you must love it – love it with depth and fire. But to love it, you must understand it well… It was a mistake of those who said that the youth must learn from the elders. NO! History shows us that the elders have always learned from the youth. The Albanian Youth taught the Albanian Nation the Religion of the Flag!” (Published in ‘Trumbeta e Krujës’, April 15, 1911)

LONGING FOR THE HOMELAND

“When a man goes, free and alone, far from the fatherland, the new sights, the change of customs, the sweetness of travel, and a thousand things observed among foreign peoples – all these cheer the heart and make you, if not forget Albania, at least not have it so frequently on your mind. Later, as the eyes are first satiated with changes, the joy fades little by little. You do not know what you lack; you do not know what you need. A shadow of sadness covers your face; and, at first occasionally, then more densely, and finally often – almost always and everywhere – the memory of parents, of friends and companions, the memory of the soil where we were born and raised… the memory of the nation… and more so the memory and the desire and the thirst for our language, truly tighten and crush the heart.

Ah, the longing for Albania, the longing for the beloved Fatherland, a sacred longing and a sacred love – what Albanian has not felt it in a foreign land! You must be outside Albania, and be far away, to understand what force and what sweet beauty this word has for the ears: Albania!”

SOME MEMORIES OF FATHER GJEÇOVI

“I had known Father Gjeçovi through letters some years before the Balkan War. In 1913, I went to Shkodër and there, in the Franciscan Convent, one day we met eye to eye and with living words… Medium in height, somewhat thin, with a pair of black eyes where intelligence but also kindness shone, Father Gjeçovi immediately won trust and love…

…At that time, Father Gjeçovi was a ‘parish priest’… and lived in Gomsiqe, the first village of Mirdita… Father Fishta, with whom I met every day in Shkodër, asked me: ‘Shall we go as guests to Father Gjeçovi one day this week?’… The parish – a stone building, bright and clean, half-empty of furniture but filled and beautified by the great heart and the smile of the master of the house… Here lived Father Gjeçovi. Here he spent his life, amidst prayer and studies, one of the most elevated men Albania has ever had: a humble height… a height of soul and mind unknown to the man himself, who, a true son of the Poor Man of Assisi, in the purity and poverty of his heart, considered himself small.

He gave the children the foundations of training, distributed wise words and consolation to people in need. The time he had left, Father Gjeçovi dedicated to study. He was then dealing with the ancient institutes of Albania, one of which reaches our days – the Code of Lekë Dukagjini (Kanuni). No one could approach Father Gjeçovi in the knowledge of this Code.”

BY THE LAKE (Anës Liqenit)

“Night is approaching. The light of day fades gradually; and, over the roof tiles of the houses, over the boards of the streets, over the leaves of the trees… a violet color – a pigeon-breast color, as they say in some of our mountains – stretches and envelops them… Stars pierce the sky, dripping light. Night has come. And when night comes, I like to go and sit by the lake.

It is not like Lake Ohrid, with waters clear as a brook; nor like Lake Janina, which shines like a field paved with mirrors… It is a lake no larger than a garden, in the middle of a cultivated forest, a lake foul and beautiful – foul because its water reeks, beautiful because the trees surrounding it hang their branches to its very surface, and upon its surface, the moon shines and plays.” (From ‘Albania’ – Brussels)

THE LEVANTINES

“I heard these strange words one day in Tirana: ‘Puisque l’occasion se présente…’ Surprised to learn that there were Negroes in Albania, I turned my head to see the two Africans. But my surprise increased, discovering that the speakers were white… dressed better than they should be…

…From all their movements, it was easily understood that they were afraid of being mistaken for peasants, for mountain people, unpolished and untrained in the details of civility. Who were these people? …I understood I was dealing with a breed of people that I, along with some like-minded friends, have called for twenty years ‘Levantines.’ They constitute a separate class among Albanians… The fundamental thought among Levantines (if dolls can be said to have thoughts) is that everything old in Albania appears to them either base or ridiculous. They are convinced that Albanian is a weak language, incapable of discussing important matters or expressing refined feelings.

In this point, they resemble a semi-savage man before whom you might lay a priceless old violin—a Stradivarius or an Amati; and since he knows how to draw from the rare violin only a sound like a saw hitting a nail, the unpolished soul believes and says the violin has nothing to do with music… The ‘etiquette’ of a highlander who has inherited the customs of his ancestors has a beauty, a detail, and a clear scent which have pleased all the artists, writers, and people of good houses in Western Europe.”

PROMETHEUS BOUND

“‘La vie est triste, hélas! et j’ai lu tous les livres!’ (‘Life is sad, alas! and I have read all the books!’) With this line begins one of the poems of the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé…

…I sat one night in my room… and from the shelf, I pulled a small, thin book… my eye caught this line: ‘He who has commanded for a short time is always harsh’ – a weak translation of a text strong as bronze. Who said this profound word? I glanced at the title and saw in Latin: Aeschyli Prometheus.

A book two thousand four hundred years old; but in thoughts so young, it seemed as if it were written yesterday… Aeschylus is the highest and deepest poet of classical antiquity… Among all his works, the deepest is Prometheus Bound… it is the eternal drama of the idealist who suffers for his thoughts…

…On every page, I discovered things that increased my wonder… Prometheus cries the terrible tragedy of his own life: ‘Look,’ he says, ‘look, a wretched god bound, and why does he suffer? From the great love he had for men.’ On the occasion of these words, we notice the affinity of Prometheus, cast in irons for the love he had for men, with the crucified Christ…

Aeschylus puts in the mouth of Prometheus a profound judgment on the character of tyrants: ‘Tyrants have a bad vice, that they do not trust their friends.’ …And the crowning of the work, words full of pride and noble force: ‘Time, as it advances, will give all the lessons.’ But unfortunately, lessons often come too late!”/Memorie.al