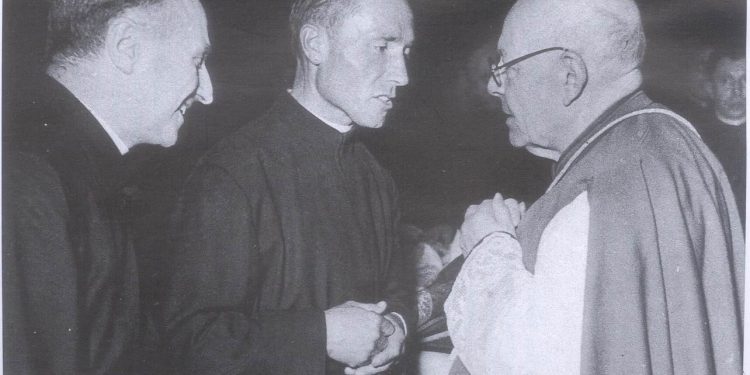

By Father Giacomo Gardini

Memorie.al / Father Giacomo Gardini, pious missionary and why at the age of 87, he returned to Albania to continue the work that was violently interrupted by the dictatorship of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Father Giacomo Gardini was born in Pordenone, Italy in 1905 and after entering the Jesuit society, where he was trained as a clergyman; in 1930 he came to Albania and spent several years teaching in the religious colleges of that time, mainly in the Shkodra District. In 1936, he was ordained a priest and continued to serve in the Albanian Catholic Church, until he was arrested in early 1945 by the communist regime that had just come to power. After being held for some time in the investigator’s cell, in one of the improvised prisons of the city of Shkodra, he appeared in court in the summer of 1945 and was sentenced to ten years of imprisonment, accused of being an “enemy of the people” and “agitation and propaganda against popular power”, from which he suffered 8 years in prison and 2 years of exile. After being released from prison, it becomes possible for him to return and repatriate to Italy. Spiritually, he was never separated from Albania despite all the suffering he suffered. In 1986, Father Giacomo Gardini published in Italy the book “10 years in prison in Albania”, in which he describes in detail his life in Albania, mainly from the period of arrest, investigation, trial and suffering in prisons, until he was repatriated to Italy in 1956. While after the reopening of the churches, Father Giacomo Gardini returned to Albania, to serve again as a priest and his religious mission continued until 1996, when he passed away. The part that we have selected here for publication is taken from his book, “Ten years in prison in Albania”!

NARRATIVES OF EVENTS FRAGMENTS FROM THE BOOK “TEN YEARS IN PRISON IN ALBANIA”

Arrest and process: In the old prison of Shkodra…!

After I received the “reward I deserved”, with the executive decision (August 28, 1945), I was transferred to the old prison of Shkodra, known as the Great Prison, which is located behind the Prefecture. It had been built in the time of the Turks, when Porta e Nalte ruled: a medium-sized building and terrible in terms of comfort: allaturka indeed! It was quadrangular with two floors: on one side you can find the directorate and the police force, on the other three sides, the prisons. There were two or three rooms for the sick and a few cells, generally placed below the stairs, especially for the most dangerous prisoners or subject to the strict regime.

Inside, a courtyard of 25 x 8 meters, in the center with a hand pump to draw water from the well. The apartments consisted of four large, shabby rooms with plank floors. Each one could occupy, lying on the ground, in four rows, 40 to 60 people. At night, especially at the time of the largest gathering, you look like a carpet of bodies and a tangle of crossed legs. Dense colonies of parasites lurked under that carpet.

From the small courtyard, on the lower floor, were the latrines, located in a street without windows, without water, with five or six allaturka “places”, that is, simple dungeons on the floor that led the filth directly into the ditch; therefore the stench was unbearable. On the sides of the yard, under the stairs to the upper floor, two dungeons served as bathrooms and also punished the disobedient ones, you beat them with a stick or you threw buckets of cold water at them, or you kept them awake all night with the head sits under the stairs with the legs submerged in water up to the knee, a punishment which I also had the opportunity to experience.

The only place for morning cleanliness was for the entire water pump between the courtyards. Almost every day we were made to walk around for an hour inside the small courtyard under the supervision of armed guards. No radio, no information. Controls were very strict. Any violation of the regulations or a simple suspicion, caused, perhaps, by a sneaky spy, was rewarded with a beating of sticks, as much as every fiber of will was torn. Food consists of 700 grams of bread, mostly corn bread and tap water. These were the common elements of my whole life as prisoners. Some small improvements were made, as I will show later, but the basis remained the same.

As I pointed out before, the environment was completely filthy with parasites: bedbugs and fleas, but the most furious were the lice, so much so that no one managed to get rid of them even though they took care of cleanliness. The sides of the walls were completely covered with red stains. Fortunately, the Americans supplied all the allies – including the Albanians – with large quantities of DDT. In addition to the population, something remained for us “enemies of the people”.

One day of days in our rooms, everything, boards, clothes and naked, we passed and repassed through a fog of dust against insects. Then they ordered us not to touch anything for three days and three nights. It’s easy to imagine how we got through that breathtaking storm! Although we were in danger of poisoning in that environment full of people, we were still disinfected from the parasites and we all remained satisfied.

The Americans, then, along with DDT, sent supplies, very fine flour. Fate wanted that even the prisoners, for a little while, had some profit from that abundance. Some soft and white french fries would also arrive in the prison, so that they would be satisfied just by looking at them. Some of the prisoners, especially the mountaineers, who had never seen such bread, threw themselves into it and ate it greedily. But after a few days, one says to the other: “For five days now, I have had to go out on my own.” The other: “And I’m six now!” Word of faith passed from mouth to mouth, and a large number of prisoners found themselves in the same conditions. It could make a real mess.

The directorate, informed us, immediately took strict measures. The next day, a demijohn of thick oil arrived in the courtyard and started pouring it there. The measure of oil was a glass, which, as soon as it was drawn from one, was immediately filled for the other. The cure, certainly radical, does its job. At that moment there were more than 500 of us, while the needy were the ones I described. When he saw that white bread “was bad for us”, the prison administration ordered the usual ration of corn bread.

Field of concentration: In the construction of the Vlora prison

The population of the Tepelena camp could reach around 1,500 – 1,700 people, or even more. If you think that the internment operation had already started in 1945, at the time I’m talking about (1952-’53), the boys had already reached the age of 16-17, and therefore they were valuable for work. It happened that they were often called for urgent or necessary work.

After Easter 1952 – which, like now, was a big holiday for us – news arrived at the camp that he was about to leave for a work mission. Lists of persons physically able to work were prepared; those little things were gathered, greetings were made and even some tears were shed. About 170 of us left. The group stopped on the outskirts of Vlora, next to green hills full of olive trees. Our dwellings were wooden shacks, with bunk beds, even adobe with some taste.

All the entrances lead to a large square that is used as a yard and as a building material warehouse. We arranged ourselves as we wanted, as according to friendship, kinship, age, as being in the family. From the courtyard, the eye could wander over the open sea area from where Arta descends, until it embraced Vlora and its harbor as far as Kania; the island of Sazan was visible in the distance, you say that it was placed as a guard for the whole area. A clean and fresh air was blowing from the sea, a miracle!

The next day after our arrival was completely occupied with the organization of the work; division into groups with the respective responsibilities, limited freedom to go to the city, disciplinary norms inside the camp, possible punishments. Then the tools were shared. I was very happy when I saw that as director of works, there was an Italian, the engineer Ugo Monai – a Friulian from Tricesimo (Udine). The workers loved the engineer for his courtesy and kindness, while the superiors appreciated him for his ability. During our years he was, especially for us priests, a guardian angel.

The area that stretched in front of our camp looked like a completely drawn sheet: partly dug into the ground with a hole, partly leveled with pegs. It was the project of a more or less complicated building and the place where you are located was not clearly communicated to us. However, for us who – as they say in Albanian – “had tasted some soup” – it was not difficult to understand that a large prison building would be built there. I was already held as a half-master; therefore I was entrusted with a particularly important and delicate sector in that prison system: rooms for prisoners under trial or sentenced to death.

The preliminary form was that of a building of 10 x 8 x 35 meters with a single entrance, no side windows, but with skylights in cement on the ceilings, from which some light and air entered. The interior consisted of a narrow passageway running from one side to the other. Along the two sides of the corridor, there were cells of different sizes, some in more than strange shapes: maybe they were set up for…torture.

In that construction site, the man worked with good will; the food was not delicious, but good and sufficient. Even our guards had found out that the internees were not prisoners serving their sentence, even more so since free workers who received a regular salary had been hired near us. However, it had to be a long time before we were recognized with the right to pay, in addition to a plate of soup, some reward for our work.

We worked, who eroded, who filled the foundations, who laid the stones, who prepared the lime: from the ground it was not long before the shape of the entire building was visible and it rose almost a meter high. Meanwhile, in the olive groves that covered the hills, the olives had begun to ripen, which constantly excited the taste of the workers who worked without rest. As night fell, sneaky shadows left your barracks and slipped under the trees, returning full of “stolen fruit”…!

We ate olives, prepared in a thousand ways, until late autumn, with the consciousness that there was nothing wrong with us. Of course, they also gave me the traditional greeting: “Good luck!” and with the smile of a man who feels at ease when he shares the small meal with the priest!

As I said above, at that time, apart from daily food, they did not give us clothes, shoes, or money; and few were those who could get money from other sources. I then less than everyone. But one day I was called to the directorate because a check for five dollars had arrived from Italy. With money, in dollars, from Italy it shakes!

This was more than enough reason for suspicion. But the worst thing was that the check had come from the Vatican. “Ani – asked the director – money from the Vatican? Who sends them? And with what purpose”? I asked if I could scan the document, because that was the only way I would know who the sender was.

As for the reason, I said it was obvious, you showed my elegant outfit! That was the end of the conversation. I don’t know how much they gave me in Albanian currency; however, it wasn’t long before there was any doubt.

A year and a half later, always in matters of financial aid, another case happened to me that could have had much more serious consequences. The relative of one of the internees used to send me from Tirana one hundred ALL (which was worth a little more than one Italian lira), they said that it was the help of someone who did not want it and their name was revealed. I took this request for good, and in the conditions I was in, that help, no matter how small, didn’t hurt me; but I am disappointed that I did not thank the benefactor after seeing the announcement.

One day I was called to the police headquarters and they actually took me in a serious report. They started by asking me about things that had happened and tried to find out who my friends were when I lived in Shkodër. Narrowed and bored, I thought of my Jesuit brothers or friends, who I knew were far away and out of danger. Among others, I also mentioned the name of Father Pietro Palladini, deported from Albania with other Italians in 1946.

We were close friends and he was then in Italy. “And Father Palladini – the officer immediately asked – does he always remember you, does he help you directly or through other people”? I answered that I had no letter or help directly from him. – “And from others?” – He insisted. I then told him about the unexpected help that came to me from Tirana, from an unknown person. In order to remove suspicion, I also pointed out the small amount and that I rarely received it. “That’s enough”, concluded the officer, and let me go.

Later, when I returned to Italy, I found out from Father Pietro Palladini, that in fact he had sent the uninvited to Tirana from time to time, colors that were very much in demand at that time in Albania, so that with the profit from the sale, helped me and any other needy Albanian Jesuit. But the man in whom Father Palladini had faith benefited more for his own pocket. The police discovered the game and arrested him. During the minutes, my name also appeared. Because of this, I was called to the police station, but all my responsibilities were removed, I didn’t have any trouble.

“…we tightened them with clay bricks”

The work in Vlora had gone ahead all summer and the people in charge were satisfied; but autumn pushed on, the weather was already harsh, especially at night, the rails started to paralyze the construction site. We celebrated Christmas by collecting together some small items that we had bought, someone had gone all the way to Arta, he had found quite a good vein. After such a long time of “fasting”, the celebration created an extraordinary liveliness in the camp and even made us sing simple songs of the mountains, which were then known in the city. It was Christmas, and for a few hours we forgot our situation.

Except it was clear that it wasn’t going to go on like this all winter. And suddenly, about halfway down the hill, the order came to leave. The same job of loading our belongings onto the vehicles and onto them, dividing us into groups; the same departure at midnight with the biting cold of half of the city and the arrival in Tirana, when it was early morning. They dragged us through the dark courtyards of a brick kiln, and ushered us into the large, completely empty rooms, where we waited for the dawn. When the doors finally opened, everyone ran away with their needs somewhere…! Then they gave us the same cup of warm tea and after that we started to clean and renovate the new apartments.

The factory presented the best that could be prepared at that time. We were accompanied by the managers, we visited the different departments. They showed us all the stages of the work: the soil was collected, sifted, compacted, and turned into the desired shapes, baked into the bark, then into the baking ovens, from which the finished material came out. At that time and in that place, each one of these stages required working without interruptions and surprises. In the early days we worked alongside the workers who had been there for a long time; but, after we practiced, the whole responsibility of the factory passed into our hands.

We worked only during the day, except for the baking phase, which was also done at night. Baking bricks, fed with the set amount of fire, you have to pass from sector to sector, to complete the baking process. The furnace was an oval building divided into rooms. Teams of workers were constantly filling the rooms with unbaked bricks. After baking, other teams of workers took them out and so our process continued.

All sectors have quite a heavy workload, but this last phase was particularly difficult. The environment had a very high temperature, the air was full of dust and ash that came in from everywhere, and the rough red bricks in the fire had to be picked up by hand. We came out, covered in sweat that ran down our entire body, with dust in our mouths and nostrils, and our hands were numb. A truly terrible ordeal! It was in this place that I was assigned from the beginning and continued there for several months.

Except I must add that not everything was negative. During the previous years, I had worked for a long time immersed in water and as a result, I got a series of rheumatisms. I often felt severe pain, which sometimes prevented me from standing straight. However, this opposite “cure”, as punte we assigned between the ovens, is for me a wonderful healing touch. How can I not see in this an abduction of God? The one of Lumi found himself close to me in other ways too…!

My release…!

Agreement with Italy regarding the Peace Treaty; restoration of friendly and commercial ties; the decision that all Italians should be imprisoned or in labor and concentration camps should be prepared to be repatriated. I thought I was in a dream! It could be the first time, in ten or more years that I dreamed of release, because in my soul, the belief that I would never get out of there became more and more rooted.

My informant looked at me with a smile and sadness; He congratulated me and left, adding: “Your River is going, but we are staying in the mud.” I didn’t say a word, you thought that wisdom is never too much; I limited myself to thanking him, you hastened your steps on the way back. I went through the city almost running, without a word I was able to avoid the sight of some people who knew me and wanted to congratulate me, or, at least, to stop me and comment on the event.

But that day you were really busy, and then you know very well that some words are like some kind of seeds thrown by the wind that make long journeys to take root later, even on the top of a bell tower!

When I arrived in my sector, I found that the news had penetrated before me and the whole circle of internees was seething with curiosity. They surrounded me and expressed a thousand congratulations, but it was not difficult to see a shadow of sadness in their eyes.

They suffered from the thought of separation, and felt that they would lose even the little spiritual comfort that my service had brought them. I sought to de-dramatize the issue and gave them heart with faith that God would not abandon them. But in my soul, I was also longing and sad. I loved them with all my heart and they loved me the same.

This inverse love made me feel like a family member…! I cried too and I believe I’m not lying that if I had the chance, I would have given up on returning to my homeland, just to console that precious human mass.

In the camp, therefore, congratulations and tears; then, as Albanian custom dictates, evening visits, smoking cigarettes, coffee, a glass of brandy and, for women, candy. A real luxury! The wallet was empty, but the custom of the country in this case, it was filled with honor.

Then, late one evening, when we had already finished the meeting, we heard a knock on the door: with a very soft look, the sergeant, in charge of the sector, appeared, accompanied by three civilians. As if by instinct, we kept our mouths shut, a little worried, but we immediately breathed a sigh of relief when one of the three, in rather clumsy Italian, informed us that the “power” wanted our return to Italy to be successful, and therefore had given they ordered us to dress in new clothes.

I told the other two (a tailor and a shoemaker) to do their duty, i.e. to arrange for clothes, linen and shoes. Hello, they are gone. We looked into each other’s eyes, without saying anything; but that look told us a lot of things.

Meanwhile, the day of departure is approaching: it should be around the night of September 20. I don’t remember what means of transport they gave us. I only remember that all the internees were gathered around us and greeted us with tears in their eyes. We had given someone one thing, someone else: all we had. We took only the heart with us, even the one crushed by suffering…!

While the handkerchiefs were being waved, the car started on its way to Durrës. In the long back seat, four of us sat: me, Mario Verde, Neapolitan, Nino Tagliani, from Ferrara and Luigi Maucerri, from Sicily; in front, next to the driver, we saw a “guardian angel”, who during the three days we spent in Durrës, waiting for the ship, never left us, neither day nor night.

Extremely humane, he took us to the post office and sent telegrams to our families, invited us to coffee and drank brandy, took us for long walks around the city, talked about a thousand issues, and always noticed what we were saying. Wherever we entered, we were immediately surrounded by people who were interested in us, and who, of course, did not come there by chance.

After lunch on September 24, we headed to the harbor. I immediately saw a ship flying the Italian flag, and my heart began to pound. We found there waiting for us some other Italians whom I had never met. They were all professionals who had worked in Albania before. With the advent of communism, they had been detained for various reasons, under the guise of guilt, but, in reality, to continue practicing their profession, in the service of the state.

This meeting was also a great joy. Sometime later, a police officer arrived: he had a paper in his hand and, calling everyone by name, he led them up the stairs that led up to the ship. My turn came, I answered the call, and with my legs shaking a little, I climbed the stairs that took me to the ship. I got a message, which turned into a greeting “Bless you, Lord”. The captain of the ship who met us at the bottom of the stairs…! With a handshake, he encouraged me: “Sweetheart, Father, now I’m in command here”!

… It was September 24, the 50th anniversary of my birth…! Memorie.al